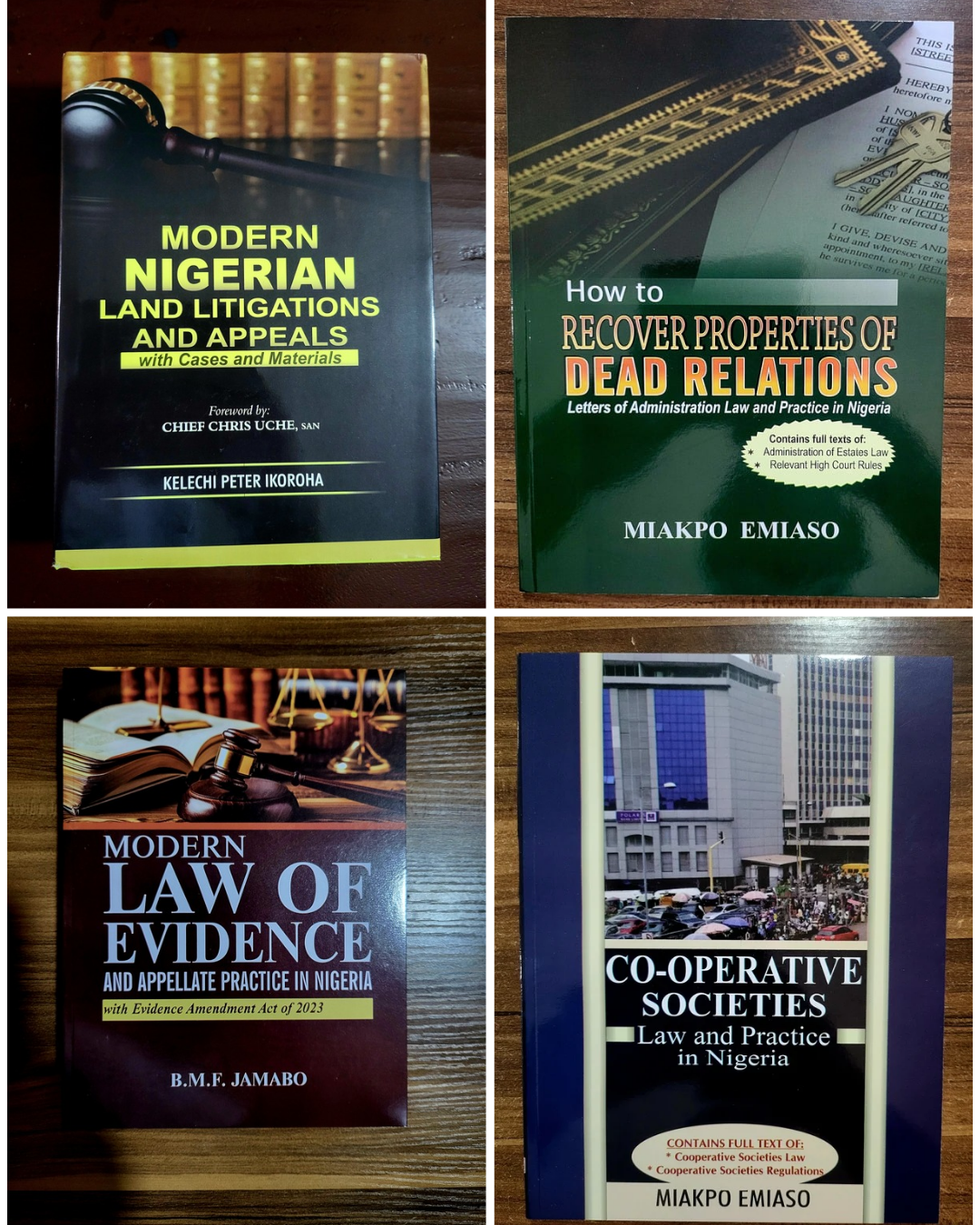

LAW TEXTBOOKS FLASH SALE – 35% OFF LEGAL TITLES

- Use coupon code **WIGANDGOWN** at checkout

- Offer valid for 36 hours only!

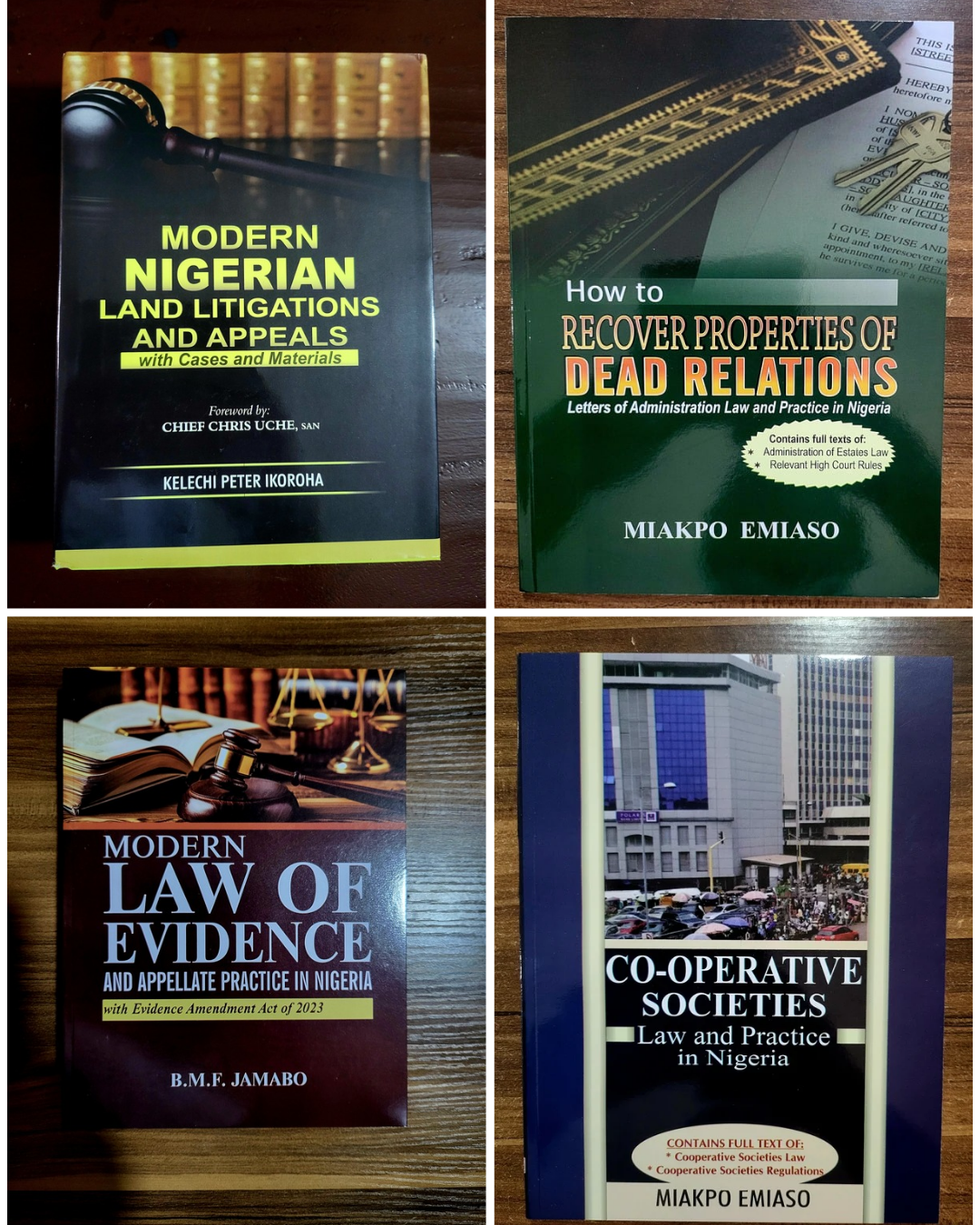

NBA Legal Education Committee calls for climate-competent lawyering in line with global best practicesop

The Legal Education Committee of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA-LEC) has called on lawyers to fully integrate corporate due diligence on environment, social, governance (ESG) and human rights, when providing counsel. They also called on governments at all levels to provide increased funding for legal education in Nigeria in order to enhance the development of climate-competent lawyers that can effectively advise clients on global best practices relating to climate change, biodiversity, pollution control and sustainable development in infrastructure and development projects.

These recommendations were made at the 3rd online Seminar Series on Legal Education organized by the NBA-LEC. Recall that as part of the NBA’s efforts to enhance legal education and practice in Nigeria, NBA President, Mazi Afam Osigwe, SAN inaugurated the Legal Education Committee under the leadership of Professor Damilola Sunday Olawuyi, SAN, Deputy Vice Chancellor at Afe Babalola University, Ado Ekiti (ABUAD), with the mandate to promote and advance functional legal education in Nigeria, especially through training sessions and conferences on modern teaching approaches.

In exercise of this mandate, the NBA-LEC introduced the Webinar Series on Legal Education Series, a gathering of academic, legal practitioners and industry experts to discuss practical approaches for promoting the reform and transformation of legal education in Nigeria. This 3rd edition of the series recorded a huge turn out of more than 850 attendees.

