by Legalnaija | Oct 18, 2025 | Blawg

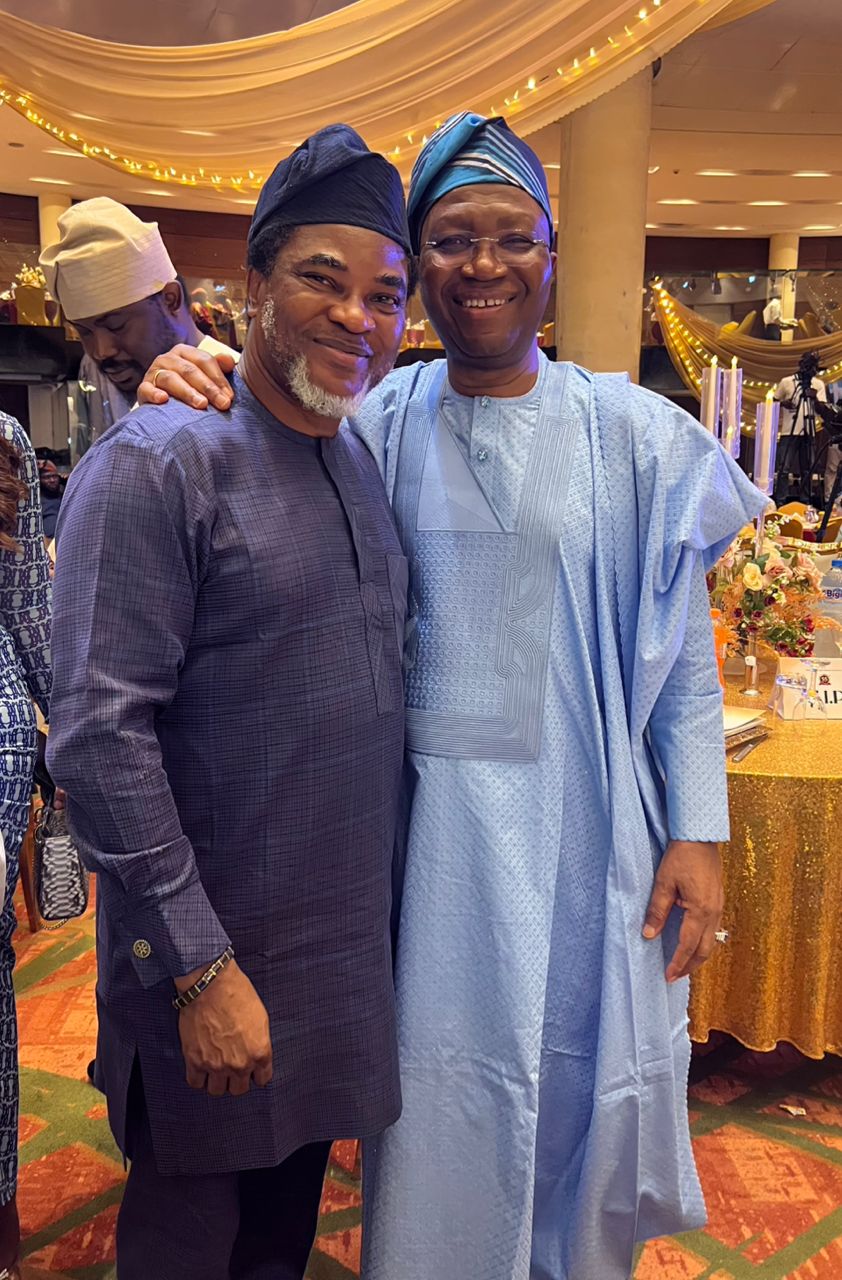

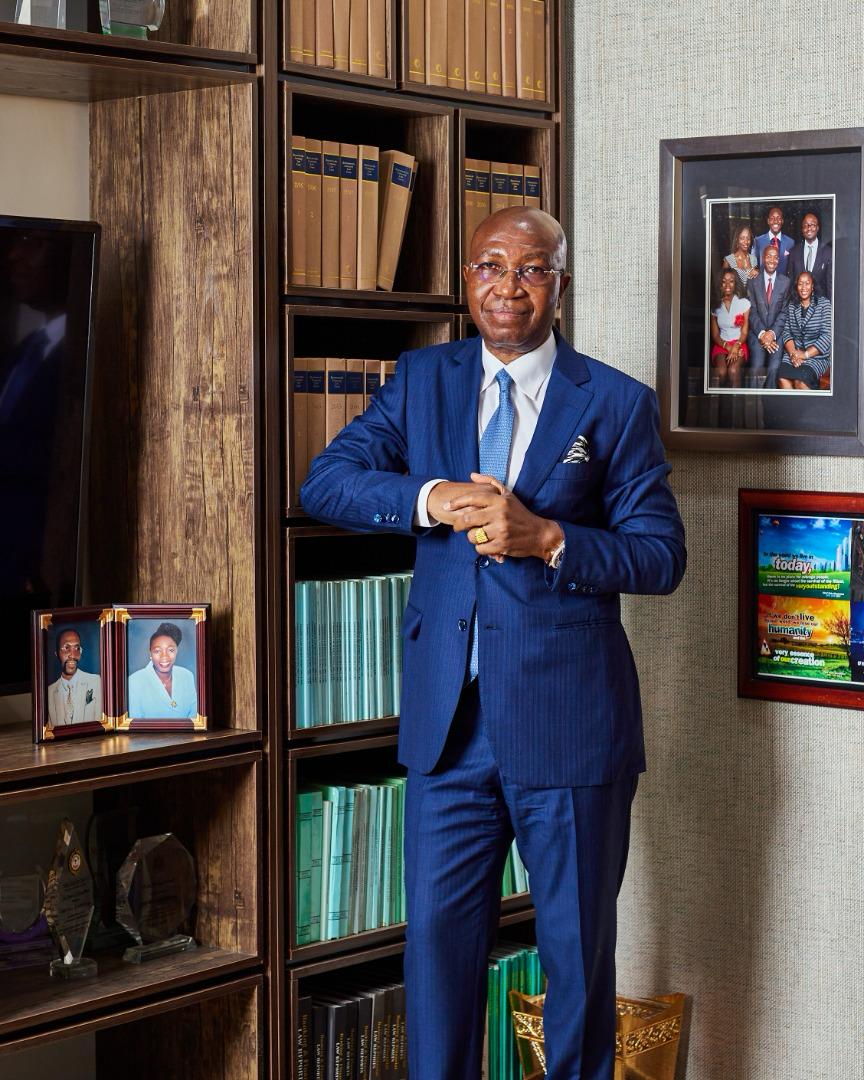

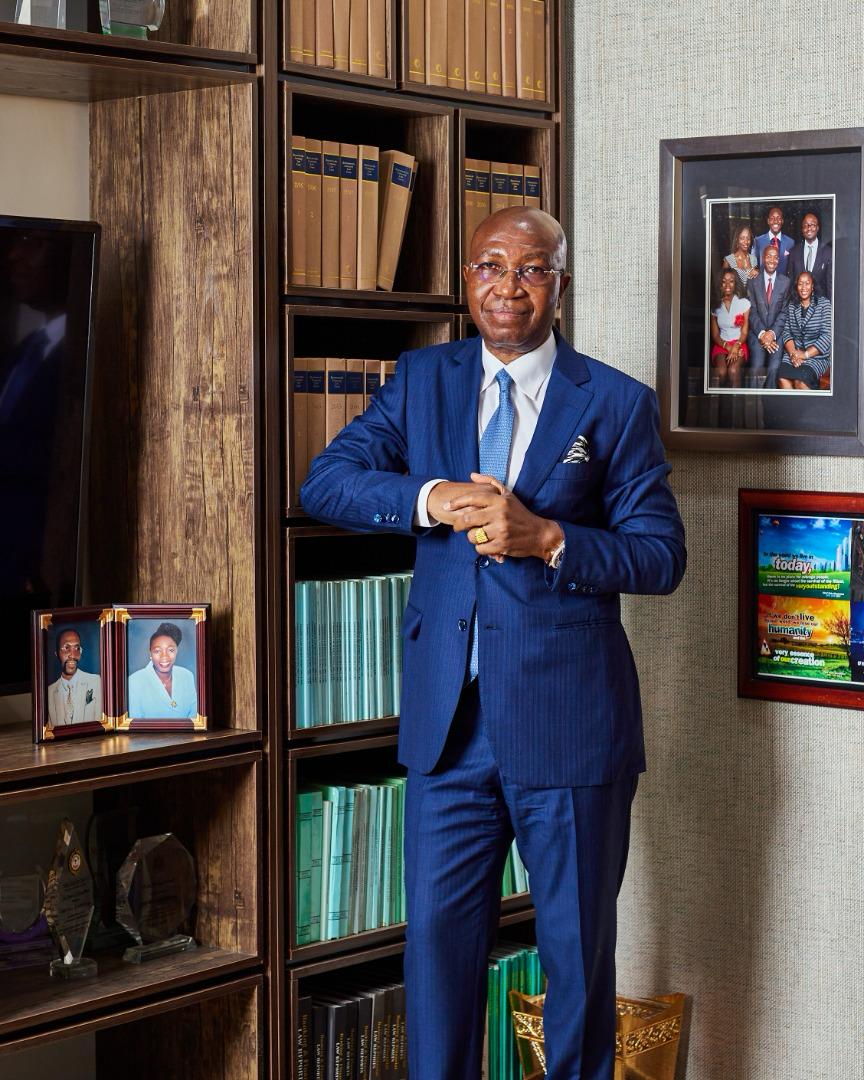

Today, Friday, the 17th of October 2025, another prestigious laurel was bestowed on a man of great accomplishment, honour and valor, the inimitable Chief ‘Wole Olanipekun CFR, OFR, SAN, by the Alumni Association of his Alma Mater, the University of Lagos (UNILAG).

I had the privilege of being in attendance at the 55TH Anniversary Awards & Recognition Dinner where the UNILAG Alumni Association conferred its most prestigious honour, the Platinum Alumni Award (Alumni Lifetime Achievement Award) on Chief Wole Olanipekun, in recognition of his outstanding contributions to the development of the University, the legal profession, nation-building, and his unwavering commitment to excellence, integrity, and service to humanity.

The award ceremony, which held at the Banquet Hall of the Eko Hotels, Victoria Island, Lagos State, brought together eminent personalities from across the legal, academic, political, and business communities to celebrate an illustrious alumnus of the institution whose legacy transcends generations.

A Beacon of Legal Excellence

Chief Wole Olanipekun, CFR, OFR, SAN, a distinguished alumnus of the University of Lagos Faculty of Law, has become a towering figure in the legal landscape of Nigeria and beyond. Since his call to the Nigerian Bar in 1976 and his elevation to the rank of Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) in 1991, Chief Olanipekun has continued to chart new frontiers in legal practice, jurisprudence, and advocacy.

He is widely regarded as one of Nigeria’s most formidable legal minds, having successfully handled landmark constitutional, electoral, and commercial cases. His courtroom mastery, scholarly depth, and principled stance on rule of law have set a gold standard in the profession.

