by Legalnaija | Nov 8, 2025 | Blawg

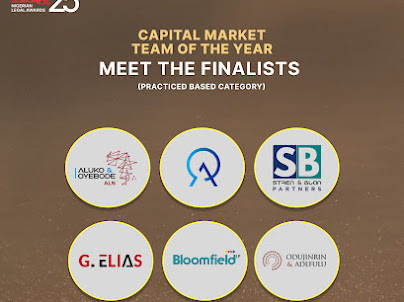

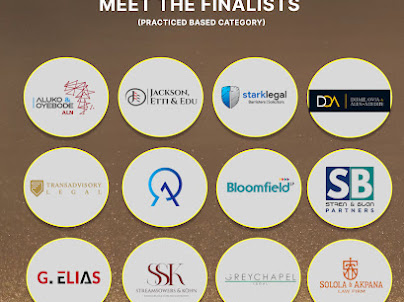

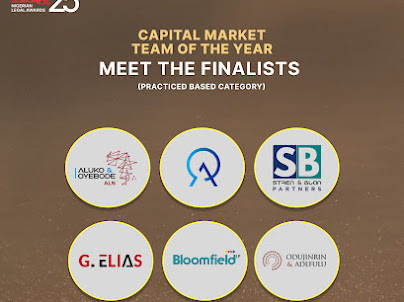

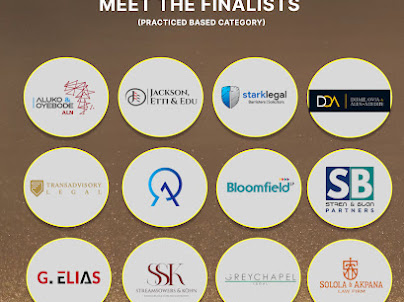

The Nigerian legal community is gathering in style and substance for the prestigious ESQ 25 Nigerian Legal Awards, a celebration of brilliance, impact, and innovation across the legal profession. From seasoned firms to rising stars, this year’s finalists reflect the dynamic evolution of law in Nigeria.

Some of the categories of awards include;

Immigration Team of the Year

CSR Team of the Year

Law Firm of the Year (Large Practice)

Law Firm of the Year (Mid Practice)

40 Under 40: Rising Legal Stars

The ESQ 25 Nigerian Legal Awards are more than accolades—they’re a mirror reflecting the strength, diversity, and promise of Nigeria’s legal landscape. Legalnaija is proud to spotlight these trailblazers and celebrate the stories behind the success.

Stay tuned for exclusive interviews, behind-the-scenes moments, and more coverage from the awards.

#Legalnaija #ESQ25Awards #NigerianLaw #LegalExcellence #40Under40 #CSRLeadership #ImmigrationLaw #LawFirmOfTheYear

by Legalnaija | Nov 5, 2025 | Blawg

Introduction

It is common knowledge amongst Nigerians that the nation’s legal system is often more beautiful on paper than in practice. In many respects, the Nigerians laws remains a figment of ideal imagination-sound in reality but weak in execution. The law governing taxation is one of such areas plagued by this reality. Perhaps this is because Nigeria’s tax laws are wholesome adoptions of frameworks developed in more advanced economies, without sufficient adaptation to local realities. Or perhaps the concept of taxation is complex to many Nigerians.

Whatever the reason, there’s no denying that taxation plays a critical role in national development and revenue generation. Yet, Nigeria continues to struggle with effective enforcement and compliance. In recent years, the country’s tax-to-GDP ratio has been alarmingly low hovering around 5-6% a figure far below the African average.[1] This persistent shortfall prompted repeated amendments to key tax legislations such as the Companies Income Tax Act, Personal Income Tax Act, Stamp Duties, and Capital Gains Tax Act under what was known as -the Decentralized tax system or the old tax regime.

Despite the several amendments, the tax to GDP ratio still very low. Recognizing the the urgent need for reform, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s administration, initiated a comprehensive framework. This culminated in the enactment of four new tax reform laws signed on the 26th of June, 2025[2] namely:

- Nigeria Tax Act (NTA)

- Nigeria Tax Administration Act (NTAA)

- Nigeria Revenue Service Act (NRSA)

- Joint Revenue Board Act (JRBA)

While the Nigeria Tax Act serves as the substantive law defining what tax exist and how they are charged, the Nigeria Tax Administration Act governs how taxes are assessed, collected and enforced. The Nigeria Revenue Service Act establishes the new Nigerian Revenue Service (NRS) in charge of administering the provision of the Act, while the Joint Revenue Board Act strengthens coordination across all tiers of government through a more robust Joint Revenue Board (JRB).

Undoubtedly, the new tax regime deserves commendation for its clarity and structure- at least in theory. It attempts to resolve the long-standing problem of multiple taxation across federal, state and local levels. Yet one critical question remains:

Will this new regime truly improve Nigeria’s tax-to-GDP ratio, or merely beautify a system whose root problem is still the manner in which taxes are paid and collected?

This article explores the issues of backdoor tax payments in Nigeria. It examines the gap between how tax payments ought to be made and how they are actually made in practice, investigates the causes of these informal payment channels and proposes practical, context driven solutions to address this systemic challenge.

Definition of Terms

To properly understand the concept of backdoor taxation, it is necessary to define two core terms-tax and backdoor taxation as used in this context.

Tax

A tax is simply a compulsory contribution imposed by government on individuals and entities for the purpose of generating revenue to fund public expenditure. it is not a voluntary payment, donation or gift; it is a legal obligation backed by law.

Charles E. MeLure Jr. defines tax broadly as “a compulsory charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a government organization in order to collectively fund government spending, public expenditures, or as a way to regulate and reduce negative externalities”[3]

Backdoor taxation

The word backdoor connotes secrecy, illegitimacy, and circumvention. In the context of this article, Backdoor taxation refers to instances where taxpayers pay legitimate taxes but through unauthorized or unofficial channels. This could mean settling and paying directly into tax officer’s personal account, cash payments without receipts or remittances made outside government approved systems such as Remita, or official revenue service portals.

In simpler terms backdoor taxation occurs when tax is paid the wrong way. The taxpayer fulfils their obligation in theory, but the payment fails to reach government coffers. Consequently, the payment cannot be verified, recorded or properly accounted for turning compliance into waste.

The idea of tax as a means of Public funding for government- for the greater good-is a noble, even genius. But to many Nigerians, it feels more like a financial burden or yet another corruption scheme by the government. As a result, citizens have resorted to various backdoor tax payments and in some cases, total evasion.

A common misconception among Nigerians is that taxation is not prominent is this part of the world but some borrowed culture from the Europeans-A myth based on lack of information and knowledge. In truth, taxation has been integral to nation building, during pre-colonial era traditional rulers acted as tax administrators, levying contributions on farm produce and trade goods[4]

Today taxation remains a statutory duty with the force of law, forming a key part of Nigeria’s revenue base. However, the misconception persist-not entirely without reason. It is still possible for a Nigerian to live their entire life without knowingly paying tax, or to have paid certain forms of tax (such as Stamp duties, PAYE) and still be ignorant about it.

Understanding what taxation truly means and how it has evolved from a legitimate system of public contribution into a practice often manipulated through unofficial routes helps shed light on the reality of backdoor taxation in Nigeria today.

Backdoor Taxation in Practice

In practice, taxation in Nigeria is largely depends on the tier of government involved. Yet one thing is common across all tiers: no filing is made to accompany payment, (underlining mine for emphasis). Tax payers simply pay without filing.

The observations discussed here are not based on speculation or hearsay but on firsthand experience and consistent field realities.

Federal Government & State Governments

At the federal and state level, tax payers typically remit tax without filing any documentation to disclose income, expenditure, profit or loss. Many assume that since the Act already prescribes a percentage for remittance, they can simply pay the amount.

While this informality may sometimes favour tax payers-allowing them to underpay due to lack of transparency in assessment it is equally disadvantageous to honest taxpayers who assume tax must simply be paid without filing as they lose the opportunity to deduct allowable expenditure from their tax liability.

Under this category, payment depends on the type of tax payers generate an invoice through Remita, pay into the Sigle Treasury Account (TSA) with the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) or State Internal Revenue Service (SIRS) and then drop a copy of their payment details with the respective office.

Another prominent way tax is paid in here is that many tax payers deliberately ignore their tax liabilities until tax officials visit their premises. During such visits, officials demand documents such as Tax Clearance Certificate for the previous year, Tax Identification Number (TIN), receipts of past payments, pay slips, PAYE remittance records (depending on the type of tax) etc.