While welcoming delegates to the workshop, Chairman of the NBA-LEC, Professor Damilola Olawuyi, SAN highlighted that the rapid introduction of ESG standards in legislation, industry guidelines, and contracts worldwide to address planetary emergencies, such as climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution in key sectors, is transforming the legal profession, especially the meaning of contractual due diligence and the way we practice and teach law. According to the Learned Silk, “to be a competent lawyer in this rapidly changing regulatory landscape includes being commercially aware of climate and energy transition risks. It is for this purpose in that we have put together this Webinar Series to provide an opportunity for stakeholders in legal education, particularly faculty, students, and administrators to explore how to tailor legal education to meet contemporary realities and needs.”

On his part, the keynote speaker, Prof. Onyeka K. Osuji, Dean and Professor of Law, Essex Law School, University of Essex, United Kingdom highlighted the nature, scope and application of ESG in transactional and regulatory context. He noted that the emerging ESG standards place additional duty of care on lawyers to acquire the knowledge, skills, attitudes, dispositions and competencies required to provide risk-free legal advice in today’s rapidly changing world. Drawing from his extensive experience in the UK, the erudite professor also stressed that to effectively perform these roles, legal educators must integrate practical skills in legal education and training both at the University and bar training.

Moderated by the chairperson of the Webinar Series subcommittee of NBA-LEC, Ozioma Soludo, who is also an associate at KENNA, the ensuing panel discussion featured insightful contributions from leading practitioners from Nigeria and beyond. The panelists, Mrs Folashade Alli, SAN, one of the leading arbitrators in Nigeria with about 40 years’ practice experience and current Chairperson of the Section on Legal Practice of the Nigerian Bar Association; Professor Ayodele Morocco-Clarke, Professor of Energy, Climate and Environmental Law and Policy at Nile University of Nigeria, Abuja, as well as Paula-Ann Novotny who is a partner at the global law firm, Webber Wentzel and member of the Business and Human Rights Committee of the International Bar Association, expertly analysed the meaning of ‘climate-competent lawyering’ in Nigerian and global contexts. The discussions also examined the ESG imperatives and the challenges and opportunities for legal education and professional training; the urgent need for universities to integrate climate change and ESG into law curricula and professional standards, as well as comparative perspectives and lessons from global best practices in climate-related legal education. The speakers also highlighted the future role of lawyers in advancing sustainability and regulatory compliance in line with global best practices.

While discussing the way forward, the workshop commended the NBA leadership for providing the innovative platform to reflect on the way forward and called for the swift implementation of the NBA Legal Education Endowment Fund which could go a long way in mobilizing financial support for infrastructure and technology upgrade to implement practice-focused training in universities. While calling on law firms, companies and other stakeholders to contribute to the Fund, the workshop also called for more joint research projects between NBA and law faculties, as well as tailored research programs and subsidized conferences for academic lawyers, as a way of incorporating theoretical and practical law aspects in the profession.

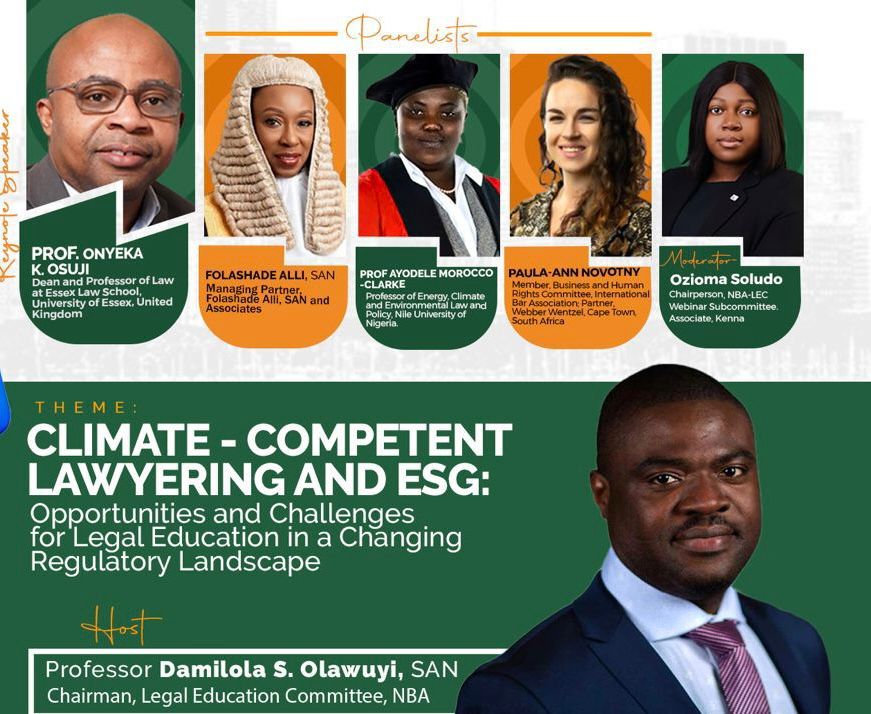

Early bird registration for the ICSAN Lagos State Annual Summit has been extended to 5th October, 2025*

Join the greatest minds in corporate governance at the ICSAN Lagos State Chapter Annual Summit 2025, an unmissable event designed to empower professionals navigating today’s evolving business landscape.

🔍 Theme:

“Governance Redefined in a Business Environment: A Continuum or New Paradigms?”

🗓 Date: Thursday, 30th October 2025

🕙 Time: 10:00 AM

📍 Venue: The Jewel Aeida, Plot 105, Hakeem Dickson Link Road, Lekki Phase 1, Lagos

🎯 Why Attend?

✅ Gain fresh insights into emerging governance trends

✅ Network with top professionals and industry leaders

✅ Explore real-world strategies for effective governance

✅ Earn professional recognition and visibility

Registration Rates:

🔹 Members: Early Bird – ₦40,000 | Regular – ₦50,000

🔹 Non-Members: Early Bird – ₦55,000 | Regular – ₦65,000

*ONLINE PAYMENT LINK:*

Click on the link below to make payment for the Annual Summit

http://bit.ly/3JLzrhG

📞 For inquiries: 08034689366

After payment, please click on the link to register

https://forms.gle/Z1JwEukP8H51oLVw5

📲 Follow: @icsanlagosstatechapter

Attendance attracts points for Membership upgrade

Don’t miss it!

#ICSANAnnualSummit2025

#ICSANLagosCGWeek2025 #governanceredefined

The JAALS Foundation, in its effort to facilitate the reform of the justice system, last year, organized the Walk for Justice, an exercise that saw lawyers, members of the Nigerian Bar Association and the civil public march from Falomo bridge to the Federal High Court, Lagos. In the course of engagement with judicial officers in the court, the need to prioritize capacity building for bailiffs was indicated. To that effect, the foundation organized an intensive training for bailiffs of the Federal High Court, Lagos, amplifying their technical capacity and elevating the quality of their work in expediting justice processes.

Meanwhile, the Nigerian Justice system has, over the years, been infamously riddled by corruption. In 2024, Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index ranked Nigeria 140th of 180 countries, with a score of 26 over 100. Thus, at this year’s Walk for Justice in February, JAALS led almost 100 participants in a walk to the ICPC office in Ikoyi to engage with the anti graft agency on tackling the menace of corruption and improving the overall quality of justice administration in Nigeria. Albeit, The 2024 WJP Rule of Law Index’s assessment of Nigeria’s justice system reveals a deeper truth: the quagmire besetting the effective delivery of justice in Nigeria is not limited to corruption within the system, but also the absence of genuine institutional collaboration. Nigeria’s justice system was ranked 120th out of 140 countries, with concerningly low scores across civil justice (0.34), criminal justice (0.36) and government oversight (0.35). This conclusion was reinforced upon consultation with the ICPC, who emphasized the lack of institutional collaboration between anti graft agencies, law enforcement and other stakeholders in the Justice sector.

To confront this challenge head-on, the JAALS Foundation is convening the 2025 Virtual Justice Reform Roundtable on October 1st, 2025, themed:

“Strengthening Institutional Synergy: A Catalyst for Effective Justice Delivery?”

This dialogue will bring together stakeholders from law enforcement, the EFCC, ICPC, Code of Conduct Bureau, Nigerian Correctional Service, the judiciary, and the bar. In this consortium, institutional isolationism will be addressed, and concrete pathways for collaboration explored.

We are calling on lawyers, justice advocates, civil society actors, and members of the public to join us in this critical conversation. Together, we can lay the foundation for a justice system that commands public trust and serves the nation faithfully.

📅 Date: Wednesday, October 1, 2025

⏰ Time: 2:00 p.m.