Leadership, Legacy, and Service

Beyond the courtroom, Chief Wole Olanipekun has served Nigeria with distinction. In 1991, he was appointed Attorney General and Commissioner for Justice of Ondo State and served for two years. He was elected President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) in 2002 and served meritoriously till 2004. During his tenure as NBA President, he brought transformative leadership, advocating for judicial reforms, strengthening the independence of the Bar, and defending democratic principles at critical junctures in the nation’s history.

On 19 May, 2024, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu appointed Chief Olanipekun as the Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of the University of Lagos. He had prior to this appointment served as the Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of the University of Ibadan and also still currently serves as the Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of Ajayi Crowther University. As Chairman of Council in both University, Chief Olanipekun showcased his visionary commitment to higher education, institutional governance, selfless service and excellent philanthropic gestures. Under his stewardship, these universities recorded remarkable growth in infrastructure, academic reputation, and ethical leadership. At the University of Ibadan, he constructed and donated to the University a 350-capacity lecture theatre hall for the Faculty of Law. As Chairman of Ajayi Crowther University, he built the Vice Chancellor’s Lodge and other buildings, and constructed roads within the University.

A Philanthropist with a Heart for Education

Beyond philanthropic gestures to academic institutions, Chief Olanipekun is also a man of deep compassion and philanthropy towards humanity. Through the Wole Olanipekun Scholarship Board, he has offered scholarships to hundreds of indigent students, supported community development projects, and championed the empowerment of youth and women, particularly in his native Ikere-Ekiti and across Nigeria. In Ikere-Ekiti, Chief Olanipekun single-handedly built and donated a hospital with state of art facilities, an ultra-modern church and vicarage, a computer laboratory, a High Court building with a well-stocked library amongst several others.

He has consistently demonstrated that success is not just to be celebrated but shared, using his resources, network, and influence to uplift others and build a society anchored on justice and opportunity.

A Proud Ambassador of UNILAG

Chief Olanipekun has remained an active and passionate supporter of his alma mater. His career and values reflect the very ideals that the University of Lagos seeks to instill in its students, that is, critical thinking, intellectual rigour, ethical responsibility, and patriotic service. These values have earned Chief Wole Olanipekun several honours including National Honours of Officer of the Order of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (OFR) and Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (CFR). He is a recipient of several Honorary Doctorate Degrees. Recently, in July 2024, Babcock University conferred on him the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Law and Administration. By the grace of God, on Monday, 20th of October, 2025, Chief Olanipekun will be conferred with yet another Honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D, honoris causa) by the arguably the best private university in Nigeria, the Afe Babalola University, Ado Ekiti (ABUAD).

By conferring on Chief Olanipekun the Platinum Alumni Award, the Alumni Association of the University of Lagos honours not just a legal luminary, but a national treasure whose life’s work continues to inspire, influence, and illuminate paths for future generations. This

Celebrating a Living Legend

The UNILAG community, alumni around the world, and countless beneficiaries of Chief Olanipekun’s mentorship and magnanimity join in celebrating this well-deserved recognition. It is a moment of pride, a symbol of gratitude, and a reaffirmation that true greatness is not only measured by personal accomplishments but by the lives touched and institutions strengthened along the way.

As he receives the Platinum Alumni Award, Chief Wole Olanipekun, SAN, CFR, stands tall, a living testament to what it means to learn, serve, lead, and leave a legacy of excellence.

Congratulations my leader and father, Chief Wole Olanipekun, CFR, OFR. SAN — May your light forever shines brighter.

Adesina Adegbite, FICMC, MCIArb (Bencher)

Secretary, West African Bar Association (WABA), and the Immediate Past General Secretary, Nigerian Bar Association (NBA)

Lagos, Nigeria — 17th, October 2025

by Legalnaija | Oct 16, 2025 | Blawg

Chief Wole Olanipekun To Bag ABUAD Honorary Doctoral, UNILAG Alumni Platinum Award

Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) and former chairman ,Body of Benchers ,Chief Wole Olanipekun ,SAN ,CFR will be receiving double awards from two prestigious universities in Nigeria .

The Nigeria’s foremost Legal Practitioner will be conferred with the Honorary Doctor of Laws, LL. D honoris causa by the fastest growing private university in Africa , Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti(ABUAD) at its forthcoming 13th Convocation ceremonies.

Chief Olanipekun,the Asiwaju of Ikere-Kingdom ,will also deliver the ABUAD’s Convocation Lecture titled: “Nigeria Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, The Imperative of a Sober and Definitive Recalibration” on Monday, at the Alfa Belgore main auditorium .

Similarly , arrangements are in top gear by the leadership of the University of Lagos Alumni Association to bestow the highest honour of the UNILAG ALUMNI PLATINUM Award on Chief Olanipekun .

The UNILAG Alumni event is scheduled to hold on Friday, October 17, 2025 at the Eko Hotels & Suites, Victoria Island ,Lagos under the chairmanship of the Ogbeni Oja of Ijebu land ,Olor’ ogun , Dr Sonny Kuku ,OFR, FAS ,while the Vice President ,Senator Kassim Shettima will be the Special Guest of Honour .

Engineer Ifeoluwa Ayodele,FNSE ,FA Eng, the President Worldwide of the UNILAG Alumni is the Chief Host .

Chief Olanipekun is the Pro Chancellor and chairman of council , University of Lagos .He built a strong reputation across many areas of law (constitutional, arbitration, commercial, etc.).

In 1980, he founded Wole Olanipekun & Co., which has grown into one of Nigeria’s leading law firms with a presence across states .

In 1991, he was appointed Attorney General and Commissioner for Justice of Ondo State, serving for approximately two years

He served as President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) from 2002 to 2004 . In 2007, he was made a Life Bencher (by the Nigerian Body of Benchers)

He has also held roles as Pro-Chancellor / Chairman of Governing Councils at various universities: - University of Ibadan (2004 – 2006) - Ajayi Crowther University, Oyo State .

Chief Wole Olanipekun has been involved in high-profile cases and election petitions, contributing to Nigeria’s jurisprudence and constitutional law development.

by Legalnaija | Oct 15, 2025 | Blawg

THE FACT OF THE CASE BRIEFLY GOES AS FOLLOWS:

The appellant publicly claimed to have discovered a vaccine for HIV and to have cured patients. His claim drew reactions from the 1st and 2nd respondents, who are the Minister of Health and the Medical & Dental Council of Nigeria respectively. Thereafter, the 3rd respondent (Medical & Dental Practitioners Investigating Panel) invited him over alleged professional misconduct. Rather than honouring the invitation, he went to the High Court of the FCT, claiming that the panel was acting as accuser, prosecutor, and judge in its own case, thereby violating his right to fair hearing. The court first granted an interim order but later struck out the motion on jurisdictional grounds.

He furthermore approached the Federal High Court again to enforce his fundamental right being likely to be breached by the panels, arguing that the panels were biased and under the control of the Minister of Health. The court dismissed his case, holding that his complaints and the reliefs he sought were outside the provisions of Chapter IV of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), and were not enforceable under the Fundamental Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules. Dissatisfied, he appealed to the Court of Appeal but failed, and then further appealed to the Supreme Court.

DECISION vis-à-vis ANALYSIS OF THE CASE:

The Supreme Court, per ABBA AJI, J.S.C. (delivering the leading judgment), set aside both the judgments of the trial and lower courts for want of jurisdiction, emphasizing the importance of jurisdiction. The Court held that though the issue and the claims therein are fundamental-right related, as the appellant alleged that his right to fair hearing pursuant to section 36(1) was likely to be breached by the panels, HOWEVER an action against a non-judicial body for enforcement of right to fair hearing cannot be filed under the Fundamental Rights Enforcement Procedure, because section 36(1) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended) provides that: ‘In the determination of a person’s civil rights and obligations, including any question or determination by or against any government or authority, the person shall be entitled to a fair hearing within a reasonable time by a COURT or other TRIBUNAL established by law and constituted in such a manner as to secure its independence and impartiality.’

It’s from the foregoing that the supreme court submitted that the section only dealt with the determination of the civil rights and obligations of a person in cases before a COURT or a TRIBUNAL established as such by law. In other words, the section applies only to proceedings before JUDICIAL BODIES established as such by law and does not extend to all BODIES ACTING JUDICIALLY OR QUASI-JUDICIALLY including domestic or standing ad-hoc tribunals or panels raised departmentally or in an organization to investigate, inquire into, or hear complaints within that department or organization.

In the instance case, the suit by the appellant that the proceedings and decisions of the respondents VIOLATE or are LIKELY TO VIOLATE the PRINCIPLES OF NATURAL JUSTICE against him and his general legal right to fair hearing is a proper and recognizable complaint in law, HOWEVER, the RESPONDENTS NOT BEING COURTS OR TRIBUNALS ESTABLISHED BY LAW, their alleged violation or likely violation of the principles of natural justice against him and his general legal right to fair hearing cannot be brought before the High Court by way of an application for enforcement of fundamental rights pursuant to section 46(1) of the 1999 Constitution and the Fundamental Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules. But the appellant can seek redress for such violation by the ordinary or general processes for seeking remedy for infractions of legal rights and obligations in the High Court.

My Lords further emphasized that the appropriate thing he ought to have done, or the appropriate method to challenge decisions of non-judicial bodies acting judicially or quasi-judicially, is by an application for judicial review by way of a writ of certiorari, prohibition, declaration, or by any of the ordinary methods of legal actions such as writ of summons, originating summons, or originating motion under the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules.

In addition, the Supreme Court further addressed the question of what happens where the issue complaint involves a fundamental right and other multiple issues? It was wittingly and precisely held that: where a set of facts or cause of action gives rise to multiple causes of action, including a breach of fundamental rights, the party so affected would have to bring two different actions at the same time. The appropriate procedures must be adopted for each class of action. One of such actions is by writ of summons according to the provisions of the High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules of the relevant State, and the other by the most suitable originating process, as the case requires, under the Fundamental Rights (Enforcement Procedure) Rules.

Lastly, Supreme Court summed it up with the proper order to be given where the main claim in an action for enforcement of fundamental rights does not fall under Chapter IV of the 1999 Constitution that the proper order the court should make is an order striking out the action on the ground that the court lacks jurisdiction to entertain it. Therefore In the instance case, the trial court and, latter, the Court of Appeal ought to have struck out the appellant’s action after noticing the matter doesn’t fall within the scope of Chapter IV warranting it to be brought under fundamental enforcement procedural rules, and that embarking on making findings was an exercise in futility as it has been a settled and aged long position of law re-echoed in plethora of cases that: All law courts or tribunals, while exercising their powers, must be guided by the general determinants of jurisdiction among which are:

(a) the statute establishing the court/tribunal;

(b) the subject matter of litigation;

(c) the litigating parties;

(d) the procedure by which the case is initiated;

(e) proper service of process;

(f) the territory where the cause of action arose or where the defendant resides; and

(g) the composition of the court/tribunal.

Therefore if any of the above is lacking, the jurisdiction of such Court/tribunal is defective and would undoubtedly lead the whole trial to a nullity.

