by Legalnaija | Feb 14, 2026 | Blawg, Uncategorized

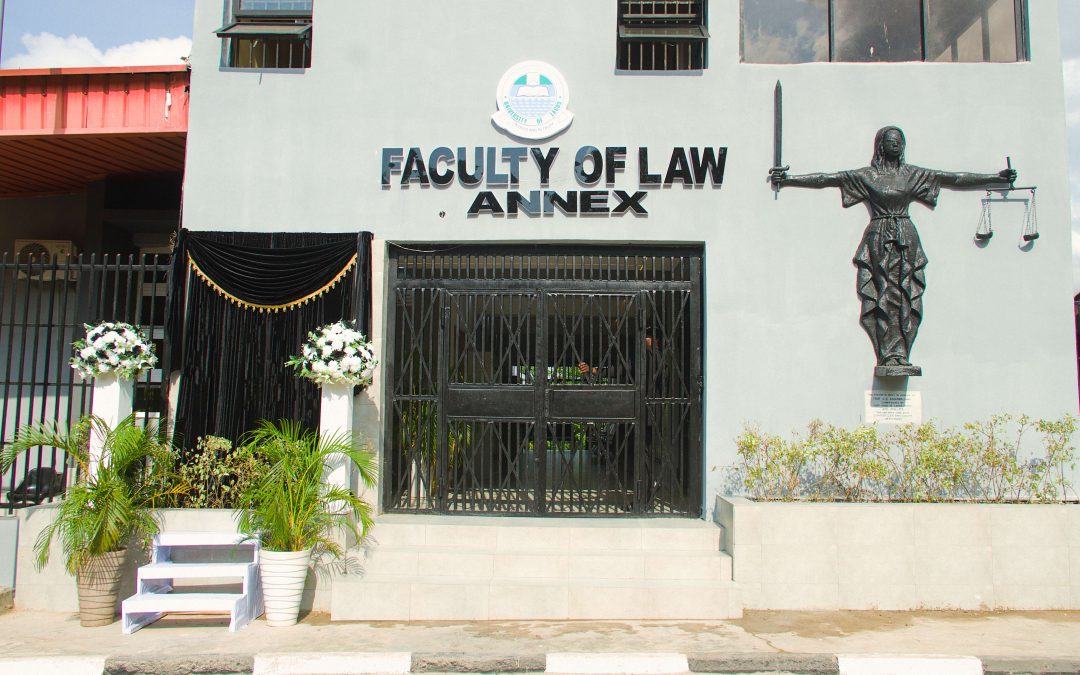

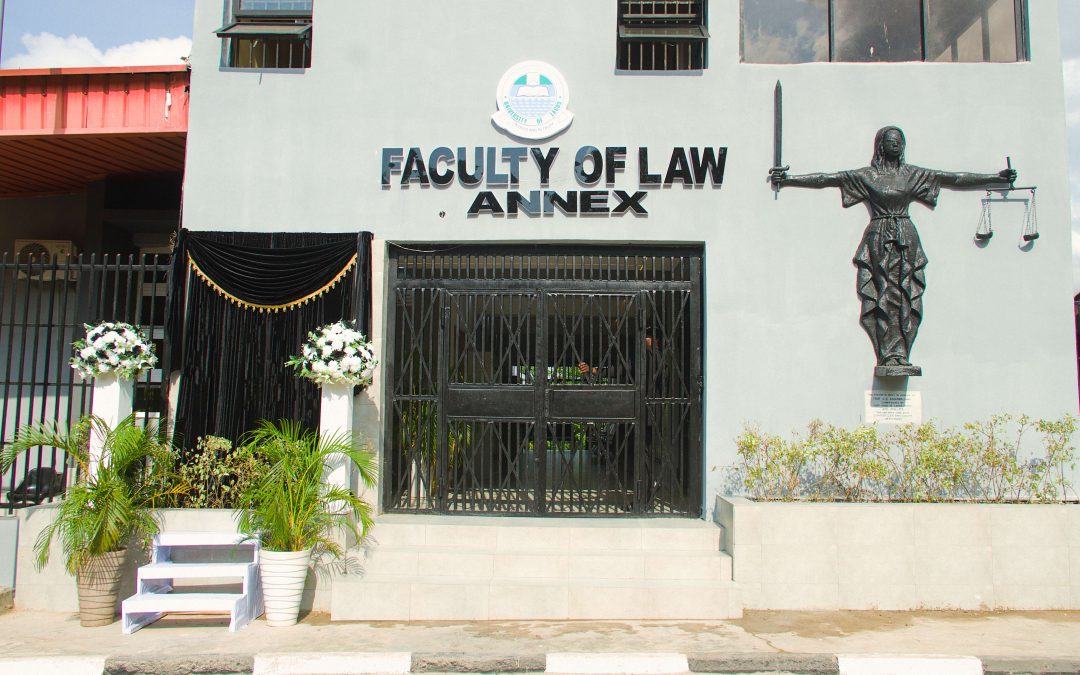

The Faculty of Law, University of Lagos, has unveiled a newly renovated Law Annex Lecture Hall in honour of His Excellency, Justice George A. Oguntade, a retired Justice of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, in a ceremony that brought together eminent jurists, academics, legal practitioners, and government officials.

The event, held at the university’s Faculty of Law, highlighted the institution’s commitment to strengthening legal education and preserving the legacy of distinguished figures who have shaped Nigeria’s justice system. Leading the ceremony was the Dean of the Faculty of Law, Prof. Abiola Sanni, who described the renovation project as both a symbolic and practical investment in the future of legal scholarship.

Among the dignitaries present were the Chief Judge of Lagos State, Justice Kazeem Olanrewaju Alogba, the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Development Services), Prof. Foluso Ebun Lesi, who represented the Vice-Chancellor of the university, and Senior Advocates of Nigeria, Chief George M. Oguntade; Mrs Folashade Alli, Prof Lanre Fagbohun, Chief Bolaji Ayorinde and Prof Dayo Amokaye. Their presence underscored the significance of the occasion within both academic and judicial circles.

Speaking at the unveiling, speakers reflected on the remarkable contributions of Justice Oguntade to the Nigerian judiciary, legal jurisprudence, and mentorship of younger legal minds. The renovated facility, they noted, is designed to provide a more conducive learning environment for law students and to further enhance teaching and research activities within the faculty.

The ceremony also attracted senior legal scholars and public office holders, including Hon. Dayo Bush-Alebiosu, Commissioner for Waterfront Infrastructure Development in Lagos State, who is also one of the donors, Prof. Taiwo Osipitan SAN, and legal practitioner Mr. Olugbenga Ajala, Esq., who as the covener of the initiative spoke on behalf of the donors and whose attendance reinforced the strong collaboration between the legal profession and academic institutions in advancing legal education.

In his remarks, Justice Oguntade expressed appreciation for the honour bestowed on him, describing it as a profound recognition of his lifelong commitment to justice, integrity, and service. He urged students of law to pursue excellence and uphold ethical standards in their future careers, noting that the strength of the legal system depends largely on the character and diligence of those who serve within it.

The unveiling of the renovated Law Annex Lecture Hall marks another milestone in the Faculty of Law’s ongoing efforts to modernize its infrastructure and improve learning facilities. Stakeholders at the event emphasized that such initiatives not only preserve institutional heritage but also inspire the next generation of legal practitioners.

The ceremony concluded with a guided tour of the upgraded lecture hall and a renewed call for continued partnerships that will strengthen legal education and uphold the values of justice and rule of law in Nigeria.

by Legalnaija | Feb 10, 2026 | Blawg

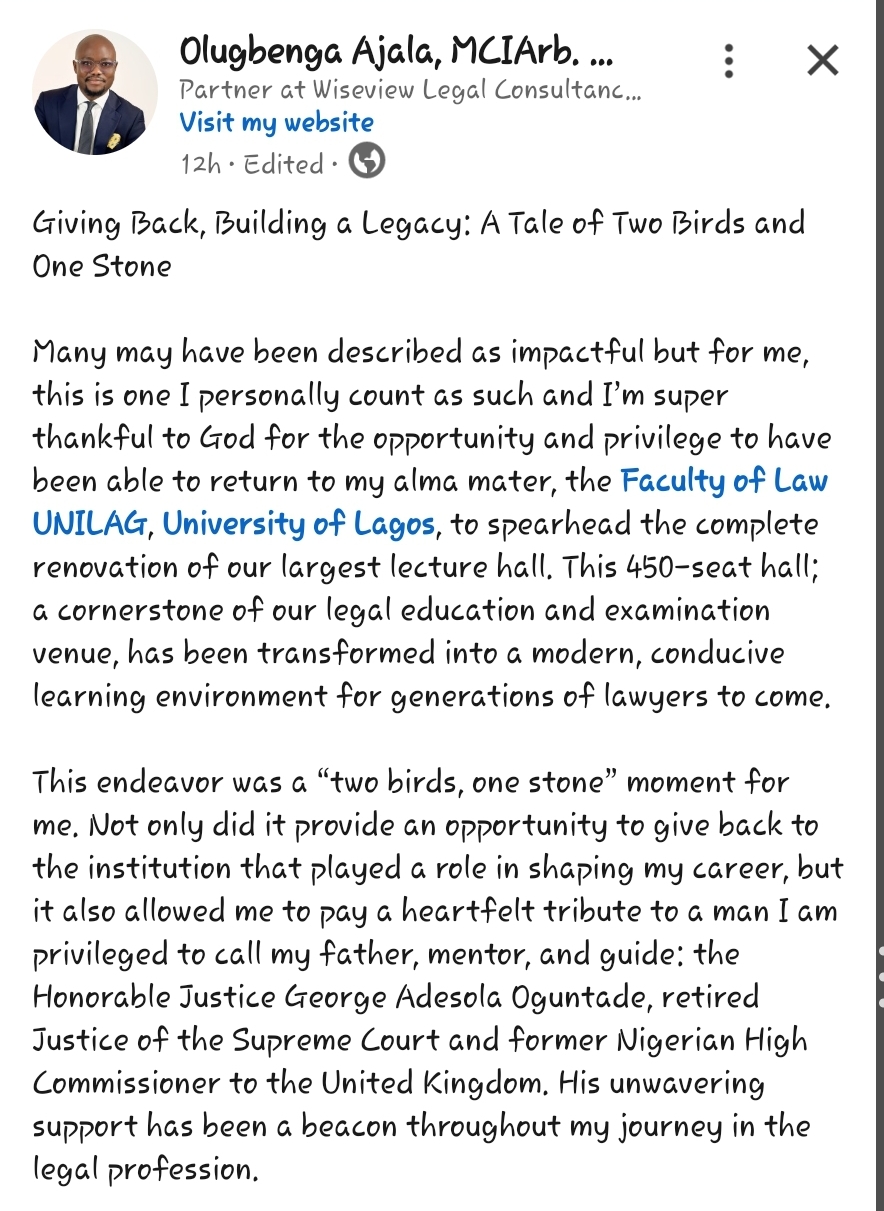

Young lawyers across Nigeria can now register for the landmark initiative by Senior Advocate of Nigeria and former Chairman of the NBA Lagos Branch, Yemi Akangbe, SAN, which provides complimentary access to the NWLR online platform for 25,000 practitioners between 0–7 years at the Bar on a first-come, first-served basis.

