Breaking News! Huge Benefits For A Special Class of Friends | Adedunmade Onibokun

Election must not be a do or die affair. Sponsoring frivolous petitions to embarrass a candidate is indecent and dishonourable.

I will not say more for now.

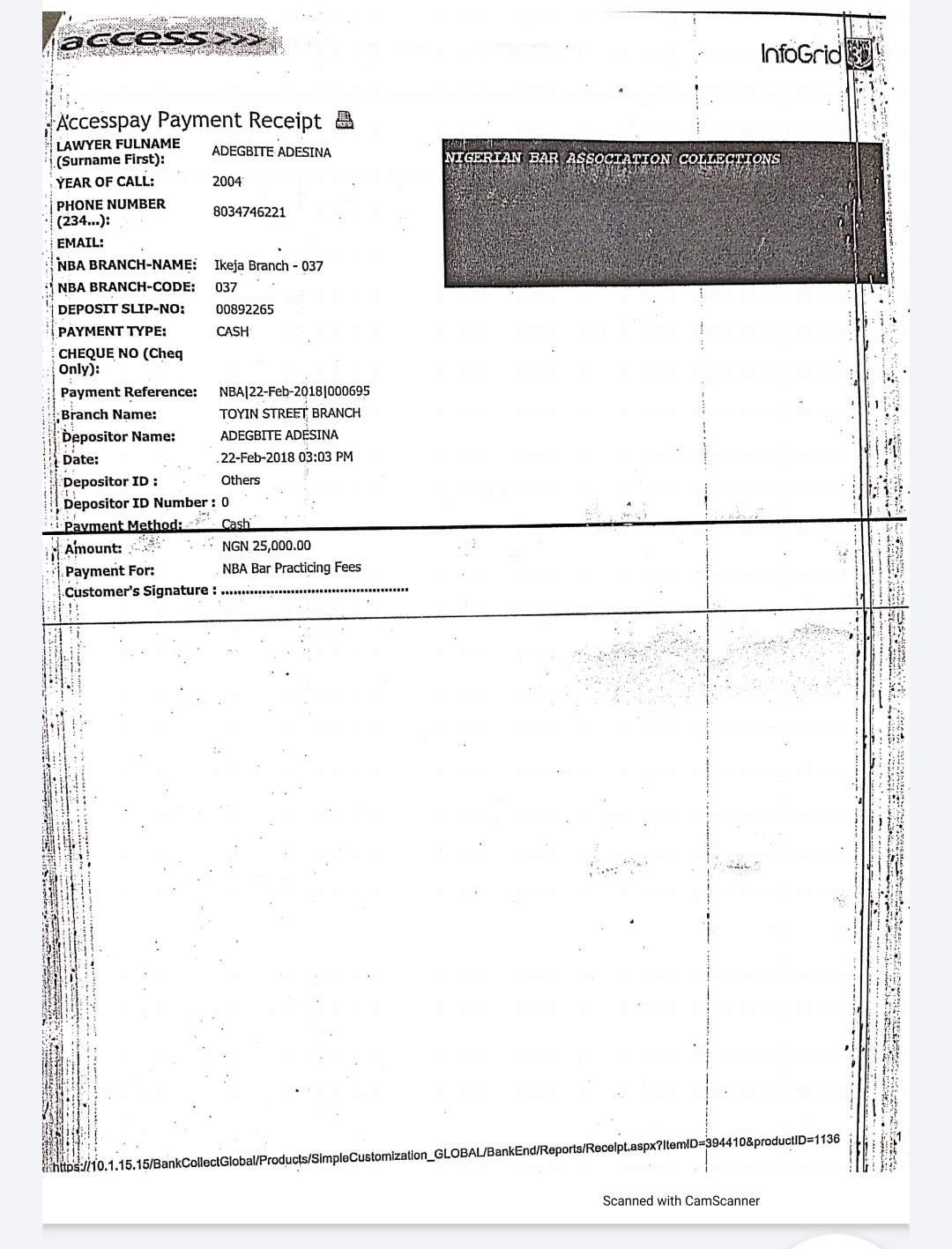

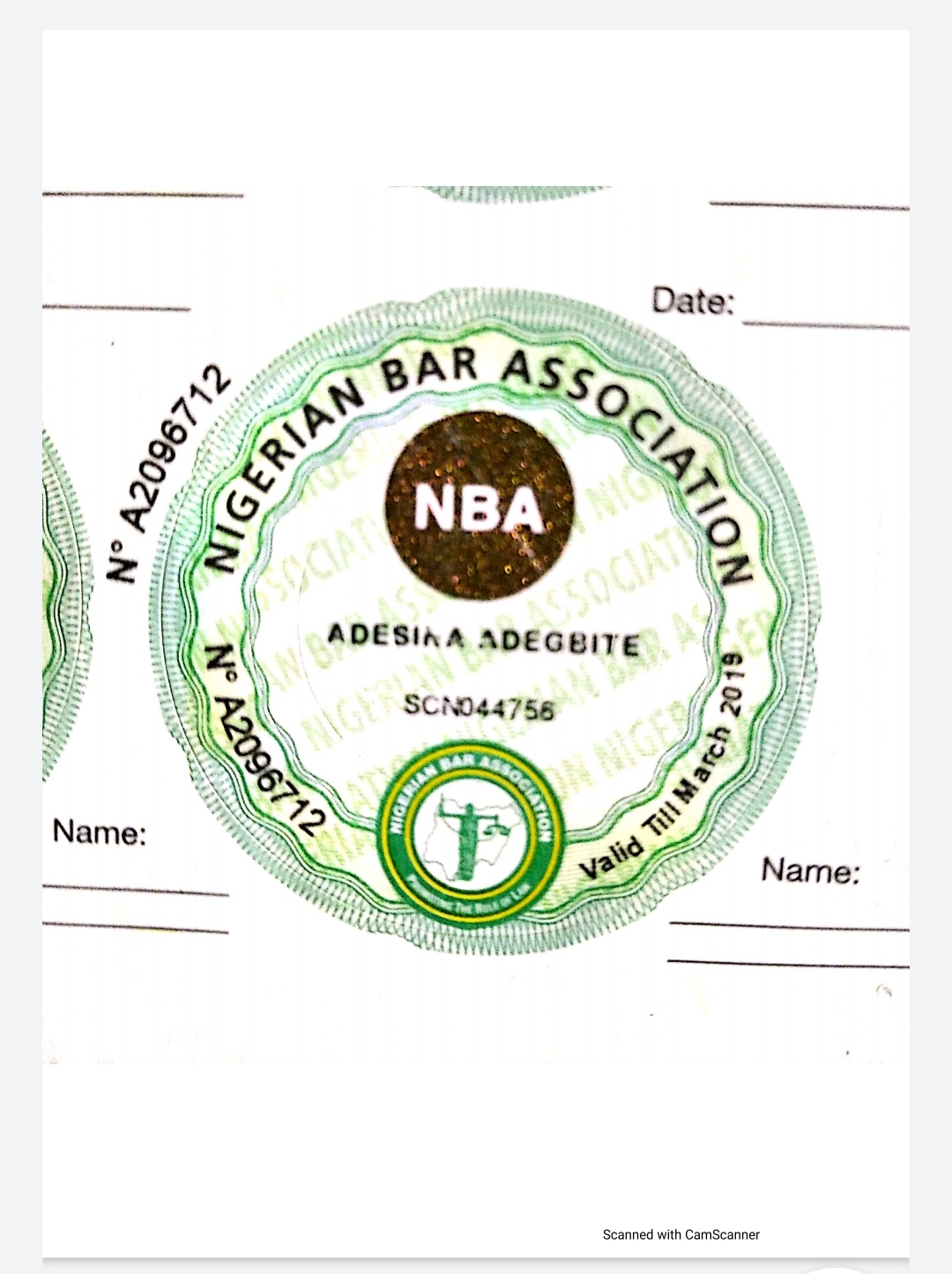

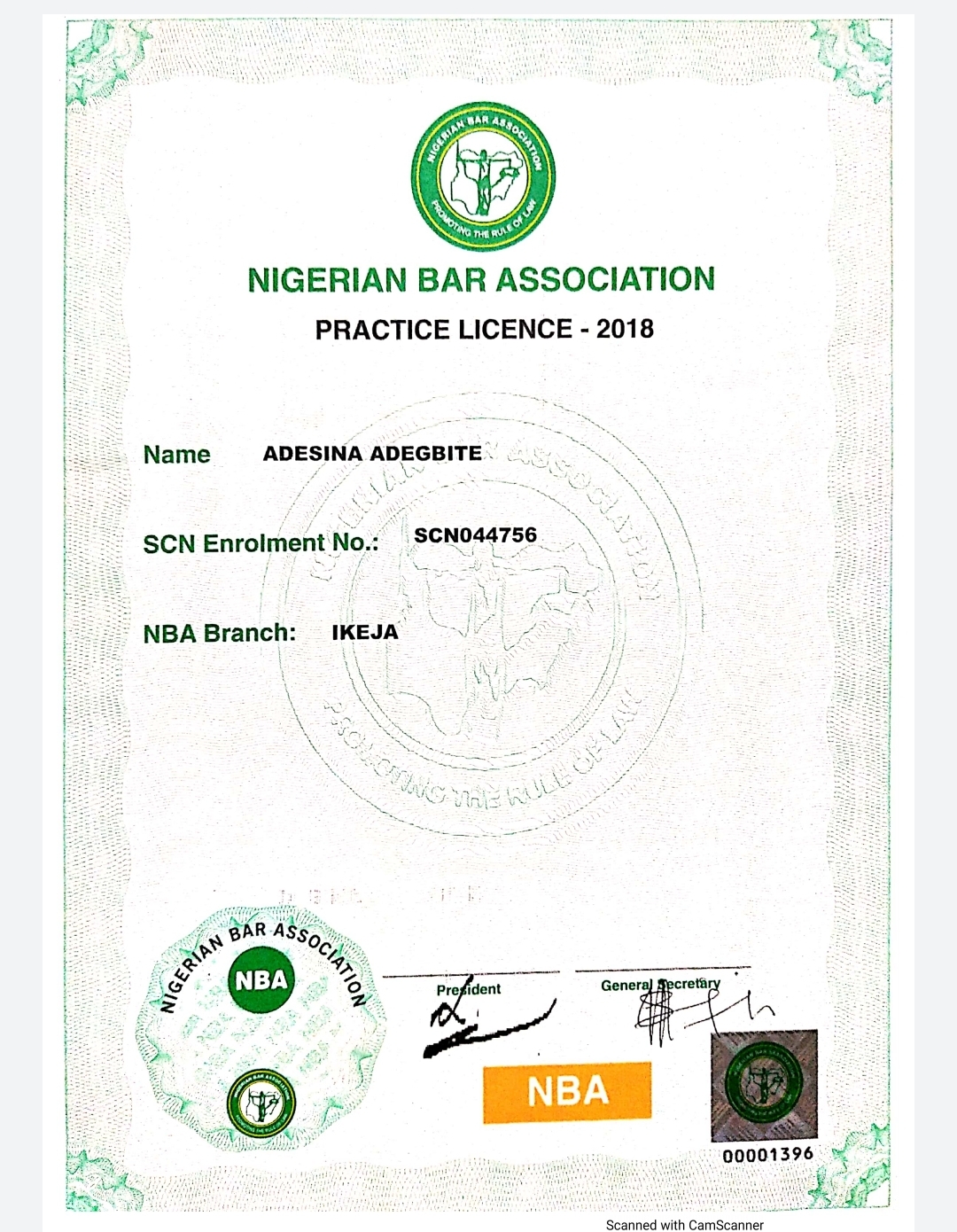

A. Adegbite Esq, FICMC

I KOLAWOLE PETERS DOPAMU have weighed all the options available and I must confess that all the contestants are men of great influence and character.

However, I have no hesitation in declaring my support for the PRIMUS INTER PARES amongst them. He is DEACON DELE ADESINA (SAN). DASAN