Briefly put:

Where it’s not a Court of Law or a tribunal established by law that breaches or is likely to breach someone’s fundamental rights such as fair hearing, but rather it’s an administrative or organizational body/panel or commission of inquiry, in other words, it’s a non-judicial body acting judicially or quasi-judicially, the best way to challenge that, is by an application for judicial review by writ of certiorari, prohibition, declaration, or by any of the ordinary methods of legal actions such as writ of summon etc. But where the breach is by a Court of Law or tribunal established by law, then it falls within the scope of Chapter IV and can be filed or brought under the Fundamental Rights Enforcement Procedure Rules. Equally, the appropriate order ought to be given right at the trial court, having found that the claim doesn’t fall within the scope and was brought under fundamental rights enforcement procedure rule instead of bringing it by way of judicial review is to strike it out for lack of jurisdiction and doing anything further was an exercise in futility. As such both the trial court and the Court of Appeal decisions are of no effect whatsoever therefore are liable to be set aside.

N:B: In essence, if the classical case of Garba v. Unimaid were to come up today, it might have faced a procedural challenge for being filed under fundamental rights enforcement rather than judicial review.

Funny enough, I did a moot in the just concluded semester on a fact almost similar to Garba v. Unimaid. But I refused to follow the mode adopted by the learned counsel in that case: filing a suit for enforcement of fundamental rights. I went by way of judicial review. I could remember I consulted two of my seniors Abubakar Abdullahi Raji, Senior Advocate of Bayero University Kano (SABUK), and Salihu Haruna, SABUK about it, and they said I should give it a try, so I filed an ex parte motion for leave alongside my main application for judicial review. As if I knew this Supreme Court pronouncement was coming to validate it.

__________________________________________

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

isahbalagarba05@gmail.com or on 08100129131

by Legalnaija | Oct 15, 2025 | Uncategorized

Introduction

Defamation remains one of the most sensitive aspects of Nigerian law, a space where personal reputation and freedom of expression constantly meet and sometimes collide. The law recognizes that while every person is entitled to protect his or her good name, society must also preserve the freedom to speak the truth, express honest opinion, and hold others accountable. It is against this background that both civil and criminal defamation have developed under Nigerian law, each with distinct purposes and procedures.

Understanding Civil and Criminal Defamation

Civil defamation arises under the common law of tort and is designed to compensate a person whose reputation has been unjustly damaged by another’s false statement. Criminal defamation, on the other hand, is a statutory offence under Sections 373–381 of the Criminal Code Act (applicable in Southern Nigeria) and Sections 391–395 of the Penal Code (applicable in Northern Nigeria). Its aim is to protect public peace and order by punishing statements capable of provoking violence or widespread hatred.

The Court of Appeal in Okotcha v. Inspector-General of Police (2019) LPELR-47848 (CA) explained that civil defamation is concerned with personal injury to reputation, while criminal defamation concerns the peace of the public. The dividing line, therefore, lies in the intention behind the publication and its likely effect on society. A publication that merely injures an individual’s reputation is civil, but one that tends to incite public disorder or hatred crosses into the criminal sphere.

In both civil and criminal defamation, the parties and the remedies sought differ fundamentally in purpose and consequence. In civil defamation, the action is a private one between the plaintiff, whose reputation has been injured, and the defendant, who made or published the defamatory statement. The remedy here is primarily compensatory damages, injunctions, or an apology to restore the injured person’s reputation. In contrast, criminal defamation is a public prosecution instituted by the State through the police or the Attorney-General against the accused person for an offence that threatens public order. The remedy in this case is punitive, involving fines or imprisonment as provided under the Criminal and Penal Codes. As the Court of Appeal held in Okotcha v. I.G.P. (Supra). The accused person here, enjoys the shade of constitutional safeguards of Presumption of innocence as guaranteed under Section 36(5) of the 1999 Constitution, and failure to establish any of the fundamental ingredients of offence alleged will occassion into failure of the charge and will lead to the discharge of the defendant.

Improper Invocation of Police Powers

It has become increasingly common to see individuals rushing to the police over issues that are clearly civil in nature, including defamation. Such practices have no basis in law. The Police Act, 2020, in Section 4, clearly defines the duties of the Nigerian Police Force as:

“The prevention and detection of crime, the apprehension of offenders, the preservation of law and order, the protection of life and property, and the due enforcement of all laws and regulations.”

Nowhere in the Act is the police empowered to intervene in purely civil disputes or to enforce personal rights. In Onagoruwa v. State (1991) 5 NWLR (Pt. 193) 593, the Court of Appeal described the police in words that still echo today:

“They are custodians of legality, not instruments of oppression. Their duty is to enforce the law, not to manufacture offences where none exist.”

When the police act outside these limits, they act ultra vires, beyond their lawful authority. Any proceeding or prosecution founded on such misuse is void. Moreover, such conduct wastes the court’s precious time and erodes public trust in both the law and its institutions. Courts have consistently warned against the abuse of their process, as seen in A.G. Anambra State v. Okeke (2002) 12 NWLR (Pt. 782) 575, where the Supreme Court cautioned that the judicial process must never be used as a tool for harassment or revenge.

Ingredients of Defamation

For civil defamation, the claimant must prove three essential elements:

- That the statement complained of is defamatory;

- That it refers to the claimant; and

- That it was published to a third party.

For criminal defamation, the prosecution must go further to prove beyond reasonable doubt that:

- The accused published defamatory matter;

- The publication referred to the complainant;

- It was false;

- It was made with intent to harm the complainant’s reputation; and

- It was not protected by any lawful defence or privilege.

These requirements underscore the seriousness with which the law views defamation, especially when it borders on criminal conduct.

Defences to Defamation

The law is not blind to the need for fairness. It recognizes that people should not be punished for speaking the truth, expressing honest opinions, or communicating in good faith. The defences available to a person accused of defamation ensure that justice does not silence legitimate expression.

Defences in Civil Defamation

- Justification (Truth)

The truth of a statement is an absolute defence. No one has the right to complain about a statement that is substantially true. In Oruwari v. Osler (2013) 5 NWLR (Pt. 1348) 535, the Court of Appeal held that “truth is a complete defence to defamation, for the law does not protect a man from the publication of that which is true about him.”

- Fair Comment on Matters of Public Interest

A person may freely express an honest opinion on a matter of public importance, provided it is based on facts that are true and expressed without malice. The Court of Appeal in Sketch Publishing Co. Ltd v. Ajagbemokeferi (1989) 1 NWLR (Pt. 100) 678 held that fair comment must be an opinion any reasonable person could hold, not a reckless assertion.

- Qualified Privilege

Certain communications made in the performance of a duty or in the protection of a legitimate interest are privileged. This defence will fail only where malice is proved. In Emeagwara v. Star Printing & Publishing Co. Ltd (2000) 14 NWLR (Pt. 688) 372, the court affirmed that a statement made in good faith, in discharge of a duty, is privileged.

- Absolute Privilege

Some occasions are so vital that the law gives complete immunity from liability, even if the words are false or malicious. Examples include statements made in judicial proceedings, legislative debates, or official acts performed in the line of duty. The case of R v. Governor of Lagos, Ex parte Roderick (1970) NMLR 204 recognized this principle.

- Innocent Dissemination

Those who unknowingly distribute defamatory material such as printers, booksellers, or internet service providers are protected where they had no reason to suspect the material was defamatory. The English case of Byrne v. Deane (1937) 1 KB 818, which has been followed in Nigerian courts, illustrates this principle.

- Apology and Retraction

Though not a full defence, an apology or retraction may mitigate the damages awarded. The Defamation Law of Lagos State (Cap. D5, Laws of Lagos State 2015) recognizes this mitigation when the apology is made promptly and sincerely.

Defences in Criminal Defamation

- Truth and Public Benefit

Under Section 375 of the Criminal Code and Section 392(2) of the Penal Code, a statement is defensible if it is true and it was for the public good that it be published. Both elements must coexist, a true statement published maliciously and without public benefit can still be criminal.

- Privileged Publications

Sections 376 of the Criminal Code and 393 of the Penal Code recognize privilege for publications made in judicial, legislative, or official proceedings, or fair and accurate reports thereof.

- Fair Comment on Public Affairs

The defence of fair comment applies where the statement represents a genuinely held opinion on a matter of public concern, made without malice. This principle was reaffirmed in Guardian Newspapers Ltd v. Ajeh (2011) 10 NWLR (Pt. 1256) 574.

- Innocent Publication

Under Section 377 of the Criminal Code, a person is not liable if they neither knew nor intended the publication to be defamatory and took reasonable care to prevent it.

- Consent of the Aggrieved Party

Where the publication was made with the consent of the person defamed, it cannot constitute an offence. This is recognized under Section 378 of the Criminal Code.

Misuse of Judicial Process and Consequences

The courts have consistently warned against the misuse of their time and process. Bringing frivolous or unfounded defamation claims, or using the police to pursue personal grudges, is viewed as a serious abuse. In Saraki v. Kotoye (1992) 9 NWLR (Pt. 264) 156, the Supreme Court defined abuse of court process as using judicial procedure for purposes it was not intended.

Such misuse can attract punitive costs, dismissal of the case, and in extreme cases, disciplinary action against the erring party or counsel. The court’s time is too valuable to be spent on matters that, as judges often say, “go to no issue.” The justice system exists to correct genuine wrongs, not to satisfy vanity or vendetta.

Conclusion

The law of defamation in Nigeria is built upon balance, the balance between protecting the dignity of individuals and upholding the freedom of expression vital to democracy. Every lawyer, journalist, and citizen must understand this delicate equilibrium.

Before rushing to court or the police over alleged defamation, one must pause and ask himself, Is this truly a matter for criminal law, or simply a civil grievance? The misuse of police powers and the abuse of court processes only weaken the integrity of our justice system.

As the courts have often reminded, the law is not a weapon for oppression but an instrument of order and fairness. Defamation law, properly understood, protects truth, honesty, and responsible expression not malice, ego, or misuse of authority.

Amb. Ibrahim Muhammad Usman is a law graduate, advocate of intergenerational justice and equity, a passionate voice for Sustainable Development Goals, Inclusive policy and good governance, AI safety and governance in Africa, and climate justice. He can be reached via imuhammadusman66@gmail.com or 08145101965.

Amb. Ibrahim Muhammad Usman is a law graduate, advocate of intergenerational justice and equity, a passionate voice for Sustainable Development Goals, Inclusive policy and good governance, AI safety and governance in Africa, and climate justice. He can be reached via imuhammadusman66@gmail.com or 08145101965.