At that point, the tax liability is typically negotiated and settled below the actual amount due, with payments made directly into the private accounts of the tax officials. In some cases, the taxpayer visits the revenue office and pays into the account of a preferred official-with or without a receipt.

Despite this informality, such taxpayers are often recorded as “compliant” for the year. No further notices are issued, and no follow up visits are made to verify remittance or ensure accuracy.

Local Government

At the local government level, the situation takes an even less formal turn.

Local government agents routinely visit business and residential premises with demand letters requesting arbitrary amounts for various levies and purposes. In some states as such as Ekiti, Ebonyi and Zamfara, taxpayers are accustomed to this practice that they approach the local councils directly to make payments-often preemptively, or to avoid harassment.

Upon receiving a demand letter, taxpayers are expected to negotiate what they can afford with the officials who served the notice. Once a fair amount is agreed upon, the payment is made directly into the private account of the serving officer and a receipt is issued immediately.

Alternatively, the taxpayer may choose to visit the local government office, negotiate and pay into the private accounts of the staff there. However, it is often considered “safer” to pay the field officers who deliver the demand letters, since they tend to return repeatedly until payment is made.

In a meeting with the Warri South Local Government Council head to requested the official account details of the council in order to make direct payment. the explained that paying directly into the local government account would mean paying the full, ridiculous sum stated in the demand notices, without any room for negotiation and that the procedure to pay same is very stressful and complicated. More revealing, he explained that since the government does not adequately pay the staff responsible for serving tax demand notices, they instead engage locals to deliver those notices and allow them keep part of the collections as compensation-remitting only a fraction to the council as tax.

If there’s a backdoor tax payment the question naturally flows-What’s the right way to pay tax?

TAX PAYMENT PROCEDURE IN NIGERIA

In paper tax can either be filed and paid by:

- Gathering all required documents such as Tax Identification Number, Annual Return, evidence of income, allowable expenditure etc. depending on the type of tax

- Download and fill the applicable tax (Form C08A, C08B, C)8C, or C08D)

- Login to the FIRS self-filing system to file tax returns

- Ensure that you obtain a receipt or acknowledgement of your records[5]

Causes of Backdoor Tax Payment

The first thing that comes to mind here is corruption, but the question that follows is: what is the cause of corruption? Non-patriotism? Perhaps. Yet, as flimsy and funny as it may sound, the mother of corruption that gives birth to many other forms of corruption in Nigeria including backdoor tax payment is convenience.

Most taxpayers in Nigeria do not know the proper procedure for paying tax-from filing to payment. they either understand the electronic nor the manual methods of filing and payig tax. many also lack the basic accounting skills to compute tax records for filing. Hence, Nigerians often opt for the most convenient method: paying directly into the private accounts of tax officials.

At first, the taxpayer does this in the hope that the official will eventually remit the money into the treasury Single Account. But over time, it becomes more convenient because it allows taxpayers to pay less than their actual liability.

Even Nigerians who understand electronic filing and payment may still resort to backdoor payment due to poor internet connectivity, system downtime, or technical failures on official platforms.

Other causes of backdoor tax payment and evasion

- Un-skiled Tax Officials – As earlier discussed, many Nigerians do not fully understand the concept of taxation or how it operates in practice. Ironically, many of these individuals are employed in the FIRS and SIRS or now NRS not base on competence but through federal character, tribalism, and favouritism. Sadly, this weakens professionalism and muddles the entire tax landscape. Also, some tax officials intentionally exploit tax payers ignorance to solicit bribes.

- Non registration of Taxpayers: A large number of taxable persons in Nigeria have not registered or obtained a Tax Identification Number (TIN), making enforcement difficult and tax records incomplete.

- Lack of technological tools for compliance: In the 21st century, technology is used globally to make tax administration efficient. But in igeria, public institutions-especially in the tax sector-remain largely analog. It is shameful that in this digital age, tax officials still visit organizations one by one to check compliance, requesting receipts that they themselves issued.

Ideally, technology should enable tax authorities to pull up every Tax Identification Number and automatically generate a list of organizations, businesses and individuals who have defaulted in remittances, triggering penalties or prosecution.

- Lack of motivation to pay tax – Tax as we know, is an imposition by government to fund public projects such as road construction, and building or renovations of schools, hospitals, courts, etc. However, when taxpayers do not see visible-impact and instead witness blatant embezzlement of public funds they become discouraged and demoralized. This lack of trust leads may to cheat the system by paying only a fraction of their liability through the backdoor, or by evading tax altogether.

- Non-enforcement of tax Laws– tax evasion is a crime and like every crime, it will persist until government actively enforces the law. Until the system begins to sanction offenders consistently, many taxpayers will continue to evade tax, believing that the enforcement system is weak or even dead.

IS THE NEW TAX REGIME A SAVIOUR TO BACKDOOR TAX PAYMENT/TAX EVASION?

While we must appreciate the new regime for simplifying the Nigeria’s tax system by unifying taxes across the tiers of government- thereby reducing the tax burden on taxpayers, we must not forget that the major reason behind its creation was Nigeria’s low tax-to-GDP ratio,[6] which ranked among the lowest in Africa in 2024. The new regime was therefore introduced not necessarily to address backdoor payments or tax evasion, but primarily to improve revenue generation.

This brings us to the crucial question:

Will the new tax regime truly improve Nigeria’s tax-to-GDP ratio, or will it become another toothless bulldog?

To answer this, our main focus must be on the Nigeria Tax Administration Act (NTAA), 2025 which serves as the primary legislation for enforcing the substantive law.

To be forward, the Nigeria Tax Administration Act did not expressly envisage backdoor tax payments; however, certain provisions particularly those under Chapter Four (4) could potentially address backdoor taxation and evasion if the law were to meet the realities on ground.

Key Provisions and Their Gaps

- Failure to register for Tax (Section 4)

The Act provides that a taxable person who fails to register for tax will pay fine of N50,000 for the first month of default and subsequently pay N25,000 for continued default until registration is completed.[7] However, the practical gap lies in identifying unregistered taxable persons in the first place. In reality, Nigeria’s tax enforcement primarily affects those who are visible-such as banks, oil companies and salary earners of banks and oil companies-while many self-employed persons and small businesses remain outside the net.

- Failure to File Returns and proper book keeping (Section 101& 102)

The Act further provides that a taxable person who fails to file tax returns, or who files incomplete or false returns, shall pay an administrative penalty of N100,000 for the first month of the failure and 50,000 for subsequent failure.[8]

In theory this seem strict, but in practice, the system is not designed to detect defaulters effectively-because many tax-payers self-access and remit payments without proper filing. However, this may work well for corporate taxpayers already in the system. But not for small business owners.

Section 102 of the Act mandates every taxable person to keep proper business records and produce them when requested. Failure attracts N10,000 fine for individuals and N50,000 for companies. This section is not implemented in reality, because small Nigerian traders keep no books at all. Even educated professional rarely keep structured records it’s too much work for most Nigerians to compute records, hence they look for easier alternatives.

- Failure to use Fiscalisation or Approved Technology (Section 103 & 104)

provides for refusal to use fiscalisation system by tax official and not using the approved electronic system for accounting records the act provides that taxable person that refuses use of electronic systems like fiscalisation machines after 30 days of receiving the notice, will be liable to pay N1,000,000 for the first day of refusal and N10,000 for each day of refusal. When the taxable person fails to use the approve technology the person will pay a fine of N200,000 plus 100% of tax he should have paid and interest at the Central Bank.[9] This provision is not applicable in reality, if it were many tax payers must have spoken about a time tax officer tried installing a technological device in their premises or fined them for non-compliance. Enforcement may be limited to large retailers, fuel stations and formal enterprises.

- Failure to Remit or Self-Account for Tax (Section 107)

The Act provides that a taxpayer that fails remit tax by the 21st of every month will pay the unremitted amount, 10% annual penalty, interest at CB rate, and possible 3 years imprisonment.[10] While this is a powerful anti-corruption, enforcement is still weak as NRS (as the case maybe) must rely on audits, or whistleblowers to detect non-remittance. Also, tax authority rarely prosecutes for non-remittance

- Failure to comply with Notices/Supply Information (Section 108)

While Section 108 of the Act prescribe daily fine of N100,000.00 per day for ignoring official notices and failing to provide requested data. This is only enforceable to registered taxpayers. The provision is Worthless for unregistered or untraceable taxpayers.