📍 Venue: Virtual (link provided upon registration)

To register, scan the QR code on the flyer or click the link: https://bit.ly/47waIHR

SAVE THE DATE

“In furthering my longstanding passion and commitment to continuing professional development, I have, with the kind support of some friends and colleagues, now launched *The Practical Training Academy (TPTA)*, as an institution dedicated to deepening and democratising knowledge in the legal profession by providing high-quality trainings and courses to Nigerian lawyers free of charge, with the required CPD points awarded for every training session. – TOBENNA EROJIKWE

*THE LAUNCH OF THE PRACTICAL TRAINING ACADEMY AS A PLATFORM FOR FREE AND HIGH QUALITY CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVES FOR NIGERIAN LAWYERS*

Over the course of my two decades of legal practice across various jurisdictions, I have had the privilege of coordinating and leading continuing professional development initiatives for my colleagues. My journey began as a Learning and Development Lead early in my career, and I have since had the honour of serving as a Law Society of England and Wales accredited facilitator. My commitment to professional development continued as I became the Chairman of the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Committee of the NBA Lagos Branch for four years, and later, the Chairman of the Board of the NBA Institute of Continuing Legal Education (NBA-ICLE) for nearly another four years.

During my tenure as Chairman of the CPD Committee of the Lagos Branch, I was fortunate to lead an extraordinary team, that achieved significant milestones such as hosting over 48 Knowledge Sharing Sessions and establishing a 220-person mentorship program, among other training and development initiatives. Similarly, while leading the NBA-ICLE, I worked with incredibly talented and dedicated colleagues to transform the institute from a cost center into a self-sustaining institution capable of financing its operations and functioning independently. We played a pivotal role in capacity building, mentorship, and expanding lawyers’ practice areas by facilitating over 200 training sessions across 40 areas of law and 127 thematic topics, with an unmatched record of over 60,000 participants attending our sessions for free.

Our efforts in the training and development space stemmed from recognising a significant knowledge gap within the legal profession in Nigeria, which hindered the delivery of quality services across various segments of the economy. Despite our progress, these knowledge gaps persist, and the desire for growth and development among legal professionals remains strong.

Driven by my passion and commitment to continuing professional development, I believe it is crucial to have a platform focused on democratising learning, deepening knowledge, and enabling lawyers to expand their practices by exploring new areas. This belief has now led me, with the kind support of some friends and colleagues, to establish *The Practical Training Academy (TPTA)*, an institution dedicated to providing high-quality training and courses to Nigerian legal professionals free of charge.

I am pleased to announce that TPTA has recently been accredited as an NBA-ICLE Service Provider, making the platform eligible to offer professional development trainings and award the credit points required of lawyers. We have meticulously prepared a comprehensive and data-driven syllabus covering various subjects and practice areas. We have also engaged and are in discussions with esteemed and prominent lawyers, including in-house counsel, private practitioners, law officers, and foreign law firms who will be part of our faculty to deliver these trainings on a continuous basis.

I would like to extend our gratitude to the institutions and organisations that have agreed to collaborate and partner with us in pursuing this noble and altruistic objective. I am confident that through these trainings, TPTA will add significant value to the practices of all our colleagues who participate while earning CPD points at no cost. Our course outline and training schedule will be released in the coming weeks.

I thank you for your attention.

*TOBENNA EROJIKWE*

Senior Partner, The Law Crest

14th September, 2025

NBA Lagos Branch Embarks on a Protest Against the Nigerian Navy’s Disregard of Court Judgment

The Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), Lagos Branch, on Friday, 12th September 2025, staged a peaceful protest against the Nigerian Navy’s unlawful signal, declaring its member, Vice Admiral Dada Olaniyi Labinjo (Rtd.), as a “deserter,” in defiance of a valid judgment of the National Industrial Court.

Led by the Branch Chairman, Mrs. Uchenna Ogunedo Akingbade, members of the Executive Committee and several lawyers converged at Marine Bridge, Apapa, where they were met with a heavy security presence of armed Police, Military personnel, DSS operatives, and Lagos State Neighbourhood Safety Corps officers.

Despite initial hostility, the lawyers stood their ground and by 11:00 a.m., marched to NNS Beecroft, Apapa, where they were received by Naval officers and later addressed by Commodore Paul Ponfa Nimmyel.

Mrs. Akingbade presented the purpose of the protest:

To condemn the Navy’s disregard of a subsisting Court judgment.

To deliver a protest letter to the Chief of Naval Staff through the Flag Officer Commanding.

However, Commodore Nimmyel refused to accept the letter on behalf of the Navy, insisting it should be delivered directly to the Chief of Naval Staff in Abuja, while suggesting dialogue before protest. In response, Mrs. Akingbade firmly countered that:

He who comes to equity must come with clean hands. You cannot call for dialogue while disobeying a Court order and persisting in unlawful actions against our member.

Present at the protest were Branch officers, including Mr. James Sonde (Vice Chairman and Chairman, Human Rights Committee), Mr. Kelechukwu Uzoka (Secretary), Mrs. Oge Mokelu (Treasurer), Mr. Oliver Omoredia (Publicity Secretary), branch members such as Mrs. Oyinkansola Badejo-Okusanya, Mrs. Chinelo Okonkwo, Mr. Shola Lamid, Mr. Victory Ilugo and prominent branch members turned out for the protest.

The NBA Lagos Branch reaffirmed its commitment to defending the Rule of Law, stressing that disobedience of Court orders by institutions poses a grave danger to Nigeria’s democracy.

Colonial Shackles on Justice Delivery: A Constitutional Critique Of Section 84 Sherrif & Civil Process Act Through The Lens of Central Bank of Nigeria v. Inalegwu Frankline Ochife & 3 Ors (2025) LPELR-80220 (SC) by Nonso Obiadazie Esq.

Introduction

Enforcement of court judgment is an important part of our adversarial system of adjudication. Upon the final determination of a case resulting in a monetary judgment, it is the duty of the successful party (“judgment creditor”) to initiate enforcement proceedings to compel compliance of the judgment. One of the ways to achieve this is through garnishee proceedings. This type of judgment enforcement mechanism allows the judgment creditor to seize funds held by third parties (usually financial institutions) on behalf of the unsuccessful party (“judgment debtor”). This is necessary because the adversarial nature of our legal system does not ensure the automatic satisfaction of a judgment debt. Enforcing a monetary judgment against a private person usually presents little difficulty. The judgment creditor can easily proceed against third parties who hold funds on behalf of that private person and can recover the judgment sum without needing his consent.[1] However, the case is different where the judgment debtor is the Government or any of its agencies, as Section 84 of the Sheriffs and Civil Process Act (“SCPA”) imposes a statutory requirement for obtaining prior consent from the Attorney General of the Federation or of a State before enforcement proceedings can be initiated by the judgment creditor. This requirement traces back to a colonial-era doctrine which held that the “Crown could do no wrong”.

Under this doctrine, it was necessary to seek and obtain the Crown’s consent before suing or enforcing a judgment against it. Despite Nigeria’s independence from colonial rule and the constitutional mandate requiring that court decisions be enforced against all authorities and individuals without the need for prior consent,[2] this colonial doctrine, preserved through statutory provisions, continues to hold sway in our legal system. Thus, this article will examine the constitutionality of Section 84 of SCPA, with a critical analysis of the recent Supreme Court’s decision in Central Bank of Nigeria v. Inalegwu Frankline Ochife & 3 Ors, paying particular attention to the dissenting opinion delivered by His Lordship, Hon. Justice Helen Ogunwimiju, JSC. The case has become a focal point for reassessing whether such colonial doctrine can coexist with Nigeria’s constitutional order founded on justice, democracy and separation of powers.

2.0 Colonial History of Section 84 of the Sheriffs and Civil Process Act

The provision was first introduced in Nigeria as the Sheriffs and Civil Process Ordinance of 1st June 1945. In the lead-up to Nigeria’s independence, it was incorporated into the Laws of the Federation of Nigeria and Lagos, 1958.[3] Following independence in 1960, the Ordinance was preserved as an existing law pursuant to the 1960,[4] 1963,[5] 1979,[6] and 1999[7] Constitutions of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. It provides as follows:

“84. (1) Where money liable to be attached by garnishee proceedings is in the custody or under the control of a public officer in his official capacity or in custodia legis, the order nisi shall not be made under the provisions of the last preceding section unless consent to such attachment is first obtained from the appropriate officer in the case of money in the custody or control of a public officer or of the court in the case of money in custodia legis, as the case may be.

(2) In such cases the order of notice must be served on such public officer or on the registrar of the court, as the case may be.

(3) In this section, “appropriate officer” means-

(a) in relation to money which is in the custody of a public officer who holds a public office in the public service of the Federation, the Attorney-General of the Federation;

(b) in relation to money which is in the custody of a public officer who holds a public office in the public service of the State, the Attorney-General of the State.”

Where money liable to be attached by garnishee proceedings is in the custody or under the control of a public officer in his official capacity or in custodia legis, the order nisi shall not be made under the provisions of the last preceding section unless consent to such attachment is first obtained from the appropriate officer in the case of money in the custody or control of a public officer or of the court in the case of money in custodia legis, as the case may be.