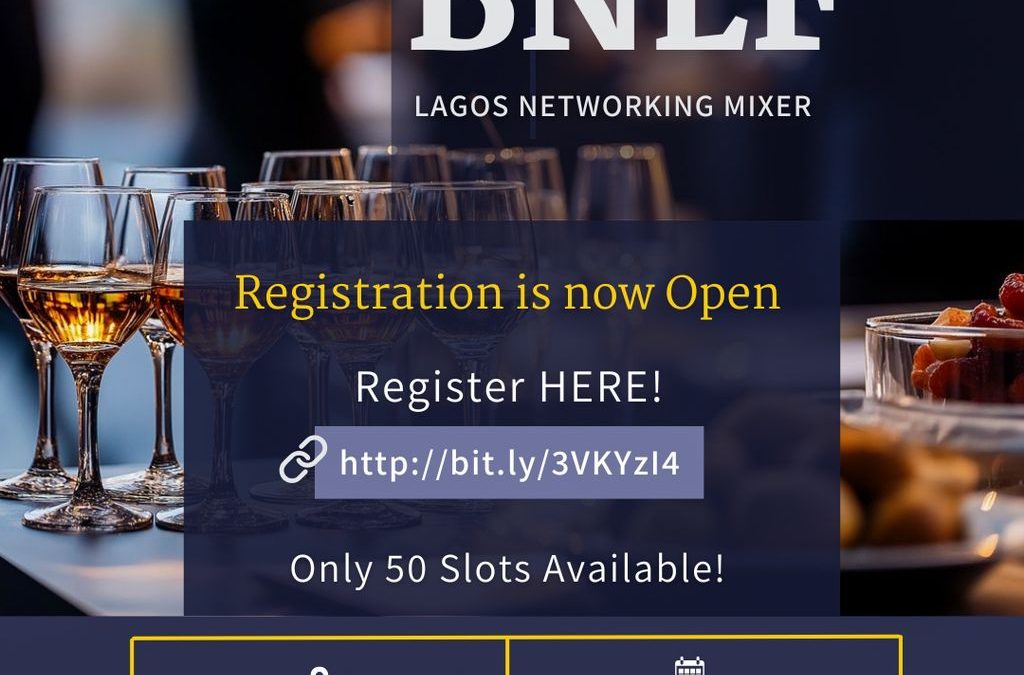

by Legalnaija | Oct 8, 2025 | Blawg

Building Connections in Lagos: Join the BNLF Networking Mixer

In today’s fast-paced legal landscape, relationships matter just as much as expertise. That’s why the British Nigeria Law Forum (BNLF) is excited to invite legal professionals, enthusiasts, and industry stakeholders to the BNLF Lagos Networking Mixer — an evening designed to foster meaningful connections, spark insightful conversations, and grow your professional network.

Whether you’re a seasoned lawyer, a budding legal entrepreneur, or simply passionate about the law, this event offers a unique opportunity to engage with like-minded individuals in a relaxed and inspiring setting.

📍 Event Details

– Venue: Grey Matter Social Space, Victoria Island, Lagos

– Date: Thursday, 23rd October 2025

– Time: 6 PM

– Slots: Limited to just 50 attendees

From policy discussions to practice tips, the mixer promises a dynamic blend of professional exchange and social interaction. Expect to meet thought leaders, innovators, and peers who are shaping the future of law in Nigeria.

🎟️ How to Attend!

Secure your spot now via Tix Africa. With only 50 slots available, early registration is highly recommended.

Follow this link to register!

https://tix.africa/discover/bnlflagosnetworkingmixer

Let’s build a stronger, more connected legal community — one conversation at a time.

#BNLF2025 #Legalnaija #NetworkingMixer #LagosLawyers #LegalCommunity #BNLFEvents

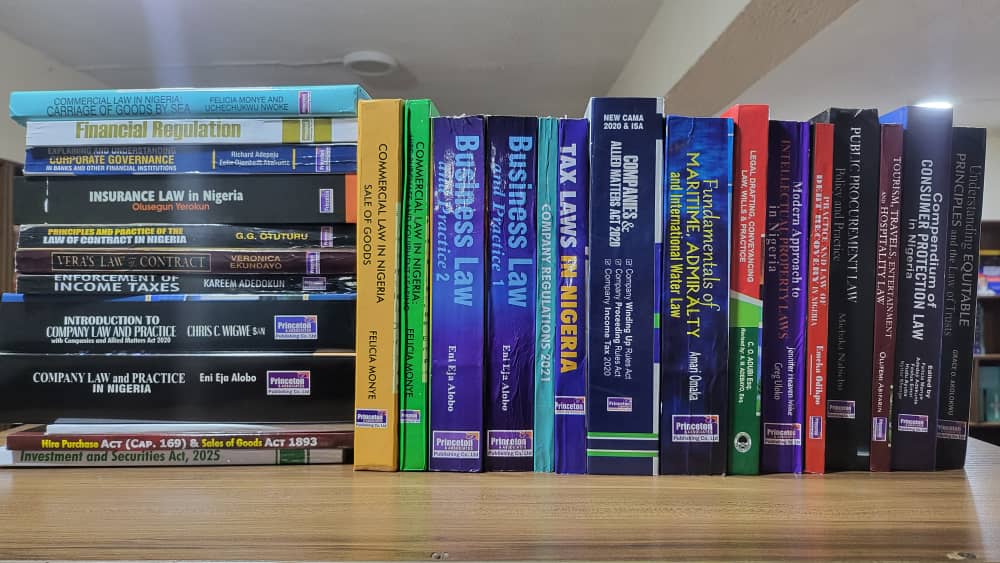

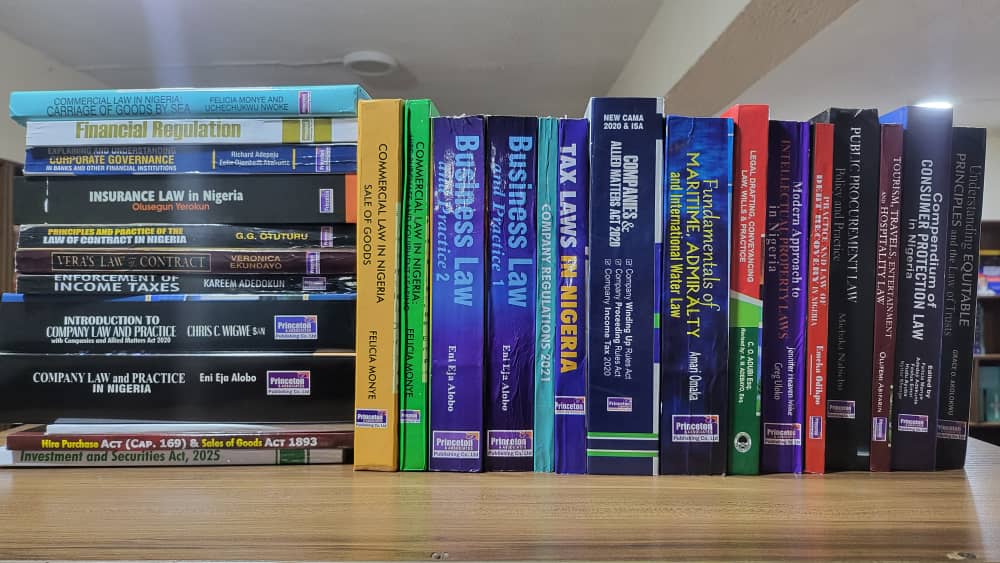

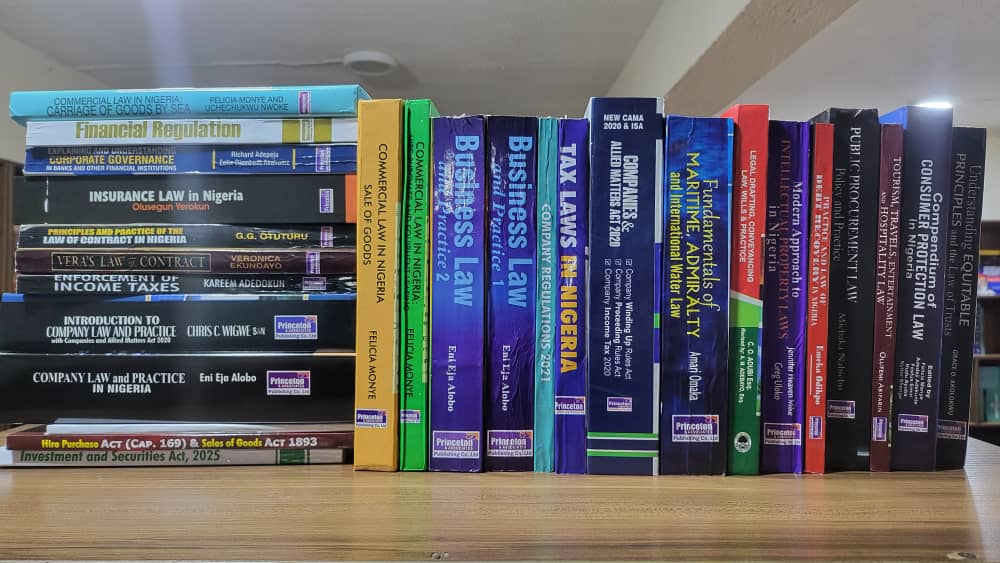

by Legalnaija | Oct 8, 2025 | Blawg, Book

In the fast-paced world of business law, staying ahead means staying informed. Whether you’re advising multinational corporations, negotiating complex contracts, or navigating regulatory frameworks, the right resources make all the difference.

That’s why the Legalnaija Bookstore has curated the Business Law Bundle—a powerhouse collection of 27 essential titles tailored for corporate and commercial lawyers in Nigeria. From foundational statutes to advanced legal commentary, this bundle is your gateway to mastering the intricacies of business law.

🔍 What’s Inside the Bundle?

Here’s a look at the titles included:

- Commercial Law in Nigeria – Carriage of goods by sea

- Financial Regulation Act

- Explaining and Understanding Corporate Governance in Banks and other Financial Institutions

- Insurance Law in Nigeria

- Principles and practice of the Law of Contract in Nigeria

- Vera’s Law of Contract

- Enforcement of Income Taxes

- Introduction to Company Laws and practice in Nigeria

- Company Law and practice in Nigeria

- Data protection Act

- Hire Purchase Act

- Investment & Securities Act

- Commercial Law in Nigeria: Sale of Goods

- Commercial Law in Nigeria: Hire Purchase and Equipment Leasing

- Business Law 1

- Business Law 2

- Company Regulations 2021

- Tax Laws in Nigeria

- Companies and Allied Matters Act

- Fundamentals of Maritime, Admiralty and International Water Law.

- Legal drafting, conveyancing law, Wills and practice

- Modern Approaches to Intellectual Property Law in Nigeria

- Practice and Recovery in Nigerian Law

- Public Procurement Law

- Tourism, Travels, Entertainment and Hospitality Law.

- Compendium Of Consumer Protection in Nigeria

- Understanding Equitable Principles and the Law of Trusts.

Whether you’re a seasoned practitioner or a rising star in the legal field, the Business Law Bundle equips you with the tools to thrive.

🛒 Available Now at Legalnaija Bookstore

Ready to elevate your legal library? Visit the Legalnaija Bookstore and grab the Business Law Bundle today for N230,000 only via this link – https://legalnaija.com/product/business-law-bundle/

Your clients—and your career—will thank you.

For more information, please contact us via email at hello@legalnaija.com or WhatsApp 09029755663.