- Offences by Authorized and Unauthorised Persons

Section 114 of the Act provides for offence by Authorized and Unauthorized Persons it provides thus:

“A person, whether or not appointed for the administration of this Act, any other tax law or employed in connection with the assessment and collection of a tax who-

- Demands or accepts any gratification from a taxable person in the performance of his functions under this Act or any other tax law,

- Withholds for his own use or otherwise any portion of the amount of tax collected,

- Renders a false return, whether orally or in writing, of the amount of tax collected or received by him

- Defrauds any person, embezzles money or otherwise uses his position to deal wrongfully with the relevant tax authority,

- Steals or misuses the documents of the relevant tax authority, or

- Compromises on the assessment or collection of any tax, commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine equivalent to 200% of the sum in question or imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or to both[11]

This section exists precisely because of Nigeria’s long-standing culture of embezzlement and abuse of official positions. Therefore, rather than merely copying OECD-style provisions from foreign models, the Act should have gone further to create practical Nigeria specific mechanisms for accountability.

For instance the Act could have provide specifically, the position of the Nigeria Revenue Service (NRS) staff responsible to collect tax payment. the NRS ought to also have an internal policy regulating the staff, stating what his report should contain, and there should also be an External Auditor to audit the NRS, on tax received, and report to the government.[12]

To answer our question, No-the new tax regime is not a saviour to the Backdoor tax settlement and payment, neither does the act cures tax evasion. In fact, it is important for one to note that the old tax regime, provides for penalties to tax evasion and backdoor payments as it is currently doing yet the reality of taxation did not reflect same.

Nigeria does not have problem with laws, it is one thing to have a law and another thing to ensure it is in practice otherwise the legal space will just be messy unless extra steps (though may seem petty) is taken to ensure our laws barks and bite. Hence to achieve this we must look at the remedies to backdoor tax settlement and payment and tax evasion.

PANACEA TO BACKDOOR TAX PAYMENT/TAX EVASION

- Technological Enforcement (Digital tax audit): Government should deploy a centralized electronic tax audit system directly linked to the National Identification Number (NIN) National Identification Cards, and Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) database. This will automatically detect unregistered taxpayers and ensure they comply with the Act by paying fine in accordance with section 100 of the Act.

- Flat rate tax for small and informal businesses: Local market women, artisans, and other informal businesses with no accounting knowledge should be taxed through a fixed, reasonable flat rate model payable quarterly or annually. This will encourage inclusion without overwhelming non-literate tax payers and reduces the temptation to negotiate payments through backdoor routes.

- Third party report: Nigerian government should invest in third party report system in ensuring that tax payers file truthful reports. The third-party report is simply NRS tracing digital trail of buyers and comparing same to what sellers file, or checking their banks through their financial reports or getting annual returns filed with CAC.

- Tax Literacy and Public Awareness Campaign: Many Nigerians pay tax unknowingly (e.g through Stamp duties or VAT) and thus underestimate their civic duty. A consistent awareness program led jointly by the Nigerian Revenue service (NRS) and the media can educate citizens on proper filing procedures, taxpayers rights and penalties for backdoor remittance.

- Independent Tax Oversight Committee: The NRS should be audited annually by an Independent Tax Oversight Committee (ITOC) comprising civil society accountants, ad judiciary representatives to ensure collected funds are properly remitted to the Single Treasury Account.

- Judicial and Legislative Reinforcement: Existing penalties in the Nigeria Tax Administration Act must be strictly enforced. Courts should treat tax evasion as economic sabotage, with expedited proceedings and mandatory recovery orders. The legislature should amend the Act to make electronic filing and fiscalisation systems mandatory for all taxable persons within two years of its commencement.

Conclusion

While the Nigeria Tax Administration Act, 2025 and related enactments represent bold attempt to sanitize the fiscal landscape, legislation alone cannot cure systemic rot. Backdoor tax payment thrives not merely because of weak law, but because of weak enforcement and low public trust.

Therefore, to truly strengthen Nigeria’s tax system and improve the tax-to-GDP ratio, reform must go beyond drafting; it must include digital enforcement, human integrity, and practical inclusion of small businesses. Until payment methods are streamlined, monitored, ad trusted, the Nigeria tax regime will remain clean only on paper.

[1] “Revenue Statistic in African 2024- Nigeria”, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) < https://www.oecd.org/cotent/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-sub-issues/global-tax-revenues/revenue-stastistics-africa-nigeria.pdf > accessed 20th October, 2025

[2] “Top 20 changes to know and top 6 things to do: The Nigerian Tax Reform Acts” < PWC: <pwc.com/ng/en/publications.the-nigeria-tax-reform-acts.html> Accessed 4th September, 2025

[3] Charles E. McLure Jr. “Taxation” Britannica

[4] Saviour Archibong ‘An Overview of Taxation I Nigeria’ Available at:https://download.ssr.com/24/03/18/ssrn_id4762979_code4809207.pdf?response-content-disposition=inlie&X-Amz-Security-Token=IQoJb3JpZ2VjEKX%2F%2F%2F%@f%2F% (Accessed 4th September, 2025)

[5] Federal Inland Revenue Service Available at https://ww.firs.gov.ng/company-income-tax?utm_source=chatgpt.comAccessed (5th September, 2025)

[6] International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2023 “Nigeria’s Tax Revenue Mobilization: Lessons from Successful Revenue Reform Episodes10/13/2025

[7] S. 100 of the Nigeria Tax Administration Act, 2025

[8] S. 101 of the Nigeria Tax Administration Act, 2025

[9] S. 103 and 104 of the Nigeria Tax Administration Act, 2025

[10] S. 107 of the Nigerian Tax Administration Act, 2025

[11] S. 114 (1) (a)-(e)

[12] S. 114 of the Nigerian Tax Administration Act, 2025

OKOROTE OZIOMA NWACHUKWU is a passionate litigation lawyer with a growing interest in taxation, tax reform and governance. Her interest in tax law is driven by a conviction that Nigeria can overcome its mounting debt not only through financial discipline but by giving earnest attention to taxation as a sustainable means of generating revenue and funding national development.

OKOROTE OZIOMA NWACHUKWU is a passionate litigation lawyer with a growing interest in taxation, tax reform and governance. Her interest in tax law is driven by a conviction that Nigeria can overcome its mounting debt not only through financial discipline but by giving earnest attention to taxation as a sustainable means of generating revenue and funding national development.

Although she ever set out to be a writer, Ozioma finds herself writing when it becomes necessary, when talking is no longer an option. This work reflects her deep sense of responsibility towards justice, structure and doing things the right way.

Beyond the courtroom, Ozioma is a firm believer in Christ and identifies with the Church of Christ. Her faith shapes her worldview and guides her choices. From her reasoning to her actions and inactions.

by Legalnaija | Nov 2, 2025 | Blawg

IMPLIED CONSENT UNDER NDPA-GAID: AN INNOVATIVE CONCEPT OR PROBLEMATIC ILLUSION? | Dr. Olumide Babalola

In March 2025, as part of their desire to extra-judicially simplify the Nigeria Data Protection Act 2023 (NDPA), the Nigerian Data Protection Commission (NDPC) issued a document titled the General Application and Implementation Directive (GAID – pronounced as “Guide”) containing explanatory guidance on the provisions of the NDPA. For the budding field of data protection, especially in Nigeria, the GAID ought to come in handy whenever the intention of the draftsmen or the regulator is interrogated. Still, when the provision of article 17(8) of GAID is considered, it is seen that the document does more than a mere explanation of the NDPA – it makes a ‘creation’ of some sort. In the succeeding paragraphs, I analyse my brief opinion on the concept of implied consent under article 17(8) of GAID

Inelegant drafting and logical impossibility

Although a commendable regulatory effort, rather than resolving the ambiguities in the NDPA, some provisions of GAID have created new problems owing to inelegant drafting. For context, article 17(8) provides that: “Nothing in this GAID shall prevent a data subject from giving a constructive or an implied consent to data processing in the following circumstances” (Emphasis mine) Interestingly, the provision above seeks to empower a data subject to “give” implied consent, but the idea is blatantly illogical and contradictory. The word ‘implied’ refers to something that arises by inference or operation of law, even though it is not expressly written or stated, hence, it cannot be ‘given’ by the data subject but inferred from certain facts.

“Giving” consent implies a positive, intentional act i.e something actively done by the person, but in this case, consent is inferred from a passive conduct without expressly stating the specifics. In other words, implied consent is not actively given, it is inferred from behaviour, circumstances, or failure to object. Providing that someone can “give” implied consent mixes two logically inconsistent ideas: one is active (i.e “gave”) and one passive (i.e “implied”). It gives a paradoxical impossibility, like suggesting someone “shouts silently.” The other problem with this provision is the suggestion that, once one attends a public event, the organisers have implied consent that images taken at the event may be used for a report of that event. This provision creates at least two potential problems. First, there is no definition of public event, hence everything is left to conjecture on what nature or type of event constitutes a public event.