The provision is to the effect that where a person obtains a monetary judgment, and the funds to be attached or seized are in the custody of a public officer, the person as a judgment creditor is prohibited from attaching such funds, unless prior consent is obtained from the Attorney General of the Federation or of a State, as the “appropriate officer”. In this context, where the government or any of its agencies is a judgment debtor in a monetary judgment, the judgment creditor cannot initiate enforcement proceedings against the Central Bank of Nigeria without first obtaining prior consent. Such consent must be sought and obtained before the court can entertain any enforcement proceedings brought by the judgment creditor.

Order at www.legalnaija.com/bookstore

It is our view that Section 84 of SCPA is a relic of colonial legal doctrine, rooted in the principle of “rex non potest peccare” which means that the Crown—or the State—could do no wrong. This English doctrine is also known as “sovereign immunity” and it means that the Crown/State could not be sued for any wrongdoing, nor could a judgment be enforced against it. Yousufi argues that the reason for the immunity of crown is not because of the feeling that the crown is above the law, but because there was no court above the court of the crown.[8] As a result of this legal barrier, people needed a legal workaround to enable individuals to seek redress against the Crown in court. This led to the enactment of the Petition of Rights Act in 1860 and Section 4 of SCPA in 1945 by the English authorities. Both legislations provided a statutory framework through which individuals could submit a petition of rights to the Crown, seeking its consent to sue or enforce a judgment against it. Nigeria by colonial affiliations inherited these legal traditions from the British and it became part of our laws upon independence in 1960.[9] The applicability of these statutes in Nigeria was judicially affirmed in the landmark case of Ransome-Kuti & Ors v. Attorney-General of the Federation.[10] In this case, the home of a famous Afrobeat musician, Fela Kuti, was invaded in 1977 by soldiers following an earlier clash with his staffs. The soldiers, numbering over One thousand (1000), forcibly entered Fela’s home by dismantling the wire fencing. They proceeded to eject all occupants from the house, with the exception of Fela’s mother and brother. Subsequently, the soldiers moved to the main residential building, which they deliberately set on fire. They instituted an action against the Federal Government, seeking to hold it vicariously liable for the wrongful acts of its soldiers. The Federal Government relied on the defence of rex non potest peccare, contending that it was immune from suit and that the claim was incompetent, as the Claimants had failed to obtain the requisite consent of the Attorney-General of the Federation under the Petition of Rights Act before commencing the action. The trial court, on that basis, dismissed the suit. The Claimants appealed to the Court of Appeal, which also dismissed the appeal. Dissatisfied, they further appealed to the Supreme Court, which, in upholding the principle of Crown immunity, held as follows, per Karibi-Whyte, JSC:

“The infallibility of the State which clothes it with immunity for wrongs committed on is behalf is still with us. Since the theory that public revenue cannot be made liable to remedy wrongs committed by servants of the State without its consent is the governing consideration, it requires a revolutionary amendment of the law to render the State liable for wrongs committed by its representative servants. Until this is done the common law remains applicable.”[11]

The Supreme Court did not hesitate to dismiss the appeal, citing state immunity and the appellants’ failure to obtain the state’s consent as required by Petition of Rights Act. However, the Court also suggested a revolutionary legal amendment to make the state liable for its wrongs. This suggestion was later adopted in the 1979 Constitution, which removed the requirement to obtain state consent before suing the government. This was judicially affirmed in the case of Government of Imo State v. Greeco Construction & Engineering Ltd.[12] The Respondent sued the Appellants for the balance of N20, 979.80 (Twenty Thousand, Nine Hundred and Seventy-Nine Naira, Eighty Kobo), due in respect of a contract agreement entered into by both parties for the building of residential quarter for lawmakers. The contract was duly performed but the Appellants refused to pay the balance claimed . The Appellants, as in the Ransome-Kuti case, argued that the State Government was immune from a law suit and that the Respondent had failed to obtain the Imo State Government’s consent, as required under Sections 4 and 5 of the Petition of Rights Law, before initiating the action. The trial court entered judgment in favor of the Respondent. Dissatisfied with the decision, the Appellants appealed to the Court of Appeal. Upon review, the Court of Appeal held that the provision of the Petition of Rights Law requiring prior consent to initiate lawsuits against the government was unconstitutional, as stated in the following terms, per Olatawura, J.C.A:

“The right to refuse the fiat under section 5 of the petitions of Right Law is final and conclusive. There is no provisions for redress once the fiat is refused. In other words, a citizen who conies by way of the Petitions of Right Law and is refused the fiat of the Governor is without remedy. The refusal is “final and conclusive.” Consequently, he is denied access to the court. This will be contrary to section 6(6)(b) of the 1979 Constitution which provides:

“6. The judicial powers vested in accordance with the foregoing provisions of this section.

(b) shall extend to all matters between persons, or between government or authority and any person in Nigeria, and to all actions and proceedings relating thereto, for the determination of any question as to the civil rights and obligations of that person.”[13]

It is important to note that although the requirement to obtain the State’s consent before initiating legal action has been abrogated by both constitutional provisions and judicial pronouncements, however, the second limb of the Crown immunity doctrine—requiring consent before enforcing a court judgment against the State under Section 84 of SCPA—remains intact. This aspect has not yet been judicially invalidated, despite constitutional provisions that arguably support its abolition.

3.0 Ogunwumiju JSC’s Judicial Activism in CBN v. Frankline Ochife & Ors: Upholding Unrestricted Judgment Enforcement Under the 1999 Constitution

The concept of judicial activism is not new to our jurisprudence and has no straight-jacket definition. Its usage depends on the user’s context particularly in relation to the role of the judiciary within a constitutional democracy. However, according to Peter Russell, “judicial activism is the judicial readiness in enforcing constitutional limitations on the other branches of government.”[14] His Lordship, Ogunwumiju JSC, exemplified this stance in Frankline Ochife’s case, where His Lordship took a bold step in enforcing an unrestricted judgment enforcement under the 1999 Constitution, thereby affirming the constitutional limits of executive authority over judicial decisions. As previously stated, the requirement to obtain the Attorney General’s consent before enforcing a judgment against the State is part of the broader colonial Crown immunity doctrine, which requires consent both in initiating legal action and enforcing judgments against the State. While the requirement to obtain consent to sue the State has been invalidated through constitutional[15] and judicial[16] pronouncements, the requirement to obtain consent before enforcing a judgment, particularly monetary judgments, remains operative, despite constitutional provisions to the contrary. In our view, this requirement is inconsistent with the Constitution, specifically Section 287, which guarantees unrestricted enforcement of judicial decisions. Section 287 provides as follows:

“(1) The decisions of the Supreme court shall be enforced in any part of the Federation by all authorities and persons, and by courts with subordinate jurisdiction to that of the Supreme Court.

(2) The decisions of the Court of Appeal shall be enforced in any part of the Federation by all authorities and persons, and by courts with subordinate jurisdiction to that of the Court of Appeal.

(3) The decisions of the Federal High Court, National Industrial Court, a High Court and of all other courts established by this Constitution shall be enforced in any part of the Federation by all authorities and persons, and by other courts of law with subordinate jurisdiction to that of the Federal High Court, National Industrial Court, a High Court and those other courts, respectively.”

The provision imposes a binding obligation on all persons and authorities to comply with decisions of courts. This obligation is absolute, subject only to the right of appeal. It also embodies two critical principles: first, it affirms the supremacy of judicial decisions; and second, it eliminates any discretionary power in the enforcement of such decisions, ensuring that compliance is mandatory and non-negotiable. It is submitted that the supremacy of judicial decisions is absolute, particularly within Nigeria’s federal system of government, where the Constitution stands as the supreme law of the land. Consequently, any law that conflicts with the provisions of the Constitution, such as Section 84 of SCPA, must defer to it.[17] However, despite this explicit constitutional mandate, Nigerian courts (Court of Appeal) still continue to apply Section 84 of SCPA.[18] The continued application has led to grave injustice, as parties who have endured the stressful process of litigating against the government are still compelled to seek its consent before enforcing a judgment—thus allowing the State to act as both adversary and gatekeeper to justice. This is unacceptable.