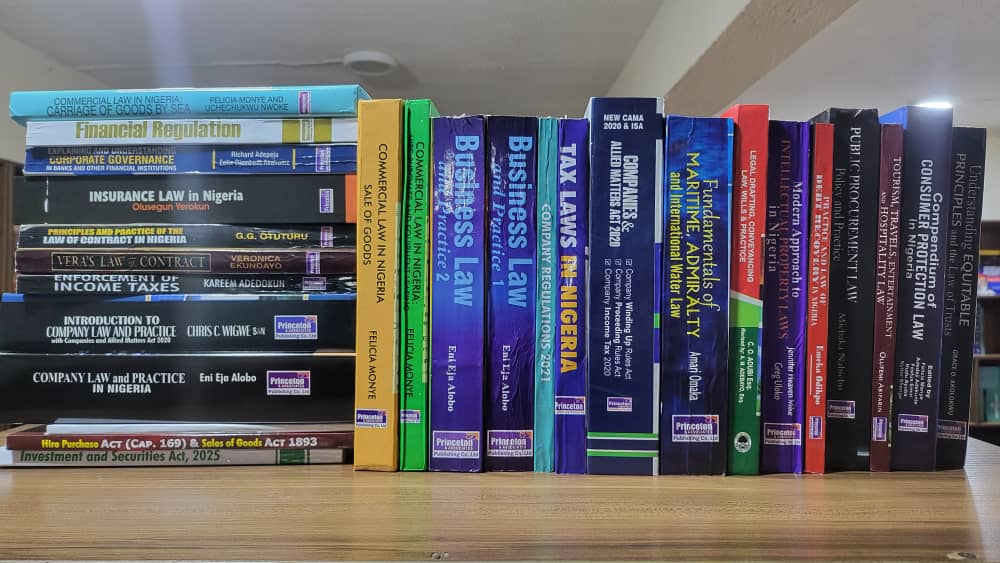

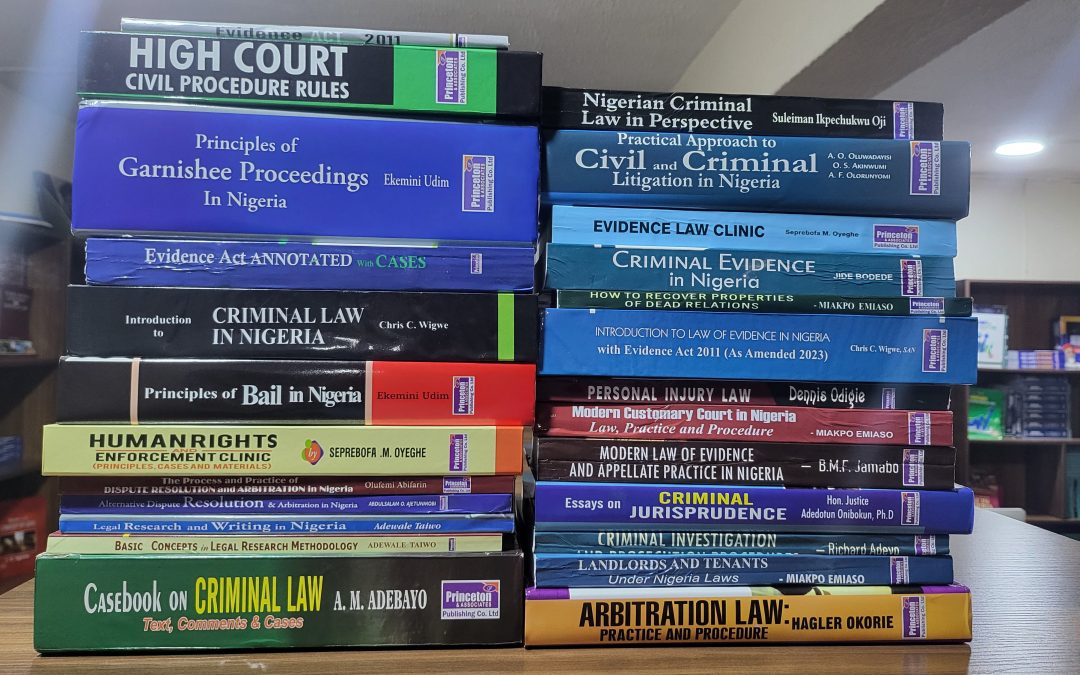

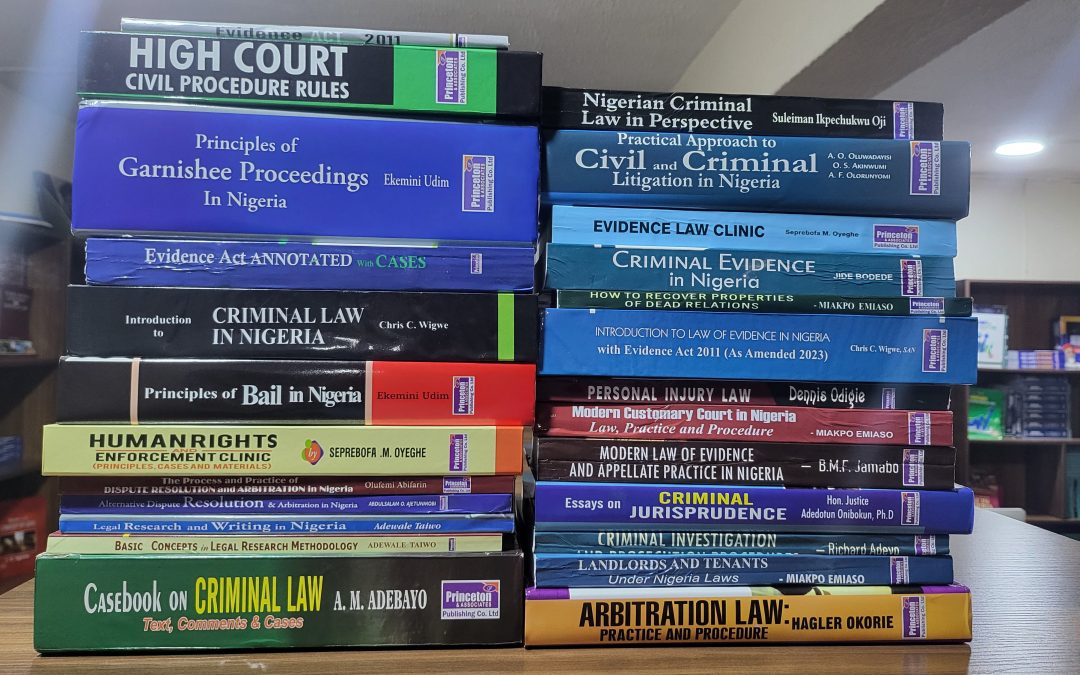

by Legalnaija | Oct 7, 2025 | Blawg

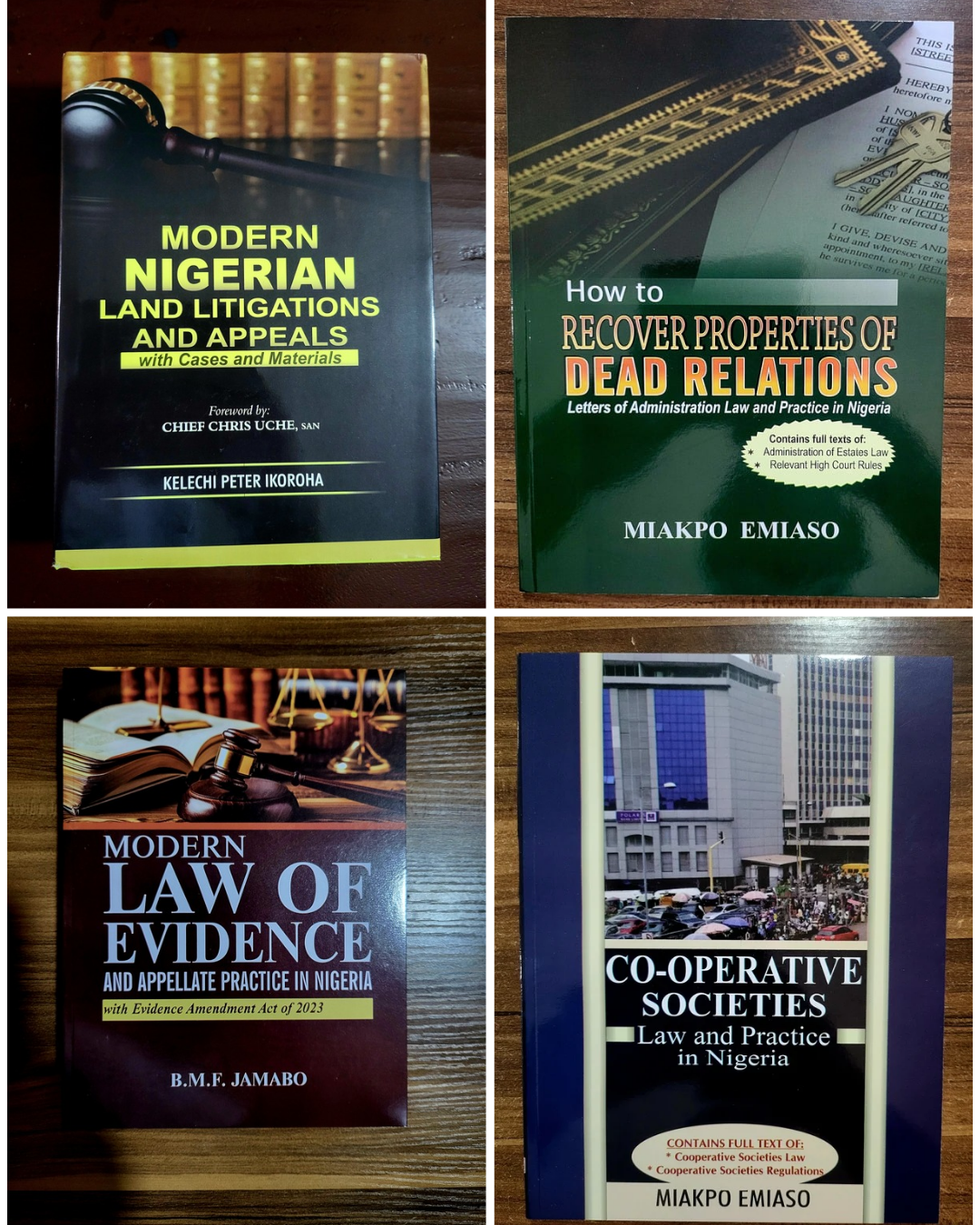

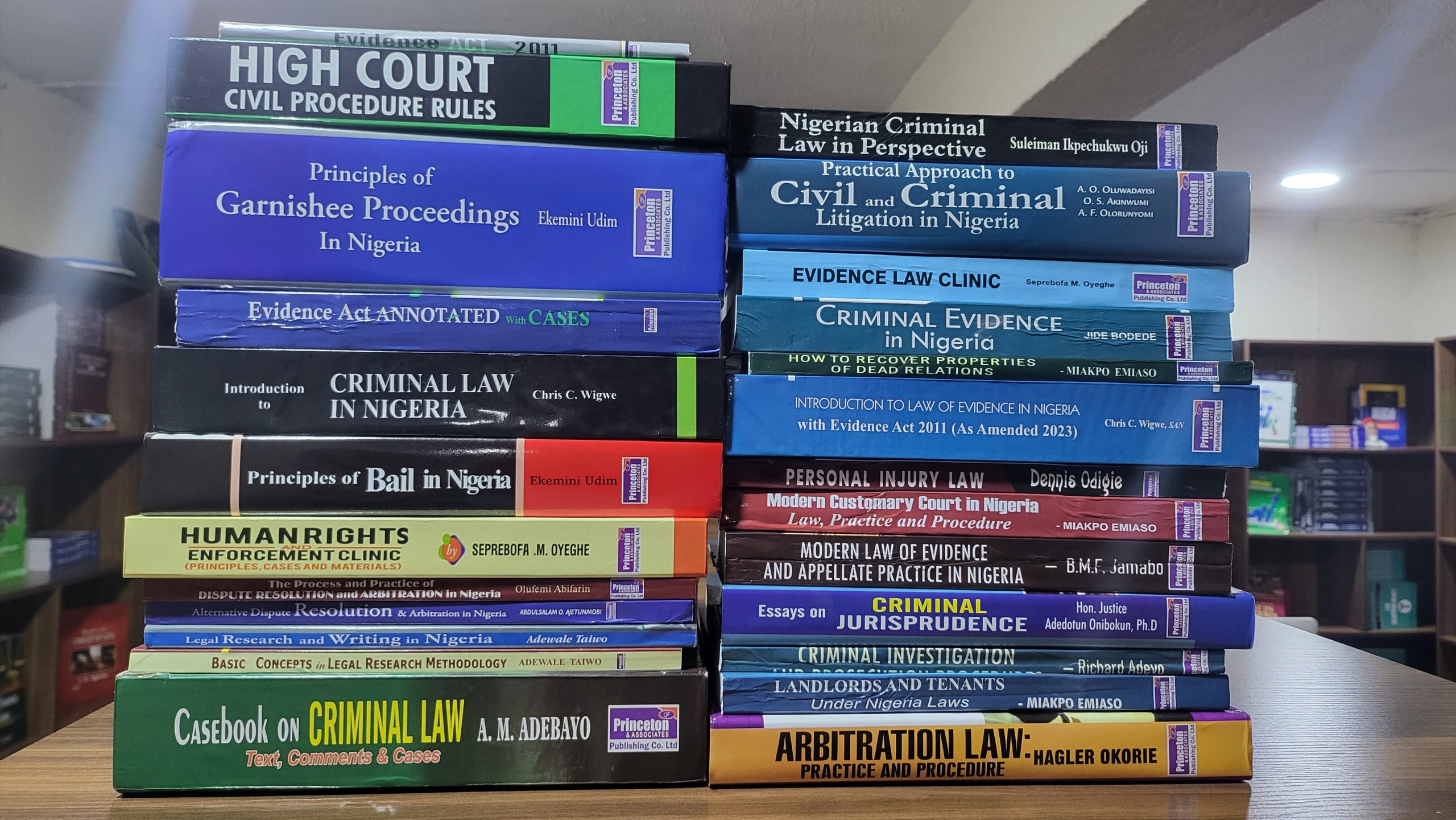

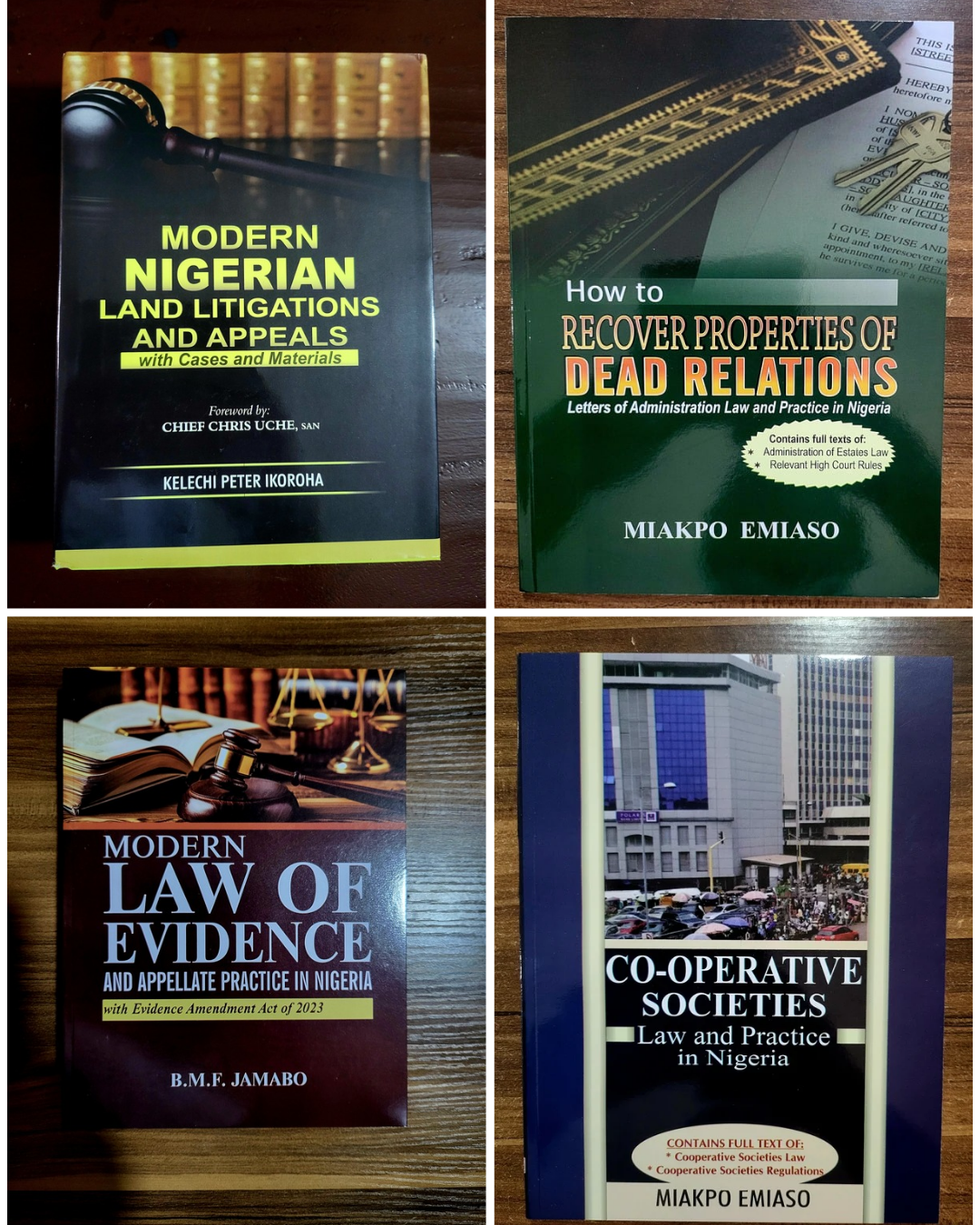

In the fast-paced world of litigation and dispute resolution, knowledge isn’t just power — it’s your strongest argument in court. Whether you’re a seasoned advocate or a rising associate, your library should be as sharp as your cross-examination skills.

That’s why Legalnaija Bookstore has curated a powerful collection of 26 essential titles for lawyers who live and breathe courtroom drama, arbitration tables, and the pursuit of justice.

Why This Collection Matters:

– Covers criminal and civil litigation, evidence law, ADR, and legal research

– Features renowned Nigerian authors and texts tailored to our legal system

– Perfect for law firms, solo practitioners, and law students preparing for practice

What You’ll Find Inside:

From classics like Principles of Evidence to practical guides like How to Recover Properties of Dead Relations, this collection dives deep into:

– Criminal law theory and casebooks

– Civil procedure and trial strategy

– Bail, prosecution, and appellate practice

– Arbitration and ADR frameworks

– Legal writing and research methodology

– Customary court insights and landlord-tenant law

Who Should Grab This Collection?

– Litigators looking to sharpen their advocacy

– Law firms building internal libraries

– Young lawyers preparing for court appearances

– Legal researchers and academics

– Judicial officers seeking reference materials

Lost of books include;

1. Casebook on Criminal Law by A.M. Adewale

2. Evidence Act 2011

3. High Court Civil Procedure Rules

4. Principles of Criminal Law

5. Casebook on Law of Contract

6. Criminal Law Annotated with Cases

7. Introduction to Criminal Law by Chris Ugwueze

8. Principles Governing Bail in Nigeria

9. Human Rights and Enforcement of Criminal Law

9. The Process and Practice of Dispute Resolution and Arbitration in Nigeria

10. Alternative Dispute Resolution and Arbitration in Nigeria

11. Legal Research and Writing in Nigeria

12. Basic Concepts in Legal Research Methodology

13. Casebook on Criminal Law

14. Nigerian Criminal Law in Perspective –

15. Practical Approach to Civil and Criminal Litigation in Nigeria

16. Evidence Law Clinic

17. Criminal Evidence in Nigeria