The registration portal went live today, marking the commencement of what is set to be one of the most significant interventions in legal professional development in recent years. Eligible lawyers can now register at https://tinyurl.com/YemiNWLR to access the platform, which ordinarily costs N50,000 per user annually. With only 25,000 slots available, young lawyers are advised to register promptly to secure their access.

The initiative, procured by Akangbe in partnership with Nigerian Law Publications Ltd, publishers of the Nigerian Weekly Law Reports (NWLR), is designed to remove financial barriers that prevent young practitioners from accessing essential legal research tools. The NWLR platform, recognised as Nigeria’s foremost law reporting service, houses decades of authoritative case law and judicial precedents critical to effective legal practice.

The programme reflects the philosophy of the late Chief Gani Fawehinmi, SAN, who championed the democratisation of legal knowledge throughout his career. Fawehinmi believed that excellence in legal practice could not flourish where access to knowledge was restricted by economic barriers, a conviction that Akangbe has now translated into concrete action for the digital age.

With thousands of new lawyers called to the Bar annually, many find themselves unable to afford comprehensive legal databases despite their centrality to quality legal work. By personally bearing the full cost of subscriptions for 25,000 young lawyers, Akangbe has demonstrated extraordinary commitment to the professional development of the next generation and the future of Nigeria’s legal system.

Place Valentine Orders On Legalnaija.com/store

The NWLR online platform provides access to reported judgments of Nigeria’s superior courts, enabling practitioners to study judicial reasoning, track the evolution of legal principles, and deliver well-researched advice and advocacy for their clients. For young lawyers in the crucial first seven years of practice, this access can prove transformative in establishing solid foundations for their careers.

The registration process has been designed to be straightforward and inclusive, ensuring that all eligible practitioners within the 0–7 year post-call bracket can benefit. However, with the initiative operating on a first-come, first-served basis, young lawyers are strongly encouraged to register immediately at https://tinyurl.com/YemiNWLR to secure their spot among the 25,000 beneficiaries.

The initiative has been met with overwhelming enthusiasm from young practitioners across the country, with many describing it as a timely intervention that will significantly enhance their capacity to conduct thorough legal research and serve their clients effectively.

As Nigeria’s legal profession continues to expand, Akangbe’s substantial personal investment sets a new benchmark for leadership and demonstrates what is possible when senior practitioners translate their concern for the future of the Bar into concrete, transformative action.

Eligible lawyers are advised to visit https://tinyurl.com/YemiNWLR immediately to complete their registration and gain access to Nigeria’s premier law reporting platform before all 25,000 slots are filled.

by Legalnaija | Feb 9, 2026 | Blawg

Introduction

Creativity is no longer a side conversation in Nigeria; it is a major economic driver. From music and film to digital content, fashion, and visual arts, creative works now sit at the intersection of culture, commerce, and investment. As the sector grows, so does the need for legal structures that protect creators, reassure investors, and regulate exploitation. Nigeria, like many jurisdictions, has enacted laws to govern the creative and entertainment space, with the intention of protecting creators, consumers, investors, and other stakeholders alike.

Beyond statutes, contracts remain the primary vehicle through which parties structure their relationships. Nigerian courts have consistently affirmed that parties are bound by the terms of their agreements, provided such terms are not inconsistent with the law. Where rights are breached—whether contractual or statutory—the law provides remedies. In theory, therefore, the framework for protecting creators is robust. In practice, however, the problem is rarely the absence of law or contracts; it is enforcement. Piracy persists, contractual breaches are commonplace, and litigation is often slow, expensive, and commercially draining. These realities weaken creators’ confidence and, more importantly, discourage structured investment into the creative economy.

Contracts: Where Enforcement Begins—and Often Fails

In an era where creative output is increasingly commercialised, it is surprising that many creators still enter work arrangements without clear, professionally drafted agreements. A well-drafted contract clarifies ownership, revenue sharing, royalties, duration, and exit rights, and significantly reduces enforcement disputes. Conversely, vague or informal arrangements leave parties relying on implied terms and goodwill, both of which offer limited protection when disputes arise.

A recurring issue in creative contracting is the failure to clearly define ownership and royalty structures. This omission often leads to disputes over intellectual property, revenue entitlement, and control of works long after the relationship has ended. Equally problematic are so-called “backdoor agreements” and one-sided standard form contracts imposed by dominant industry players. These agreements may technically be valid but are structured to shift risk almost entirely onto creators, leaving them with limited bargaining power and little room to enforce their rights.

Even where contracts are properly drafted, enforcement remains a challenge. Delays in litigation, cost of legal representation, evidentiary burdens, and power imbalances between parties often mean that creators abandon valid claims. In effect, contractual rights exist on paper but are commercially difficult to vindicate.

Compliance: The Silent Weak Link

Nigeria has several regulatory and administrative bodies tasked with protecting and regulating creative works. These include the Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC), the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC), and approved collecting management organisations. These institutions are designed to support enforcement through registration, licensing, monitoring, and rights administration.[3]

However, compliance remains weak on both sides. Many creators are unaware of registration requirements, collective management structures, or reporting mechanisms that could strengthen their enforcement position.[4] On the institutional side, enforcement agencies are often under-resourced and insufficiently accountable, resulting in inconsistent monitoring and limited deterrence against infringement.[5] Creativity may be artistic in nature, but it is also a commercial asset. Without a stronger compliance culture, neither creators nor investors can fully benefit from the value chain.

www.legalnaija.com/store

Why Court-Based Enforcement Is Often Unrealistic

Litigation has traditionally been the default mechanism for enforcing rights, but it is ill-suited to the realities of the creative industry. Despite reforms such as small claims procedures and specialised court divisions, court processes remain slow and adversarial.[9] Creative disputes often require urgent intervention—particularly in cases involving royalties, ongoing exploitation, or reputational harm. Prolonged litigation can outlive the commercial value of the work in dispute.

Additionally, public court proceedings may expose sensitive commercial information and damage business relationships. For creators whose careers depend on collaboration, reputation, and public perception, a legal victory may still result in long-term commercial loss.[10]

The Case for ADR in Creative Disputes

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) offers a more practical and commercially sensitive approach to enforcing creators’ rights. Mediation and arbitration allow parties to resolve disputes confidentially, efficiently, and with greater control over outcomes. In a relationship-driven industry, ADR preserves professional relationships while still providing enforceable outcomes.

ADR is particularly suited to creative disputes because of its flexibility. Parties can appoint neutrals with industry expertise, agree on timelines, and craft remedies that go beyond monetary compensation. Rather than a compromise, ADR represents a strategic enforcement tool that aligns legal protection with commercial realities.

Structuring Creative Deals with ADR in Mind

Effective enforcement begins at the contracting stage. Creative agreements should incorporate clear dispute resolution clauses that prioritise negotiation and mediation before escalation to arbitration or litigation. ADR mechanisms should also be considered during contract performance and not only after disputes arise. By embedding ADR into the lifecycle of creative transactions, parties create a predictable and investor-friendly framework for resolving conflict.

Recommendations

Strengthening enforcement in the creative sector requires a shift in mindset rather than wholesale legal reform. Creators must take contracting seriously and engage legal advice early, particularly on ownership, royalties, and dispute resolution. Regulatory agencies should adopt more transparent, technology-driven monitoring systems and actively promote ADR as a first-line enforcement mechanism. Investors and platforms, on their part, should prioritise fair contracting and compliance as part of risk management. Ultimately, a culture that treats creativity as both art and business will better protect rights, attract investment, and sustain growth.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s creative industry stands at a critical point. The laws exist, contracts are commonplace, and talent is abundant. What remains is the ability to enforce rights in a manner that is timely, commercial, and sustainable. By strengthening contracts, improving compliance, and embracing ADR, creators can move from paper rights to practical protection, and the industry can evolve into a truly investible ecosystem.

References

- Copyright Act, 2022 (Nigeria). Provides statutory protection for literary, musical, artistic, audiovisual works, sound recordings and broadcasts, including civil and criminal remedies for infringement.

- G. Rivers State v. A.G. Akwa Ibom State (2011) 8 NWLR (Pt.1248) 31. Authority on the sanctity of contracts and the binding nature of agreements freely entered into by parties.

- Best (Nig.) Ltd v. Blackwood Hodge (Nig.) Ltd (2011) 5 NWLR (Pt.1239) 95.

Reaffirms the principle that courts will not rewrite contracts for parties.

