by Legalnaija | Sep 2, 2021 | Uncategorized

BACKGROUND

By a circular dated February 5th 2021, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) directed all financial institutions to close bank accounts of persons or entities transacting in or operating cryptocurrency exchanges noting that facilitating payments for crypto currency exchange is prohibited in Nigeria. According to the CBN, the adoption of cryptocurrency in Nigeria will restrict the CBN’s ability to effectively perform its monetary policy and supervisory responsibilities. In addition, its use will largely undermine the CBN’s role in controlling money supply, posing risks such as loss of investments, money laundering, terrorism financing, illicit fund flows and criminal activities as cryptocurrencies are usually issued by unregulated and unlicensed entities.

Ironically, in what appears to be a policy turn around the CBN recently announced its plans to introduce a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) before the end of 2021. In making the announcement the CBN stated that the introduction of the digital currency will supplement cash, enhance the financial inclusion drive of the CBN, reduce the cost of cash management and enable innovations in Nigeria’s financial market.

A CBDC is a digital token or virtual form of a fiat currency of a particular country. It uses an electronic record or digital token to represent the virtual form of a fiat currency of a particular country (or region) A CBDC is centralized, it is issued and regulated by the competent monetary authority of the country.

The major conflict between central banks and cryptocurrency is the decentralized nature of cryptocurrency, so CBDCs offer governments an opportunity to take the benefits of the new financial technology without necessarily giving up their regulatory powers or control. An important similarity between the CDBC and cryptocurrency is that they both adopt blockchain technology, however the major difference lies in the CBDC being regulated by the government through the Central Bank.

BENEFITS OF CENTRAL BANK DIGITAL CURRENCY (CBDC)

- CBDCs have the potential to be more efficient than traditional fiat currency in terms of payment options since they are not limited by the pitfalls of the banking system

- CBDCs will reduce the cost of minting and storage of bank notes

- CBDCs’ banking operations will be available 24/7 and not subject to the limitation of banks’ opening and closing hours.

- CDBCs will make tax evasion and other fiscal crimes such as money laundering more difficult as users will need to undergo verification processes before they can use the CBDC

- CBDCs will aid the transition to a cashless economy.

Order via Legalnaija.com/shop

IMPLICATIONS OF THE INTRODUCTION OF CBDC

The adoption of CBDC will have significant implications for commercial and retail banks that are directly participating in monetary systems through accounts at Central Banks. In a wholesale CBDC model, the basis of existing currency transfer between the Central Bank and commercial banks with accounts in their system are transformed to use a distributed ledger. For banks with Central Bank accounts, this shift poses significant implications on how they engage and transact with the Central Bank.

Retail CBDC systems will have broader impacts on the economy as non-bank participants will have direct interactions with Central Banks. This is in contrast to wholesale systems where only licensed institutions interact with the Central Bank.

CBDCs can serve as an interest-bearing substitute to commercial bank deposits, with the introduction of this substitute commercial banks are likely to respond by changing the deposit rates they offer to savers and, because of the resulting impact on banks’ funding cost and the terms of the loans they offer to borrowers. [1]

As a new form of central bank money, CBDCs have the potential to affect central banks’ wider policy objectives, either by acting as a new monetary policy tool or through its effects on the portfolio choices of Individuals. Crucial to this is the flexibility provided by CBDC in responding to macroeconomic shock. [2]

HOW OTHER COUNTRIES ARE IMPLEMENTING CBDCs

CBDC systems vary significantly in their design and implementation based on the Central Bank and monetary policy of the currency system, but are largely aligned to either a wholesale or retail model.

Wholesale CBDCs are a digital evolution, enabled through distributed ledger technology of traditional reserves held at Central Banks by financial institutions. They are used only to transfer value between Central Banks and licensed participants with accounts at the Central Bank. Retail CBDCs bring the settlement and transparency advantages of distributed ledger technology to everyone. Individuals and businesses will be able to hold and interact with CBDCs independently of financial services institutions. [3]

Below are a list of the country’s leading in development of the CBDC

The most prominent CBDC project being implemented at this time is China’s digital renminbi or Digital Currency/Electronic Payments (DCEP) initiative, The use of the CBDC was on trial in Q4 of 2020 and reports show that China is working towards a phased release. China embarked on the project in 2014 and has positioned its development as a direct challenge to the global dominance of the U.S. dollar. While details of the project are still emerging, reports suggest that DCEP will use Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), and is intended to replace cash in circulation, and will be distributed through digital wallets.

As of 2020, The Central Bank of The Bahamas was preparing to launch the Sand Dollar, a digital version of its Bahamian dollar, which could potentially become the first active global CBDC . The Sand Dollar intends to make digital payment technologies more accessible to underserved communities. Users will be required to go through Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) compliance processes before transacting with the Sand Dollar.

The Marshall Islands plans to launch Marshallese Sovereign, a CBDC built on the Algorand blockchain whose purpose is to promote financial inclusion. Users will need to undergo verification processes before they can use the CBDC but the Marshallese government has emphasized that the CBDC will preserve users’ privacy.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has also explored releasing a CBDC, the digital euro, arguing that it could be a means to adapt to the continuing digitalization of the global economy. Likewise, the ECB has said that it may issue a CBDC if foreign CBDCs or “private digital payments” are widely adopted in Europe. It plans to consider whether it should initiate a CBDC project around mid-2021.

In addition to the aforementioned projects, South Korea, Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, and a few other countries are also considering launching CBDCs. While the U.S. does not yet have plans to launch a CBDC, the Federal Reserve has said that it is exploring how it could digitize the dollar in the future.

CONCLUSION

The proposed introduction of a CBDC in Nigeria is a welcome development, however the government should take into consideration the peculiar economic realities in Nigeria such as Inflation, engage in thorough research, engage and receive input from all relevant stakeholders and develop the CDBC in way that it is a better alternative to the fiat currency. It is also important to note that majority of the populace in Nigeria are not conversant with the use of technology. Therefore, in other to fully maximize the benefit of the CBDC there needs to be sensitization and education of the populace on how to use the CBDC and its benefits.

Some years ago, when ATMs were first introduced in Nigeria, it was met with great skepticism. However, save for the unbanked, nearly every Individual has an ATM card limiting cash handling. It is safe to presume that the introduction of a CBDC will have the same response and effect.

[1] https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/central-bank-digital-currency-a-literature-review-20201109.htm

[2] ibid

[3] https://advisory.kpmg.us/ Central Bank Digital Currency, The Rise of Digital Currency and the future of money December 2020

by Legalnaija | Sep 2, 2021 | Uncategorized

BACKGROUND

The jurisdiction of a court to entertain a matter is conferred on the court by the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended) or by the statute that created the court. Section 251(1)(g) of the Constitution confers on the Federal High Court the competence to entertain any admiralty matters in Nigeria to the exclusion of all other courts in the country. It is interesting to note that the scope of this admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court has become less clear following a number of recent court decisions. Prior to the promulgation of the 1999 Constitution, there existed a jurisdictional tussle on admiralty matters between the Federal High Court and the State High Courts. The Supreme Court resolved this jurisdictional wrangling in SAVANNAH BANK LIMITED V. PAN ATLANTIC SHIPPING & TRANSPORT AGENCIES[1]where the Court held that the Federal High Court and the State High Courts had concurrent jurisdiction over admiralty matters. The 1999 Constitution further settled the issue in section 251(1) which provides that the jurisdiction of the State High Courts is subject to the exclusive jurisdictional competence of the Federal High Court on specific subject matters listed in section 251, which includes “any admiralty jurisdiction.”