18. How to Recover Properties of Dead Relations

19. Introduction to Evidence Law in Nigeria

20. Personal Injury Law

21. Modern Customary Court in Nigeria

22. Modern Law of Evidence and Appellate Practice in Nigeria

23. Essays on Criminal Justice

24. Criminal Investigation and Prosecution Proceedings

25. Landlord and Tenants under Nigerian Laws

26. Arbitration Law: Practice & Procedure

🛒 Available Now on Legalnaija Bookstore

Don’t wait until your next court date to upgrade your legal arsenal. Visit the Legalnaija Bookstore today and explore this curated selection — because every great lawyer deserves a great library.

With over 100 successful deliveries to lawyers and law firms outside Lagos alone. You can be sure to get your books delivered speedily!

Order these collection of books tagged Litigation and ADR Expert Bundle. Visit this link to order all the books for 260,000 Naira only https://legalnaija.com/product/litigation-and-adr-expert-bundle/

You can also visit the bookstore for other books in different areas of Practice you are interested in! www.legalnaija.com/store

For information email hello@legalnaija.com or WhatsApp 09029755663.

by Legalnaija | Oct 5, 2025 | Blawg

Why You Need a Lawyer Before Wahala Starts: The Power of Preventive Legal Representation

Why You Need a Lawyer Before Wahala Starts: The Power of Preventive Legal Representation

In Nigeria, we often hear the phrase “I no go court unless wahala dey.” It’s a common sentiment—many people only think of lawyers when trouble has already landed. But what if I told you that having legal representation before problems arise could save you time, money, and serious stress?

Welcome to the world of preventive lawyering—a smart, proactive approach to life and business that every Nigerian should embrace.

Order here legalnaija.com/store

Think Ahead, Not After

Whether you’re signing a tenancy agreement, starting a business, entering a partnership, or even getting married, legal advice is not a luxury—it’s a necessity. Lawyers are trained to spot red flags in contracts, decode legal jargon, and protect your interests before you say “yes” to anything that could come back to bite you.

Imagine signing a land purchase agreement without verifying the title documents. Or launching a startup without registering your intellectual property. Or entering a joint venture without a clear exit clause. These are the kinds of mistakes that preventive legal representation helps you avoid.