In declaring my support for DASAN I considered inter alia integrity, character, resourcefulness, experience in bar politics and conflict resolution prowess. I also considered relational proficiency of the candidates. I weighed each candidate on an imaginary scale before coming to the choice I made.

I find DASAN to be an effective administrator who has compassion for people. He is sympathetic to noble causes and exceptionally benevolent to needy souls.

I have known DASAN since the glorious days of Human Rights struggles as a pupil counsel in Gani Fawehinmi Chambers and I can only testify that he is a man with great vision and passion.

NBA is in dire need of a revolutionary. One who can bring the association to par with 21st century realities. DASAN exemplifies the essence of the yearnings of all men in wigs and gowns, old wigs and greenhorns!

I am persuaded that DASAN is THE MAN FOR THE JOB

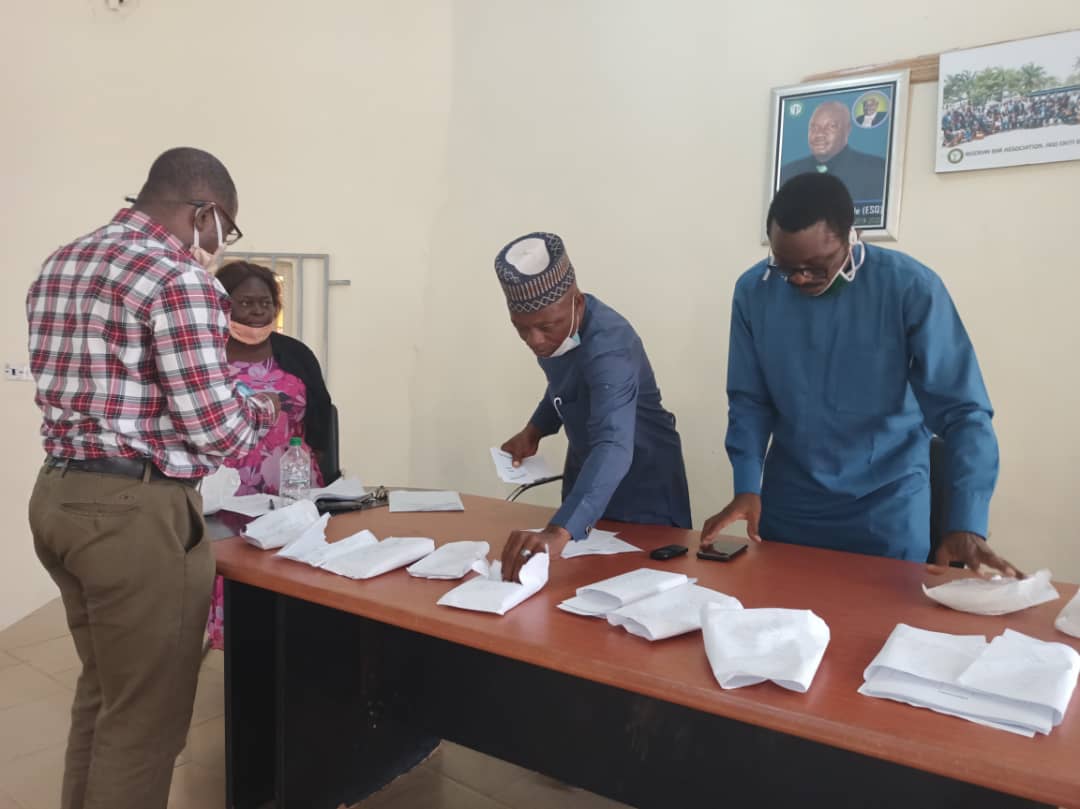

Adeyemi Adewumi 106 votes

C.O Omokhafe – 18 votes

L

O.T Obisesan – 4 votes

Alh. Abubakar Ajibade – 4 Votes

*V. Chairman*

Abigail Aladejare – 132 votes, Void 2

*Financiall Secretary*

Tomide Oshakile – 120 votes, 2votes against.