- B.N. Ltd v. Ozigi (1994) 3 NWLR (Pt.333) 385. On freedom of contract and the enforceability of contractual obligations.

- Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC) – Establishment and enforcement powers under the Copyright Act, 2022.

- National Film and Video Censors Board Act, Cap N40, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004. Regulates film and video content distribution in Nigeria.

- Nigerian Broadcasting Commission Act, Cap N11, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004.

Governs broadcasting standards, licensing, and content regulation.

- Arbitration and Mediation Act, 2023 (Nigeria). Provides the modern legal framework for arbitration and mediation in Nigeria and supports the enforceability of ADR outcomes.

- Small Claims Court Laws and Practice Directions (Lagos State and other jurisdictions).

Introduced to reduce cost and delay in litigation, though with limited applicability to complex creative disputes.

- UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration (as adopted in Nigeria).

Influences arbitration practice and enforcement standards applicable to commercial and creative disputes.

Martha Osarugue Obakpolor is a results-driven legal practitioner and the Principal Partner of McCharis Legal Consult. She has built a reputation for providing strategic legal solutions in corporate and commercial transactions, compliance, ADR, and advisory services. With experience advising businesses, investors, and creatives, Martha is recognized for her ability to simplify complex legal issues, manage risk, and protect client interests while supporting sustainable growth.

by Legalnaija | Feb 2, 2026 | Blawg

Introduction

Artists, songwriters, producers and other stakeholders in the music and entertainment industries must comprehend the nuances of master and publishing rights. Each of these two separate but related rights governs distinct elements of a musical composition each with its own sources of income and legal ramifications.

Understanding Master and Publishing Rights

In the context of sound recordings master rights refer to the ownership of a master recording. These are frequently owned by the organization that provides funding for the recording, which could be the artist if it was self-funded or a record label. How the recording is used, distributed and reproduced in the media is up to the owner of the masters rights. Synchronization licensing or sync licenses for the use of recordings in movies or advertisements for instance is covered by master rights.

Important Legal Aspects of Masters Rights.

Under copyright legislation master rights serve as the cornerstone for the protection, commercialization and distribution of sound recordings. These rights comprise the established legal precedents pertaining to ownership duration licensing terms and the laws regulating their application and implementation.

- Ownership of Master Rights

- i) Artist Ownership

Frequently, independent musicians keep their master rights which allows them to control how the recording is used and receive full payment.

Control over Creativity and Finances.

Independent artists don’t require any permission from third party organizations to license their recordings for use on streaming services and sync partnerships along with other uses. By maintaining the master rights, they are better able to control the terms of use pricing and distribution methods for their songs.

The Difficulties Faced By Independent Artists:

While the master rights ownership is admittedly a more freeing and artistically inclined experience, it also means that the artist will have to be ready to cover the bills that come with production, marketing and distribution. Independent artists just starting out will most likely not have access to the resources and finances readily available in record labels, possibly restricting their capacity to succeed financially and gain market share.

- ii) Label Ownership

Artists often enter into contracts with record labels that include the acquisition of master rights. Some labels consider this to be an important part of the negotiation process and will not take no for an answer. The labels contribute to the cost of professional production marketing initiatives, distribution networks and recording sessions while the artists transfer ownership of their master recordings to the label either permanently or temporarily in return.

Revenue Sharing:

Artists are usually paid royalties on the earnings earned from the master recordings. Although the percentage varies depending on the contract many artists get between 10 and 20 percent of net profits. Labels maintain control of the majority stake which they defend as payment for their investment. Certain contracts contain clauses that let artists reclaim their master rights after a predetermined period of time or after fulfilling specific requirements.

- Duration of Master Rights.

The term of protection for master rights differs by the local jurisdiction, although it is usually for several decades.

International Standards (the Berne Convention):

The Berne Convention, which unifies copyright regulations among participant countries, establishes a 50-year period of protection for sound recordings starting from the date of publication. This time frame is extended by many nations such as the European Union to 70 years following the release of the recording or the death of the inventor.

Copyright laws in the United States:

For 85 years following publication or 120 years following invention whichever comes first, sound recordings made in the United States after February 15, 1972 are protected. Depending on state legislation and federal changes older recordings may be subject to different standards.

Understanding Publishing Rights

Conversely, the underlying composition—the melody arrangement and lyrics—is covered by publishing rights. Typically publishers and songwriters own these rights. They have authority over the works’ public performances, distribution and reproduction. Publishing rights are involved when a composition is licensed for covers or movie adaptations.

- Split ownership of publishing rights.

A music publisher and the songwriter or songwriters often share publishing rights which leads to a division of duties and royalties.

Songwriters’ Ownership:

Due to their role in the creation of the composition (melody and lyrics), songwriters are still entitled to publishing rights. This share could be anywhere between fifty percent and the majority of the rights depending on the terms of the contract. Ownership is divided equally among many songwriters who work together and this needs to be recorded in a split sheet to prevent disputes.

Earnings:

Songwriters are compensated with royalties for their synchronization, performance and mechanical rights. The role of the publisher may also give them administrative control over the licensing of their compositions.

Music Publishers’ Role in Ownership

Publishers manage the market, promotion and profit from the composition in return for a share of the rights. Among their duties are licensing the composition, obtaining synchronization and cover opportunities and collecting royalties.

Standard splits:

Songwriters and publishers typically share publication rights 50/50 but this is not always the case. Self-publishing independent songwriters keep all rights but they are also in charge of all marketing and administrative duties. In foreign markets the composer may be represented by sub-publishers who will keep a share of the publisher’s profits while permitting local licensing and royalties to be collected.

Examples of Legal Cases.

There have been notable court cases pertaining to publishing rights most of which have involved ownership transfers, license conditions and royalties.

Music Mills Inc. v. Snyder in 1985.

The Supreme Court considered a publisher’s right to retain a share of earnings from derivative works produced after the songwriter terminated the initial transfer of rights. The idea that the original creator maintains complete ownership of any rights that are terminated was upheld by the Court’s ruling in favor of the songwriter.

Williams v. Gaye (2018): A Case of Blurred Lines.

A lawsuit was filed against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for allegedly violating Marvin Gaye’s song Gotta Give It Up. The court found that there had been a violation of Gayes publishing rights and granted significant damages.

Conclusion

Intellectual property in the music industry is complicated as demonstrated by the relationship between master and publication rights. Participants need to be well-informed about these rights and their legal basis in order to optimize profits and reduce disputes. In order to guarantee fair and sustained business growth as the digital music economy develops these challenges must be addressed by robust legal frameworks and open processes.

Eniola Sultan Olatunji is a final-year law student of the University of Ibadan, and an aspiring corporate lawyer with a focus on Entertainment, Data Privacy, and Commercial Law. A talented writer, Eniola looks forward to working with top companies in the nearest future.

Sources

- Bolero Music: “Master vs Publishing Rights in Music IP” https://www.boleromusic.com/blog/master-vs-publishing-rights-music-ip

- Releese Help Center: “What is the difference between master rights and publishing rights? https://support.releese.io/hc/en-us/articles/23100485505947-What-is-the-difference-between-master-rights-and-publishing-rights

- Icon Collective: “How Music Royalties Work in the Music Industry” https://www.iconcollective.edu/how-music-royalties-work

- Case law: Mills Music, Inc. v. Snyder (1985), Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records Inc. (1991) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Upright_Music,_Ltd._v._Warner_Bros._Records_Inc

- U.S. Copyright Office – Circular 56A: Copyright in Sound Recordings https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ56a.pdf