For Business Owners: Avoiding Legal Landmines

Entrepreneurs, listen up. Nigeria’s regulatory landscape is complex. From CAC filings to tax compliance, employment contracts to NDAs—having a lawyer on your team isn’t just smart, it’s strategic. Preventive legal counsel ensures your business is built on solid ground, not shifting sand.

For Everyday Nigerians: Peace of Mind

Even in personal matters—like drafting a will, negotiating a divorce, or resolving a landlord-tenant issue—early legal advice can make all the difference. It’s not about being paranoid; it’s about being prepared.

Prevention Is Cheaper Than Cure

Litigation is expensive. Court cases can drag for years. But a few hours with a lawyer to review a document or advise on a transaction? That’s an investment. Preventive legal representation is like insurance—you hope you never need it, but you’ll be glad you have it.

Find a Lawyer Today

Ready to take the smart step? Visit www.legalnaija.com to find verified Nigerian lawyers across various fields—from property law to corporate advisory, family law to tech law. Whether you need a quick consultation or long-term legal support, the right lawyer is just a click away.

Don’t wait for wahala. Get legal help now—and stay ahead of the game.

by Legalnaija | Oct 1, 2025 | Blawg

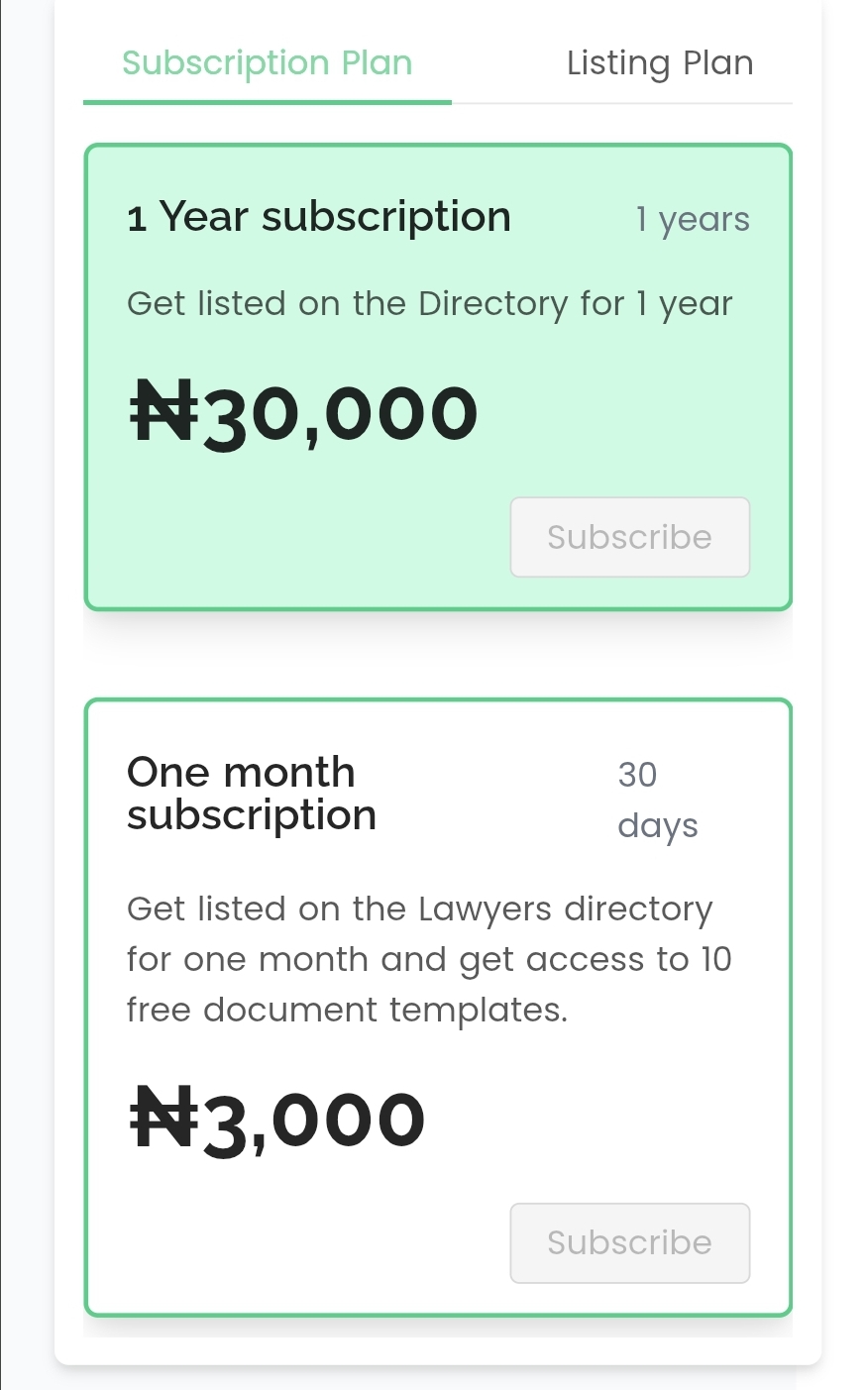

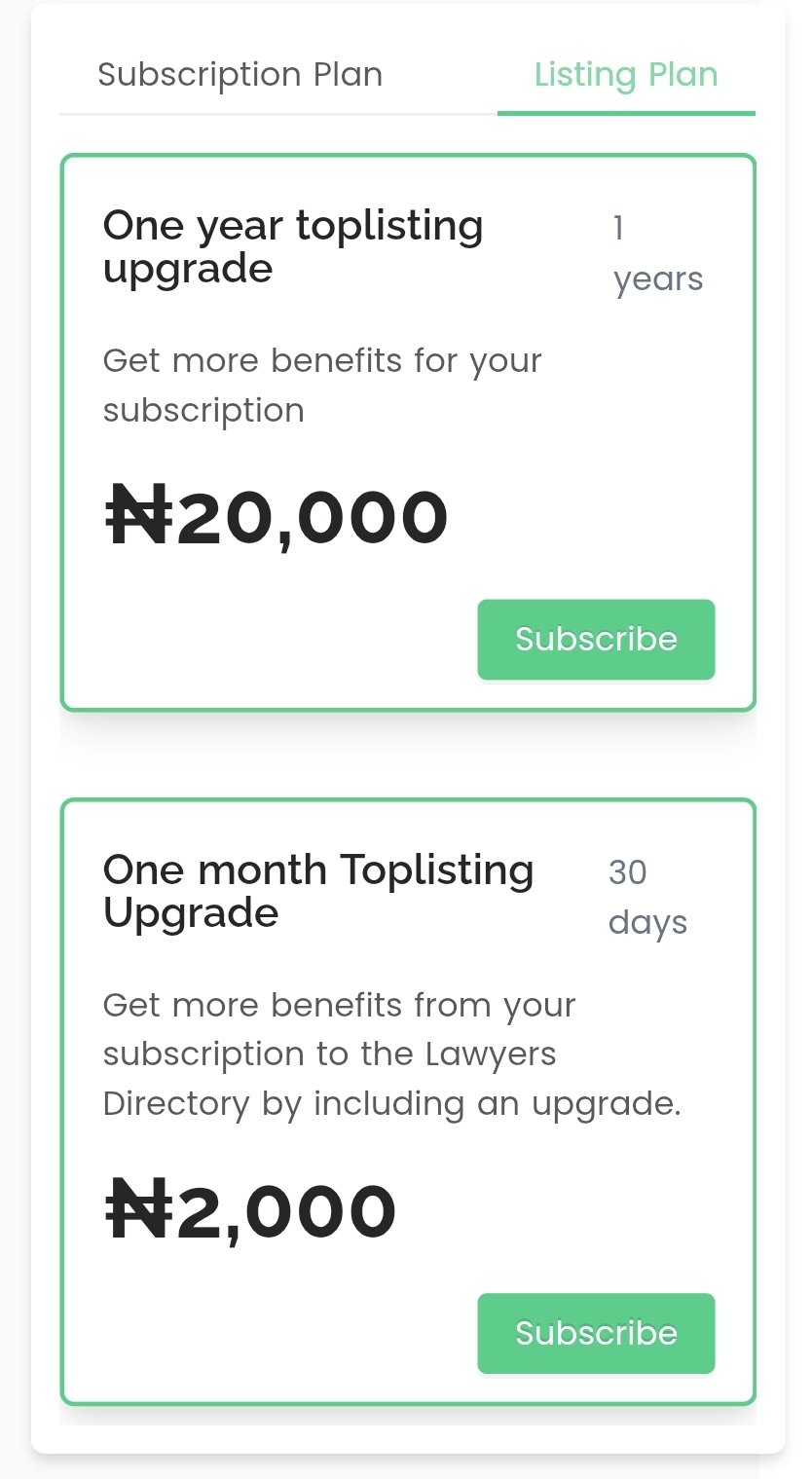

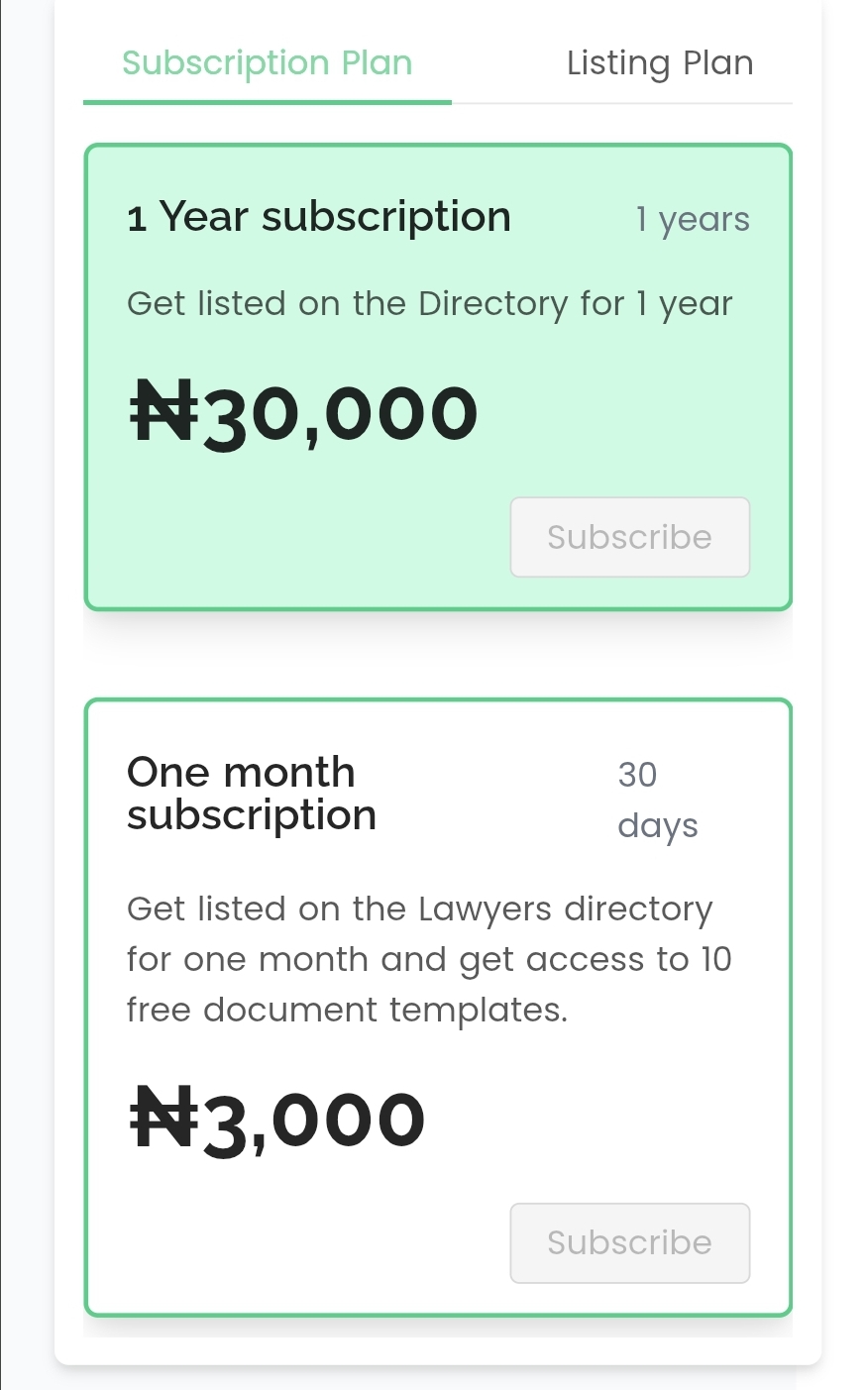

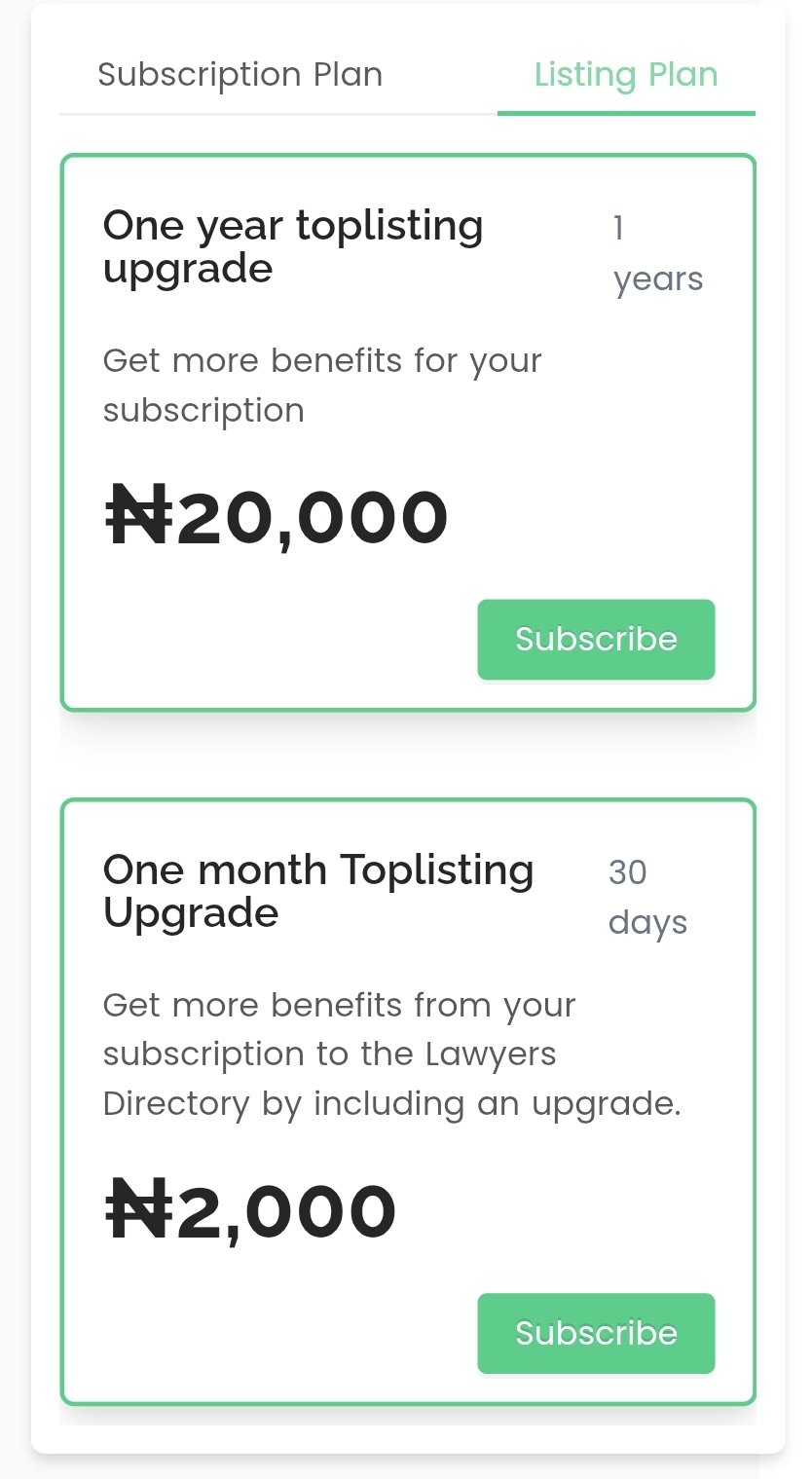

Lawyers, Don’t Let the RPC Hold You Back — We Can Advertise Your Practice For You!

The Rules of Professional Conduct (RPC) may restrict direct advertising by Nigerian lawyers, but that doesn’t mean your practice should remain invisible.

Legal directories like Legalnaija are fully compliant with the RPC — and they’re designed to help you shine. Being listed on the Legalnaija Directory isn’t just ethical, it’s strategic. It’s your gateway to visibility, credibility, and connection with clients who need your expertise.

Here’s the truth:

You don’t have to advertise — because we’ll do it for you. Legalnaija promotes your listing, showcases your practice areas, and helps potential clients find you, all within the bounds of professional ethics.

✅ Stay compliant

✅ Get discovered

✅ Grow your practice

Don’t feel limited. Feel empowered. Join the Legalnaija Directory today and let us help you stand out — the right way.

If you have a Legalnaija account, renew your subscription here – https://app.legalnaija.com/signin

If you are new to Legalnaija, sign up here – https://app.legalnaija.com/signup

For help or more information about registration or subscribing, kindly email hello@legalnaija.com or text 09029755663 on WhatsApp.

by Legalnaija | Sep 23, 2025 | Blawg, Training

Dr. Tolu Aderemi, Partner at the Firm Perchstone & Graeys and Chairman of the NBA Lagos 2025 Law Conference, has launched an Alternative Dispute Resolution and Emotional Intelligence training session for young lawyers. At a press briefing on 22nd September, 2025, Dr. Aderemi announced the training session in partnership with Mr. Fola Alade of FOTEFA Mediation Academy and the Business Law Academy.

Dr. Tolu Aderemi, in his introduction, highlighted how alternative dispute resolution, particularly arbitration has over the years become effective in resolving commercial disputes. Dr. Aderemi further explained that the upcoming Master Class will not only address ADR mechanisms but also emphasize dispute avoidance strategies. According to him, the one-year intensive training program, jointly driven by the Business Law Academy and Fotefa Mediation Academy, will cover ADR, Dispute Avoidance strategy and Emotional Intelligence, thereby producing more well-rounded practitioners.

Mr. Fola Alade of FOTEFA Mediation Academy also provided an overview of the program’s structure. He stated that it will run as a 12-week online course, designed to empower the next generation of dispute resolution practitioners. The program aims to equip lawyers, with a solid foundation in both the traditional pillars of ADR and sharpen the advocacy, analytical and interpersonal skills that define a competent ADR professional, while ensuring that participants are practice-ready for domestic and international engagements.