Implied consent is unknown to NDPA

Consent is defined under section 65 of the NDPA as “any freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication, whether by a written or oral statement or an affirmative action, of an individual’s agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or to another individual on whose behalf he has the permission to provide such consent”

The definition above clearly signifies that consent must be “specific” “unambiguous” and by statement or ‘clear’ affirmation, whereas to imply means to suggest or indicate something without saying it directly and this is where the problem lies. While the NDPA prescribes consent to be specific and unambiguous, the GAID subjects the concept to inference, which now makes such consent debatable. In other words, the concept of informed consent is grounded in an assumption based on certain facts and circumstances but it is my respectful opinion that the draftsmen intended consent to be free from conjecture, especially by the use of “specific” and “unambiguous”.

Once parties begin to argue on the validity of consent, then its existence becomes doubtful and problematic, especially since NDPA provides that silence or inactivity does not constitute consent. The activity contemplated here must be such that it indicates the specific processing consented to but not an assumption that the data subject consents to all kinds of processing activities without spelling them out. For example, if a person attends an event where a notice is displayed that the event would be recorded and pictures taken would be used for promotional purposes, do this necessarily cover the subsequent (indefinite) storage and sharing with third-party vendors? This answer is not that straightforward, and that vitiates consent ordinarily.

Contemporary best practice

It is common knowledge that, from a data protection perspective, consent is inherently tricky, slippery and problematic, especially since it must be informed. Hence, once a controller cannot demonstrate that the data subject is duly informed of the specific processing activities they were consenting to, then consent is vitiated. Regardless of the position the NDPC wants to take on implied consent, it is important to consider the contemporary approach to this hydra-headed conundrum.

In 2020, the European Data Protection Board released their Guidelines 05/2020 on consent under Regulation 2016/679. Paragraph 168 of the document states that: “…the GDPR requires that a controller must be able to demonstrate that valid consent was obtained, all presumed consents of which no references are kept will automatically be below the consent standard of the GDPR and will need to be renewed. Likewise as the GDPR requires a “statement or a clear affirmative action”, all presumed consents that were based on a more implied form of action by the data subject (e.g. a pre-ticked opt-in box) will also not be apt to the GDPR standard of consent.” From the provision above, implied consent is not considered valid, especially where the controller is unable to demonstrate such informed consent

On what constitutes valid consent, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office clarifies that: “The idea of an affirmative act does still leave room for implied methods of consent in some circumstances, particularly in more informal offline situations. The key issue is that there must still be a positive action that makes it clear someone is agreeing to the use of their information for a specific and obvious purpose. However, this type of implied method of indicating consent would not extend beyond what was obvious and necessary.” (see https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/uk-gdpr-guidance-and-resources/lawful-basis/consent/what-is-valid-consent/) Here, the English regulator sounds a note of warning against reliance on implied consent, which does not usually make it clear to data subjects what specific purpose or processing activity they are consenting to.

Towing this line, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also frowns at implied consent which they considered ‘imposed’ as thus: “The knowledge or consent of the data subject is as a rule essential, knowledge being the minimum requirement. On the other hand, consent cannot always be imposed, for practical reasons. In addition, Paragraph 7 contains a reminder (“where appropriate”) that there are situations where for practical or policy reasons the data subject’s knowledge or consent cannot be considered necessary. (see OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data). Even across Africa, no country has notably adopted implied consent as part of its data protection framework; hence the global sentiment is to view the strange concept as an unreliable substitute for explicit, affirmative consent under modern data-protection laws.

Recommendations for improvement

To address the potential problems of implied consent, it is advised that article 17(8) of GAID is reviewed to either remove or qualify implied consent. It could be replaced with a more rights-respecting clause that recognises the validity of consent only when obtained through a clear, affirmative act by the data subject indicating agreement to the processing of personal data for specified purposes. If we must stick with implied consent, then it may be confined to extreme cases like emergencies or circumstances where a data subject is physically or mentally incapable of giving consent. For clarity, a demonstrable consent framework may be adopted by the NDPC to mandate controllers to keep verifiable records (logs, timestamps, digital signatures) of consent; enable simple withdrawal mechanisms; and periodically review consent validity for ongoing processing. Ultimately, to provide further guidance, the NDPC ought to issue standard consent templates and model privacy-notice clauses aligned with section 27 NDPA.

by Legalnaija | Oct 30, 2025 | Blawg

WELCOME ADDRESS BY PRESIDENT AND CHAIRMAN OF THE GOVERNING COUNCIL, INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED SECRETARIES AND ADMINISTRATORS OF NIGERIA (ICSAN), MRS. UTO UKPANAH, FCIS, AT THE 2025 ANNUAL SUMMIT OF THE LAGOS STATE CHAPTER OF ICSAN, HELD ON THURSDAY, OCTOBER 30TH, 2025 AT THE JEWEL AEIDA, LEKKI PHASE 1, LAGOS.

• The Vice-President of the Institute, Mr. Francis Olawale, FCIS;

• The Treasurer, Mr. Onyekachi Uko, FCIS;

• The Immediate Past President, Mrs. Funmi Ekundayo, FCIS;

• Past Presidents of ICSAN;

• Members of the Governing Council of ICSAN;

• The Chairman of the Occasion, Dr. Dayo Mobereola;

• Our Host, Ms Efosa Ewere, FCIS, Chairman of ICSAN, Lagos State Chapter;

• The distinguished Keynote Speaker, Professor Yinka Omorogbe, SAN;

• Invited Resource Persons

• Distinguished Fellows and Members of ICSAN;

• Media Partners;

• Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen.

It gives me immense pleasure to join you at the 2025 Annual Summit of the Lagos State Chapter of our great Institute, the Institute of Chartered Secretaries and Administrators of Nigeria (ICSAN).

This Summit represents yet another milestone in our collective journey towards deepening the culture of good governance, transparency, and professional excellence in Nigeria. It is not only a platform for intellectual engagement and knowledge-sharing but also a golden opportunity for networking, collaboration, and the building of stronger professional bonds among our members and with counterparts across various sectors.

The Lagos State Chapter, fondly regarded as “The Flagship Chapter”, plays a pivotal role. Over the years, the Chapter has continued to set high standards in professional engagement, event organisation, and membership drive. Its record of impact and consistency in promoting the Institute’s ideals of corporate governance and administrative excellence remains truly commendable.

The theme of the Summit, “Governance Redefined in a Business Environment: A Continuum or New Paradigms”, is both timely and thought-provoking. It invites us to critically examine the trajectory of governance practice to determine whether the evolution we are witnessing in today’s fast-changing world represents a logical continuation of existing norms or a paradigm shift that demands new mindsets and methodologies.

In today’s business landscape, shaped by technological disruptions, regulatory innovations, and socio-economic complexities, governance cannot be viewed through a static lens. We are experiencing a redefinition—a dynamic transformation—in the way organisations are directed, controlled, and held accountable. The governance professional is now expected not only to comply but also to strategically interpret and apply governance principles to enhance organisational resilience, stakeholder confidence, and sustainable value creation.

The relevance of this theme cannot, therefore, be overstated. Across industries, we are witnessing increasing demands for ethical leadership, transparency, inclusiveness, and adaptability. Global investors and regulators are equally raising the bar on governance expectations. It is indeed imperative for governance professionals to stay ahead of the curve and continually evolve in their thinking, skills, and practice.

This Summit thus provides a veritable platform for deep reflection and robust discourse on emerging governance paradigms, whether in corporate boardrooms, public sector institutions, or civil society organisations. We must ask ourselves: Are we still operating within traditional governance models, or are we embracing new frameworks better suited to the complexities of today’s interconnected, digitised world?

With new paradigms come challenges. Leaders and Boards must navigate complex regulatory environments, manage emerging risks and balance competing stakeholder interests. Governance today embodies both continuity and change. While the core principles of accountability, fairness, responsibility, and transparency remain immutable, their expression and application are being reshaped by emerging realities, digital transformation, ESG imperatives, stakeholder activism, and shifting socio-economic values. The governance professional must therefore remain agile, data-driven, and forward-thinking, while upholding integrity and accountability as timeless constants. I anticipate that this Summit’s discussions will illuminate those issues in detail and offer practical insights for adaptation.

Let me also specially commend the leadership of the Lagos State Chapter, ably led by Ms. Efosa Ewere, FCIS, and her hardworking team for their vision, diligence, and commitment. You have demonstrated the Chapter’s reputation for excellence and innovation.