The application of the concept of simple contracts within the context of the subject matter jurisdiction of the Federal High Court has unsettled and rendered less defined the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court. The Supreme Court has endorsed the position that the Federal High Court does not possess jurisdiction in respect of simple contracts. Instead, it is the State High Courts that can exercise jurisdiction in respect of simple contractual claims.[2] This has created uncertainty regarding the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court as most admiralty matters are based on simple contracts.

The case under review examines the application of the concept of simple contracts by the Supreme Court in determining the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court. It also highlights the implication of the decisions for the maritime industry.

BRIEF FACTS

The Respondent commenced this action at the Rivers State High Court claiming, among other reliefs, the sum of N14,800,000.00 (Fourteen Million, Eight Hundred Thousand Naira only), (the equivalence of 38,845 US Dollars)[3] representing hire rentals of the houseboat Prince III. It was the Respondent’s case that it delivered the houseboat to the Appellant for the temporary use of the Appellant’s staff. After the delivery of the houseboat to the Appellant, the Appellant requested that the houseboat be upgraded to European executive standard. Pursuant to this

request, the Respondent claimed to have carried out further modification of the houseboat while the houseboat was in possession of the Appellant. Upon the completion of the modification, the Respondent alleged that the Appellant refused and or neglected to make payment for the hire of the houseboat. The Appellant denied the Respondent’s claims and contended that it did not take delivery of the houseboat because the Respondent failed to meet the delivery deadline and also because the boat did not meet the required standard.

At the conclusion of the trial, the High Court found as a fact that there was a contract between the parties involving the hire of the houseboat. The Court, among other reliefs, awarded in favour of the Respondent the sum of N8,800,000.00 (Eight Million Eight Hundred Thousand Naira), (the equivalence of 23,097 US Dollars) being the hire rentals of the houseboat. On appeal, the Court of Appeal upheld the decision of the High Court. The Appellant further appealed to the Supreme Court. One of the issues submitted for the consideration of the Supreme Court was whether the Respondent’s claim fell within the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court as to rob the High Court of Rivers State

the jurisdiction to entertain the suit. The Appellant referred to sections 251 and 272 of the Constitution and argued that the High Court of Rivers State did not have the requisite jurisdiction to entertain the suit. On its part, the Respondent argued that the High Court of Rivers State had the jurisdiction to hear and determine the suit as the suit was based on a simple case of debt owed by the Appellant to the Respondent which arose from breach of contract of hire of a houseboat and that the claim did not arise in the main nor touch on anything admiralty to oust the jurisdiction of the High Court of Rivers State. The Supreme Court held that the Rivers State High Court had the jurisdiction to hear the case.

Order via Legalnaija.com/shop

BASIS OF THE COURT’S DECISION

In arriving at its decision, the Supreme Court considered the provisions of section 251(1)(g) and 272(1) of the Constitution. Section 251(1)(g) of the Constitution provides as follows:

“Notwithstanding anything to the contained in this Constitution and in addition to such other jurisdiction as may be conferred upon it by an Act of the National Assembly, the Federal High Court shall have and exercise jurisdiction to the exclusion of any other court in civil causes and matters –

- any admiralty jurisdiction, including shipping and navigation on the River Niger or River Benue and their affluents and on such other inland waterway as may be designated by any enactment to be an international waterway, all Federal ports, (including the constitution and powers of the ports authorities for Federal ports) and carriage by sea.”

Section 272 of the Constitution provides that:

“Subject to the provisions of section 251 and other provisions of this Constitution, the High Court of a State shall have jurisdiction to hear and determine any civil proceedings in which the existence or extent of a legal right, power, duty, liability, privilege, interest, obligation or claim is in issue.”

The Court also considered 26 of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act, 1991 which defines a ship as “a vessel of any kind used or constructed for use in navigation by water, however it is propelled or moved.…”

The Supreme Court affirmed the finding of the High Court that the transaction between the parties was a hire of the houseboat. Muhammed J.S.C who delivered the lead judgment regarded the transaction as “a simple contract and not an admiralty or maritime matter. This is because…the action filed before the trial court is for the recovery of accrued and unpaid hire rentals for a houseboat let to the appellant by the respondent and damages for breach of the contract.” The Court held further that the fact that a houseboat comes within the meaning of a ship under section 26 of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act cannot convert an agreement for hire of houseboat into an admiralty agreement. The mere fact that a ship is involved in a simple contract does not automatically make that simple contract a subject for jurisdiction in admiralty matters. The Court concluded finally that “This case of a simple contract of debt recovery is within the civil jurisdiction of the Rivers State High Court and it properly assumed jurisdiction on the matter.”

COMMENTARY

With all due respect to the Supreme Court, the decision under review is contrary to the express provisions of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act which defines in detail the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court. Section 1(1)(a) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act specifies that the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court includes the jurisdiction “to hear and determine any question relating to a proprietary interest in a ship or aircraft or any maritime claim specified in section 2 of this Act.” Section 2 of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act enumerates several claims that fall within the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court. In particular, section 2(3)(f) of the Act provides for “a claim arising out of an agreement relating to the carriage of goods and persons by a ship or to the use or hire of a ship, whether by charter-party or otherwise.”[4] These provisions of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act are very clear and unambiguous. It is settled law that where the words used in a statute are plain and unambiguous, the courts are enjoined to give the words their ordinary and natural meaning without embarking on a voyage of discovery.[5]

The Respondent’s claim in the decision under review, being a claim relating to the hire of a houseboat, falls squarely within the purview of section 2(3)(f) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act, and as such falls within the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court. Surprisingly, the Supreme Court did not consider the provisions of sections 1(1)(a) and 2(3)(f) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act in arriving at its decision, even though the Appellant relied on these sections in its argument.

The Admiralty Jurisdiction Act which defines the scope of the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court provides for different types of agreements and transactions that are within the admiralty jurisdiction. Some of these agreements and transactions are mortgage of a ship, carriage of goods, supply of goods or materials to a ship for its use or maintenance, provision of services to a ship, shipbuilding, repair of ship, and so on.[6] All these are based on contracts. The decision that the Federal High Court lacks the jurisdiction to hear and determine any claim based on simple contracts has the effect of stripping the Federal High Court of its admiralty jurisdiction as most of the items of claims enumerated in section 2 of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act can only be actualized by means of contracts.

It is particularly worrisome that in June 2020, the Supreme Court in CRESTAR INTEGRATED NATURAL RESOURCES LIMITED V. SHELL PETROLEUM DEVELOPMENT COMPANY OF NIGERIA LIMITED[7] held that “There is no aspect of breach of contract, be it a simple or complex contract, that the Constitution in Section 251(1) thereof, confers jurisdiction on the Federal High Court to adjudicate on.”

The law is clear that a court is competent to exercise jurisdiction whenever the subject matter of the claim is within the jurisdiction of the court. It is the subject matter of a contract and not the existence of the contract that determines the jurisdiction of a court. Using the existence of a contract as a test for determining jurisdiction, instead of the subject matter of the contract, has the effect of stripping the Federal High Court of the admiralty jurisdiction duly conferred on it by the Constitution.

The obvious implication of the decision under review is that ship owners, charterers, seafarers and consignees have lost the opportunity to commence admiralty actions at the Federal High Court where the action is based on contract.

For further enquiries, please contact:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| JACOB FAMODIMU jacob.famodimu@advocaat-law.com |

|

|

| LAZARUS KALU Lazarus.Kalu@advocaat-law.com |

|

|

| GLORY OGUNGBAMIGBE glory.ogungbamigbe@advocaat-law.com |

|

|

|

[1] (1987) 1 NWLR (Pt. 49) 212; (1987) LPELR-SC 139/1985.

[2] ONUORAH Vs. KADUNA REFINING & PETROCHEMICAL CO. LTD (2005) LPELR-2707 (SC).

[3] At the exchange rate of 381 Naira to 1 US Dollar

[4] Underlining for emphasis

[5] See Aromolaran v.Agoro (2014) 18 NWLR (pt. 1438) 153

[6] See section 2 of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act

[7] SC/765/2017 delivered by the Supreme Court on 5th day of June 2020

by Legalnaija | Sep 2, 2021 | Uncategorized

BACKGROUND

The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended) confers admiralty jurisdiction on the Federal High Court[1]and Maritime labour claims particularly claims by a master or a member of the crew of a ship for wages, falls within the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court.[2] Recent decisions from the Federal High Court and the National Industrial Court derogates from the admiralty jurisdiction exclusively conferred on the Federal High Court by the Constitution. By these decisions, the Federal High Court lacks the jurisdiction to hear and determine any matter pertaining to unpaid wages of seafarers on the basis that the Constitution has cloaked the National Industrial Court (NIC) with the exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine all labour and employment matters. Thus the payment or non-payment of crew wages is deemed a labour matter for adjudication by NIC.

One of the advantages of commencing an admiralty action in rem at the Federal High Court is the ability of the Claimant to arrest a vessel as a pre-judgment security for his claim. Claims for seafarer’s wages constitutes a maritime lien on the relevant vessel and as such the vessel may be arrested in an admiralty action in rem as a pre-judgment security for the claim of such wage. The unfortunate consequence of these decisions that claims for seafarer’s wages do not fall within the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court is that the Claimant loses the opportunity to arrest vessels as pre-judgment security for maritime labour claims.

The case under review examines the basis for the removal of maritime labour claims from the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court and highlights the implications of the decision for the maritime industry.

BRIEF FACTS

The Respondents commenced an admiralty action in rem at the Federal High Court against the vessel MT Sam Purpose and the Owners of MT Sam Purpose claiming, among other reliefs, the sum of $53,097.51 US Dollars being crew wages owed them in respect of services rendered on board the vessel. By way of a Motion Ex Parte, the Respondents sought and obtained an order of arrest of the vessel as a pre-judgment security for their claims. The Appellant applied to the Federal High Court to set aside the order of arrest of the vessel and to strike out the suit on the basis that the Federal High Court lacked the jurisdiction to entertain claims for crew wages. The Federal High Court dismissed the Appellant’s application. Dissatisfied with the decision, the Appellant appealed to the Court of Appeal. One of the issues for determination before the Court of Appeal was whether payment of crew wages fell within the admiralty jurisdiction of the Federal High Court. The Court of Appeal held that the Federal High Court lacked the jurisdiction to entertain any claim relating to payment of crew wages as the Constitution has vested the National Industrial Court with the exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine all labour related matters, inclusive of maritime labour matters and crew wages.

BASIS OF THE COURT’S DECISION

The Court of Appeal considered the constitutional provisions conferring admiralty jurisdiction to the Federal High Court. The Court also considered section 2(3)(r) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act, 1991 which empowers the Federal High Court to entertain claims for payment of crew wages. The Court also examined the provisions of the Constitution as to the exclusive jurisdiction on the National Industrial Court in respect of labour and employment matters.

Section 251(1) (g) of the Constitution provides as follows:

“Notwithstanding anything to the contained in this Constitution and in addition to such other jurisdiction as may be conferred upon it by an Act of the National Assembly, the Federal High Court shall have and exercise jurisdiction to the exclusion of any other court in civil causes and matters –

- any admiralty jurisdiction, including shipping and navigation on the River Niger or River Benue and their affluents and on such other inland waterway as may be designated by any enactment to be an international waterway, all Federal ports, (including the constitution and powers of the ports authorities for Federal ports) and carriage by sea.”

This constitutional provision is further elaborated upon by the scope of the admiralty jurisdiction set out in sections 1 and 2 of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act. Section 2(3)(r) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act particularly conferred jurisdiction on the Federal High Court to hear and determine claims “by a master, or a member of the crew, of a ship for wages.”

It is on the basis of these provisions that the Federal High Court exercises jurisdiction over payment of crew wages.

The case under review also relied on sections 254C (1)(a) and (k) of the Constitution which provides as follows:

“Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 251, 257, 272 and anything contained in this Constitution and in addition to such other jurisdiction as may be conferred upon it by an Act of the National Assembly, the National Industrial Court shall have and exercise jurisdiction to the exclusion of any other court in civil causes and matters-

- relating to or connected with any labour, employment, trade unions, industrial relations and matters arising from workplace, the conditions of service, including health, safety, welfare of labour, employee, worker and matters incidental thereto or connected therewith;

- relating to or connected with disputes arising from payment or nonpayment of salaries, wages, pensions, gratuities, allowances, benefits and any other entitlement of any employee, worker, political or public office holder, judicial o1Ticcr or any civil or public servant in any part of the Federation and matters incidental thereto.”

The Court of Appeal after considering these provisions held that the purport of section 254C of the Constitution was to confer on the National Industrial Court exclusive jurisdiction over employee wages and other labour-related matters, including seafarer’s wages. The Court declared section 2(3)(r) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act null and void for being inconsistent with the provisions of section 254C of the Constitution which the court held to be “clear and unambiguous.” The Court in its decision recognized that section 251(1)(g) of the Constitution vested exclusive jurisdiction on the Federal High Court over admiralty matters which includes claims for crew wages. However giving the literal meaning to the provisions of the constitution in sections 251 and 254c the intent was clear as to the vesting of jurisdiction over crew wages to the NIC.

COMMENTARY

Until the Supreme Court overrules the decision of the Court of Appeal or the Court of Appeal overrules itself, the implication of the decision of the Court of Appeal in the case under review is that:

- Seafarer’s can only resort to the National Industrial Court to enforce all labour-related matters including maritime labour claims as the Federal High Court no longer has the powers to entertain such claims;

2. The law regards crew wages as a maritime lien on a vessel.[3] Maritime liens arise by operation of law and are independent of the seafarer’s employment contract. Prior to the decision of the Court of Appeal in the case under review, maritime liens were enforceable against the vessel in an admiralty action in rem in which the Claimant had the opportunity to arrest the vessel as a pre-judgment security for his claim. Following the decision of the Court of Appeal, claims for payment of crew wages may have lost its status as a maritime lien; and

3. Admiralty actions in rem are commenced against the vessel itself apart from its owners. Now, Claimants would have to bring an action against their employer for payment of crew wages. With claims against the vessel no longer feasible as a result of this decision, Claimants would no longer be able to obtain an order of arrest to secure their claim as the National Industrial Court does not have any admiralty jurisdiction.

Order via legalnaija.com/shop

The decision under review has settled the jurisdictional tussle between the Federal High Court and the National Industrial Court over crew wages. Prior to the Court of Appeal decision, there were conflicting decisions in this regard. In ASSURANCE FOREINGEN SKULD V. MT CLOVER PRIDE[4] the Federal High Court held that the National Industrial Court is imbued with the jurisdiction to deal with actions for unpaid crew wages. In the case of AKUROMA DAWARIKIBU STEPHEN V SEATEAM OFFSHORE LIMITEd,[5] the National Industrial Court in assuming jurisdiction over the subject matter held that the provisions of section 2(3)(r) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act and section 254C of the 1999 Constitution (as amended) are in conflict. As such, section 2(3)(r) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act was declared void to the extent of its inconsistency with section 254C of the 1999 Constitution. In MOE OO & 26 ORS V MV PHUC HAI SUN,[6] the Federal High Court held that the National Industrial Court does not have jurisdiction in matters relating to unpaid crew wages.

The law is now settled and the claims for unpaid crew wages are exclusively within the jurisdiction of the National Industrial Court. Shipowners, charterers and crew members are to take note of this latest development.

[1] See section 251(1)(g) of the Constitution.

[2] See section 2(3)(r) of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act of 1991.

[3] See section 67 of the Merchant Shipping Act of 2007 and section 5 of the Admiralty Jurisdiction Act.

[4] Suit No. FHC/L/CS/ 1807/2017

[5] Akuroma Dawarikibu Stephen v Seateam Offshore Limited Suit No. NICN/PHC/124/2017 (unreported) decided by the National Industrial Court, Port Harcourt judicial division on February 24, 2020, Per Hamman J.

[6] Suit No. FHC/CS/L/592/11 (unreported) delivered by the Federal High Court, Lagos Judicial division on June 20, 2014, per Tsoho J

by Legalnaija | Aug 31, 2021 | Uncategorized

This book deals with entertainment as a complex of industries, and the products, events, and experiences that those industries produce. The types of entertainment this book primarily (though not exclusively) focuses on are films, music, sports, broadcast media and other artistic expressions (fine, visual, and performing arts). Entertainment law is a specialised area of law that deals with facilitating the creation and distribution of entertainment, such as film, musical works, literary works, performances, visual art, broadcast media, sports, etc.

The book, proudly the first published work on entertainment law in Nigeria is the definitive resource and a textbook for practitioners and persons working in the entertainment industries of film, music, sports, broadcast media and the arts; including entrepreneurs and investors in these industries.

Michael Dugeri, the author, is a Senior Associate in the commercial law firm of Austen-Peters & Co, where he focuses his practice on entertainment, technology, corporate, intellectual property, and general business transactions. He is also a public speaker and facilitator at events that provide capacity building for artists, writers, directors, and producers in the media and entertainment industries.

To order your copy for N25,000, simply log on to the Legalnaija online book store via www.legalnaija.com/shop, or speak to one of our sales representatives on 09029755663. We offer International Delivery as well as Payment On Delivery for buyers in LAGOS only.

by Legalnaija | Aug 30, 2021 | Uncategorized

As with other fundamental rights in Chapter IV of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (CFRN), the guarantees in Section 37 -40 are subject to the omnibus limitation in Section 45(1) which excuses any law passed to abridge the right where such laws can be ‘’reasonably justifiable in a democratic society in the interest of defence, public safety, public order, public morality or public health; or for the purpose of protecting the rights and freedom of other persons”. This provision is consistent with international instruments such as Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union which permits similar derogations.[1]

Implicit in Section 37 of the CFRN are two fundamental tests for justifying derogations. The first is objective, and the second is subjective. These are:

- Is the derogation “in accordance with law”? and

- Is the law “justifiable in a democratic society”?

This principle was upheld generally in the judgement of the Supreme Court in INEC v. Musa.[2] With specific reference to telecommunications and ICT, the Court of Appeal in Okedara v. A.G Federation upheld the provisions of Section 24 of the Cybercrime Act, 2015 which prohibits dissemination of indecent content through computer and/or telecommunications systems and held that the provision does not violate the provisions of Sections 36(12) and 39 of CFRN.[3]

Essentially, any law which seeks to abridge the privacy right (for legitimate public interest) must trace legislative authority to, and derive its validity from Section 37, CFRN. Similarly, such abridgement can only be done by a subsidiary instrument if the main legislation provides clear legal basis and authority for such abridgement.

Key Issues in Net Neutrality and Telecoms Regulation

From a telecoms regulatory perspective, two key issues arise. These are the issue of content regulation and access (tariff) regulation.

- Content Regulation (Censorship) and Net Neutrality: the pertinent question is whether there should be any limitation on the nature of traffic to be carried by licensees, and who decides such limitations (if any)?

The basic principle of net neutrality is Internet Freedom, and it is generally recognised as a human right. By implication, this right is constitutionally guaranteed in Nigeria by Section 39(1) of the Nigerian Constitution which protects the right of every person to “freedom of expression, including freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart ideas and information without interference“ and Section 39(2) which protects the right to “own, establish and operate any medium for the dissemination of information, ideas and opinions“.

This freedom does not however preclude regulation, which empowers institutions of government or the private sector to guide action towards the achievement of predetermined goals pertaining to safety, national security and/or social and economic well-being (including the avoidance of legal liability). In this regard, Regulatory instruments would include Laws, Bye-laws, and Codes of Conduct/self regulation instruments and contracts[4]. Regulation thus defined can be contrasted with censorship, through which governments restrict access to content which they object to on political, cultural or other grounds, regardless of actual impact.

Many governments however assert a right to censor access and/or content. This right is typically justified by the need to protect security interests.[5]

Censorship models include physical disconnection of internet connections, URL filtering, blacklisting specific Internet Addresses and/or Domain Name Servers, and deep packet inspection. Censorship could be done occasionally (as with the shutting down of internet connectivity during elections and

during periods of national upheavals like the “Arab Spring”); or on a permanent basis (such as China’s “great firewall” and North Korea’s “country intranet” through which they filter content that can be accessed within their respective jurisdictions).[6]

The regulatory imperative is empowered by Section 39(3) of the Nigerian Constitution which approves “any law that is reasonably justifiable in a democratic society to prevent “the disclosure of information received in confidence, maintaining the authority and independence of courts or regulating telephony, wireless broadcasting, television or the exhibition of cinematograph films” or imposing restrictions on public officers and for security purposes.

In this regard, the NCC has developed an Internet Industry Code of Practice which provides far reaching provisions on net neutrality and internet governance.[7] The Code recognises the standards of transparency and non-discrimination, prohibits throttling, blocking, preferential and/or data prioritisation. It however permits “zero-rating” in limited circumstances, as well as “acceptable traffic management practices”, i.e. those carried out to preserve the “integrity and security of the network, of services provided via that network, and of the terminal equipment of internet users”; to prevent or manage network congestion; or to comply with a law, court order or regulatory obligation.[8] Provisions are also made for data protection, data security as well as the protection of minors and other vulnerable dependents.[9]

The Code reflects the position that as far as governments are concerned, regulation will continue to be justified by security and other national interests such as the need to protect cultural and other values; to ensure safe use for children and other vulnerable population segments; to encourage healthy usage; protect against cybercrime, preserve cultural identity, and develop local content. Censorship on the other hand is difficult to justify if it results in denying citizens the constitutional protections of being able to freely share ideas.[10]

- Access regulation – the impact of Tariffing Policies on Net Neutrality: this issue is particularly important given that an overwhelming majority of Nigerians access the internet through mobile devices.[11] In principle, discriminatory pricing restricts access and would contravene net neutrality requirements. In practice however, two scenarios are presented:

- Scenario 1: Charging more for OTT services: in the absence of strict net neutrality requirements, operators could carry out deep-packet inspection and charge higher tariffs to consumers for data-heavy content (such as video streaming or video calling) or content from selected services. This discriminatory pricing would help in cost recovery and can help minimise the regulatory asymmetry which now works in favour of OTTs. Alternatively, networks can prioritise certain services and share network costs with the OTT providers with whom they have sharing arrangements. This would of course have implications on competition, consumer rights and service quality.

- Scenario 2: Providing Special OTT packages – operators have sought to stay competitive by launching special packages which charge lower data tariffs for selected OTT platforms.[12] Essentially, these are discriminatory tariffs, since the consumer pays more for using similar platforms/services not covered by these preferential arrangements. Jurisdictions like India and Canada have barred such practices as anti-competitive.[13]

A combined reading of the above-cited provisions of the NCA, the Internet Industry Code of Practice and the VOIP Regulations leads to the conclusion that under Nigeria’s regulatory regime, full net neutrality is required, and both scenarios above are unacceptable. However, scenario (2) above is very common.[14]

It should be noted that the United States officially ended its net neutrality policy in June 2018 through the decision not to renew the 2015 Open Internet Order which protected net neutrality. It remains to be seen how this would impact the practice in other jurisdictions. [15]

Finally, we should note that users are often able to use Virtual Private Networks (VPN) to overreach censorship and/or internet restrictions by either masking their internet protocol addresses, encrypting data to hide their communications from government monitors and also to gain access to blocked content and/or websites. So far, there is no blanket ban on the use of VPN in Nigeria as is the case with North Korea and similar jurisdictions.

For further enquiries, please contact:

LATEEF BAMIDELE lateef.bamidele@advocaat-law.com

LINDA ASUQUO linda.asuquo@advocaat-law.com

ROTIMI AKAPO rotimi.akapo@advocaat-law.com

[1] Instrument 2000 O.J. (C 364) 1 (Dec. 7, 2000). See Art. 32(1)

[2] Independent National Electoral Commission v. Musa (2003) 3 NWLR (Pt.806) 72

[3] Okedara v. A.G Federation (2019) LPELR-47298(CA)

[4] All the major internet portals have terms of usage which restrict usage in one form or the other to protect the platform from legal liability for libel, intellectual property infringement, cyberattacks and other hostile action whilst also protecting other users’ legal rights.

[5] The attitude is typified by the statements recently ascribed to the Ethiopian Prime Minister, that “Internet is not water; internet is not air. Internet is a very important. However, if we use it as a revolution tool to incite others to kill and burn, it will be shut down not only for a week, but longer than that… for sake of national security, internet and social media could be blocked any time necessary… as long as it is deemed necessary to save lives and prevent property damages, the internet would be closed permanently, let alone for a week…”see report by Abdur Rahman Alfa Shaban, ‘Twitter backlash after Ethiopia PM’s internet ‘not water or air’ threat’, Africanews.com (online, 3, August 2019) < https://www.africanews.com/2019/08/03/twitter-backlash-after-ethiopia-pm-s-internet-not-water-or-air-threat/ > accessed on 4 August 2019.

[6] The easy dissemination of “fake news”, “anti-government propaganda”, “hate speech” and the notable sensitivity of African governments on these issues led to “at least 12 instances of intentional internet or mobile network disruptions in 9 countries in 2017, compared to 11 in 2016”, and the shutdowns are getting more sophisticated, “targeting smaller groups of people and locations” see Abdi Latif Dahir, ‘There was some good news but also plenty of bad with Africa’s digital space in 2017’ Quartz, December 22, 2017 < https://qz.com/1162891/there-was-some-good-news-but-also-plenty-of-bad-with-africas-digital-space-in-2017/ > accessed on 31 March, 2020; a contentious draft Bill (the Protection from Internet Falsehoods and Manipulation and other Related Matters Bill, 2019, SB 132) is pending before the National Assembly on the issue – it passed its second reading in November 2019.

[7] The draft was issued in June 2018 – text available at <https://www.ncc.gov.ng/documents/809-draft-code-of-practice/file > accessed on 22 October 2018.

[8] NCC’s Draft Internet Industry Code of Practice, Paragraph 3.7

[9] See generally Paragraph 4 and 5 of the draft Guidelines.

[10] Arguably, the increasing fragmentation of the internet due to divergent privacy regimes and the race to control the provision and adoption of 5G technology may well influence Nigeria’s policy, legal and regulatory regime.

[11] NCC data as at the end of August 2020 shows a total of 149,338,969 mobile internet users (GSM): 10,834 for fixed wired and 422,433 for VoIP users respectively – see current data on the Industry Statistics page on the NCC website at < https://ncc.gov.ng/stakeholder/statistics-reports/industry-overview > last accessed on 6 October, 2020 (note that data on the website is regularly updated).; as noted elsewhere, VoIP here also includes the VoLTE standard.

[12] Examples are the Facebook Lite provided by Airtel Nigeria and the “Social bundles” provided by virtually all the other operators – the former allows free access to a stripped-down version of Facebook while the latter allows users access to certain social media platforms as a “free” or much cheaper add-on to their voice or data subscriptions.

[13] See the report by Brian Jackson, ‘Nigeria faces net neutrality crisis as carriers consider banning Skype’, itworldcanada.com (online, February 22, 2017) < https://www.itworldcanada.com/article/nigeria-faces-net-neutrality-crisis-as-carriers-consider-banning-skype/390884 > accessed on 23 February 2017; it should be noted that Section. 3.6 of the NCC’s draft Internet Industry Code of Practice would permit “zero rating” on a range of subjective criteria, i.e. if it “furthers the objectives of the Act, particularly Section. 1 (c), and policy objectives of Universal Access contained in the National Information and Communications Technology Policy 2012 and the Nigeria ICT Roadmap 2017 – 2020, in accordance with the provisions of the Competition Practice Regulations 2007, and with the approval of the Commission”.

[14] Regulators may need to reflect this pragmatic market dynamic in future regulation by providing a guiding framework to prevent abuse – a case-by-case approach does not make for regulatory certainty.

[15] It is notable that one of the reasons given for the repeal is the FCC Chair’s belief that removing net neutrality restrictions (and thereby allowing carriers to decide what traffic to carry and how) will encourage network investments by those carriers: Ajit Pai ‘Our job is to protect a free and open internet’ (op-ed piece by the FCC Chairman) CNet.com (online, June 10, 2018) < https://www.cnet.com/news/fcc-chairman-our-job-is-to-protect-a-free-and-open-internet/ > accessed on June 11 2018; the reversal was unsuccessfully challenged in court by 22 States.

by Legalnaija | Aug 23, 2021 | Uncategorized

Question of the Week

Hello, my name is Amaze Oma, founder of The Mma Fashion Line. Five years ago, I had an idea to add a new design to our summer collection. I named the design ‘Dove Neck’. After 4 months of drawing up styles and dresses of ‘Dove Neck’, my attention was drawn to an identical design by Lara’s Fashion House. Because of the jeopardizing effect this could have on our new design, we quickly contacted Lara’s Fashion House to desist from using and even releasing the design.

Surprisingly, Lara’s Fashion House disagreed, claiming that they could use it as they pleased. According to them, no fashion designer or tailor could rightly claim original creation of any styles and that if Lara’s Fashion House didn’t use it another tailor would definitely use it. They described our original as “mere recognition on paper”. This is bad news and it’s going to be a serious drawback to my summer launch. I don’t even know how Lara’s Fashion House got hold of our Dove Neck design. A friend told me I should have registered the design. But I didn’t know about these things. I regret not doing so. Please help me. Don’t tell me all my hard work and effort to protect my design is all a waste. My summer launch is at the verge of jeopardy. Do I have a chance? Please help me!

Answer

Fashion designs qualify as artistic works under the Nigerian Copyright Act. Consequently, they are eligible for copyright protection. But because ‘Dove Neck’ is not only an artistic work but a model or pattern intended to be multiplied by an industrial process, copyright protection does not extend to such use.

What do originality and definite medium of expression really mean?

Originality and expression of this originality in a definite medium are vital for copyright protection. Section 1(2) of the Copyright Act requires both in any work of copyright.

To enjoy copyright, Dove Neck need not have been registered. What is essential is that the design is original and fixed in a definite medium of expression.

For The Mma Fashion Line, originality means you must have expended sufficient efforts in making the Dove Neck design unique in order to give it an original character. Apart from originality, you must have fixed the design in a definite medium of expression. This means you must have expressed your original design in any definite form from which it can be perceived.

Therefore, since you created the design originally and it has been expressed by applying it to a dress, your design meets the two requirements. Even if you only had a mere recognition on your sketchbook and somebody stole it and used it in any way, including publication in any medium, it would still have resulted in copyright infringement. Hand-drawn design sketches or sketches produced by Computer-Aided Design (CAD) technology may be protected by copyright.

Having said that, copyright protection does not extend to artistic works if, at the time the designs were made, they were intended by the author to be used as a model or pattern to be multiplied by any industrial process.

Intellectual property is broadly divided into copyright and industrial property. This is why once a work of copyright is industrially applied, copyright protection does not apply anymore. At this point, industrial property does.

This is why section 1(3) of the Copyright Act does not extend copyright protection to artistic works if at the time they were made, they were “intended by the author to be used as a model or pattern to be multiplied by any industrial process.”

Therefore, as long as you intended to use Dove Neck as a model or pattern to be multiplied by any industrial process for The Mma Fashion Line, copyright does not apply. Yes, the Copyright Act practically killed the joy of fashion designers with this restriction. This is why as a fashion designer, you must look beyond copyright for protection.

By registering Dove Neck as an industrial design, you enjoy protection, regardless of mass production.

According to the Patents and Designs Act, a design is simply a combination of lines or colours or both, and any 3-dimensional form, whether or not associated with colours. Before a design can be registrable under the Act, it must be new and it must not be contrary to public order or morality {section 13(1)(a) and (b) of the Act}.

Based on the requirements above, if before application for registration, the ‘Dove Neck’ design has been revealed or made available to the public, by description or use, it shall not qualify as a new design. Unless you were oblivious of ‘Dove Neck’ design’s availability to the public, and you are able to prove this to the satisfaction of the Registrar of Patents and Designs, you may have lost your design. Also, exhibition of your design in an officially recognized fashion exhibition does not amount to “making [it] available to the public”, as long as the registration for industrial design is made not more than 6 months after the exhibition.

Since you didn’t reveal your ‘Dove Neck’ design to the public nor participate in an exhibition, it is eligible for registration as an industrial design, subject to newness.

Therefore, an industrial-design registration is the safest option for protecting your new models and patterns for fashion designs. It’s not automatic as copyright is, but it’s worth the investment.

As a last port of call, you may consider registering the brand name and logo as trademark and incorporate it into all your designs.

While an industrial-design registration protects the 3-D design, trademark protects your brand—name, logo, etc. This is what leading brands like Luis Vuitton, Gucci, Ralph Lauren, and others do. With trademark protection, you are not only protecting your market but also making yourself qualified to obtain legal remedy under the Trademarks Act should any person infringe on your trademark.

The option of copyright would have been available to you but for the reason that you intend to mass-produce your ‘Dove Neck’ as a model or pattern at the time of creation. This negates a copyright under the Copyright Act.

Although advanced measures for the protection of fashion designs exist in some foreign jurisdictions, sadly it is not same for Nigeria. In Nigeria, industrial design and trademark are your best bet.

Consider contacting an IP lawyer or law firm for professional advice and assistance.

IP ABC

by Legalnaija | Aug 22, 2021 | Uncategorized

On Monday 16th August, 2021, President Mohammadu Buhari signed the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) 2021 into law thereby replacing the Petroleum Industry Bill 2020. The oil and gas industry is a highly important part of the nation’s economy as it contributes about 60% of the total income of the nation. Therefore, it is only pertinent that national matters or anything pertaining to this industry be taken very seriously. What does the assenting of this new law signify? The dawn of a new era in the way oil and gas business is run in Nigeria.

The PIB is a combination of various Nigerian laws on petroleum i.e. the monetization and protection of the nation’s oil and gas resources and it has gone through several changes since its creation in 2008. One of the benefits of a new Petroleum Industry Bill include increased investment opportunities as the industry will be more regulated and thus attractive due to these changes. Another major benefit of the enactment of a new PIB is to ensure that every official and institution in the industry fully understands their responsibilities and are able to fulfill their roles in such a way that the NNPC becomes a highly lucrative commercial endeavor. The creation of a new set of petroleum laws an imperative action that is long overdue because the old laws were no longer environmentally compliant and most of them were not globally competitive.

The move towards enacting this new law is a laudable one even though there is really no provision on transitioning from the current usage of fossil fuel to clean renewable energy as seems to be the global trend.

Below are some of the key changes that have been made to the Petroleum Industry Bill 2021:

- Establishment of a fund for the exploration of unassigned frontier basins across the country such as Chad Basin, Sokoto Basin and Benue Trough. This fund is 30% of Profit from oil and gas sale made by NNPC Limited.

- Creation of the National Petroleum Corporation Limited to be incorporated under the Companies and Allied Matters Act within six months of the bill coming into effect. The institution now has to work like any other organization aimed at making money with the exception that ownership of shares is held by the Ministries of Finance and Petroleum on behalf of the vested owner, the government. NNPC automatically becomes NNPC Limited with all the interests, assets and liabilities transferred to the new company and all its employees consequently becoming its workers too.

- Creation of a Host Communities Development Trust Fund to be registered under the Companies and Allied Matters Act after 12 months of the commencement of the bill.

- Regulation of the Oil and Gas industry by The Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Comission (“The Commission”) and The Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (“The Authority”).

- Management of Environmental and Gas Flare depending on the size of operation and the risk involved.

- Creation of New Licenses which are the Petroleum Prospecting Licence, Petroleum Mining Lease and Petroleum Exploration Licence.

- Voluntary agreement between buyers and sellers on gas prices even though regulation is still a function of The Authority.

- The Commission and The Authority are both to be run by a Governing Board who will handle general administration and other policy-related matters.

- Permission of companies with refining license as well as international credibility for trading in petroleum products to import any product shortfall that goes unmet by local refineries.

- Limitation of the discretionary powers of the Minister of Petroleum to grant and revoke licenses. This power is now subject to the recommendations of The Commission.

- Creation of other funds such as Environmental Remediation Fund based on size of operations, Decommissioning/Abandonment Fund based on periodic appraisals and Midstream and Downstream Gas Infrastructure Fund which is slated at 0.5% of wholesale price of petroleum and natural gas products sold in Nigeria.

- Calculation of Royalty based on price and production even though Nigerian refineries have preferential royalty rates.

In conclusion, it is obvious that the changes that have been made to the Petroleum Industry Bill are much needed in keeping with the times and current world practices. The provisions contained in the new Bill as drafted by the National Assembly are quite commendable but like all newly enacted laws, we cannot begin to guage how effective the laws will be if we have not implemented or enacted them. Other than that, the motives behind the creation of the bill and the enactment itself promise a very exciting development in the oil and gas industry.

References

Ajayi Adewale (2021) Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) 2021 – A Game Changer? KPMG Nigeria. Available at https://www.mondaq.com/nigeria/oil-gas-electricity/1093178/petroleum-industry-bill-pib-2021–a-game-changer-update

Thomas David (2021). What you need to know about Nigeria’s Petroleum Industry Bill. African Business Blog. Available at https://african.business/2021/07/energy -resources/what-you-need-to-know-about-nigerias-petroleum-industry-bill/

Bakare Majeed (2021) What you need to know about proposed law to regulate Nigeria’s oil industry. Premium Times blog. Available at https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/472172-pib-what-you-need-to-know-about-proposed-law-to-regulate-nigerias-oil-industry.hyml

Olajumoke Ogunfowora

@AOCSolicitors

www.aocsolicitors.com.ng

by Legalnaija | Aug 22, 2021 | Uncategorized

Repatriation: To send back to one’s own country.

Repatriation has been defined as the act of making amends for a wrong. According to Black’s law dictionary, 9th edition 1325. It is a compensation for an injury or wrong especially for wartime damages for a breach of international obligation. It seeks to mitigate harm caused because of a loss of opportunity and compensate the claimant for the loss caused.

Restitution, on the other hand is quite similar to repatriation as they both involve the idea of restoration but it is more concerned with recovery as opposed to compensation for the loss suffered. The relief granted to the original owner of the property is usually measured in view of the loss suffered by the owner and not the unjust enrichment of the other party.

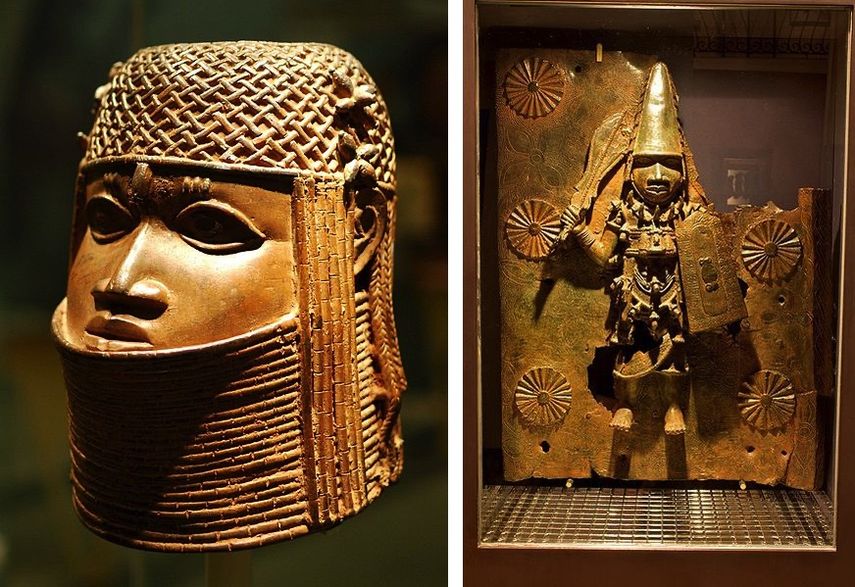

Nigeria has recently been involved in negotiations for the return of its cultural items/artworks acquired during the colonial era through force of arms and deception. In 2014, the Boston Globe reported an arrangement by the Museum of Fine Arts to return eight (8) Nigerian artifacts that were illegally taken to the United States some decades ago.

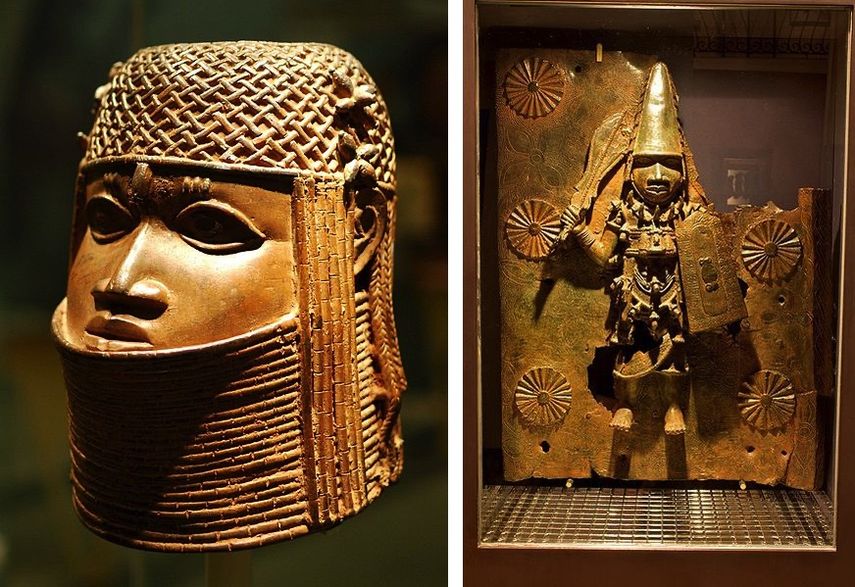

The Benin bronzes which were carted away by the British Government in their punitive expedition of on Benin City in 1897 are on the verge of being repatriated back to Nigeria from Germany. Germany has the second-largest collection of Benin bronzes in the world and has agreed to return over two thousand bronzes back to the country to be housed in a new museum in Benin City, Nigeria by 2022.