In January 2025, the Supreme Court was presented with a sweet opportunity to interpret Section 84 of SCPA in light of Section 287 of the 1999 Constitution in Frankline Ochife’s case (supra). However, the Court ignored its interpretative role and relied instead on procedural technicalities in dismissing the appeal. But, Ogunwumiju, JSC, in a powerful and well-reasoned dissent which we endorse effectively dismantled the last colonial remnants of the crown immunity doctrine and reaffirmed the supremacy of our Constitution. The facts of the case is simple. The 1st Respondent obtained a judgment in the sum of ₦50 million against the Inspector General of Police (IGP), the Commissioner of Police, FCT (COP), and the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) of the Nigeria Police Force. Following the judgment, the 1st Respondent initiated garnishee proceedings to recover the judgment sum. Upon being served with the Order Nisi, the Appellant filed an affidavit to show cause, asserting that the IGP, COP, and SARS did not maintain any account with the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). The trial court, however, disregarded the affidavit and proceeded to make the Order Nisi absolute against the Appellant. Dissatisfied with the decision, the Appellant appealed to the Court of Appeal, which dismissed the appeal. On further appeal to the Supreme Court, the Appellant raised the issue that the 1st Respondent had failed to seek and obtain the consent of the Attorney General of the Federation under section 84 SCPA before initiating the garnishee proceedings, thereby rendering the trial court without jurisdiction to entertain the suit. The Supreme Court, in a 4-1 decision, held that the issue of consent was not raised at the trial court and, as such, could not be raised for the first time on appeal. The Court further held that the failure to obtain consent constituted a procedural irregularity, which the Appellant had waived by not raising it earlier at the trial court. The majority decision of the Supreme Court made no attempt to interrogate the constitutionality of Section 84 of SCPA. In contrast, the dissenting opinion of Ogunwumiju, JSC stood as a lone voice of judicial activism. His Lordship used two key points in dismantling Section 84 SCPA. The first was a historical analysis. His Lordship observed that Section 287 of the 1999 Constitution was a product of Section 251 of the 1979 Constitution, both of which affirmed the binding and unrestrictive nature of judicial decisions. To constitutionalize Section 84 of the SCPA, the Military Government promulgated Decree No. 107, by inserting Section 84 under Section 251(4) of the 1979 Constitution. It provides as follows:

“(4). Notwithstanding the provisions of this section, no person shall enforce a judgment against a ministry or extra-ministerial department without the fiat of the Attorney General of the Federation or the Attorney General of a State, whether or not he was, in either case, a party to the proceedings.”

This legislative move, according to Her Lordship, was an implied admission by the Military Government that Section 84, standing alone, lacked constitutional validity. Given that the drafters of the 1999 Constitution deliberately omitted the above provision in the extant 1999 Constitution, Section 84 SCPA cannot stand independently without conflicting with it. It was held as follows:

“In my view, if Section 84 of the S & CPA had existed since 1945 and Decree 107 was promulgated in order to give it constitutional flavour by incorporating it as Section 251(4) of the 1979 Constitution in 1993 by the Military Junta, the law makers definitely did so because they recognised the point that Section 84 of the S & CPA (on its own) was not only inferior to the 1979 Constitution but also in conflict with it. It is therefore my view that standing on its own as it is today, and not being made a provision of the 1999 Constitution, it cannot be validly argued that it is not in conflict with the constitution.”[19]

The second point was the doctrine of separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary. His Lordship emphasized that this principle safeguards each branch of government from encroaching on the functions of the others. He further observed that nowhere in the 1999 Constitution is the authority of the judiciary subordinate to that of the executive. It was held as follows:

“It is trite that separation of power is a constitutional principle introduced to ensure that the three major institutions of the state, namely the legislative, executive and the judiciary are not concentrated in one single body whether in function, personnel or powers. This division ensures that powers of each branch of government are not in conflict with others. The intention behind a system of separated powers is to prevent the concentration of powers by providing for checks and balances. This has been meticulously done in the 1999 constitution (as altered). Nowhere in the 1999 constitution (as altered) have the powers of the judiciary been made subject to the power of the executive.”[20]

His Lordship’s analysis is both compelling and unassailable, and we are in full agreement with its reasoning. One can readily see that Section 84 of the SCPA amounts, at worst, to an unlawful delegation of judicial power, and at best, to sharing judicial authority with a person or body outside the judiciary, thereby undermining the exclusive constitutional role of the courts. It appears that other Justices on the panel overlooked the fact that vesting the Attorney General with the discretion of obeying or not obeying a valid court judgment constitutes a serious affront to the integrity of our constitutional democracy. It weakens the very essence of judicial authority and access to justice. It is unfair that a judgment creditor, having endured the rigors of litigation against the government or its agencies, must then seek the consent of the very adversary to enforce a judgment lawfully obtained. Such a provision erodes public confidence in the rule of law. One of the reasons for its application is that it is an administrative procedure to safeguard the government from embarrassment.[21]

Now, the questions that naturally arise are: What becomes of a judgment creditor if the Attorney General refuses to grant consent? Does the judgment creditor simply walk away empty-handed? We are not unmindful of the fact that in CBN v. Interstella Communications Ltd & Ors,[22] the Supreme Court made an exception to the consent requirement by holding that where the Attorney General is the judgment debtor, consent becomes irrelevant. However, this exception is not enough to safeguard the integrity and supremacy of judicial decisions from executive interference. In our view, if this provision remains in force, monetary judgments against the government will be rendered practically useless in Nigeria. It is our view, that although Ogunwumiju JSC’s opinion did not form the majority decision, it establishes a foundation for the potential judicial invalidation of Section 84 of the SCPA—an approach that may well be adopted in future cases.

4.0 THE WAY FORWARD

4.1 Repealing or Amending Section 84 SCPA

In our considered view, the requirement of obtaining consent to enforce a monetary judgment has long outlived its usefulness and should be repealed by the National Assembly. In the alternative, it ought to be amended to require mere notice rather than consent. Notably, other jurisdictions with the same colonial histories—such as Ghana, Kenya, and India do not have any provision equivalent to Section 84 of SCPA. Even the United Kingdom, from where Nigeria inherited the doctrine, abolished such restrictions by the Crown Proceedings Act of 1947. Yet, Nigeria continues to apply this outdated doctrine, to the detriment of judicial authority and access to justice. Legislative action is needed to remove this problem and ensure that successful litigants can enforce monetary judgments against the government without restrictions.

4.2 Judicial Activism

Judges must embrace judicial activism when the circumstances demand it. They should not remain passive in the face of a law that conflicts with constitutional provisions, given the legislative inaction since its enactment in 1945. Judicial activism is not foreign to our legal system; it is firmly rooted in our corpus juris.[23] Indeed, it was through judicial activism that the Supreme Court of India was able to abolish the colonial doctrine that “the Crown can do no wrong” in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India.[24] It is therefore imperative to allow space for judicial activism, as it can drive the growth of Nigerian law and open new frontiers in our legal system. As Lord Denning aptly observed in Packer v. Packer,[25] “If we never do anything which has not been done before, we shall never get anywhere. The law will stand still while the rest of the world goes on, and this will be bad for the law.” Sadly, in this regard, Nigerian law has remained stagnant since 1945, while the rest of the world has moved forward.

5.0 CONCLUSION

The harmful effects of the consent requirement on enforcing monetary judgments against the government are well-known and need no rehashing. We therefore restate our position that this requirement has outlived its usefulness, as Nigeria is no longer under colonial rule. Our current Constitution has clearly abolished such a practice, and it should therefore cease to be applied since it serves as a shackle on justice delivery. Nigerian courts, including the Supreme Court, have a duty to ensure that their future decisions on this subject matter should uphold the supremacy of the Constitution over any inferior or colonial-era law, which has contributed nothing positive to the development of the nation’s legal system.

[1] Sherrif and Civil Process Act, S. 83.

[2] Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended), S. 287.

[3] Cap. 189 LFN 1958.

[4] Section 155.

[5] Section 156.

[6] Section 274.

[7] Section 315.

[8] Musab Yousufi “The Application of Legal Maxim “King Can Do No Wrong” In the Constitutional Law of UK & USA: An Analytical Study” Global Legal Studies Review V(II) (2020) page 2.

[9] Interpretation Act, S. 45.

[10] (1985) 2 NWLR (Pt. 6) 211.

[11] Page 253, para B-C.

[12] (1985) 3 NWLR (Pt. 11) 71.

[13] Page 79, para B-C.

[14] Ibrahim Imam, “Judicial Activism in Nigeria: Delineating the Extent of Legislative-Judicial Engagement in Law Making” (2015) 15 International and Comparative Law Review 114.

[15] Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended), S. 6(6)(b).

[16] Government of Imo State v. Greeco Construction & Engineering Ltd (Supra).

[17] Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended), S. 1(3).

[18] See Onjewu v. Kogi State Ministry of Commerce & Industry (2003) 10 NWLR (Pt. 827)40; Government of Akwa Ibom State v. Powercom Nig. Ltd (2004) 6 NWLR (Pt. 868) 202 and C.B.N. v. Hydro Air PTY Ltd. (2014) 16 NWLR (Pt. 1434) 482.

[19] Page 148.

[20] Pages 152.

[21] See C.B.N. v. Hydro Air PTY Ltd. (supra).

[22] See (2018) 7 NWLR (Pt. 1618) 294.

[23] See Adegbenro v. Akintola(1963) All NLR 305, Akintola v. Adegbenro (1962) 1 All NLR 442, Williams v. Majekodunmi (1963) 2 SCNLR 26, Council of University of Ibadan v. Adamolekun (1967) NSCC 210, and Lakanmi v. Attorney General of Western Nigeria (1970) NSCC 143.

[24] 1978 AIR 597.

[25] 80 KG pg 226.