Chapters are crucial tentacles for ICSAN’s outreach, visibility, and impact. Therefore, we will continue to provide the necessary support to enable them to thrive and sustain the momentum of professional advancement and institutional development for which ICSAN is known.

Our Chapters are not just administrative arms; they are vibrant hubs for professional interaction, community engagement, and policy advocacy. It is through their initiatives that the Institute’s ideals find expression in local contexts and in the everyday work of our members.

Please permit me to join the Chapter to thank Dr Dayo Mobereola for accepting to be the Chairman of this summit. I must also commend the Chapter for the careful selection of distinguished speakers and panelists, all accomplished professionals drawn from various sectors, academia, public service, private enterprise, and civil society. Having Professor Yinka Omorogbe, SAN, a renowned scholar, seasoned administrator, and respected voice in oil and gas law, as the Keynote Speaker further lends profound depth and credibility to today’s discourse. We eagerly look forward to her illuminating perspectives, as well as those of the eminent panelists who will contribute and enrich the discourse at this Summit.

ICSAN remains unwavering in its commitment to building capacity, strengthening governance consciousness, and equipping our members with relevant skills to navigate the evolving governance environment.

I encourage all participants to make the most of the opportunities this Summit presents, participate actively, ask questions, network meaningfully, and take away lessons that will enrich your practice and your organisations. Let us all continue to uphold ICSAN’s values: integrity, professionalism, service, and leadership. These are the cornerstones of sustainable governance.

Once again, congratulations to the Lagos State Chapter for hosting this Summit. May today’s deliberations broaden our perspectives, ignite innovative ideas, and strengthen our resolve to promote ethical governance and institutional excellence across all sectors. Together, let us continue to redefine governance, not only as a professional ideal but as a living practice that transforms institutions, enhances trust, and drives national development.

ICSAN! Greater Together!

God bless ICSAN.

God bless the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Mrs. Uto Ukpanah, FCIS

President/Chairman of the Governing Council

Institute of Chartered Secretaries and Administrators of Nigeria (ICSAN)

by Legalnaija | Oct 30, 2025 | Blawg

CHAIRPERSON’S WELCOME ADDRESS

The Honourable Chairman of today’s event, Dr. Dayo Mobereola, Director General, Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA);

The President and Chairman of the Governing Council, Mrs. Uto Ukpanah, FCIS;

The distinguished Keynote Speaker, Prof. Yinka Omorogbe, SAN, CEO/Founder, ETIN Power Limited; the Vice President, Mr Francis Olawale, FCIS , Honourary Treasurer,Mr Onyekachi Uko, FCIS, the Immediate Past President Mrs. Funmi Ekundayo,FCIS, Distinguished Members of the Governing Council Present, the Vice Chairman of the Chapter, Mr. Adebola Babatunde, FCIS, the Immediate Past Chairman, Mr. Olufemi Sokan, FCIS , Past Presidents Present, Past Chairmen of the Chapter present, Fellows of the Institute Present, Members of the Chapter, Members of the Institute and Non-members.Chairmen of other professional bodies present, Chairmen of other Chapters present, Executive Committee Members of the Chapter, Members of the Institute and Non-members, Gentlemen of the Press, Special Guests present, Ladies and Gentlemen. Captains of Industry, Corporate Executives, Esteemed Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen.

Good morning It is my honour and pleasure, as Chair of this Chapter, to welcome you all to the 2025 ICSAN Lagos State Chapter Annual Summit, It is a part of our Activities of the Corporate Governance Week introduced by this administration. Our Annual summit has become an annual gathering that continues to set the pace and realities of governance, ethics, and leadership across Nigeria’s corporate and public sectors.

It gives me immense pleasure to stand before you today as we convene once again to interrogate the evolving dynamics of governance under the theme, “Governance Redefined in a Business Environment: A Continuum or New Paradigms.” This theme is both timely and forward-looking. It challenges us to examine whether the governance principles we hold dear are merely continuing a legacy or transforming into new paradigms that better align with today’s realities.

This summit is not only a platform for dialogue but also a reflection of how far the Lagos State Chapter has come over the past year. Our Chapter has remained vibrant and active, hosting numerous impactful programs that embody our collective commitment to governance excellence and member development.

To our Chairman of the SUMMIT, keynote speaker, panelists, and thank you for lending your time, experience, and intellect to this summit. To our guests and delegates, your presence today is a testament to your shared commitment to advancing governance excellence in Nigeria. Delegates of this Summit who are lawyers will not only have a memorable time with our well-seasoned panellists but also have the advantage of earning the CPD points of the NBA ICLE by attending this event, so please the technical team will display the QR code at some point towards the end of today’s program.

As professionals, you would all agree that our world is changing rapidly, driven by digital transformation, sustainability imperatives, shifting stakeholder expectations, and socio-economic transitions. Governance, therefore, can no longer be confined to static rules and checklists. It must evolve into a living framework that adapts, anticipates, and leads.

As professionals, we must ask these questions:

• How do we sustain ethical leadership in a time of disruption or should I refer to them as shifts and not disruptions?

• How do we bridge traditional governance principles with emerging technologies, ESG imperatives, and new business realities?

• And most importantly, how do we redefine governance so it remains the bedrock of accountability, transparency, and sustainable growth?

You would all agree that governance today is not what it used to be. It is evolving constantly, and we are all somewhere between continuity and reinvention.

Gone are the days when governance simply meant having the right policies filed neatly in a cabinet and hoping no one ever needed to open them. Today, governance must be living, dynamic, and responsive — not just a compliance checklist, but a compass for strategic direction.

These are the conversations we will explore throughout this summit. Over the course of the day, we shall have engaging panel sessions around ‘Evolving Governance Models: Bridging Compliance and Strategic Alignment’ and ‘Adaptive Governance in the Age of Disruption: AI, Cybersecurity, and the Future of Corporate Structures’, drawing from diverse perspectives, from regulators and boardroom executives to thought leaders and governance practitioners.

our first session — “Evolving Governance Models: Bridging Compliance and Strategic Alignment” — will tackle that delicate balance between doing things right and doing the right things. How do we ensure that governance is not a bureaucratic burden but a value driver? I’m sure our panelists will help us navigate that fine line perhaps even better than some of our internal audit reports manage to!

Session 2 the panelist will interrogate the discussion “Adaptive Governance in the Age of Disruption: AI, Cybersecurity, and the Future of Corporate Structures” — we venture into the frontier where algorithms are smarter than some of our meeting minutes, and where the threats we face move faster than most board approvals.

These are not abstract issues; they are reshaping how we lead, how we make decisions, and how we safeguard trust. Governance, in this age, must not only adapt — it must anticipate.

What I find most exciting about today’s discussions is that we’re not just talking about rules and frameworks. We’re talking about people — about leadership, accountability, and resilience. Governance, after all, is not about control; it’s about confidence. It’s about creating the environment in which good decisions can flourish, even when uncertainty reigns.

As we embark on today’s sessions, I encourage everyone to listen, to challenge, to share — and to laugh when we can. Because if we can’t find a little humour in governance, we risk taking our policies more seriously than our purpose.

Before I close, let me express my heartfelt appreciation to God Almighty for this day, those in the Exco and Planning Committee, would understand why I must specially give honor to whom honour is due which is God Almighty, then to Our Chief Host Mrs Uto Ukpanah, FCIS for her continued support, and also our Immediate Past President Mrs Funmi Ekundayo, FCIS, I am privileged to have enjoyed the warmth and support of two powerful Presidents and with emphasis FEMALE PRESIDENTS of ICSAN and I am eternally grateful for all the love, I cannot even explain the kind of support I have enjoyed in this administration. They are a true testament of WOMEN supporting WOMEN and this is not me trying to patronize them.

I could never have put this week activities without the support of my Exco, a composition of very unique people with qualities that make us formidable, you all have been amazing, the Entire team of the Planning Committee led by Ms Folake Sadiq, ACIS,, the Subcommittee heads , Mr Osa Aiwerioghene, Mrs Laide Adeyemo, Mrs Blessing Choko and Ms Adeola Olumeyan and the FLAGSHIP committee led by Mrs Yetunde Braimoh, FCIS and the Welfare Committee led by my ever supportive Mr Temidayo Odulaja, FCIS, I sincerely show my appreciation for your support haven worked tirelessly to bring this summit and the entire activities of the Governance Week to life.

And, of course, to all of you — our delegates — thank you for being here, we welcome you once again. Let’s learn, engage, and perhaps even redefine governance together.