Mr. Alade outlined that the Master Class will begin with an orientation by Dr. Tolu Aderemi, followed by a negotiation module by Dr. Kolawole Mayomi, a mediation module to be led by Mr. Alade himself, and an arbitration module to be facilitated by Mr. Aaron Ogletree. Other facilitators will include Mrs Laura Alakija, Mr. Hamid Abdulkarim, and Mr. Rotimi Ogunyemi.

While the training session will have practical sessions, the program’s impact will be in threefold:

- For participants – producing confident, well-grounded ADR practitioners capable of stirring negotiation, mediation and Arbitration with professionalism and empathy.

- For the profession – strengthening Africa’s and Nigeria’s ADR ecosystem, decongesting the court dockets, and promoting a culture of peaceful dispute resolution.

- For society and businesses – fostering dispute avoidance and efficient dispute management, thereby improving the commercial environment.

Mrs. Fola, representing the Business Law Academy, while also addressing the audience explained that the program will open with an introduction to ADR, the history and global trends and feature carefully curated modules on ADR, dispute avoidance, and emotional intelligence. According to her, the course will blend theory with practical application, culminating in a closing ceremony that will showcase ADR simulations and celebrate participants’ growth. She concluded that the initiative will contribute to a more stable commercial environment, attract investment, and support sustainable economic growth.

During the interactive session, Mr. Austin Inyam asked about the advantages of ADR and whether non-lawyers could participate in the program. In response, Dr. Tolu Aderemi outlined the many advantages of ADR, including its speed, cost-effectiveness, and ability to preserve business relationships, while acknowledging that the traditional court system remains indispensable in the legal framework. He emphasized that, at best, both methods of dispute resolution should coexist. He further stressed that lawyers, as users of the Act, must understand not only the law but also the underlying principles of arbitration to prevent traits of litigation from finding their way into ADR practice. He concluded by noting that the Master Class is designed exclusively for legal practitioners.

Expanding on the subject, Dr. Alade described ADR as the “technology of dispute resolution,” likening its impact to that of technological innovation. He noted that ADR is universally recognized, enabling practitioners to operate across borders without the licensing barriers faced by litigators. He also observed that clients today are increasingly impatient and prefer their disputes to be resolved swiftly. As a result, they weigh the cost–benefit of pursuing a case in court for years even when they have strong claims, against the value of speedy justice, the likelihood of appeals, and the potential strain on business relationships. He noted that clients are also more inclined to seek lawyers with specialized expertise in the relevant area of dispute who can deliver effective and timely resolutions while preserving professional relationships with the opposing party.

Dr. Tolu Aderemi, in his closing remark, emphasized that the overarching objective of the Master Class is to develop well-rounded ADR experts. He assured participants that the faculty will focus not only on theoretical knowledge but also on practical application to ensure lasting impact.

Dr. Aderemi reiterated that this program, the first of its kind in Nigeria, will offer one of the highest levels of training on ADR combined with emotional intelligence. While the participation process will be rigorous to ensure quality, successful candidates will receive certificates at the end of the program. He also expressed appreciation to the Business Law Academy and Fotefa Mediation Academy for their partnership.

The mode of participation will be announced shortly and all lawyers are encouraged to participate fully in the training.

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

Why You Need a Lawyer Before Wahala Starts: The Power of Preventive Legal Representation

Why You Need a Lawyer Before Wahala Starts: The Power of Preventive Legal Representation