Is the Plea of Allocutus a Right or a Privilege in Nigerian Criminal Proceedings? | Isah Bala Garba

By way of introduction, the term allocutus is derived from the classical Latin word allocutio or alloqui, meaning ‘to address or to speak to.’ It is also referred to as allocution, meaning ‘a formal speech.’As such,allocutus or allocution is a formal statement made to the court by the defendant who has been found guilty and is about to be sentenced. This practice originated in England and was recognized by the common law as early as 1682 and Nigeria, being a common law country, also adopted the same. The Supreme Court in the case of Lucky v. State (2016) 13 NWLR (Pt. 1528) held on the meaning of allocutus as follows:‘Allocutus is a plea in mitigation of the punishment richly deserved by an accused person for the offence with which he was charged and for which he was tried and found guilty and convicted accordingly (p. 162, paras. F-G).’ This article examines the legality of allocutus in Nigeria, who makes the plea? When is it made? Must it be granted when made ? Or it can even be overlooked in the entire proceedings?

The legality of allocutus is enshrined in Section 310 of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA), 2015, which provides : ‘Where the finding is guilty, the convict shall, where he has not previously called any witness to character, be asked whether he wishes to call any witness and, after the witness, if any, has been heard, HE SHALL BE ASKED WHETHER HE DESIRES TO MAKE ANY OR PRODUCE ANY NECESSARY EVIDENCE OR INFORMATION IN MITIGATION OF PUNISHMENT in accordance with section 311 (3) of this Act.

(2) After the defendant has made his statement, if any, in mitigation of punishment the prosecution shall, unless such evidence has already been given, produce evidence of any previous conviction of the defendant.’

Subsection (3) of Section 311 referred, state as follows:

‘(3) A court, after conviction, shall TAKE ALL NECESSARY AGGRAVATING AND MITIGATING evidence or information in respect of each convict that may guide it in deciding the nature and extent OF SENTENCE TO PASS on the convict in each particular case, even though the convicts were charged and tried together.[ Capitalization is mine for emphasis]

It’s based on the foregoing that courts do give defendants an opportunity, after exhausting all the stages of criminal trials from arraignment, examination-in-chief, cross-examination, re-examination, written addresses, conviction(finding the defendant guilty for the offense charged) before sentencing to make their plea. The prosecuting counsel also has the opportunity to rebut the plea so as not to make the plea a one-way free ticket; otherwise, accused persons might use it to escape full responsibility. That’s why the prosecution is given the opportunity to make a presentation in rebuttal of the convict’s claim, stating with evidence for example that the convict is not a first time offender, aimed at denying him having the mitigation and which after careful consideration, the courts will thereafter sentence the defendant and bring an end to the criminal trial in the courtroom.

I do not think I sound clear. Let me make myself clearer. If the court pronounced the defendant guilty, before imposing an official sentence, the court normally asks, Do you know of any reason why judgement should not be pronounced upon you? Anyways, consider this example: A young man named Abdul is charged and found guilty of the offence of Grievous bodily harm. While reading judgement, the judge will say, having carefully considered the evidence adduced before this Honourable Court by the prosecuting counsel, it is the firm and unequivocal conviction of this Honourable Court that the defendant is hereby found guilty of the offence charged. After this, the judge will state further: ‘Do you have anything to tell this Honourable Court why you shouldn’t be sentenced to prison?’ Abdul might then say, My Lord, I am very sorry for what I did. This is my first offence; I am an orphan and the breadwinner of the family, with an aged mother alongside five younger ones to take care of. I did this out of desperation but promised never to do it again. Please have mercy and consider a lighter punishment on me. This plea at this stage of trial is what is called: ‘PLEA OF ALLOCUTUS’ and If the court is convinced, the Judge may proceed to state, Having considered the defendant’s plea of allocutus and the circumstances he has presented. While his situation calls for mercy, the law must also be upheld as it is the duty of this Court to balance justice and compassion. As such, the defendant is hereby sentenced to 1 month imprisonment. Let this serve as both a warning and a lesson. I believe you will honor your promise to live a law-abiding life henceforth.

The primary objective of allocutus is to present information that will persuade a Judge to impose a more favourable and lenient sentence than the one defendant ought to be given by law.

Furthermore, there has been debate regarding whether allocutus must only be made by the convict personally or whether it can be made by a lawyer on his behalf. The Court of Appeal in considering who made allocutus In Odunayo v. State (2014) 12 NWLR (Pt. 1420) 1, held that: ‘An allocutus can be made by the convict in person or through a witness to give evidence of previous good character and good works of the convict. Where evidence of good character is given by way of allocutus, the prosecution is also at liberty to produce evidence of previous conviction(p. 25, para. F).’ In addition the supreme court held in approval of a counsel to enter a plea of allocutus for his client who has been convicted for a criminal offence prior to sentencing in the case of Lucky v. State (2016) 13 NWLR (Pt. 1528) Pp. 162-163, paras. H-C) However, the Supreme Court made a U-turn 4 years after in the case of Francis v. F.R.N.(2021) 5 NWLR (Pt. 1769) 398 where per Eko JSC lucidly held inter alia that: ‘THE CONVICT AND NOT THE DEFENCE COUNSEL, pleads his allocutus. In other words, it is for the convict himself to show cause why the prescribed sentence for the offence he was convicted of should not be passed or imposed on him. In the instant case, the allocutus given by the appellant’s counsel was contrary to Rule 20 of the Rules of Professional Conduct for Legal Practitioners, 2007 that prohibits a lawyer as a witness for the client. (Pp. 411, para. F; 412, paras. B-C) [Capitalization is mine for emphasis]

Notwithstanding the above Supreme Court’s pronouncement and which ex facie aligns more with the profession’s ethical behavior, it’s actually not observed in many Nigerian courts because Judges routinely entertain pleas by lawyers on behalf of their convicted clients without issue.

The Supreme Court (In Francis v. FRN), I believe held so to caution and make lawyers to be mindful of their professional boundaries especially during allocutus, considering how the lawyer in that case vehemently tried to overstep the required ethical boundaries such as seeking to tender evidence all in plead of allocutus which the trial court refused to accept and still went further to make it a ground of appeal as if it’s a right.

The ideal is to prepare the defendant for this exercise and let the defendant present the plea personally. The court seeks to hear the voice of the defendant, searching for genuine remorse and sincerity that flow from the heart. At all times, the lawyer should act strictly within authority conferred by the client and if lawyers must do, I normally witnessed, they start by saying: By the authority conferred on me by the Convict, my Lord, I seek to make the plea on his behalf that he is a first-time offender, he’s the breadwinner of the family etc…but not acting as a witness. However, since lawyers making Allocutus on behalf of the defendant has become normalized and accepted practice in the trial courts, I will suggest if the Supreme Court can depart from its decisions in the case of Francis v. F.R.N., as trial courts clearly prefer lawyers making the Allocutus. For example, I witnessed this a few months ago at the Federal High Court, where the Judge did not object to the lawyer who stood up to make the plea on behalf of his client. Allowing this practice has no adverse effect, and lawyers, as masters of the law representing the defendant from the beginning of the case, should be permitted to make the plea on their behalf. The position taken in the case of Lucky v. State, which allows lawyers to make the plea, should be the law. I sell this to the Learned Justices of the Supreme Court. They have a choice not to buy it. I lack the power to question their choice if they choose not to.

Flowing from the foregoing analysis it’s important to note that the plea of allocutus is not a right but a privilege given at the court’s discretion. It is not a fundamental right recognized under constitutional law. The Supreme Court in Chidi Edwin v. The State (2019) 7 NWLR (Pt. 1672) 553 held: ‘Allocutus is not a right in law, neither is it a defence. It is overstretching the constitutional law of fundamental right by attempting to interpret and classify allocutus as a fundamental right under Nigerian law of fair hearing.(p. 565, para. F)’ Also, the court further states: ‘making of allocutus is not mandatory, and its absence does not invalidate the proceedings or sentence (p. 565, paras. E-F; 572, para. D).

In, where the statute prescribes a mandatory sentence indicated by words like ‘shall’ the court ordinarily has no jurisdiction to reduce the sentence or entertain allocutus. For example, the death penalty under Section 221 of the Penal Code admits no discretion, and any sentence other than death upon conviction is a material irregularity. This was given a judicial blessing by the Apex court of the land in the case of State v. John (2013) 12 NWLR RHODES-VIVOUR JSC, held as follows: ‘Once a Judge finds an accused person guilty of culpable homicide under section 221 of the Penal Code, the only sentence he can pronounce is death. A Judge has no jurisdiction to listen to ALLOCUTUS and no discretion to reduce death sentence to a term of years once the accused person has been found guilty under section 221 of the Penal Code.(P. 364, paras. E-F)[Capitalization is mine for emphasis]’

However, where the statute uses language such as ‘is liable to,’ or most often non capital offences the court has some discretion to impose a lesser sentence or fine and may consider allocutus in exercising that discretion. Equally the Administration of Criminal Justice Law 2015 (the ‘ACJL’), a procedural law enacted to supplement the Law, section 316 specifically allows the Court to substitute an imprisonment term for a fine. The Said provision reads: ‘subject to the other provisions of this Section, where a Court has authority under any written law to impose imprisonment for any offence and has no specific authority to impose a fine for that offence, the Court may, in its discretion, impose a fine in lieu of imprisonment.’

Lastly, Before considering allocutus, the court must weigh factors like whether the convict is a first-time offender, the number and age of dependents, terminal illness, genuine remorse, time spent awaiting trial, and evidence of good character. This exercise ensures that the court’s discretion is judicially and judiciously exercised as outlined in Ubiaru v. F.R.N.(2019) LPELR-48252 (CA) Per ANDENYANGTSO, J.C.A (Pp. 31-32, paras. B-E) The trial court must not exceed prescribed statutory limits and should carefully balance justice and mercy through allocutus.

In conclusion, the plea of allocutus in Nigerian criminal proceedings is a privilege, not a right, extended at the discretion of the court and intended for mitigation of sentence rather than exoneration. The plea must be made by the convicted person personally, as the Supreme Court prohibits lawyers from pleading allocutus for their clients citing it is against the profession’s ethical behavior, though practically allowed. Also where statutes prescribed mandatory sentences, allocutus may be ineffective, but where discretion exists, it can shape a fairer outcome.

__________________________________

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

isahbalagarba05@gmail.com or on 08100129131.

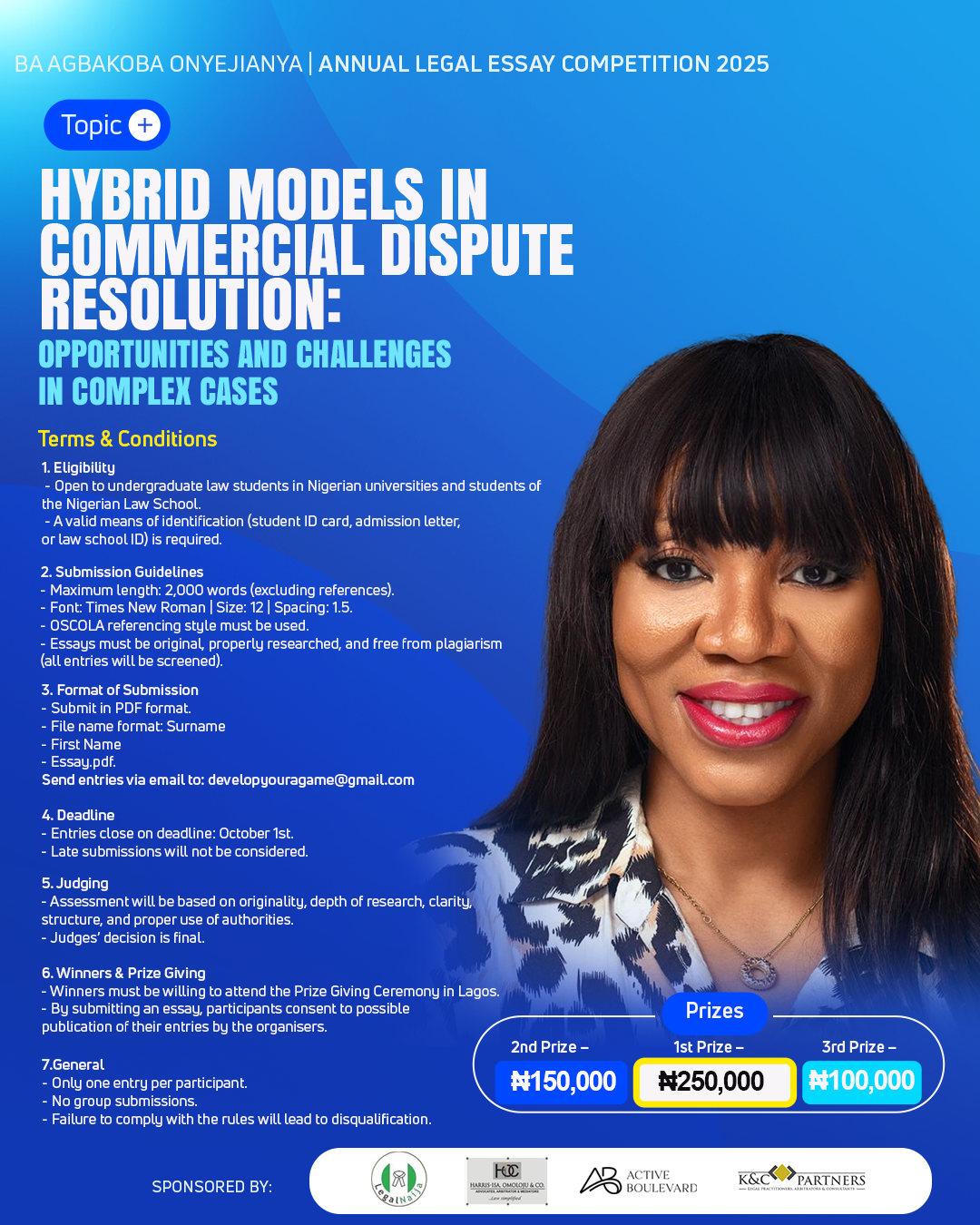

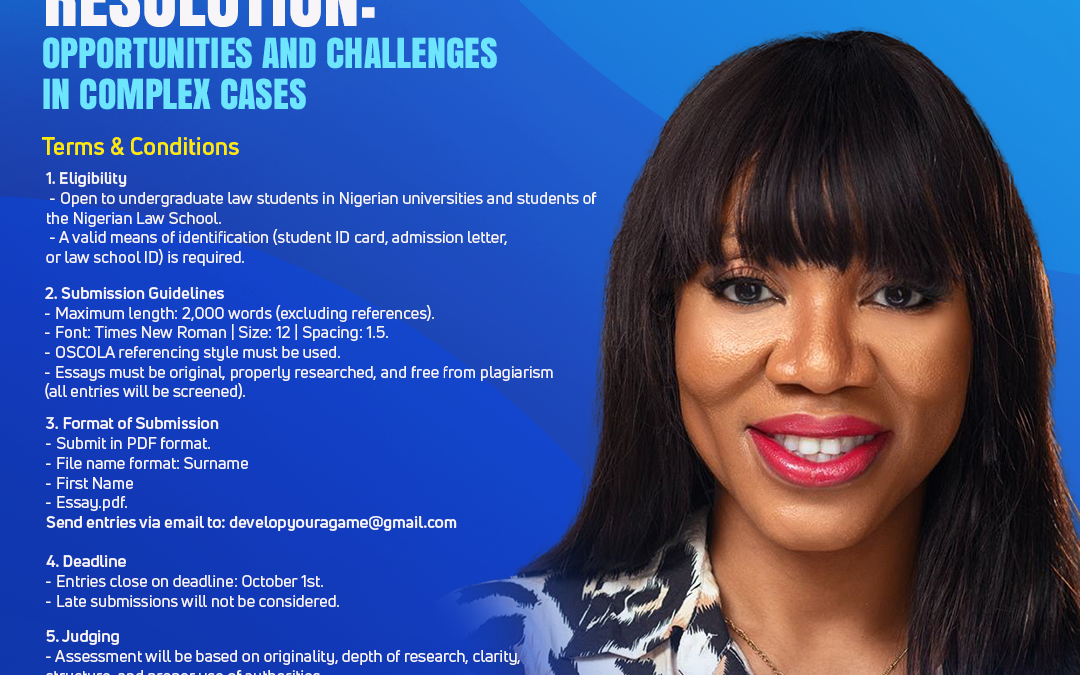

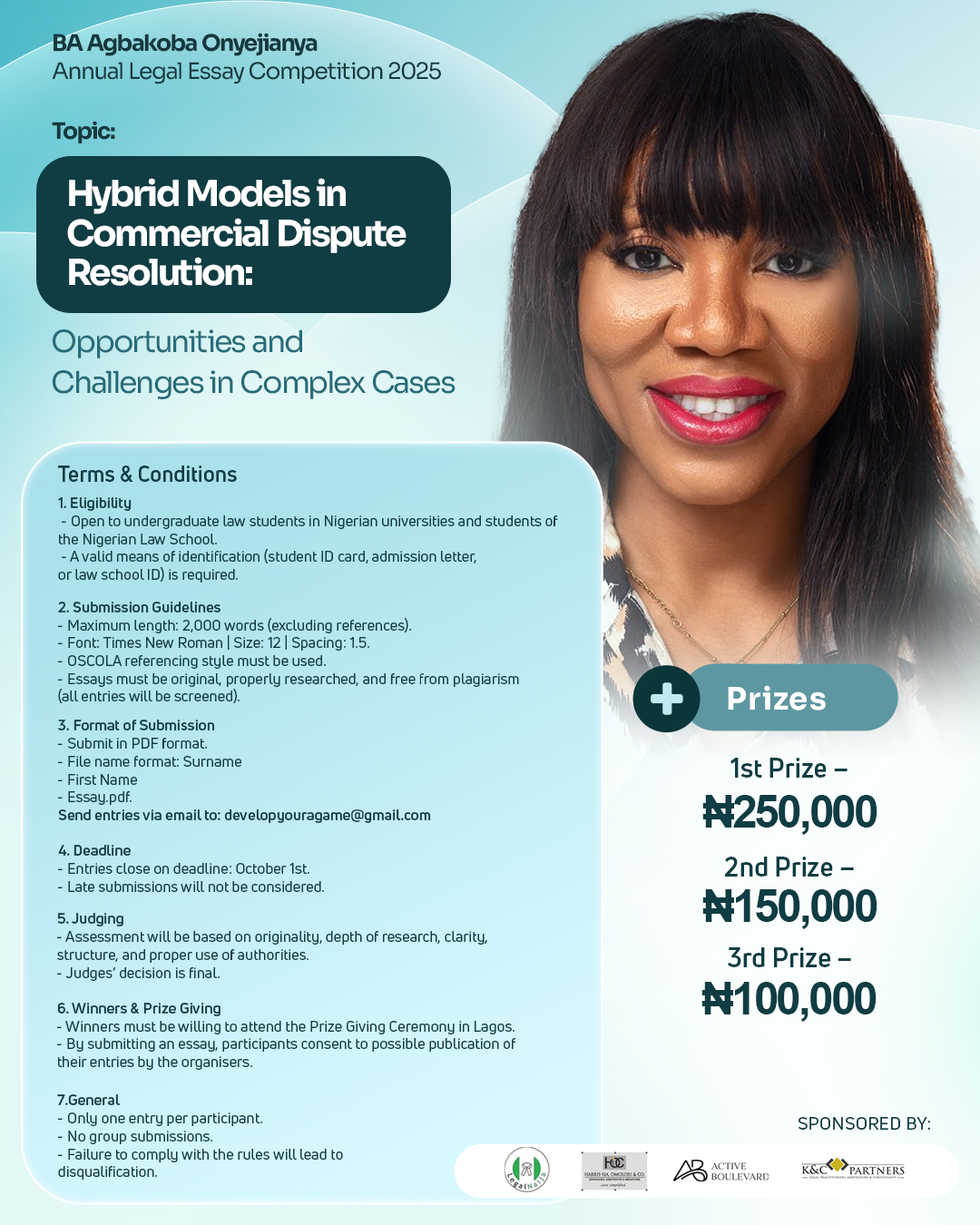

CALL FOR ENTRIES: Agbakoba Onyejiuwa Annual Legal Essay Competition 2025

Are you a Nigerian law student with a sharp mind and a passion for legal innovation? This is your moment to shine.

📌 Topic:

Hybrid Models in Commercial Dispute Resolution: Opportunities and Challenges in Complex Cases

💼 Eligibility:

Open to undergraduate law students in Nigerian universities and students of the Nigerian Law School. Valid student ID or admission letter required.

📄 Submission Guidelines:

– Max 3000 words (excluding references)

– Times New Roman | Size 12 | Spacing 1.5

– OSCOLA referencing format

– PDF format only

– Original, plagiarism-free work (plagiarism test will be conducted)

📅 Deadline:

1st October, 2025

📧 Submit to:

developyouragame@gmail.com

🏆 Prizes:

– 🥇 1st Prize – ₦250,000

– 🥈 2nd Prize – ₦150,000

– 🥉 3rd Prize – ₦100,000

📝 Winning essays may be published on CRWI, Bar & Bench, and other top legal blogs. This is more than a competition—it’s a platform to amplify your voice in the legal community.

Tag your law school crew. Let’s raise the bar. ⚖️

LegalEssayCompetition #AgbakobaOnyejiuwa2025 #Legalnaija #LawStudentsNG #CRWI #BarAndBench

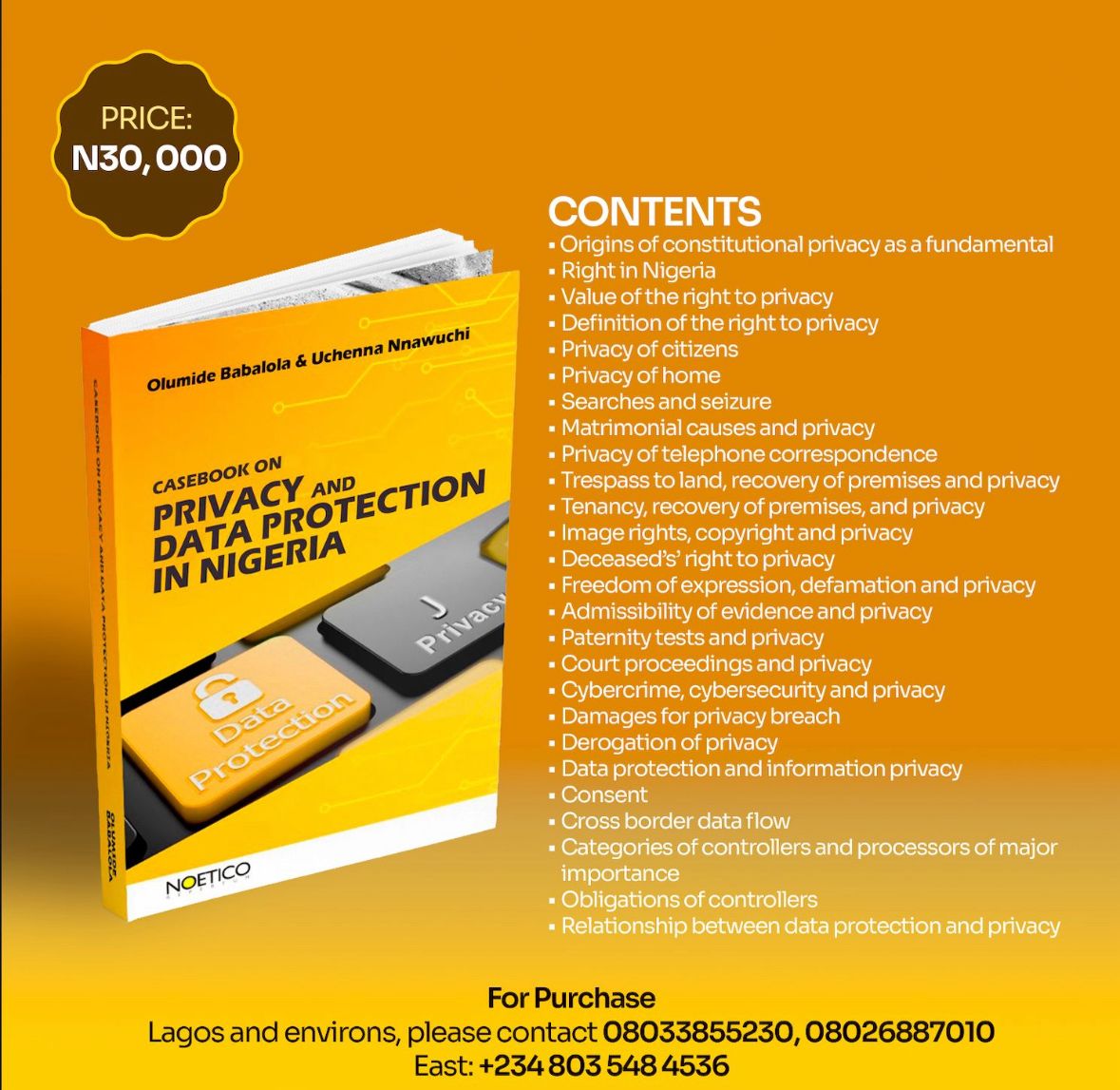

New Release: Casebook on Privacy and Data Protection in Nigeria

The discourse on privacy and data protection in Nigeria has entered a new phase with the publication of a pioneering resource: Casebook on Privacy and Data Protection in Nigeria, authored by leading privacy law scholars Olumide Babalola and Dr. Uchenna Nnawuchi.

Why This Book is Groundbreaking

This casebook is the first of its kind in Nigeria, compiling landmark judicial decisions on privacy and data protection from independence to the present day. It offers far more than a collection of cases—it provides a clear narrative of the evolution, misconceptions, and current realities of privacy jurisprudence in Nigeria.

Highlights include:

A comprehensive and authoritative reference for practitioners, academics, and policymakers.

In-depth analysis of how Nigerian courts have shaped the contours of privacy and data protection law.

A vital resource for students, scholars, and researchers interested in the development of this emerging field.

According to the authors, the book “fills a long-standing gap in Nigerian legal literature and is intended to support both scholarship and practice in a rapidly developing field of law.”

Who Should Read This Book

The Casebook on Privacy and Data Protection in Nigeria is essential reading for:

Legal practitioners seeking practical guidance from judicial precedents.

Academics and students looking for a scholarly yet accessible reference.

Policymakers, regulators, and advocates shaping Nigeria’s data protection landscape.

Now Available;

Following its successful public presentation and scholarly review, the Casebook on Privacy and Data Protection in Nigeria is now available for purchase. This is a unique opportunity to own a resource that will influence teaching, research, practice, and policymaking in one of the most critical areas of contemporary law.

Do not miss the chance to secure your copy of this groundbreaking publication.