As we begin this summit, I urge everyone here in this room to engage fully, reflect deeply, and leave here inspired to drive change. Governance is not an end in itself; it is a living continuum, one that thrives on innovation, integrity, and inclusivity.

Let us, as governance professionals, continue to uphold the timeless values of transparency and accountability while boldly redefining governance for the future.

On behalf of the Executive Committee of the ICSAN Lagos State Chapter, I welcome you to the 2025 Annual Summit.

God bless ICSAN.

God bless ICSAN Lagos State Chapter.

God bless the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

by Legalnaija | Oct 27, 2025 | Blawg

In the fast-paced world of legal practice, small law firms often find themselves playing catch-up. Limited budgets, lean teams, and the constant hustle to attract clients can make growth feel like a distant dream. But what if there was a cheat code—an insider’s shortcut—to visibility, credibility, and client acquisition?

Enter the Legalnaija Directory: the digital power-up every small law firm needs.

Why Visibility Is Your Firm’s Superpower

Let’s face it—clients don’t flip through phone books anymore. They Google. They search online for lawyers who specialize in their needs, who are nearby, and who look credible. If your firm isn’t showing up in those searches, you’re invisible.

The Legalnaija Directory puts your firm front and center. It’s optimized for search engines, trusted by thousands of users, and tailored specifically for the Nigerian legal market. When potential clients search for legal help, your listing becomes your digital handshake.

What Makes the Directory a Cheat Code?

Here’s what sets the Legalnaija Directory apart:

- Targeted Exposure: Unlike generic directories, Legalnaija is built for lawyers, by lawyers. Your listing reaches people actively seeking legal services.

- SEO Boost: Your profile is indexed and optimized to appear in search results, giving your firm a competitive edge online.

- Professional Credibility: A polished, verified listing on Legalnaija signals trust and professionalism to potential clients.

- Networking Opportunities: Connect with other legal professionals, collaborate, and grow your referral base.

- Affordable Marketing: For a fraction of traditional advertising costs, you get year-round visibility.

Real Talk: Small Firms, Big Impact

You don’t need a skyscraper office or a million-naira marketing budget to make waves. What you need is strategic positioning—and that’s exactly what the Legalnaija Directory offers.

Whether you’re a solo practitioner in Ibadan, a boutique firm in Abuja, or a rising legal star in Lagos, the Directory levels the playing field. It’s your shortcut to being seen, being trusted, and being hired.

How to Get Listed

Getting started is simple:

- Visit app.legalnaija.com/

- Create your profile with your firm’s details, areas of practice, and contact info.

- Upload a professional photo or logo (if available).

- Hit publish—and watch your digital footprint grow.

In today’s legal landscape, visibility isn’t optional—it’s essential. The Legalnaija Directory is more than a listing; it’s your firm’s launchpad. Don’t wait for clients to stumble upon you. Be where they’re already looking.

Ready to unlock your cheat code?

Join the Legalnaija Directory today and let your firm shine.

by Legalnaija | Oct 19, 2025 | Blawg

Introducing the Legalnaija Lawyer Spotlight Series

At Legalnaija, we believe that the stories, insights, and expertise of Nigerian legal professionals deserve to be seen, heard, and celebrated. That’s why we’re proud to introduce the Legalnaija Lawyer Spotlight—a new interview series dedicated to showcasing the brilliant minds shaping the future of law, business, and innovation in Nigeria.

What Is the Lawyer Spotlight Series?

The Legalnaija Lawyer Spotlight is a curated interview series that highlights lawyers across various practice areas—from startup and tech law to litigation, commercial practice, and policy reform. Each feature offers a deep dive into the guest’s professional journey, their area of specialization, and the practical experiences that define their work.

Our goal is to provide valuable insights for aspiring lawyers, entrepreneurs, and anyone interested in the evolving legal landscape. Whether you’re a law student, a startup founder, or a fellow legal practitioner, this series will offer perspectives that inform, inspire, and connect.

Starting with Written Interviews

We’re beginning the series with written interviews, allowing our guests to share their stories in their own words. These interviews will be published on the Legalnaija blog and shared across our social media platforms.

In the coming weeks, we’ll expand the series to include audio and video formats, giving our audience even more ways to engage with the content and hear directly from the voices behind the practice.

Who’s Featured First?

Our first spotlight features a powerhouse in startup and tech law—someone whose work has shaped policy, empowered entrepreneurs, and redefined legal support for innovation in Nigeria. Stay tuned for the full interview.

Follow the Series

To keep up with each new feature, follow Legalnaija on social media and subscribe to our newsletter. We’ll be sharing interviews regularly, and we can’t wait to introduce you to the lawyers driving change across the country.

