“There can be no keener revelation of a

society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.”

The role of children in any

society cannot be over-emphasized. Every culture in its own peculiar way, with

or without laws, by default, protects the young. The fact that the present

young population are going to be responsible for running society in the next

twenty to forty years, means that much attention should be paid to children’s

development. As expected, each society’s culture determines how its children

are treated. What might be acceptable to one society, might be completely

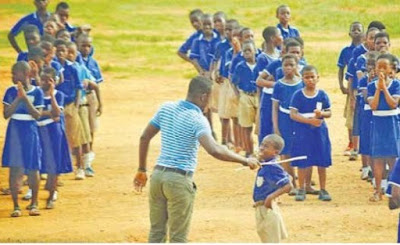

abhorrent to another. Two decades ago, flogging children in primary and

secondary schools in Nigeria was widely acceptable.

This was irrespective of

whether the school was public, private or a missionary school. Today, the

narrative is different. Even without the prompting of the government,

most private schools in Nigeria have already banned all forms of flogging or

hitting by teachers or other staff. In

response, some teachers have lamented that the

absence of corporal punishment encourages pupils to be rude to them. Last year,

the Minister of State for Education, Chukwuemeka Nwajiuba, was reported to have

said that the federal government would

no longer tolerate bullying in

schools, but he was not referring to corporal punishment.[1]

Furthermore, the Spokesperson of the Education Ministry, Ben Goong, emphasized

that the government did not ban corporal punishment.[2]

In Nigeria, corporal

punishments are widely acceptable to the extent that it is unthinkable that a

child will be allowed to grow without physical discipline. While the benefits

are often listed, little is known about the psychological effects on some

children and the healing process involved. Consequently, the culture of

disciplining children physically in the home transcends from the home to the

school and other public spaces. In some communities, an adult may discipline a

child for inappropriate behaviour in public and upon returning the child to the

parents with a report of what transpired, receive a warm welcome. It takes a

community to raise a child. Notably, Article

295 of the Criminal Code (South), article 55 of the Penal Code (North) and the

Shari’a penal codes in the Northern states confirm the right of parents to use

force to “correct” their children. Yet as we consider what is culturally

acceptable in our geographical space, it is important to take note that fortunately, or unfortunately, the world is

quickly shrinking into one global village with national leaders including

Nigerian leaders, signing treaties which will affect the lives of the citizens unbeknownst

to them. For this reason, the topic of disciplining young children in Nigerian

schools cannot be discussed without a consideration of the larger picture- global

practice. It is important to set out however that the consideration of what is

obtainable in other societies is not with a view to compare. The role of

children in the Nigerian society is so important that their affairs cannot be

decided on without recourse to the essence of who we are as a nation.

Currently, Europe and many

parts of South America practice prohibition of corporal punishment in all

settings. Russia, North America and Canada among others have achieved prohibition

in some settings while Nigeria, Botswana, Saudi Arabia and some others have not

fully prohibited corporal punishment in any setting.[3] Notably,

every continent at some point in their ancient history allowed corporal

punishment. In the UK for instance, in the last century, the issue of corporal

punishment in schools was often met with a perceived incompatibility with

Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

While the Article prohibits torture and degrading treatment, in cases like Tyrer v

UK[4] and Costello-Roberts

v UK[5] the

issue of corporal punishment was considered in light of the Article. In

Costello-Roberts’ case, the court found that there was no infringement of

Article 3 in slippering a seven-year old child, but in Tyrer’s case, the court held

that the birching of a 15-year old boy was a violation of Article 3. In a

dissenting judgment in Tyrer’s case, Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice noted that Article

3 was not intended as a vehicle for penal reform. The European Convention was

post World War II and was concerned with the torture and ill-treatment

perpetuated by the Nazis and not necessarily corporal punishment.[6] However,

the creation of some fundamental rights had implications not intended by the

drafters. As chairperson of the drafting committee of the Universal

Declaration, Eleanor Roosevelt expressed concern that provisions outlawing

torture and ill-treatment might prohibit the practice of other things such as

compulsory vaccination.[7] These

concerns though voiced in a different context must lead us to ask questions such

as what the unintended effects will be if teachers are prohibited from

administering corporal punishment across all schools and all ages? This is in

view of the fact that Nigeria is a culturally different clime from the Western

World and cannot be seen to adopt Western procedures if not in the best

interest of the child and the society. However, while these questions persist,

the government continues to ratify international treaties and make commitments

which sooner or later, might completely wipe out corporal punishment.

In 1991, Nigeria ratified

the Convention on the Right of the Child (CRC). With the exception of some

northern states, many states have domesticated the CRC as state laws. The CRC

in Article 28(2) provides as follows:

“States Parties shall take all appropriate

measures to ensure that school discipline is administered in a manner

consistent with the child’s human dignity and in conformity with the present

Convention.”

It is also notable that the

Nigerian government is committed under the Sustainable Development Agenda

2030 and Africa’s Agenda for Children 2040. This year, the Global Initiative together

with Amnesty International Nigeria, is working on a project to bring law reform

on corporal punishment to the forefront of the Nigerian Government’s agenda. According

to the UN, corporal punishment is ‘any punishment in which physical

force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however

light. It involves hitting (‘smacking’, ‘slapping’, ‘spanking’) children, with

the hand or with an implement – whip, stick, belt, shoe, wooden spoon, etc. It

can also involve, for example, kicking, shaking or throwing children,

scratching, pinching, burning, scalding or forced ingestion’.[8] In a 2019 report of the Global Initiative to End

All Corporal Punishment for Children in Nigeria, they noted that prohibition is

still to be achieved in the home, alternative care settings, day care, schools,

penal institutions and as a sentence for crime. According to them, these

provisions should be repealed, and prohibition enacted of all corporal

punishment by parents and others with parental authority.[9] If this

is achieved, corporal punishments will not only be prohibited in schools but

also in the home.

But as the international

community puts pressure on Nigeria to walk away from all forms of corporal

punishment and many private schools are abandoning it for lighter modes of

discipline, it is important to assess what corporal punishment in Nigerian

schools have done for us as a nation both positive and negative. Amidst reports

of many children (now adults) who appeared to attain to a well-rounded

development as a result of being flogged in schools, are reports of adults who

have scars of being victims of violent abuse at the hands of teachers. Evidence

on the topic shows support for both sides. Does corporal punishment have a

place in our society? Has it helped our

society? Should it be retained or banned in schools? Have children been made to

endure violence and abuse at the hands of teachers? Do the benefits if any, outweigh

the harm?

[1] Azeezat Adedigba, “Teachers, parents

react as Nigerian schools gradually abandon corporal punishment” https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/378623-teachers-parents-react-as-nigerian-schools-gradually-abandon-corporal-punishment.html assessed 6 June 2020.

[2]

Ibid.

[3]

Summary of necessary legal reform to achieve full prohibition https://endcorporalpunishment.org/reports-on-every-state-and-territory/nigeria/#:~:text=Corporal%20punishment%20is%20lawful%20in%20schools%20under%20article%20295(4,cases%20correction%20ought%20to%20be assessed 6 June 2020.

[4]

[1978] ECHR 2

[5]

[1993] ECHR 16

[6]

Barry Phillips The Case for Corporal Punishment in the UK. Beaten into Submission

(1994) 43 The International and Comparative Law Quarterly No. 1 153.

[7]

Barry Phillips (n3) 162.

[8]

(UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2006: 4)

[9] Summary of necessary legal reform to achieve full prohibition

(n3).

Photo Credit – www.allafrica.com