*Treasure*

Oluwaseyi Ebenezer – 126votes, 1votes against, void 3

*Publicity Secretary -*

Adetutu Oluwaseyi 127votes,Vote against 2, void 2

*Legal Adviser*

Akomolafe Oluwaseyi – 128votes, Void 5

*Assistant Secretary*

Bayode Kehinde – -93 votes

Femi Falade – 40 votes

*Secretary*

Akin Borode – 59votes

Oluwatobi Ogunbiyi -74votes

This

article attempts to settle the crisis between landlord and tenant. Part One of

the article explained everything about tenancy agreement and types of tenancy.

In this last part, we will focus on the rule guiding notice to quit, how to end

tenancy, procedure for recovery of premises and how to avoid the crisis between

landlord and tenant.

HOW

TO CALCULATE LENGTH OF NOTICE TO QUIT

Landlord

and Tenant are free to agree on the length of notice to quit; where there is no

agreement, Tenancy Law of the State where the property is located will apply.

The followings are default length of notice to quit provided by law.

1.

Yearly Tenancy: six months’ notice

2.

Half Yearly Tenancy: six months’ notice

3.

Quarterly Tenancy: three months’ notice

4.

Monthly Tenancy: a month’s notice

5.

Weekly Tenancy: a week’s notice

The

calculation of the length of notice to quit by the Court is very complex; a

month’s notice to quit, issued on 2nd November will expire on 31st December and

not 2nd December. Generally, notice to quit can be given at any time prior to

the date of expiration of the current tenancy. The length of the notice to quit

can be more than the one provided by the parties or the law but it must not be

shorter. In Abuja, notice to quit must terminate at the eve of the anniversary

of the current term (i.e. a day before expiration of tenancy). While in Lagos,

notice to quit is valid once it is stated to terminate on or after the

expiration of tenancy. In Nigeria, all states have different law on tenancy;

the provisions are the same with minor changes.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

These

are some of the questions I received after the publication of “Tenancy Crisis

Part One”.

QUESTION

ONE:

My

landlord threatens to use police to evict me because I owed him six months’

rent. Please help me.

ANSWER:

The Landlord cannot force you out of the premises with the help of Police

because doing so will amount to trespass. The law protects you and gives you

the right to sue your landlord for damages whenever the landlord enters your

apartment without your consent or used force to evict you. The right thing for

the landlord to do is to follow due process of law by approaching the Court.

QUESTION

TWO:

My

tenant refused to pay rent for three years now. I do not want him to occupy my

property again. I want to involve the Police because I tried every peaceful

method. What do you think I should do?

ANSWER:

Tenancy relationship is not regulated by criminal law, it is wrong to report a

tenancy matter to the Police. However, the Police can only be invited when

there is a fight, burglary, etc. The duty of the police is limited to the

criminal matters arising from tenancy relationships. Thus, reporting the matter

to the Police will amount to waste of time and resources because the Police

will surely refer the matter to the Court. The right thing to do is to read the

tenancy agreement, in order to check the procedure for eviction. Where the

procedure for eviction is not stated in the agreement, peruse the law of the

state where the property situates for direction. Usually, if a tenant owes

arrears of rent for more than one year, it is good for the landlord to issue

seven days’ notice of owner’s intention to apply to Court to recover premises,

and then proceed to file action for repossession in Court after the expiration

of the seven days.

HOW TO END TENANCY

There

are several ways by which tenancy can be determined. The choice of which one to

take is crucial because choosing a wrong mode can lead to conflict.

Surrender:

This

is when the Tenant gives up possession voluntarily before the expiration of the

agreed period. It may be express or implied by conduct. To be effective, the

Landlord must indicate acceptance.

Forfeiture:

This

is when the Landlord re-enter the premises or apply to court to terminate

tenancy on the occurrence of certain event. This can only occur in fixed

tenancy and must be stated in the tenancy agreement.

Merger:

Here

the Landlord surrenders his interest to the Tenant. This is when a Tenant

purchases the property or acquires a superior estate owned by the Landlord. It

is the opposite of surrender.

Rescission:

This

is where the law permits one of the parties to apply to court to terminate

tenancy when there is an element of fraud in the tenancy relationship.

Force

Majeure:

Where

there is an occurrence of event without the fault of either party, tenancy will

come to an end. For example, destruction of property by fire or flood.

Effluxion

of time:

This

is where tenancy relationship comes to an end upon expiration of the agreed

period. Service of notice is not necessary but the tenancy agreement may

contain option to renew and service of notice to quit. The law prohibits

forceful eviction. Thus, due process of law must be followed.