by Legalnaija | Jan 30, 2026 | Blawg

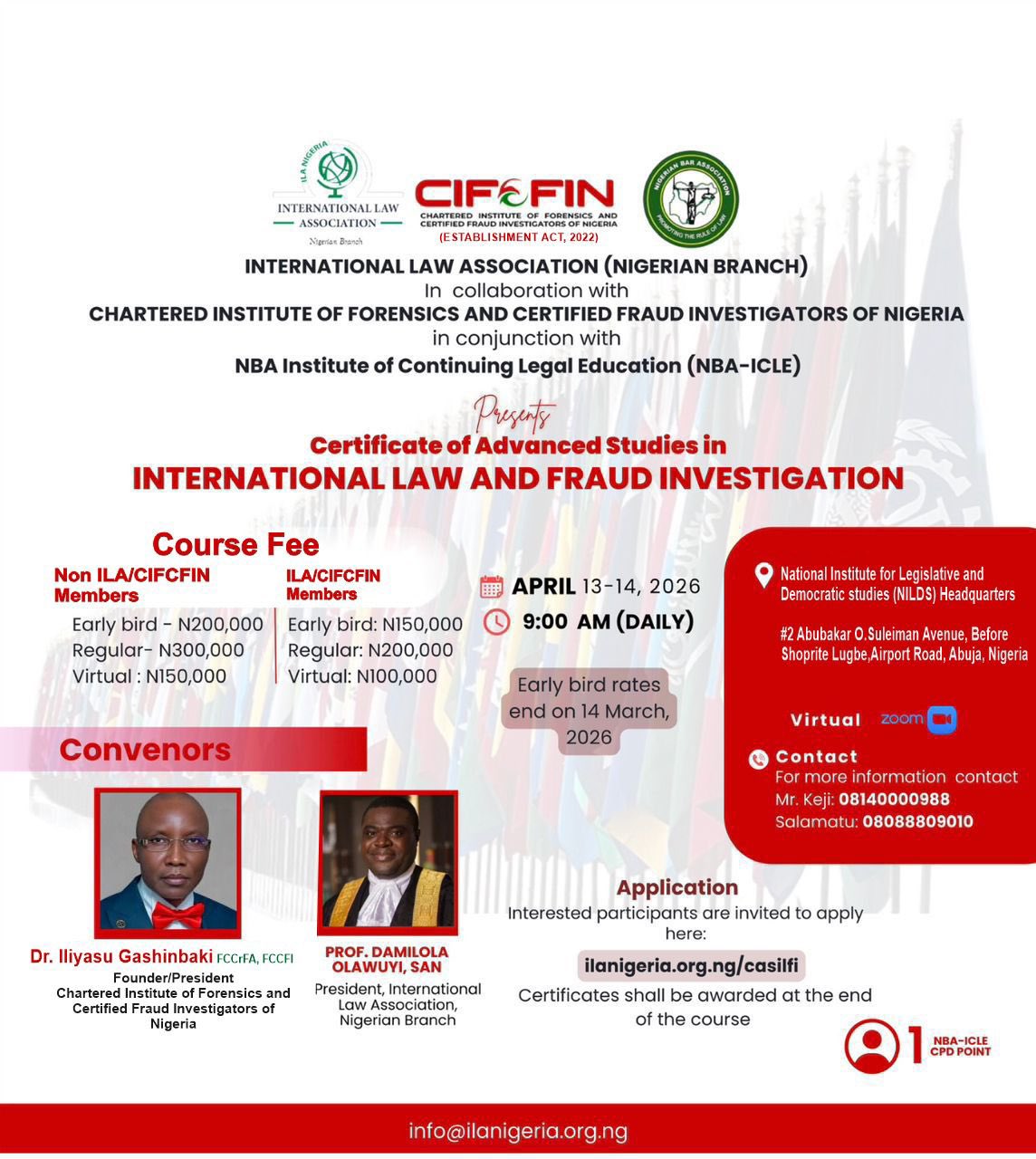

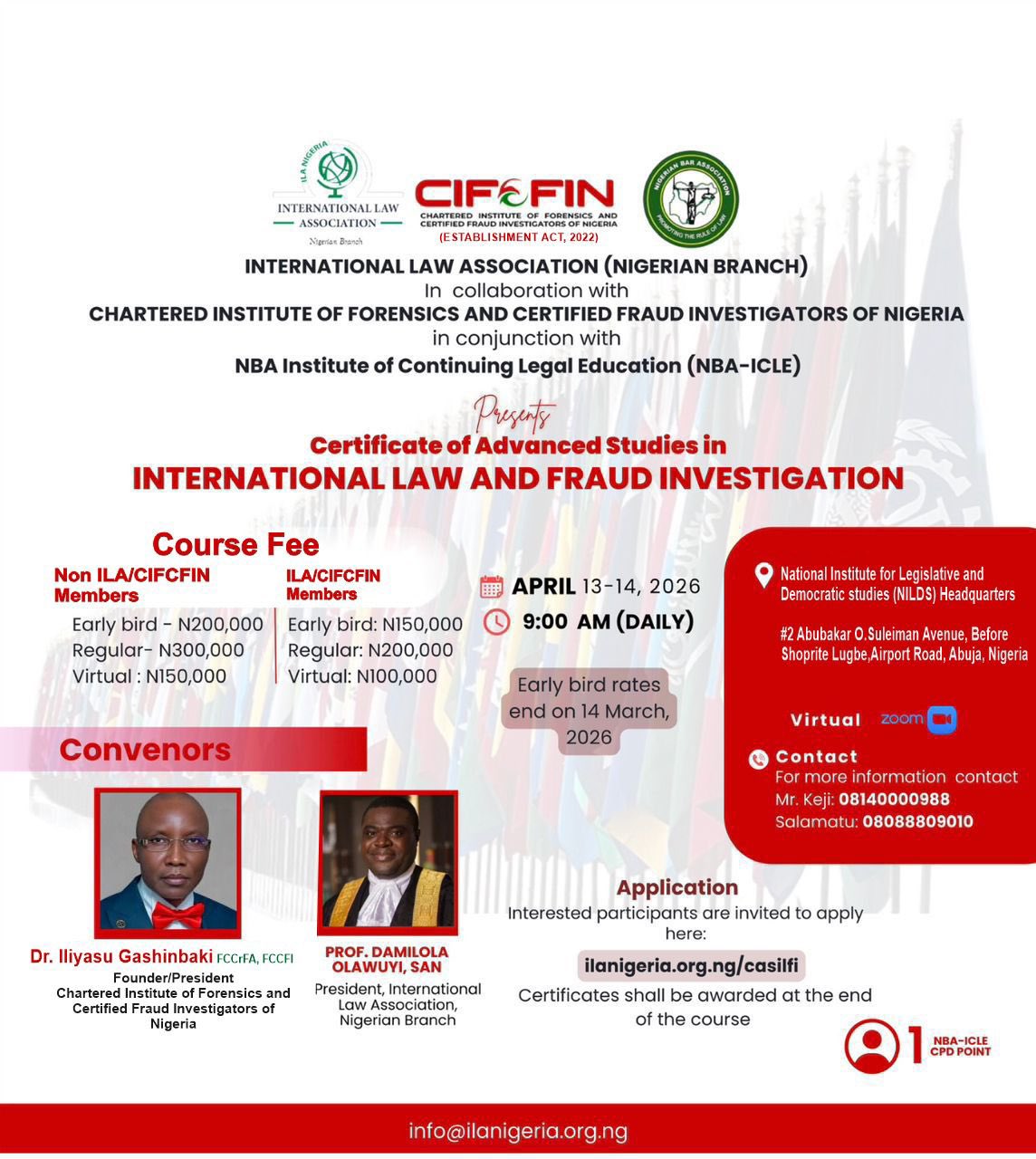

ILA Nigeria Announces three Innovative Advanced Certificate Courses in International Law for 2026

To advance the study, clarification and development of international law, the International Law Association (Nigeria Branch) is proud to announce its training schedule for 2026 with three innovative Certificate of Advanced Studies in International Law courses.

CERTIFICATE OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW/AFCFTA LAW AND POLICY

Date: April 13-16, 2026

Time: 9:00 am Daily.

Venue: National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies (NILDS)

Piwayi District,Off Umaru Musa Yar’adua Express Way, Airport Road Abuja.

Kindly register via this link: ilanigeria.org.ng/casilaft

This advanced certificate course is organized by the National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies (NILDS) and the International Law Association (ILA), in collaboration with the Nigerian Bar Association Institute for Continuing Legal Education (NBA-ICLE). NILDS is the apex capacity building and research agency for Nigeria’s National Assembly, established by the NILS Act of 2011 (amended in 2017 to cover democratic studies).

Given the importance of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) to state parties like Nigeria, through its strategic aims to create a single, unified market access across the continent, boost intra-African trade, promote economic diversification and industrialization, attract foreign direct investment, protect creativity and innovation, and reduce poverty, it is essential for all key stakeholders to understand how to maximize the full value of AfCFTA for national development.

The course will focus on the core sources and principles of international trade law, the practical challenges that limit their effective design and implementation especially in the context of AfCFTA; as well as innovative approaches and skillsets required to negotiate win-win international trade instruments in an increasingly globalized world. The course will also address hot topics and trends that are particularly important for Nigeria, including treaty implementation, trade remedies and dispute settlement.

The course is composed of intensive in-class sessions and free participation for registered course participants at the ILA Nigeria International Law Conference on illicit financial flows.

2. CERTIFICATE OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN INTERNATIONAL LAW AND FRAUD INVESTIGATION

Date: April 13-14, 2026

Time: 9:00am Daily

Venue: : National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies (NILDS)

Piwayi District,Off Umaru Musa Yar’adua Express Way, Airport Road Abuja.

Kindly register via this link: ilanigeria.org.ng/casilfi

This advanced certificate course is organized by the Chartered Institute of Forensics and Certified Fraud Investigators of Nigeria (CIFCFIN) and the International Law Association (ILA), in collaboration with the Nigerian Bar Association Institute for Continuing Legal Education (NBA-ICLE). CIFCFIN was established in 2022, as Nigerian’s apex institution dedicated to regulating and promoting forensic and fraud investigation practice in Nigeria. Chartered by the CIFCIN Establishment Act, 2022, CIFCFIN aims to provide a formidable platform for training, supervision and regulation of the professional practice of forensics and fraud investigation in all ramifications.

Given the importance of international law to national development, it is essential for key stakeholders in government, private practice, academia, and students to understand key multilateral agreements that, through their effective implementation, can accelerate fraud detection and corruption prevention, especially in critical economic sectors such as mining, oil and gas, banking, finance and alternative dispute resolution amongst others.

This advanced certificate course will focus on the core sources and principles of international law relating to fraud detection, the practical challenges that limit their effective design and implementation especially in the context of fraud investigation and prevention; as well as innovative approaches and skillsets required to negotiate win-win international instruments in an increasingly globalized world. The course will also address hot topics and trends that are particularly important for Nigeria, including anti-money laundering, proceeds of crime management, illicit financial flows and inter-agency synergy.

The course is composed of intensive in-class sessions and free participation for registered course participants at the ILA Nigeria International Law Conference on illicit financial flows.

CERTIFICATE OF ADVANCED STUDIES IN INTERNATIONAL LAW AND DIPLOMACY (WITH FOCUS ON INTERNATIONAL FINANCE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT)

Date: July 20-24, 2026

Time: 9:00 am Daily.

Venue: Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies (NIALS)

Supreme Court of Nigeria Complex, Three Arms Zone, FCT, Abuja.

Kindly register via this link: ilanigeria.org.ng/casil

Now in its fourth edition, this advanced certificate course is organized by the Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies (NIALS) and the International Law Association (ILA), in collaboration with the Nigerian Bar Association Institute for Continuing Legal Education (NBA-ICLE). NIALS was established in March 1979, as Nigerian’s apex Institution for research and advanced studies in law. The Institute is also accredited to offer Mandatory Continuing Legal Education for Lawyers.

Given the importance of international law to national development, it is essential for key stakeholders in government, foreign missions, private practice, academia, and students to understand key multilateral agreements that, through their effective implementation, can accelerate sustainable development, specifically on issues related to foreign direct investments, regional economic integration, human rights, peace and security, climate change and environmental protection, Artificial Intelligence, management of new technologies, economic diplomacy, development financing, and alternative dispute resolution amongst others.

The 2026 edition will focus on diplomacy and development and is designed to provide an in-depth examination of the core sources and principles of international law, the practical challenges that limit their effective design and implementation especially in the context of developing economies; as well as innovative approaches and diplomatic skillsets required to negotiate win-win international instruments in an increasingly globalized world. The course will also address hot topics and trends that are particularly important for Nigeria, including transfer of technology, the role of public-private partnerships in key economic sectors, business and human rights, and corporate social responsibility.

Certificates

Participants shall receive a Certificate of completion, as well as 1 CPD point of the Nigerian Bar Association-ICLE, upon conclusion of any of the courses.

Should you have any questions concerning the course, please do not hesitate to contact Moronkeji Kolawole: 08140000988, info@ila-nigeria.org.ng

by Legalnaija | Jan 29, 2026 | Blawg

Is the Defection of 21 Members of the Kano State House of Assembly an Automatic Forfeiture of Their Seats in the Light of Section 109(1)(g) of the Constitution?’

Sequence to the rift between Abba Kabir Yusuf and his political godfather, Senator Rabi’u Musa Kwankwaso, Abba Kabir Yusuf (the Governor of Kano state) was widely reported to have resigned his membership from the New Nigeria People’s Party (NNPP), the platform that brought him to power. This move was tagged by many as political betrayal and consequently generated public uproar across Kano State and beyond.

However, the uproar assumed a more complex legal colouration when, on the 26th day of January 2026, SaharaReporters reported that twenty-one (21) members of the Kano State House of Assembly had openly declared their defection from the NNPP to the All Progressives Congress (APC). This report was not speculative; as it was supported by a 4 minutes 16 seconds video, circulated widely which can be accessed at the SaharaReporter’s twitter handle, in which the said members, speaking in Hausa language, unequivocally announced their defection at the floor of the House.

While defection by a Governor has settled constitutional implications (or lack thereof), the same cannot be casually said of members of a legislative house. Therefore, the development raises certain legal questions: What happens where members of a House of Assembly defect to a political party that did not sponsor their election?

Does such defection automatically result in loss of seat?

These are the questions this article seeks to address in a few paragraphs below:

Starting with: A Defection to a political party is a process whereby a politician abandons the political party that sponsored him to office and joins another political party not as a result of a division or merger of parties.

The Supreme Court authoritatively defined defection. In R.S.H.A. v. Govt., Rivers State (2025) 7 NWLR (Pt. 1990) 591, the Court held:

‘The word ‘defection’ is synonymous with abandonment, desertion, apostasy, renunciation and rejection. In Politics, defection occurs when a person or group changes their membership from one Political Party to another.’

(Pp. 680-681, paras. H-C)

Importantly, defection is not speculative nor cosmetic. It must be proven. The Supreme Court further evinced in the same case that:

‘Defection is an active term. It manifests itself. It cannot be left to conjecture… For a person or group of persons to be said to have defected, the Political party from which they defected must, at least, be aware of such defection, and the political party where they defected to must also have evidence of their new members.’

(Pp. 681-682, paras. E-D)

Therefore, waving flags on television or issuing public declarations without acknowledgment by the receiving party does not, in law, amount to defection properly so called.

Going further, the law is settled that a President, Vice-President, Governor or Deputy Governor may defect without any constitutional consequence to their tenure. Such defection does not and cannot lead to forfeiture of office. This position is not the core of this discourse and needs no further elaboration here, as such, I say no more on this. However, members of the National Assembly and State Houses of Assembly stand on a different constitutional footing, Sections 68(1)(g) and 109(1)(g) respectively. Section 109(1)(g) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended) provides:

‘A member of a House of Assembly shall vacate his seat in the House if…

being a person whose election to the House was sponsored by a political party, he becomes a member of another political party before the expiration of the period for which that House was elected.’

Sections 68(1)(g) of the Constitution provides the same for defected members of the National Assembly, as such, no harm will be done if it’s not reproduced hereunder.

Per Mohammed, CJN held in Abegunde v. O.S.H.A. (2015) 8 NWLR (Pt. 1461) 314 that:

‘The provisions of section 68(1)(g) [In the instance case section 109(1)(g)] of the Constitution are very clear that the appellant… shall vacate his seat… when being a person whose election… was sponsored by a political party, he becomes a member of another political party before the expiration of the period for which that House was elected.’

The question now is: is the Loss of Seat Automatic? This is where public sentiment often parts ways with constitutional reality.

Although Section 109(1)(g) prescribes forfeiture of seat, it is not self-executing.

The Supreme Court settled this beyond controversy in R.S.H.A. v. Govt., Rivers State (Supra) where NWOSU-IHEME, JSC held:

‘The only competent authority to declare the seat of a member vacant for defection is the legislature to which he or she belongs…SECTION 109(1)(G) OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION IS NOT SELF-EXECUTING. THE ALLEGATION OF DEFECTION MUST BE PRESENTED BEFORE THE HOUSE IN SESSION. IF THE HOUSE IS SATISFIED THAT A MEMBER HAS DEFECTED, IT DECLARES HIS OR HER SEAT VACANT.’(Pp. 682-683, paras. H-E)[Capitalizations mine, for emphasis]

Put differently, defection does not operate automatically to vacate a seat. There must first be a legislative proceeding by the House such a member belong, and it’s the House that will declare the office vacant.

The Kano State House of Assembly has 24 members. Before this development, 3 members were already APC members, while the remaining 21 were elected on the NNPP platform, from which the Speaker and Deputy Speaker emerged.

With the defection of the 21 members, the practical question arises:

Does Kano State now have only three ‘competent’ lawmakers? The answer is a resounding NO. Because first, the allegation of defection must be tabled before the House. Second, it is only the House, sitting in plenary, that can determine whether defection has occurred and declare seats vacant. However, in this instance, the Speaker and Deputy Speaker are themselves part of the alleged defectors. The remaining three members are neither Speaker nor Deputy Speaker and Section 95(2) of the Constitution provides that where the offices of Speaker and Deputy Speaker are vacant or absent, members shall elect one among themselves to preside. The practical difficulty here is obvious:

Who elects whom among three members for the purpose of questioning the defection of twenty-one others?

This makes the situation legally and practically impossible.

One may, however, say that: can’t the Court intervene instead?The answer is equally settled, as the Supreme Court has consistently held that membership of a political party is an internal affair. In R.S.H.A. v. Govt., Rivers State (Supra), the Court reaffirmed:

‘Membership of a political party is a matter that is strictly within the domestic affairs of the political party and the courts have no jurisdiction to determine who the members of a political party are.’

Therefore, neither the Governor, nor any public office holder whatsoever, nor members of the public can validly approach the court to challenge the alleged defection where the House itself has not deliberated on it. After all, in the instant case, it is almost the entire membership of the House that is affected, thereby making deliberation practically impossible, as there are no members remaining to table the alleged defection, nor are there members to receive and deliberate upon it.

In conclusion, from the foregoing authorities and constitutional provisions, one conclusion stands firm: Defection by members of a House of Assembly does not automatically result in loss of seat.

There must be a legislative proceeding, duly conducted by the House, culminating in a declaration of vacancy. In the absence of such proceedings and given the peculiar paralysis within the Kano State House of Assembly, the twenty-one members remain, in the eyes of the law, valid members of the Kano State House of Assembly.Until the House speaks, the Constitution remains unoffended. And on this: I say no more, hoping I have passed the massage.

__________________________________________

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

isahbalagarba05@gmail.com or on 08100129131

by Legalnaija | Jan 21, 2026 | Blawg

Lagos, Nigeria – The Nigerian legal community has been thrown into mourning following the reported killing of Mr. Peter Ihiemekpen, Esq., a member of the Nigerian Bar. The incident, alleged to involve a police officer, has sparked outrage and renewed calls for accountability within law enforcement.

In a press statement, Lateef Omoyemi Akangbe, SAN, former Chairman of the NBA Lagos Branch, described the killing as “a painful and disturbing incident” that should concern not only the legal profession but all citizens who value human life and the rule of law.

“When a life is taken in circumstances alleged to involve a police officer, the issue goes beyond personal tragedy. It becomes a public matter that tests our commitment to accountability and justice,” Akangbe said.

He emphasized that while reports indicate the officer involved is in custody, justice requires more than an arrest. “It requires a careful, transparent, and credible investigation that allows the truth to emerge and reassures the public that the process is not compromised,” he added.

Akangbe called for the immediate establishment of an independent panel of investigation to examine the incident fully and openly. He stressed that where wrongdoing is established, prosecution must follow in accordance with the law.

The Senior Advocate also highlighted the urgent need for meaningful police reforms, focusing on professionalism, restraint, and respect for human dignity. “A society that truly values life must show it through action. Justice for Mr. Peter Ihiemekpen is not only about addressing one tragic loss, but about affirming the kind of country we want to be,” he concluded.

The Nigerian Bar Association is expected to issue further statements as investigations progress.

by Legalnaija | Jan 16, 2026 | Blawg

PREAMBLE

Imagine a construction project in Lagos, with five contractors, each from different jurisdictions. A dispute arises over delays and cost overruns. In one of the situations, the arbitration clause kicks in but halfway through the parties realize that they need some sort of interim judicial relief to freeze assets, and at the same time exploring mediation as a way to preserve commercial relationships. By the time the arbitral tribunal is prepared, the dispute has splintered into other court arbitration and mediation proceedings, each proceeding at its own speed, costing each millions[1]. The attempt to create order is yet another site of war.

This is where hybrid models of dispute resolution hold the most promise. Hybrids offer a flexible and less expensive means of coping with the increasing complexity of commercial transactions by incorporating the strengths of litigation, arbitration, mediation and expert determination. Yet, while these models are the future of dispute resolution, these models also raise thorny legal and procedural questions about enforceability, fairness and compatibility with existing legal frameworks.

This essay explores the potential and the pitfalls of hybridizations, particularly, whether hybridization is a viable prospect within Nigeria’s developing dispute resolution marketplace.

NATURE OF HYBRID MODELS IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION

Hybrid models are processes that blend two or more forms of dispute resolution within one process, either occurring sequentially or simultaneously, in order to improve efficiency, fairness and enforceability. They are born out of the understanding that litigation, arbitration or mediation alone cannot respond to the needs of every dispute.

Types of Hybrids

The hybrid ones have included the most recognized of these models:

- Med-Arb: where mediation is attempted first, and if mediation fail, the case proceeds to arbitration.

- Arb-Med-Arb: becoming popular in Singapore and Hong Kong, arbitration is initiated, mediation is attempted, and if mediation is unsuccessful, arbitration picks up where it left off.

- Lit-Arb: courts and arbitral tribunals working in tandem, usually for interim measures, but also for recognition of awards, and joinder of non-signatories.

- Multi-tier clauses: sometimes require negotiation → mediation → arbitration/litigation as a condition precedent to each step up the ladder.

Legal Recognition

Internationally, these models are backed up by instruments such as the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration[2], the New York Convention of 1958[3] and, more recently, the Singapore Convention on Mediation of 2019[4].

In Nigeria, the new Arbitration and Mediation Act 2023 (AMA) has made mediation and hybrid processes a central feature of the law, enabling for example, in Section 67, the enforceability of settlement agreements resulting from mediation[5]. The Act is consistent with international standards[6] and has provided Nigeria the opportunity to begin incorporating hybrid processes into its commercial dispute resolution culture[7].

Opportunities of Hybrid Models in Complex Commercial Cases

The hybrid form of dispute resolution has a number of distinctive strengths, especially in a time when a commercial dispute has moved from a single linear dispute to rather a multi-factored potential conflict involving cross-border trade, digital assets, and technical partnerships.

- Efficiency and Cost Effectiveness: One of the most lauded advantages of hybrid models like Med-Arb is the ability to blend the expediency of mediation with the finality of arbitration[8].

- Flexibility for Complex, Multi-Party Disputes: Hybrid processes are very well suited to technical disputes involving multiple stakeholders. These hybrids enable parties to work through temporary complicating technical details in a non-adversarial way before they must enter into adversarial decision-making[9].

- Preservation of commercial relationships: in Nigeria’s commercial ecosystem, networks and reputation are frequently more valuable than the contract itself, the hybrid process’s incorporation of mediation makes it possible for relationships to not be irreparably damaged[10].

- Enforceability in International Frameworks: Nigeria, having ratified the 1958 New York Convention, subject to enforcement as an arbitral award is that Nigeria acceded to it in 1970. In addition, as the Singapore Convention on Mediation, which Nigeria has signed but not yet ratified, is expected to enter into force soon, mediated settlements may increasingly gain international enforceability[11].

- Institutional Development and Nigeria’s Arbitration Hub Aspirations: Hybrid dispute clauses are increasingly being adopted in model rules by relevant institutions[12]. This makes Nigeria now positioned as the natural centre for the resolution of a Africa continent wide commercial disputes under AfCFTA giving local and foreign investors greater confidence with hybrid processes[13].

CHALLENGES OF HYBRID MODELS IN COMPLEX COMMERCIAL CASES

Although hybrid dispute resolution mechanisms can work enormously well, there are legal, cultural, and institutional barriers to hybrid dispute resolution in Nigeria and across Africa.

- Concerns About Neutrality: On a scale of neutrality and role conflicts such as Med-Arb, the same individual is often criticised for being both mediator and arbitrator[14].

- Absence of Clear Legislative Framework: AMA is silent on hybrid models, therefore, this legal uncertainty discourages parties from creating Med-Arb clauses in contracts with doubt about the legality and recognition provided by Nigerian courts[15].

- Judicial Attitudes and Enforcement Risks: In recent years, some courts have been interventionist with arbitration. Without judicial buy-in, hybrid settlements may have resistance in enforcement[16].

- Cultural Resistance and Awareness Gaps: Hybrid systems can be viewed as “experimental” or less legitimate. Lawyers often resist mediation stages, noting the impact they have upon professional fees. This cultural challenge remains the most daunting obstacle to hybrid adoption[17].

Judicial and Practical Considerations for Nigeria

There are some judicial and practical realities that must be grappled with, for hybrid systems to flourish as part of the Nigerian dispute resolution landscape. AMA has established the paradigm of ADR as modern, but it is mute on hybrids and thus leaves much room for judicial creativity and legislative tweaking.

- The Role of the Nigerian Judiciary

The courts remain the arbiters of enforceability. It follows that Nigerian judges must:

- Recognize Med-Arb/Arb-Med Clauses as Enforceable: In Mekwunye v. Imoukhuede, the Court reaffirmed the sanctity of arbitration agreements, but said nothing about hybrids[18]. A progressive attitude that extends this deference to Med-Arb clauses is crucial.

- Ensure Confidentiality Protections: Courts must develop jurisprudence to allay parties concerns that confidential mediation disclosures could taint arbitration. Comparative practice from the Hong Kong courts who require written waivers prior to a mediator being able to act as an arbitrator provides a workable Nigerian adaptation[19].

- The Legislature and Hybrid Gaps

AMA, though a positive development in this respect, does not codify these hybrid models. A future amendment could look to:

- Singapore’s Med-Arb framework that explicitly provides rules for the transition from mediation to arbitration[20].

- China’s CIETAC Arbitration Rules re-institutionalize Arb-Med-Arb as a dominant path, demonstrating the success of hybrids when they supported by legislation[21].

- Codification would provide certainty to parties and courts and would incentivize corporate actors to use these clauses in contracts.

Comparative Insights and Global Lessons

The various jurisdictions that have tried Med-Arb, Arb-Med and Arb-Med-Arb contain lessons that Nigeria can learn from in bolstering her commercial dispute resolution landscape.

- Singapore: Institutional Innovation

Singapore is at the forefront of hybrid processes internationally, primarily because of the Arb-Med-Arb Protocol (2014) it has established by collaboration between the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) and the Singapore International Mediation Centre (SIMC). Within this system:

- Arbitration is initiated, only to be diverted to mediation.

- If mediation succeeds, the settlement can be transformed into a consent award that is enforceable under the New York Convention (1958).

- In case the mediation does not succeed, arbitration will continue where it left[22].

- China: Cultural and Institutional Acceptance

In China Arb-Med is embedded in the rules of the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC). Arbitration cases regularly recommend mediation. If the mediation is successful, the result can be recorded as an arbitral award.

China’s success is underpinned by two factors:

- A cultural Confucian bias towards harmony and compromise[23].

- State support in the form of legal and institutional frameworks.

- Hong Kong: Judicial Caution

The courts in Hong Kong, in particular, have taken a more conservative approach when it comes to neutrality issues in Med-Arb. In Gao v. Keeneye, the court disallowed a Med-Arb settlement award because the mediator/arbitrator had obtained confidential information during the mediation process that interfered with his neutrality[24].

- European Union: Encouraging but Fragmented

ADR is also promoted at the EU level through the European Directive on Mediation (2008/52/EC), which encourages courts and other institutions to refer cases to mediation. But, the EU has not cemented hybrid models into the region, it is still left to the individual member states.

- United States: Pragmatism in Hybrids

Med-Arb in the United States is becoming more popular in labor disputes and complicated commercial disputes. Court supervised settlements, such as those in United States v. Miami exemplify this combination of mediation and enforceable adjudication[25].

Lessons for Nigeria

AMA provides a timely legal umbrella that can accommodate the embedding of hybrid models. But, global lessons need to be translated into practice within Nigeria:

As Singapore has done, Nigeria may consider incorporating Arb-Med-Arb into the various rules and regulations of its institutions, starting with the oil & gas, maritime, and fintech disputes where there is a strong need for cross-border enforceability.

Just as in the Arb-Med model[26], it is generally elders who fill the role of mediator and judge in Yoruba and Igbo conflict resolution.

The AMA can build on this by formally incorporating community mediation practices into institutional ADR and ensuring enforceability.

The Gao Haiyan case warns against impartiality risks where the mediator become arbitrator. The Nigerian government can prevent this by: Amending institutional rules to require written consent from parties before a mediator can act as an arbitrator in the same dispute.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NIGERIA

The potential for hybrid solutions to the resolution of commercial disputes lies in a joint undertaking by institutions.

- Judiciary

- Develop Precedent on Hybrids: Just as in United World Ltd v. MTS Ltd, courts have upheld the autonomy of the arbitral process, they should also explicitly grant the same recognition they give to consent awards achieved through arbitration to those achieved through mediation[27].

- Issue Practice Directions: Like the Federal High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, old practice directions could be introduced to aid in recognition and enforcement of hybrid outcomes.

- Training Judicial Officers

- Legislature

- Codify Arb-Med-Arb Procedures: Similar to Singapore, the National Assembly should pass additional regulations strictly addressing Arb-Med-Arb procedures to provide clarification about neutrality and enforceability.

- Sector-Specific Hybrid Rules: Laws regulating maritime (NIMASA Act), oil and gas (Petroleum Industry Act)[28], and fintech could expressly provide for hybrid dispute resolution for sectoral disputes.

- Budgetary Support

- Executive

- Policy Framework: The Federal Ministry of Justice can publish a National ADR Policy in which Arb-Med-Arb is made compulsory for federal contracts of a certain value.

- Capacity-Building

- Public-Private Partnerships: the executive can promote PPPs to fund ADR centres with hybrid panels in order to lessen the backlog resulting from government related disputes.

- Private Enterprises

- Insert Hybrid Clauses

- Support Institution Building

- Cost Saving Incentives

CONCLUSION

Commercial disputes are the lifeblood of economic life and the mode in which they are settled often determines economic life or death for businesses. Nigeria stands at a critical juncture, litigation has been too rigid, arbitration and mediation have offered alternatives but neither alone is sufficient for the complexity of the modern cross border commerce. The hybrid model, combining the certainty and finality of arbitration with the flexibility of mediation, provides a compromise which is consistent with international best practices and Nigeria’s own participatory and consensus-oriented culture.

If Nigeria dares to take action now, it will not only attract investor’s confidence but export dispute resolution expertise across Africa. In ten years, the Lagos Arb-Med-Arb Protocol could be as much a point of reference globally as the Singapore Convention is.

[1] Gary Born, International Commercial Arbitration (3rd edn, Kluwer 2021) 54

[2] UNCITRAL, Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration (2006, with amendments)

[3] New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (1958)

[4] United Nations, Singapore Convention on Mediation (2019)

[5] Arbitration and Mediation Act 2023 (Nigeria), s 67

[6] By ALF, “A Review of the Arbitration and Mediation Act 2023: Charting A New Course In Nigeria.– Alliance Law Firm” https://alliancelawfirm.ng/a-review-of-the-arbitration-and-mediation-act-2023-charting-a-new-course-in-nigeria/#:~:text=The%202023%20Act%2C%20according%20to,Nigerian%20alternative%20dispute%20resolution%20practice. accessed October 1, 2025

[7] “The Nigerian Arbitration and Mediation Act 2023: A Comparison with the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 2004 and Global Practices” (International Bar Association) https://www.ibanet.org/the-nigerian-arbitration-and-mediation-act-2023#:~:text=The%20enactment%20of%20the%20Arbitration,permitting%20third%2Dparty%20funding%20arrangements. accessed October 1, 2025

[8] Born, G., International Arbitration and Forum Selection Agreements (Kluwer Law 2021) 233

[9] Centre VM, “UNDERSTANDING HYBRID ADR ” (VIA Mediation Centre) https://viamediationcentre.org/readnews/ODM4/UNDERSTANDING-HYBRID-ADR accessed October 1, 2025

[10] OB Akinola: Mediation, Conciliation and the Construction Industry in Nigeria: Catalysts or Clogs? African Journal of Law, Ethics, & Education [AJLEE] Vol. 8, No. 3 (2025) https://ajleejournal.com [ISSN: 2756 -6870]

[11] United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation (Singapore Convention, 2019)

[12] such as the Lagos Court of Arbitration and the Nigerian Institute of Chartered Arbitrators

[13] Nigerian Institute of Chartered Arbitrators, Model Arbitration Rules 2023 (NICArb, Lagos)

[14] Stipanowich T, “‘Switching Hats’: Developing International Practice Guidance for Single-Neutral Med-Arb, ArbMed, and Arb-Med-Arb — International Mediation Institute” (International Mediation Institute, May 4, 2021) https://imimediation.org/2021/05/04/switching-hats-developing-international-practice-guidance-for-single-neutralmed-arb-arb-med-and-arb-medarb/#:~:text=Concerns%20Regarding%20Mixed%20Roles,to%20enforce%20a%20final%20award accessed October 1, 2025

[15] Arbitration and Mediation Act 2023 (Nigeria), esp. Parts I & III

[16] Mekwunye v. Imoukhuede (2019) 13 NWLR (Pt 1690) 439 (SC)

[17] Okorie C and Okorie K, “ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION IN NIGERIA: ISSUES AND CHALLENGES” (unknown, April 12, 2024) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379759340_ALTERNATIVE_DISPUTE_RESOLUTION_IN_NIGERIA_ISSUES_AND_CHALLENGES#:~:text=adjournments%2C%20and%20inadequate%20manpower%2C%20which,challenges%20associated%20with%20court%20litigations. accessed October 1, 2025

[18] Mekwunye v. Imoukhuede (2019) 13 NWLR (Pt 1690) 439 (SC)

[19] Gao Haiyan v. Keeneye Holdings (2011) HKCFI 2401 — Hong Kong Court of First Instance on Med-Arb neutrality

[20] Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) & Singapore International Mediation Centre (SIMC) Arb -MedArb Protocol 2014

[21] China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) Arbitration Rules (2015), Article 47

[22] SIAC & SIMC Arb-Med-Arb Protocol, 2014

[23] Ali, Shahla F., The Legal Framework for Med-Arb Developments in China: Recent Cases, Institutional Rules and Opportunities (October 18, 2016). Dispute Resolution International, DRI 119. PP. 119 -132, 2016 , Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3216252

[24] Gao Haiyan v. Keeneye Holdings (2011) HKCFI 2401

[25] United States v. City of Miami, 664 F.2d 435 (5th Cir. 1981)

[26] OGBOBE S S ‘The Roles Of Elders In Alternative Dispute Resolution: Nigeria In Context’ NOUN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PEACE STUDIES AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION [NIJPCR] VOL. 2, NO. 2, AUGUST, 2022

[27] Lagos Multi-Door Courthouse Annual Report 2021

[28] Petroleum Industry Act 2021

Ajiboye Nathaniel Adebayo is a 300 Level student of University of Ilorin. His email: ajiboyenathanieladebayo@gmail.com

by Legalnaija | Jan 16, 2026 | Blawg

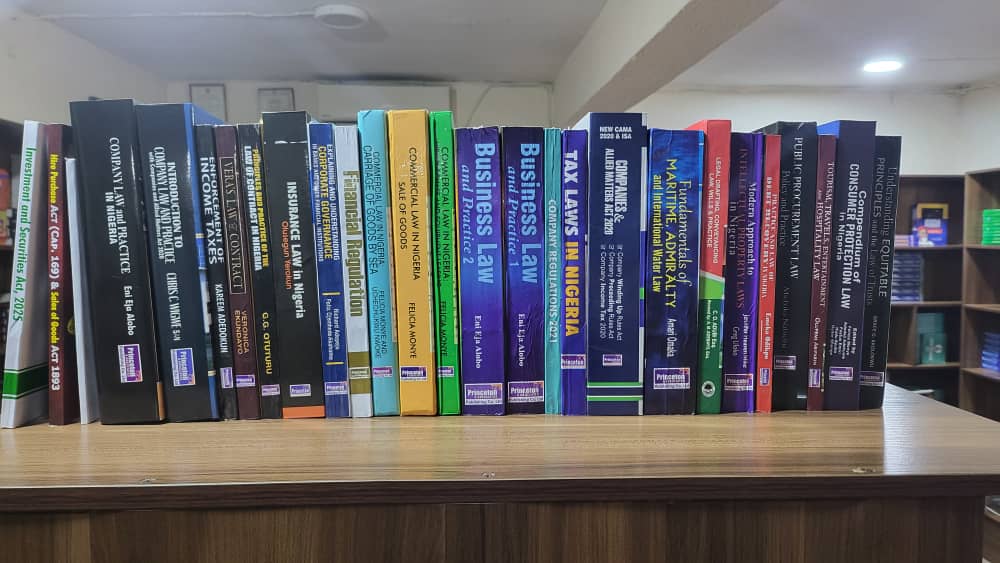

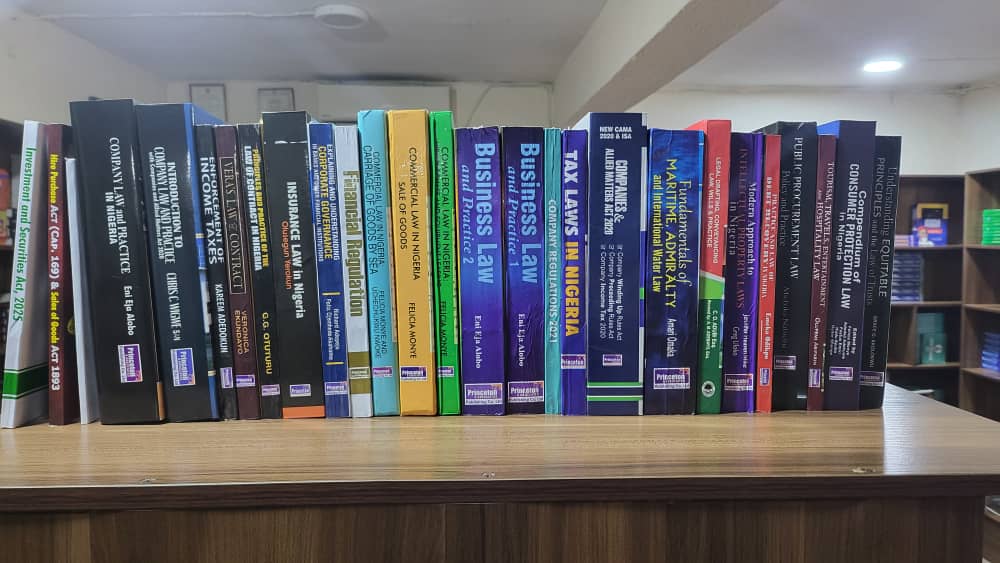

A well‑stocked law firm library is more than just a collection of books—it is the intellectual backbone of practice. Whether your firm specializes in Dispute Resolution or Commercial Law, the right resources can sharpen expertise, support client service, and keep practitioners ahead of evolving legal trends. At Legalnaija Bookstore, we believe every firm should curate its shelves with texts that reflect its practice focus.

For Dispute Resolution Experts

Dispute resolution requires mastery of negotiation, arbitration, and litigation strategies. Practitioners benefit from books that combine practical guidance with theoretical depth. In this book bundle for Dispute Resolution and Litigation experts, we have over 27 books, essential titles include;

- Casebook on Criminal Law by A.M. Adewale

- Evidence Act 2011

- High Court Civil Procedure Rules

- Principles of Criminal Law

- Principles of Evidence by T. Akinola Aguda

- Criminal Law Annotated with Cases

- Introduction to Criminal Law by Chris Ugwueze

- Principles Governing Bail in Nigeria

- Human Rights and Enforcement of Criminal Law

- The Process and Practice of Dispute Resolution and Arbitration in Nigeria

- Alternative Dispute Resolution and Arbitration in Nigeria

- Legal Research and Writing in Nigeria

- Basic Concepts in Legal Research Methodology

- Casebook on Criminal Law

- Nigerian Criminal Law in Perspective –

- Practical Approach to Civil and Criminal Litigation in Nigeria

- Evidence Law Clinic

- Criminal Evidence in Nigeria

- How to Recover Properties of Dead Relations

- Introduction to Evidence Law in Nigeria

- Personal Injury Law

- Modern Customary Court in Nigeria

- Modern Law of Evidence and Appellate Practice in Nigeria

- Essays on Criminal Justice

- Criminal Investigation and Prosecution Proceedings

- Landlord and Tenants under Nigerian Laws

- Arbitration Law: Practice & Procedure

These resources equip dispute resolution lawyers with the tools to manage conflicts efficiently, whether in courtrooms or at the negotiation table. You can order this bundle of books here.

For Commercial Law Experts

Commercial law practitioners navigate contracts, corporate governance, and regulatory compliance. Their libraries should emphasize texts that provide clarity on transactional practice and business law. In this bundle for commercial law experts, the list of books includes;

- Commercial Law in Nigeria – Carriage of goods by sea

- Financial Regulation Act

- Explaining and Understanding Corporate Governance in Banks and other Financial Institutions

- Insurance Law in Nigeria

- Principles and Practice of the Law of Contract in Nigeria

- Vera’s Law of Contract

- Enforcement of Income Taxes

- Introduction to Company Laws and practice in Nigeria

- Company Law and practice in Nigeria

- Data protection Act

- Hire Purchase Act

- Investment & Securities Act

- Commercial Law in Nigeria: Sale of Goods

- Commercial Law in Nigeria: Hire Purchase and Equipment Leasing

- Business Law 1

- Business Law 2

- Company Regulations 2021

- Tax Laws in Nigeria

- Companies and Allied Matters Act

- Fundamentals of Maritime, Admiralty and International Water Law.

- Legal drafting, conveyancing law, Wills and practice

- Modern Approaches to Intellectual Property Law in Nigeria

- Practice and Recovery in Nigerian Law

- Public Procurement Law

- Tourism, Travels, Entertainment and Hospitality Law.

- Compendium Of Consumer Protection in Nigeria

These books help commercial law experts provide sound advice to businesses, investors, and corporate clients. You can also order this set of books here.

Why Your Library Matters

A law firm’s library is not just about prestige—it is about preparedness. Dispute resolution experts rely on authoritative texts to argue persuasively and settle disputes effectively. Commercial law experts depend on them to structure transactions and safeguard clients’ interests. By curating your library through Legalnaija Bookstore, you ensure access to resources that match your practice focus and elevate your firm’s intellectual capital.

Plus we deliver nationwide. For more information and enquiries, please call or text Legalnaija on 09029755663 or send an email to hello@legalnaija.com , you can also visit our bookstore on www.legalnaija.com/store

by Legalnaija | Jan 4, 2026 | Uncategorized

They do say the law is an ass, but should it be so?

Can a trial court judge rewrite the law on rape sentence?

This girl’s name was Iruoghene Ogodo, an 11-year-old, and the Appellant was Mr. Afor Lucky, on 7th April 2012 he sent her to buy ‘pure water’ (sachet water) for him, thereafter he lured her into his room and forcibly had sex with her. An innocent child; bleeding from a torn hymen and injured vaginal wall, as confirmed by PW3 (the chief medical officer). a girl at that age can’t, in our criminal corpus juris, give consent, as ordained in section 30 of the Criminal Code and a similar provision in section 39 of the Penal Code.

Mr Lucky was charged and arraigned at the Delta State High Court on one count charge of rape under section 358 of the criminal code Law of Delta state, 2006. He didn’t deem it appropriate to plead guilty in order to expedite the proceeding, perhaps he felt he could get away with it. So he pleaded not guilty of course, like almost every defendant, and even raised alibi (claiming he wasn’t even there on 7th April 2012). Prosecution called Four Witnesses proving forceful penetration; PW3 satured the Virginal wall injury, ruling out other causes like bicycle riding as sheepishly claimed by the defendant to be a cause among the causes of virginal injury, he counter called two witnesses to establish his innocence. At this point, some questions are certainly inevitable. Would a trial judge, faced with such barbaric evidence against an 11-year-old, impose 5 years imprisonment with hard labor OR N300,000 fine? A girl that in law cannot give consent?After plea of allocutus, can mitigation rewrite life imprisonment under section 358 to 5 years imprisonment?

This is what happened in the case of LUCKY V. STATE (2016) 13 NWLR (Pt. 1528) 128.

The Delta State High Court, found him guilty as charged. After the plea of allocutus seeking for mitigation of his sentence, he was consequently given a sham sentence of 5 years with hard labour or N300,000 fine instead of life imprisonment. And the question was: does the trial judge actually rewrite the law? Because section 358 of the Criminal Code Law of Delta State, 2006, under which he was charged, provides for life imprisonment. What was his plea of allocutus about to warrant such mitigation? And if they were so compelling, can it be just to the victim and even de jure for them to be considered in such a magnitude offense? After all, justice is a three-way traffic.

Surprisingly, Mr Lucky protested, he was unhappy with even that leniency, and appeal to court of Appeal on 17th November 2014, the appeal was dismissed. The learned wise men called it ridiculous, however, they said their hands were tied since state didn’t cross-appeal, as such can’t temper with the sentence. Supreme Court in 2016 also affirmed the conviction; lamented the ‘contumacious violation’ of law, but resisted tampering with the sentence since no appeal was made against it by the state. Justices like Ngwuta, Okoro, Galadima JCS called it mockery, attack on justice, yet law is an ass.

I have read the case before, when I wrote my article titled: ‘Is the plea of Allocutus a right or a privilege in Nigerian criminal proceedings?’ but not meticulously like this. Upon reading it again today, I am not in total agreement with the decisions of the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court that they can’t temper with the sentence in the absence of the appeal. Can they really not invoke powers under sections 16 & 22 Court of Appeal Act and Supreme Court Act respectively to correct the error? I read the case over and over, erudite justices in pain, quoting Nafiu Rabiu v. State, but where then did they get the restraint from?On rape punishment? Section 358 provides: ‘any person who commits the offence of rape is liable to IMPRISONMENT FOR LIFE.’ No discretion, no option of fine.The above provision is clear and unambiguous, life for rape. In this case, where then did the trial court get 5 years from? Of course, I am not unaware of the position that pursuant to section 311 of ACJA (2015) Judges are enjoined to consider mitigating factors while sentencing, but can the said power be exercised in the offense of this magnitude considering even the circumstances of this case? Or should we safely say courts upheld an ass?

In my humble view, both the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court could have invoked their general powers pursuant to sections 16 and 22 of the Court of Appeal Act and Supreme Court Act respectively to correct the error. The sections respectively give them jurisdiction of the court of first instance; that’s to act as if the case was initiated or prosecuted before them to correct or amend, inter alia, errors; specifically this case being errors of law, awherend any other order the lower court could have made. This enormous power was given judicial recognition and duly applied in the celebrated case of Inakoju v. Adeleke (2007) 4 NWLR (Pt. 1025) 427, per Niki Tobi, JSC( as he then was) who delivered the lead judgment,affirmed the act of the trial court in granting reliefs sought in the substantive matter even though those reliefs were not part of the grounds of appeal before the Court. The case reached the Court of Appeal by way of an interlocutory appeal, solely to determine whether the trial court had jurisdiction to entertain the matter. Upon resolving that issue in the affirmative, the Court of Appeal refused to remit the case back to the trial court and proceeded to determine the substantive suit, relying on section 16 of the Court of Appeal Act. This approach was endorsed by Niki Tobi, JSC, and the majority of the Justices of the Supreme Court, with the exception of Oguntade, JSC,(As he then was) who dissented.

For emphasis, section 16 of the Court of Appeal Act provides as follows:

‘The Court of Appeal may, from time to time, MAKE ANY ORDER NECESSARY FOR DETERMINING THE REAL QUESTION IN CONTROVERSY in the appeal, and may AMEND ANY DEFECT OR ERROR in the record of appeal, and may DIRECT the court below to inquire into and certify its findings on any question which the Court of Appeal thinks fit to determine before final judgment in the appeal and may MAKE AN INTERIM ORDER or grant any injunction which the court below is authorised to make or grant and may DIRECT ANY NECESSARY INQUIRIES or accounts to be made or taken and GENERALLY SHALL HAVE FULL JURISDICTION OVER THE WHOLE PROCEEDINGS AS IF THE PROCEEDINGS HAD BEEN INSTITUTED IN THE COURT OF APPEAL AS COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE and may RE-HEAR THE CASE in whole or in part or may REMIT it to the court below for the purpose of such re-hearing or may GIVE SUCH OTHER DIRECTIONS as to the manner in which the court below shall deal with the case in accordance with the powers of that court, or, in the case of an appeal from the court below in that court’s appellate jurisdiction, ORDER THE CASE TO BE RE-HEARD by a court of competent jurisdiction.’[Capitalizations mine,for emphasis]

Section 22 of the Supreme Court Act contains similar and equally expansive provisions, empowering the Supreme Court to exercise the jurisdiction of a court of first instance where justice so demands. So no harm will be done if I refuse to qoute it.

Hey, you, yes you!Hold back your dagger, I am merely saying this in the light of the wordings of the sections and the judicial pronouncement. I hope I am right. It wouldn’t be terrible even if I am wrong, but I believe the courts could have fallen back to the provisions to ensure the ungodly and ungrateful perpetrator of the heinous act faces the wrath of the law accordingly. And on that; I say no more.

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

isahbalagarba05@gmail.com or on 08100129131