@Legalnaija

by Legalnaija | Oct 18, 2025 | Blawg

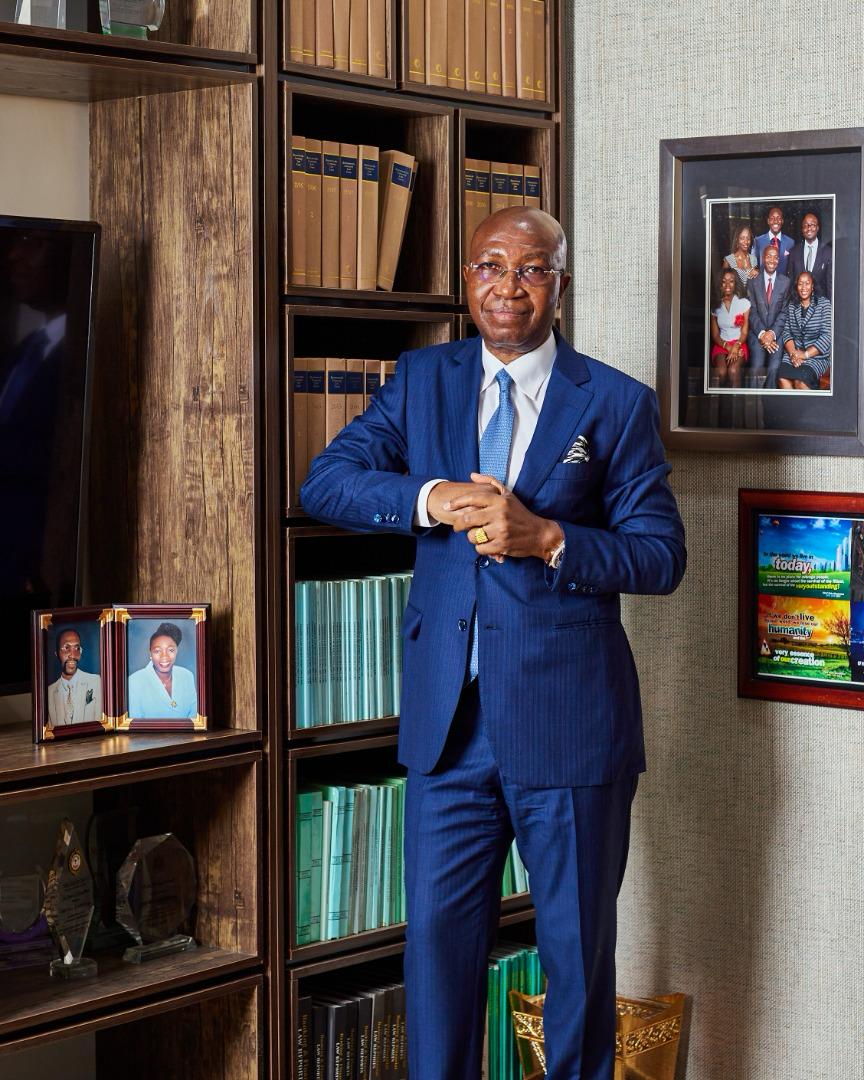

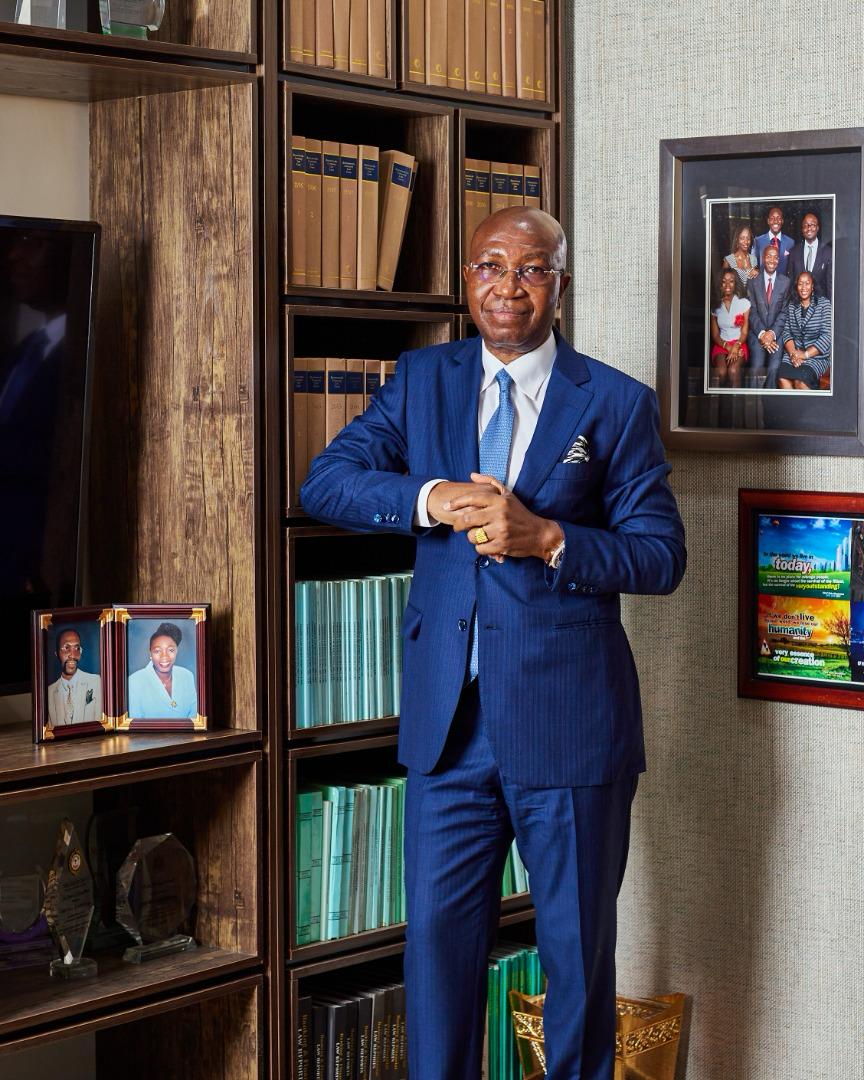

Today, Friday, the 17th of October 2025, another prestigious laurel was bestowed on a man of great accomplishment, honour and valor, the inimitable Chief ‘Wole Olanipekun CFR, OFR, SAN, by the Alumni Association of his Alma Mater, the University of Lagos (UNILAG).

I had the privilege of being in attendance at the 55TH Anniversary Awards & Recognition Dinner where the UNILAG Alumni Association conferred its most prestigious honour, the Platinum Alumni Award (Alumni Lifetime Achievement Award) on Chief Wole Olanipekun, in recognition of his outstanding contributions to the development of the University, the legal profession, nation-building, and his unwavering commitment to excellence, integrity, and service to humanity.

The award ceremony, which held at the Banquet Hall of the Eko Hotels, Victoria Island, Lagos State, brought together eminent personalities from across the legal, academic, political, and business communities to celebrate an illustrious alumnus of the institution whose legacy transcends generations.

A Beacon of Legal Excellence

Chief Wole Olanipekun, CFR, OFR, SAN, a distinguished alumnus of the University of Lagos Faculty of Law, has become a towering figure in the legal landscape of Nigeria and beyond. Since his call to the Nigerian Bar in 1976 and his elevation to the rank of Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) in 1991, Chief Olanipekun has continued to chart new frontiers in legal practice, jurisprudence, and advocacy.

He is widely regarded as one of Nigeria’s most formidable legal minds, having successfully handled landmark constitutional, electoral, and commercial cases. His courtroom mastery, scholarly depth, and principled stance on rule of law have set a gold standard in the profession.

Leadership, Legacy, and Service

Beyond the courtroom, Chief Wole Olanipekun has served Nigeria with distinction. In 1991, he was appointed Attorney General and Commissioner for Justice of Ondo State and served for two years. He was elected President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) in 2002 and served meritoriously till 2004. During his tenure as NBA President, he brought transformative leadership, advocating for judicial reforms, strengthening the independence of the Bar, and defending democratic principles at critical junctures in the nation’s history.

On 19 May, 2024, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu appointed Chief Olanipekun as the Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of the University of Lagos. He had prior to this appointment served as the Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of the University of Ibadan and also still currently serves as the Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of Ajayi Crowther University. As Chairman of Council in both University, Chief Olanipekun showcased his visionary commitment to higher education, institutional governance, selfless service and excellent philanthropic gestures. Under his stewardship, these universities recorded remarkable growth in infrastructure, academic reputation, and ethical leadership. At the University of Ibadan, he constructed and donated to the University a 350-capacity lecture theatre hall for the Faculty of Law. As Chairman of Ajayi Crowther University, he built the Vice Chancellor’s Lodge and other buildings, and constructed roads within the University.

A Philanthropist with a Heart for Education

Beyond philanthropic gestures to academic institutions, Chief Olanipekun is also a man of deep compassion and philanthropy towards humanity. Through the Wole Olanipekun Scholarship Board, he has offered scholarships to hundreds of indigent students, supported community development projects, and championed the empowerment of youth and women, particularly in his native Ikere-Ekiti and across Nigeria. In Ikere-Ekiti, Chief Olanipekun single-handedly built and donated a hospital with state of art facilities, an ultra-modern church and vicarage, a computer laboratory, a High Court building with a well-stocked library amongst several others.

He has consistently demonstrated that success is not just to be celebrated but shared, using his resources, network, and influence to uplift others and build a society anchored on justice and opportunity.

A Proud Ambassador of UNILAG

Chief Olanipekun has remained an active and passionate supporter of his alma mater. His career and values reflect the very ideals that the University of Lagos seeks to instill in its students, that is, critical thinking, intellectual rigour, ethical responsibility, and patriotic service. These values have earned Chief Wole Olanipekun several honours including National Honours of Officer of the Order of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (OFR) and Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (CFR). He is a recipient of several Honorary Doctorate Degrees. Recently, in July 2024, Babcock University conferred on him the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Law and Administration. By the grace of God, on Monday, 20th of October, 2025, Chief Olanipekun will be conferred with yet another Honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D, honoris causa) by the arguably the best private university in Nigeria, the Afe Babalola University, Ado Ekiti (ABUAD).

By conferring on Chief Olanipekun the Platinum Alumni Award, the Alumni Association of the University of Lagos honours not just a legal luminary, but a national treasure whose life’s work continues to inspire, influence, and illuminate paths for future generations. This

Celebrating a Living Legend

The UNILAG community, alumni around the world, and countless beneficiaries of Chief Olanipekun’s mentorship and magnanimity join in celebrating this well-deserved recognition. It is a moment of pride, a symbol of gratitude, and a reaffirmation that true greatness is not only measured by personal accomplishments but by the lives touched and institutions strengthened along the way.

As he receives the Platinum Alumni Award, Chief Wole Olanipekun, SAN, CFR, stands tall, a living testament to what it means to learn, serve, lead, and leave a legacy of excellence.

Congratulations my leader and father, Chief Wole Olanipekun, CFR, OFR. SAN — May your light forever shines brighter.

Adesina Adegbite, FICMC, MCIArb (Bencher)

Secretary, West African Bar Association (WABA), and the Immediate Past General Secretary, Nigerian Bar Association (NBA)

Lagos, Nigeria — 17th, October 2025

by Legalnaija | Oct 16, 2025 | Blawg

Chief Wole Olanipekun To Bag ABUAD Honorary Doctoral, UNILAG Alumni Platinum Award

Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) and former chairman ,Body of Benchers ,Chief Wole Olanipekun ,SAN ,CFR will be receiving double awards from two prestigious universities in Nigeria .

The Nigeria’s foremost Legal Practitioner will be conferred with the Honorary Doctor of Laws, LL. D honoris causa by the fastest growing private university in Africa , Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti(ABUAD) at its forthcoming 13th Convocation ceremonies.

Chief Olanipekun,the Asiwaju of Ikere-Kingdom ,will also deliver the ABUAD’s Convocation Lecture titled: “Nigeria Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, The Imperative of a Sober and Definitive Recalibration” on Monday, at the Alfa Belgore main auditorium .

Similarly , arrangements are in top gear by the leadership of the University of Lagos Alumni Association to bestow the highest honour of the UNILAG ALUMNI PLATINUM Award on Chief Olanipekun .

The UNILAG Alumni event is scheduled to hold on Friday, October 17, 2025 at the Eko Hotels & Suites, Victoria Island ,Lagos under the chairmanship of the Ogbeni Oja of Ijebu land ,Olor’ ogun , Dr Sonny Kuku ,OFR, FAS ,while the Vice President ,Senator Kassim Shettima will be the Special Guest of Honour .