Termination

by Operation of Law:

This

is when the law permits recovery without issuance of notice to quit. Once a

monthly Tenant is in arrears of rent for three months, the Landlord can issue

seven days’ notice of owner’s intention to apply to court to recover

possession. The tenant is not entitled to notice to quit. Also, the tenant is

not entitled to notice to quit in fixed tenancy (as discussed above) and a half

yearly tenant in arrears of one year is not entitled to notice to quit.

PROCEDURE

FOR THE RECOVERY OF PROPERTY

a.

The Landlord should issue letter of authority to a Lawyer,

b.

The lawyer will issue notice to quit (where necessary). If the Tenant fails to

deliver possession at the expiration of notice to quit,

c.

The lawyer will issue seven days’ notice of owner’s intention to apply to court

to recover possession. If the Tenant neglect to vacate the premises at the end

of seven days,

d.

The lawyer will approach the appropriate court (Magistrate Court or High Court;

depending on the rental value of the property),

e.

Court will issue summons and commence trial,

f.

The Court will deliver judgment (usually extending the stay of the tenant for

certain period or order the tenant to vacate the property immediately and award

necessary costs). Where the tenant is ordered to pay arrears of rent and such

Tenant has no money, the court will attach valuable personal property of the

Tenant and auction it to pay the Landlord.

HOW

TO AVOID TENANCY CRISIS

The

Tenant should deliver possession once notice to quit has been served. Where the

Tenant neglects to deliver possession after the end of tenancy and subsequent

issuance of statutory notices; the Landlord should not forcibly evict the

Tenant because doing so may lead to avoidable legal battle and financial waste.

The legal option for the Landlord is to take action in court and demand for

repossession, costs and arrears of rent/damages.

Read Part of the article via:

1.

https://thenigerialawyer.com/tenancy-crisis-part-one-nature-of-tenancy-covenants/

2. http://insidearewa.com.ng/tenancy-crisis-part-one-nature-of-tenancy-covenants/

5. https://www.legalnaija.com/2020/06/tenancy-crisis-part-one-nature-of_6.html?m=1

Other

articles by the Author:

1.DIVORCE:

https://thenigerialawyer.com/grounds-for-divorce-a-legal-digest/

2.

Life after Law School. https://www.legalnaija.com/2020/05/life-after-law-school-setting-up-right.html?m=1

Contact

the Author:

Twitter: @OkpiBernard

Email: okpibernardadaafu@gmail.com

Phone: +2349032116272

OKPI BERNARD ADAAFU (OBA) ESQ (LL.B, B.L, ACIArb, MCMC) is an Associate at KANU

G. AGABI, SAN (CON) & ASSOCIATES, Abuja, Nigeria.

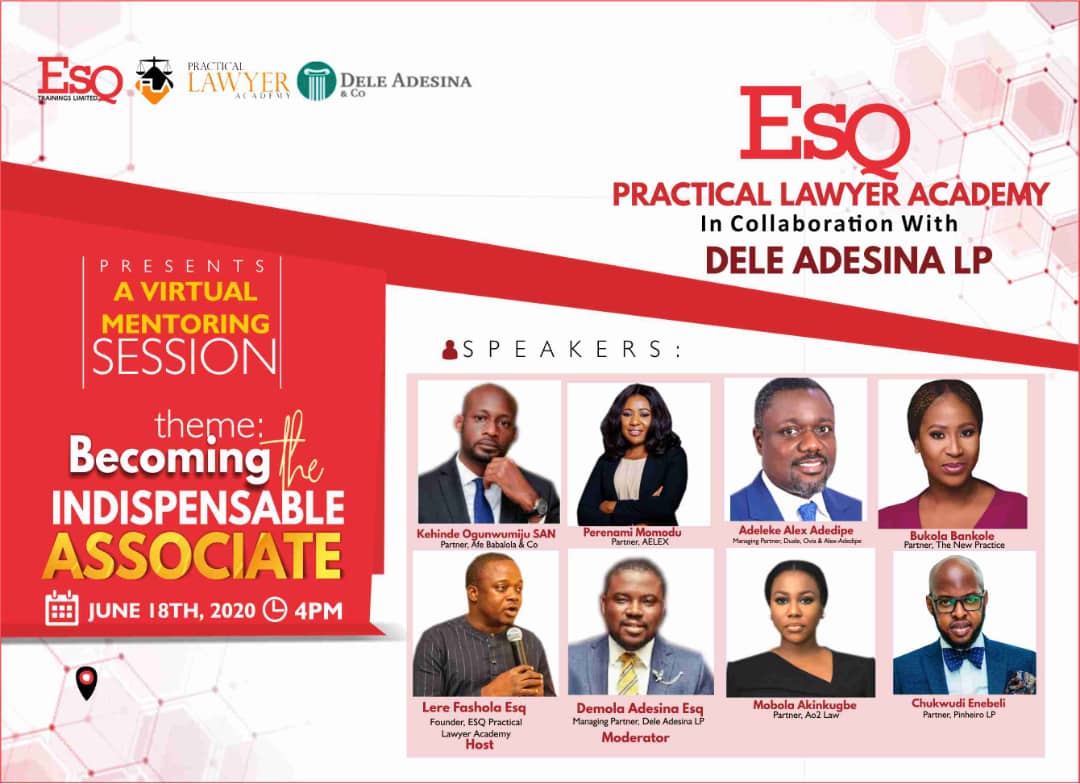

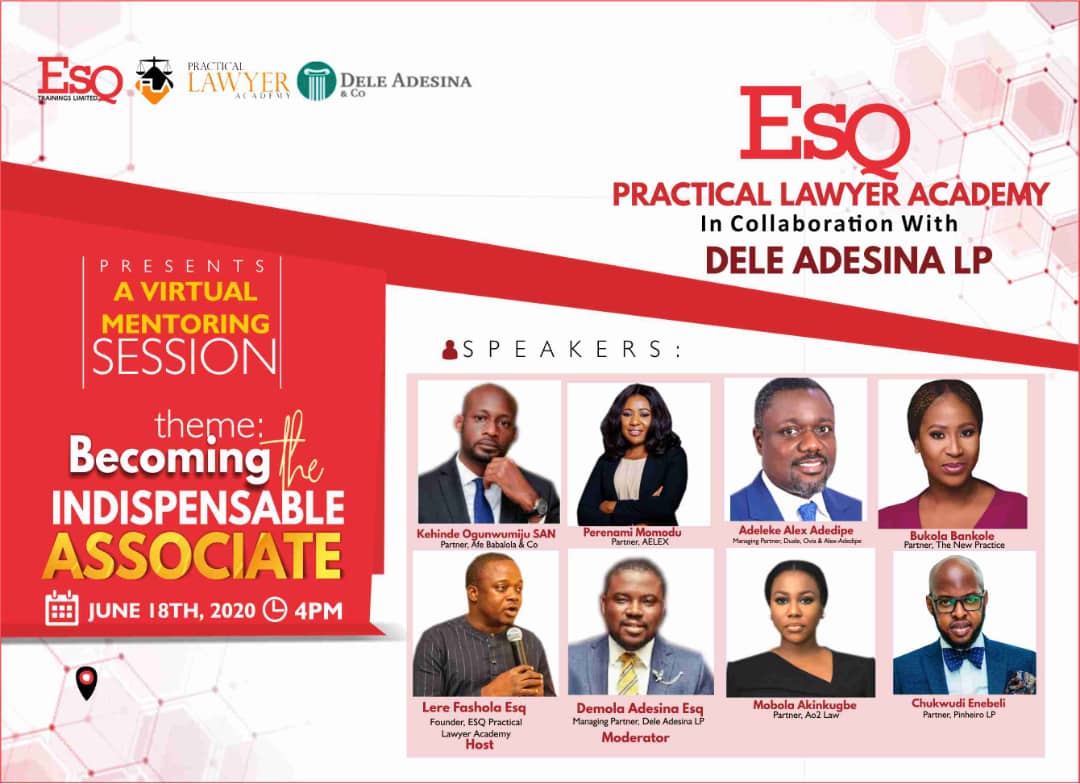

Time: 4pm

Registration: https://bit.ly/ESQWebinar

https://bit.ly/ESQWebinar

MAKE IT A DATE

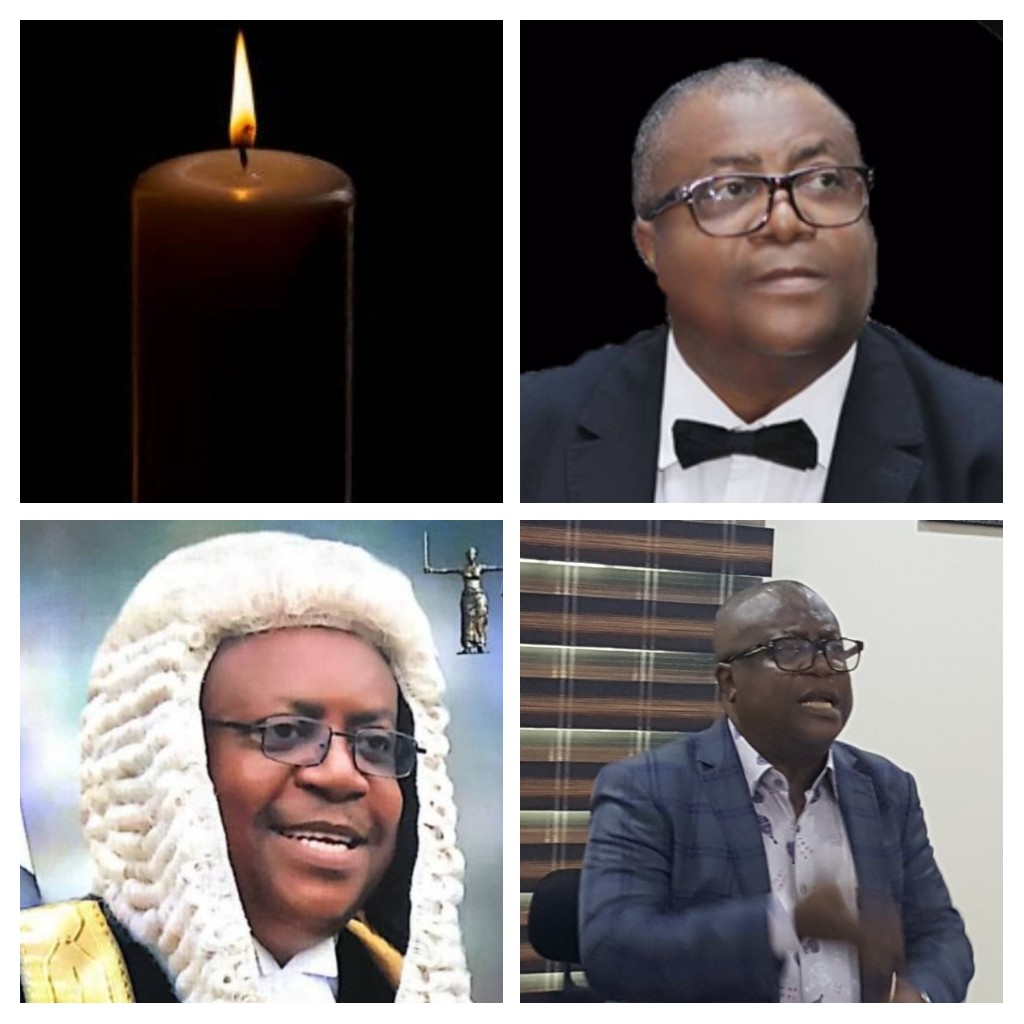

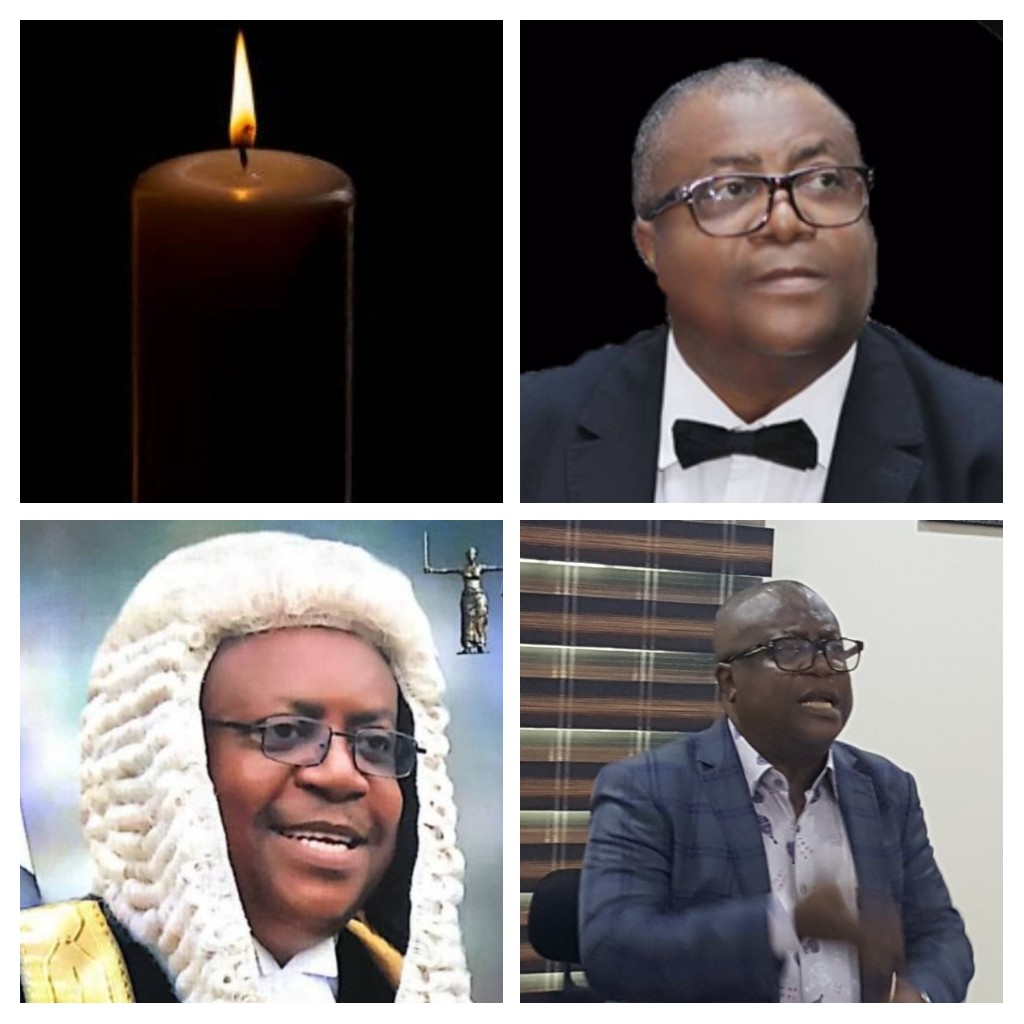

I have received barrage of phone calls, all of which have conveyed the rude and shocking news to me that Granville Isetima Abibo SAN died this morning. My immediate reaction was that of total disbelief because I did not in any way see it coming. The confirmation of the news shattered and devastated me. Then pain set in. This is one death too many. Death, you have created a big vacuum that would be too hard to fill. Why? Why Granville Abibo?

I have had a sustained relationship with Granville for over Twenty (20) years. Granville was an extraordinary friend. His commitment to relationship is unsurpassable. He valued, nurtured, and sustained our relationship continually and continuously. I am yet unable to say *”Good Night”* to Granville. Granville was until his death one of our Generals in Team DASAN

To all members of Team DASAN Nationwide, I hereby direct that we suspend immediately further consultations and engagements on the ongoing Electoral process of the NBA in honour and respect of the person of our great Friend for the next Twenty-Four (24) hours. My heartfelt condolences to his wife; children; the staff of Granville Abibo & Co.; members of Nigerian Bar Association, Port-Harcourt Branch; the Body of Senior Advocates of Nigeria; and members of Team DASAN Nationwide.

I pray that God will grant us all the fortitude to bear this irreparable loss.

*Dele Adesina SAN, FCI Arb.*

Hon. Justice Peter Obiorah in his ruling delivered on 2nd June, 2020, noted that this practice of raising preliminary objections to suits filed against the defendant company has gained propensity and stated

that the “only issue for determination is whether this suit is incompetent by reason of the plaintiffs’ failure to first initiate and exhaust the procedure for complaint established under the National Electricity Regulatory Commission’s Customer Complaints Handling Standards and Procedures 2006.”

Section 3(5) of the Regulation which the EEDC relied on for the preliminary objection reads –

*All complaints must be lodged firstly, in writing, with the Customer Complaints Unit of the Distribution Licensee.*

The court further construed Section 3(8) on method of treating the complaint by the Customer Complaints Unit; further complaint to the Forum constituted under Section 4 of the Regulation and appeal to the National Electricity Regulatory Commission against the background of Section 13 which states that:

*”Noting contained in these Regulations shall affect the rights and privileges of the customer under any other law for the time being in force, including those under the Consumer Protection Council Act No. 66 of 1992.*”

The learned trial Judge, on the vexed issue of a condition precedent, considered the cases of *Prince J. S. Atolagbe & Ors. v. Alhaji Awuni & Ors (1997) LPELR-593(SC) at 19* and relied on the decision in *Drexel Energy and Natural Resources Ltd v. Trans International (2008) LPELR-962(SC)* where the Supreme Court, per Aderemi, JSC held that “The question may be asked: What is a “CONDITION PRECEDENT?” The answer is not farfetched; When everything has happened which, prima facie, will vest in a party a certain right of action, such as the writ of summons in the instant case which contains materials of the complaint of the plaintiff/appellants and yet in this particular case there is something further to be done, or something more must happen before he is entitled to sue either by reason of provision of some statute or because the parties have expressly so agreed that something more is called “CONDITION PRECEDENT.”

Going further, the trial court stated that “a very popular form of a condition precedent is found in several legislations that prescribe the issuance and service of pre-action notice on a party before such party can be sued in court. See Section 11(2) of the Nigerian National Petroleum Act interpreted in Captain E.C.C. Amadi v. NNPC (2000) LPELR-445(SC) and Section 97(2) of the Nigerian Ports Authority Act interpreted in Umukoro v. N.P.A. (1997) 4 NWLR (Pt. 502) 656.”

His Lordship also stated that parties may expressly agree on a condition precedent and such agreements are commonly found in arbitration clauses in agreement which in unmistaken terms state that resort to arbitration must be had first before a right of action can accrue. He held that in “these situations, the legislation or agreement state so in clear and unambiguous terms. It is not a matter for conjecture or speculation. In the instant case, the Regulations did not make any allusion to a court action or that an aggrieved customer cannot approach the court until he has made the complaint to the Customer Complaints Unit. It is wrong for a person to read into a law or Regulations what is not expressly contained therein.”

Continuing the Judge held that *”In my considered opinion, what the Regulations prescribed as a channel of complaint can be an alternative to a court action. I think it depends on the customer to take advantage of that internal mechanism for resolution of complaints or he may head straight to the courts. There is absolutely nothing in the wordings of the National Electricity Regulatory Commission’s Customer Complaints Handling Standards and Procedures 2006 from where one can draw the inference that the jurisdiction of the court is ousted until and unless there is compliance with the submission of the complaint to the Customer Complaints Unit of the defendant. In fact, if there is any doubt on whether a customer can approach the court without first reporting to the Customer Complaints Unit, then Section 13 of the Regulations provided the answer or tonic to clear the doubt. In very bold and simple language it states that nothing in the Regulations “shall affect the rights and privileges of the customer under any other law for the time being in force.” In effect, the Regulation is made subject to other laws.”*

Concluding, the High Court held that “a customer who decides to go straight to the court to ventilate his grievances against the defendant cannot be shut out by the court and compelled to first explore the internal mechanism of the defendant. The result is that I find no merit in the preliminary objection.

It is my fervent opinion that the observance and compliance with the National Electricity Regulatory Commission’s Customer Complaints Handling Standards and Procedures 2006, is not a condition precedent to the institution of a civil action against the defendant by any aggrieved customer, like the plaintiffs in the instant case. Accordingly, I hereby dismiss the objection for lack of merit.”

Sabastine Anyia, Esq.