With respect to cultural heritage, repatriation is a key concept that must be practiced when unjust enrichment occurs to or loss is suffered by one party.

Cultural heritage as defined by the United Nations is the mirror of a country’s history, thus lying within the very core of its existence, since it represents not only specific values and traditions, but also a unique way a people perceives the world.

Cultural heritage is incredibly vital in any community or nation in that it is not just ornamentally significant but also economically relevant in the global antiquities market. Therefore, the current move by the German government to restore the Benin Bronzes to the rightful owners seems to be a highly commendable one and to be emulated by other nations with respect to illegal possession of another country’s cultural heritage.

A few laws and international conventions have been enacted which seek to prevent prohibit and prosecute illegal importation of cultural artifacts. These include the 1970 UNESCO Convention (on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property); The 1954 Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property also known as the Hague Convention; The 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illicitly Exported Cultural Objects. The only thing that seems to be an issue is the fact that the laws are not retroactive and do not therefore ratify any transaction make before the enactment of the conventions. Other sources of international law with respect to cultural heritage are the Resolutions of the United Nations General Assembly and agreements between nations or regions.

There are however some arguments in existence that seek to validate the lack of repatriation of lost artworks to their original homes. The first is the idea that cultural heritage belongs to all mankind because each group of persons makes cultural contributions to the culture of the world, therefore, it does not matter the current location of the property as long as it is preserved and put on a platform that the whole world can see it. This belief is called cultural internationalism and is predicated on the poverty or ignorance of the owner nations to properly preserve or treat the fragile art works from the effects of natural decay and damage. The result is usually that the nation in possession of the property is usually unjustly enriched from the property at the expense of the rightful owners and that it would be highly difficult for the people who own the cultural artifact to have access to it compared to the country that has taken it.

The second argument is based on cost, specifically litigation cost. Depending on how valuable the cultural property, it is argued that it would cost a lot of money and resources for the source nation (especially if it’s a developing nation) to see to it that the artifacts are brought back. With respect to litigation, it would be relatively expensive to fund and almost impossible to get witnesses to prove what goods were stolen or where exactly they were stolen from seeing as the expatriation occurred somewhere around the 19th century.

As it stands now, there is an ongoing controversy in Nigeria as to where the received Bronze artifacts are to be returned. The Oba of Benin, the Edo state government and the Federal Government of Nigeria have all laid claims to the Benin Bronzes. Key lessons can be taken from the case of Peru v. Johnson, the government of Peru claimed that it was the legal owner of the artifacts seized by the United States Customs Service. The court held that there was no direct evidence that the items came from what is now modern day Peru because the Peruvian culture as at the time of the seizure spanned not only Peru as it is now but also some of the territory that is now Bolivia and Ecuador.

In conclusion, the move to repatriate African art is a highly commendable one by the German government but it should be noted that the exact location for the artifacts to be returned to is crucial to the entire repatriation process as seen in the aforementioned case otherwise the repatriation would end up being forfeited due to the disputing claims from various parties.

References:

- Klesmith, Elizabeth A. (2014) “Nigeria and Mali: The Case for Repatriation and Protection of Cultural Heritage in Post-Colonial Africa, “Notre Dame Journal of International Cooperative law”. Vol 4. Iss. 1, Article 1.

Available at http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjicl/vol4/iss/1

- Larry Mayor Alton Jones, Repatriations, Restitution & Transitional Justice

Available at: http://issi-media.stanford.edu/evnts/6421/85-repatrations,-restitution,-andtransitional-justice.pdf

- Black’s Law Dictionary, 9th edition 1325

- Government of Peru v. Johnson, 720 F. Supp. 810 (C.D. Cal. 1989)

- Chitty on Contract, London Street & Maxwell, 1632 (2004)

@AOCSolicitors

info@aocsolicitors.com.ng

www.aocsolicitors.com.ng

by Legalnaija | Aug 13, 2021 | Uncategorized

What is an Affidavit?

An affidavit is a sworn written statement voluntarily made by a person called a deponent affirming something to be true and which is administered by a person legally authorized to do so. It is an official statement that contains a verification made under oath or affirmation with the understanding that if the statement is found to be untrue or misleading, the deponent could be on penalty of perjury. Affidavits are typically used in courts as evidence or proof. Affidavits are typically used in courts as evidence or proof. The general contents of an affidavit are contained in Section 90 of the Evidence Act.

What is an Affidavit of Change of Name?

An affidavit of change of name is a sworn written document declaring that a person has changed their name from and has discarded the old name. This could be a modification in spelling of a name, an addition of a new name or change of surname which is especially particular to newly married women. Essentially, anybody can change their name as long as they are up to 18 years of age which is the legal age in Nigeria. Note that a change of name would be invalid if it with the intention to commit a crime or to escape a financial obligation or for any other illegal reasons.

How to Use an of Affidavit of Changeof Name

This affidavit is mostly used in the event of a marriage or a divorce. Once an affidavit is sworn to and notarized, the next step for anyone intending to change their name is to make a public declaration in a national newspaper in order to give general notice to anyone concerned. The next step is to inform the relevant authorities and to effect the changes immediately. These relevant authorities include bank officials and other relevant bodies specifically but notlimited to the ones that involve personal identification e.g. passports, national identity cards, driver’s license, etc.

As a newly-wed woman or a recent divorcee who has changed their name to a new one, you need to formally inform the court of this development and to do that, you would need an affidavit. Do not bother yourself with the rigorous details of creating an affidavit from scratch,you can simply download a customizable template on www.legalnaija.com.

by Legalnaija | Aug 13, 2021 | Uncategorized

What is an Affidavit?

An affidavit is a sworn written statement voluntarily made by a person called a deponent affirming something to be true and which is administered by a person legally authorized to do so. It is an official statement that contains a verification made under oath or affirmation with the understanding that if the statement is found to be untrue or misleading, the deponent could be on penalty of perjury. Affidavits are typically used in courts as evidence or proof. Affidavits are typically used in courts as evidence or proof. The general contents of an affidavit are contained in Section 90 of the Evidence Act.

What is an Affidavit of Loss?

An affidavit of loss is a legal statement declaring that a security or certificate or license or any original document has been lost, destroyed, mutilated or stolen.

How to Use an Affidavit of Loss

This document can be used in situations when you lose an important document such as a certificate of stocks and bonds, or more commonly your identity card to a fire, theft, flood or any other situation. Immediately you notice that any of the aforementioned items or your original documents has been misplaced or damaged, it is expedient that you file an affidavit of loss.

Filing an affidavit of loss is necessary in order to prevent someone else in possession of the original document i.e certificate of the stocks and bonds to lay claims to it as the original owner. You must present an affidavit of loss if you are going to be indemnified or have your certificate replaced by the security issuer.

The affidavit of loss should describe the security that has been lost with one or more documents evincing your ownership of the said security. It must give a detailed explanation of the circumstances that led to the loss as well as verify your identity as the owner.

You also need to file a police report in addition to the affidavit as supporting documentation. In order to make it legally binding, the affidavit must be sworn at a court before a commissioner for Oaths or be notarized by a notary public.

If ever any of your personal items or documents gets lost or stolen, you can save yourself the stress of finding where to procure an affidavit of loss by simply downloading a customizable template on Legalnaija.com