Engineer Ifeoluwa Ayodele,FNSE ,FA Eng, the President Worldwide of the UNILAG Alumni is the Chief Host .

Chief Olanipekun is the Pro Chancellor and chairman of council , University of Lagos .He built a strong reputation across many areas of law (constitutional, arbitration, commercial, etc.).

In 1980, he founded Wole Olanipekun & Co., which has grown into one of Nigeria’s leading law firms with a presence across states .

In 1991, he was appointed Attorney General and Commissioner for Justice of Ondo State, serving for approximately two years

He served as President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) from 2002 to 2004 . In 2007, he was made a Life Bencher (by the Nigerian Body of Benchers)

He has also held roles as Pro-Chancellor / Chairman of Governing Councils at various universities: - University of Ibadan (2004 – 2006) - Ajayi Crowther University, Oyo State .

Chief Wole Olanipekun has been involved in high-profile cases and election petitions, contributing to Nigeria’s jurisprudence and constitutional law development.

by Legalnaija | Oct 15, 2025 | Blawg

THE FACT OF THE CASE BRIEFLY GOES AS FOLLOWS:

The appellant publicly claimed to have discovered a vaccine for HIV and to have cured patients. His claim drew reactions from the 1st and 2nd respondents, who are the Minister of Health and the Medical & Dental Council of Nigeria respectively. Thereafter, the 3rd respondent (Medical & Dental Practitioners Investigating Panel) invited him over alleged professional misconduct. Rather than honouring the invitation, he went to the High Court of the FCT, claiming that the panel was acting as accuser, prosecutor, and judge in its own case, thereby violating his right to fair hearing. The court first granted an interim order but later struck out the motion on jurisdictional grounds.

He furthermore approached the Federal High Court again to enforce his fundamental right being likely to be breached by the panels, arguing that the panels were biased and under the control of the Minister of Health. The court dismissed his case, holding that his complaints and the reliefs he sought were outside the provisions of Chapter IV of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), and were not enforceable under the Fundamental Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules. Dissatisfied, he appealed to the Court of Appeal but failed, and then further appealed to the Supreme Court.

DECISION vis-à-vis ANALYSIS OF THE CASE:

The Supreme Court, per ABBA AJI, J.S.C. (delivering the leading judgment), set aside both the judgments of the trial and lower courts for want of jurisdiction, emphasizing the importance of jurisdiction. The Court held that though the issue and the claims therein are fundamental-right related, as the appellant alleged that his right to fair hearing pursuant to section 36(1) was likely to be breached by the panels, HOWEVER an action against a non-judicial body for enforcement of right to fair hearing cannot be filed under the Fundamental Rights Enforcement Procedure, because section 36(1) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended) provides that: ‘In the determination of a person’s civil rights and obligations, including any question or determination by or against any government or authority, the person shall be entitled to a fair hearing within a reasonable time by a COURT or other TRIBUNAL established by law and constituted in such a manner as to secure its independence and impartiality.’

It’s from the foregoing that the supreme court submitted that the section only dealt with the determination of the civil rights and obligations of a person in cases before a COURT or a TRIBUNAL established as such by law. In other words, the section applies only to proceedings before JUDICIAL BODIES established as such by law and does not extend to all BODIES ACTING JUDICIALLY OR QUASI-JUDICIALLY including domestic or standing ad-hoc tribunals or panels raised departmentally or in an organization to investigate, inquire into, or hear complaints within that department or organization.

In the instance case, the suit by the appellant that the proceedings and decisions of the respondents VIOLATE or are LIKELY TO VIOLATE the PRINCIPLES OF NATURAL JUSTICE against him and his general legal right to fair hearing is a proper and recognizable complaint in law, HOWEVER, the RESPONDENTS NOT BEING COURTS OR TRIBUNALS ESTABLISHED BY LAW, their alleged violation or likely violation of the principles of natural justice against him and his general legal right to fair hearing cannot be brought before the High Court by way of an application for enforcement of fundamental rights pursuant to section 46(1) of the 1999 Constitution and the Fundamental Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules. But the appellant can seek redress for such violation by the ordinary or general processes for seeking remedy for infractions of legal rights and obligations in the High Court.

My Lords further emphasized that the appropriate thing he ought to have done, or the appropriate method to challenge decisions of non-judicial bodies acting judicially or quasi-judicially, is by an application for judicial review by way of a writ of certiorari, prohibition, declaration, or by any of the ordinary methods of legal actions such as writ of summons, originating summons, or originating motion under the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules.

In addition, the Supreme Court further addressed the question of what happens where the issue complaint involves a fundamental right and other multiple issues? It was wittingly and precisely held that: where a set of facts or cause of action gives rise to multiple causes of action, including a breach of fundamental rights, the party so affected would have to bring two different actions at the same time. The appropriate procedures must be adopted for each class of action. One of such actions is by writ of summons according to the provisions of the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules of the relevant State, and the other by the most suitable originating process, as the case requires, under the Fundamental Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules.

Lastly, Supreme Court summed it up with the proper order to be given where the main claim in an action for enforcement of fundamental rights does not fall under Chapter IV of the 1999 Constitution that the proper order the court should make is an order striking out the action on the ground that the court lacks jurisdiction to entertain it. Therefore In the instance case, the trial court and, latter, the Court of Appeal ought to have struck out the appellant’s action after noticing the matter doesn’t fall within the scope of Chapter IV warranting it to be brought under fundamental enforcement procedural rules, and that embarking on making findings was an exercise in futility as it has been a settled and aged long position of law re-echoed in plethora of cases that: All law courts or tribunals, while exercising their powers, must be guided by the general determinants of jurisdiction among which are:

(a) the statute establishing the court/tribunal;

(b) the subject matter of litigation;

(c) the litigating parties;

(d) the procedure by which the case is initiated;

(e) proper service of process;

(f) the territory where the cause of action arose or where the defendant resides; and

(g) the composition of the court/tribunal.

Therefore if any of the above is lacking, the jurisdiction of such Court/tribunal is defective and would undoubtedly lead the whole trial to a nullity.

Briefly put:

Where it’s not a Court of Law or a tribunal established by law that breaches or is likely to breach someone’s fundamental rights such as fair hearing, but rather it’s an administrative or organizational body/panel or commission of inquiry, in other words, it’s a non-judicial body acting judicially or quasi-judicially, the best way to challenge that, is by an application for judicial review by writ of certiorari, prohibition, declaration, or by any of the ordinary methods of legal actions such as writ of summon etc. But where the breach is by a Court of Law or tribunal established by law, then it falls within the scope of Chapter IV and can be filed or brought under the Fundamental Rights Enforcement Procedure Rules. Equally, the appropriate order ought to be given right at the trial court, having found that the claim doesn’t fall within the scope and was brought under fundamental rights enforcement procedure rule instead of bringing it by way of judicial review is to strike it out for lack of jurisdiction and doing anything further was an exercise in futility. As such both the trial court and the Court of Appeal decisions are of no effect whatsoever therefore are liable to be set aside.

N:B: In essence, if the classical case of Garba v. Unimaid were to come up today, it might have faced a procedural challenge for being filed under fundamental rights enforcement rather than judicial review.

Funny enough, I did a moot in the just concluded semester on a fact almost similar to Garba v. Unimaid. But I refused to follow the mode adopted by the learned counsel in that case: filing a suit for enforcement of fundamental rights. I went by way of judicial review. I could remember I consulted two of my seniors Abubakar Abdullahi Raji, Senior Advocate of Bayero University Kano (SABUK), and Salihu Haruna, SABUK about it, and they said I should give it a try, so I filed an ex parte motion for leave alongside my main application for judicial review. As if I knew this Supreme Court pronouncement was coming to validate it.

__________________________________________

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

isahbalagarba05@gmail.com or on 08100129131

OKOROTE OZIOMA NWACHUKWU is a passionate litigation lawyer with a growing interest in taxation, tax reform and governance. Her interest in tax law is driven by a conviction that Nigeria can overcome its mounting debt not only through financial discipline but by giving earnest attention to taxation as a sustainable means of generating revenue and funding national development.

OKOROTE OZIOMA NWACHUKWU is a passionate litigation lawyer with a growing interest in taxation, tax reform and governance. Her interest in tax law is driven by a conviction that Nigeria can overcome its mounting debt not only through financial discipline but by giving earnest attention to taxation as a sustainable means of generating revenue and funding national development.

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba