1.0 Introduction

Few technologies arrive

unannounced and few remain unchanged overtime. The development of techniques to

facilitate the fertilization of human eggs or ova is no exception. The medical

sector has not been let off the hook of the technological wave that has blown

across nearly all sectors of human lives. While IVF is now recognized as an

acceptable medical technique to combat the surging problems of infertility, it

is still being considered relatively novel.

It is pertinent to not that the innovation of IVF has not met with the

same response like other medical intervention like; vaccines and the like.

unannounced and few remain unchanged overtime. The development of techniques to

facilitate the fertilization of human eggs or ova is no exception. The medical

sector has not been let off the hook of the technological wave that has blown

across nearly all sectors of human lives. While IVF is now recognized as an

acceptable medical technique to combat the surging problems of infertility, it

is still being considered relatively novel.

It is pertinent to not that the innovation of IVF has not met with the

same response like other medical intervention like; vaccines and the like.

The new reproductive technologies constitute

a broad range of technologies aimed at facilitating, preventing, or otherwise

intervening in the process of reproduction.

In this piece of legal opinion the focus is on the legal and ethical

issues associated with in-vitro fertilization in Nigeria. On 25th July 1978, Louise

Joy Brown was born in Great Britain, being the first successful birth through

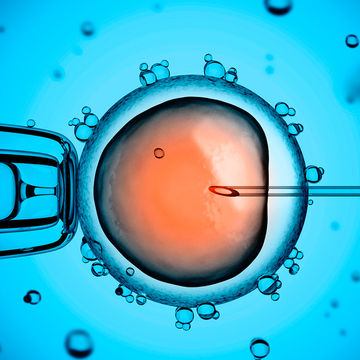

the use of in-vitro-fertilisation. The IVF in its simplest form involves the

hormonal monitoring and stimulation of the woman producing ova, harvesting the

ova, mixing same with sperm in a petri dish containing a culture medium. It

involves a three day waiting period (approximately) for embryo development,

before the embryo is transferred back to the woman. IVF has come to challenge

traditional views and positions on abortion. This has been occasioned by the

right to destroy embryo with the consent of the couple. It the United Kingdom

the traditional stand against abortion has been threatened by the freedom of a

partner to withdraw from the procedure at any time and ordered the fertilised

eggs or preserved spermatozoa to be destroyed.

a broad range of technologies aimed at facilitating, preventing, or otherwise

intervening in the process of reproduction.

In this piece of legal opinion the focus is on the legal and ethical

issues associated with in-vitro fertilization in Nigeria. On 25th July 1978, Louise

Joy Brown was born in Great Britain, being the first successful birth through

the use of in-vitro-fertilisation. The IVF in its simplest form involves the

hormonal monitoring and stimulation of the woman producing ova, harvesting the

ova, mixing same with sperm in a petri dish containing a culture medium. It

involves a three day waiting period (approximately) for embryo development,

before the embryo is transferred back to the woman. IVF has come to challenge

traditional views and positions on abortion. This has been occasioned by the

right to destroy embryo with the consent of the couple. It the United Kingdom

the traditional stand against abortion has been threatened by the freedom of a

partner to withdraw from the procedure at any time and ordered the fertilised

eggs or preserved spermatozoa to be destroyed.

2.0 Statement of the Problem

The filial relationship that results from an IVF procedure

is unprecedented and it comes with attendant problems which the legal framework

ought to cater for. Legal disputes may include the determination of who has

parental responsibility over a child begotten from IVF. The persons who have

the natural rights have become expanded from the usual two (mother and father)

to; the sperm donor, the egg donor, the surrogate womb mother, and the couple

who raises the child. IVF also raises questions of rights and liabilities as

they apply to the fetus, donors, and adoptive parents, as well as the role of

physicians and parenthood organisations, researchers, corporations, and government

in ensuring that the practice of IVF is not performed without adherence to

strict rules of ethical guidelines.

is unprecedented and it comes with attendant problems which the legal framework

ought to cater for. Legal disputes may include the determination of who has

parental responsibility over a child begotten from IVF. The persons who have

the natural rights have become expanded from the usual two (mother and father)

to; the sperm donor, the egg donor, the surrogate womb mother, and the couple

who raises the child. IVF also raises questions of rights and liabilities as

they apply to the fetus, donors, and adoptive parents, as well as the role of

physicians and parenthood organisations, researchers, corporations, and government

in ensuring that the practice of IVF is not performed without adherence to

strict rules of ethical guidelines.

According to Mccartan the role of the law in guiding

scientific development has not been clearly established, and in fact regulation

of scientific advancement has not been welcomed by those active in progressive

areas of medical research. She cites Burger, who opined that the law does

govern the advancements of medical science.

This article is necessary to bring to the fore the challenges inherent

in the practice of IVF and innovative roles the law can play to cushion the

adverse effect of such challenges.

scientific development has not been clearly established, and in fact regulation

of scientific advancement has not been welcomed by those active in progressive

areas of medical research. She cites Burger, who opined that the law does

govern the advancements of medical science.

This article is necessary to bring to the fore the challenges inherent

in the practice of IVF and innovative roles the law can play to cushion the

adverse effect of such challenges.

3.0 Legal/ Ethical Aspects of IVF

Practical concerns raised by IVF which have ethical and

legal implications are disposal of surplus embryos created in vitro that prove

unnecessary or unsuitable for a couple’s reproductive requirements,

implantation of several embryos that results in high, multiple pregnancy, and

creation of the same result by natural conception following medically induced

super ovulation, and the option of so called ‘selective reduction’ to reduce

multiple pregnancy. Multiple pregnancy involves health care of mothers,

foetuses in utero, and newborn children, possibly born prematurely with low

birth weight and risk of associated complications.

legal implications are disposal of surplus embryos created in vitro that prove

unnecessary or unsuitable for a couple’s reproductive requirements,

implantation of several embryos that results in high, multiple pregnancy, and

creation of the same result by natural conception following medically induced

super ovulation, and the option of so called ‘selective reduction’ to reduce

multiple pregnancy. Multiple pregnancy involves health care of mothers,

foetuses in utero, and newborn children, possibly born prematurely with low

birth weight and risk of associated complications.

Central legal issues in assisted reproduction are the

consent of both members of an infertile couple, consent of gamete or embryo

donor, and the legal status of a resulting child. A husband’s consent to his

wife’s insemination by donor is usually required, in order that any legal

presumption of his fatherhood be maintained. His objection would render the

child not his legal responsibility, and he may disclaim paternity if the wife

is serving as a surrogate mother to another man’s child. Sperm or ovum donors

must consent for lawful donation, but recovery of sperm from unconscious and

recently deceased men raises concerns such as how one can prove that his

consent was obtained in his unconscious state or before his death. Legal questions

that are also unresolved in many countries arise when donation of a couple’s

cyro-preserved embryo is possible, but only one member of the couple consents.

consent of both members of an infertile couple, consent of gamete or embryo

donor, and the legal status of a resulting child. A husband’s consent to his

wife’s insemination by donor is usually required, in order that any legal

presumption of his fatherhood be maintained. His objection would render the

child not his legal responsibility, and he may disclaim paternity if the wife

is serving as a surrogate mother to another man’s child. Sperm or ovum donors

must consent for lawful donation, but recovery of sperm from unconscious and

recently deceased men raises concerns such as how one can prove that his

consent was obtained in his unconscious state or before his death. Legal questions

that are also unresolved in many countries arise when donation of a couple’s

cyro-preserved embryo is possible, but only one member of the couple consents.

One of the consequences of assisted conception is the issue

of parental responsibility of a child begotten of IVF. This is adequately

demonstrated in the American case of the Calverts. Crispina and Mark Calvert

were unable to conceive a child due to the fact that Crispina had had

hysterectomy. Her ovaries, however, were intact and capable to produce valid

ova. Therefore, they drew up a contract with Anna Johnson who agreed to be a

surrogate mother and later relinquish the child to the Calverts. Calverts

agreed to compensate Johnson $10,000 in three installments part paid before and

part after the birth of the child. After successful in vitro fertilization and

transfer of the embryo to Johnson’s womb, Anna required full payment of the sum

threatening that otherwise she would keep the baby. Three successive courts

decided in favour of Calverts. The basis of the decision was different in

different courts: two courts relied directly on genetic relatedness of the

Calverts to the child and invoked the assumptions of other possible ways of

determination of parenthood. The third and final court based its decision

purely on the concept of ‘intent’ of the parties, that is, what was the intent

of them when they entered the contract?

of parental responsibility of a child begotten of IVF. This is adequately

demonstrated in the American case of the Calverts. Crispina and Mark Calvert

were unable to conceive a child due to the fact that Crispina had had

hysterectomy. Her ovaries, however, were intact and capable to produce valid

ova. Therefore, they drew up a contract with Anna Johnson who agreed to be a

surrogate mother and later relinquish the child to the Calverts. Calverts

agreed to compensate Johnson $10,000 in three installments part paid before and

part after the birth of the child. After successful in vitro fertilization and

transfer of the embryo to Johnson’s womb, Anna required full payment of the sum

threatening that otherwise she would keep the baby. Three successive courts

decided in favour of Calverts. The basis of the decision was different in

different courts: two courts relied directly on genetic relatedness of the

Calverts to the child and invoked the assumptions of other possible ways of

determination of parenthood. The third and final court based its decision

purely on the concept of ‘intent’ of the parties, that is, what was the intent

of them when they entered the contract?

The court case reveals two aspects of the impact of the new

reproductive technologies in defining kinship and gender. First, it

demonstrates that due to the new reproductive technologies, society is forced

to re-evaluate its assumptions about what is the basis of kinship and gender

relations. Second, they show that the ‘biogenetic’ basis, although perceived as

the basis, cannot be applied in the real situations. The procreative act,

marriage, donors of genetic material and the ones that engage in the nurturing

of the new creature (embryo and later the child) can all now be separated.

Prior to the new reproductive technologies, they all were supposed to be parts

of the same biologically grounded process. Since these roles can be delegated

now to different people, one cannot use the biological processes as the

determining factor to identify the kin persons. The intention of the court to

put more emphasis on the social seems to be logical since it still can identify

one person. While the biological facts have become confusing, the social ones

remain the same as before.`

reproductive technologies in defining kinship and gender. First, it

demonstrates that due to the new reproductive technologies, society is forced

to re-evaluate its assumptions about what is the basis of kinship and gender

relations. Second, they show that the ‘biogenetic’ basis, although perceived as

the basis, cannot be applied in the real situations. The procreative act,

marriage, donors of genetic material and the ones that engage in the nurturing

of the new creature (embryo and later the child) can all now be separated.

Prior to the new reproductive technologies, they all were supposed to be parts

of the same biologically grounded process. Since these roles can be delegated

now to different people, one cannot use the biological processes as the

determining factor to identify the kin persons. The intention of the court to

put more emphasis on the social seems to be logical since it still can identify

one person. While the biological facts have become confusing, the social ones

remain the same as before.`

The above attests to the fact that the implications of IVF

spans beyond legal implications to, medical, societal and psychological

implications

spans beyond legal implications to, medical, societal and psychological

implications

4.0 Evans v. United Kingdom: A Critique

The

facts

facts

Natalie Evans and her partner, Howard Johnston, began

treatment for Assisted Conception at clinic In Bath July 2000. Sadly, preliminary

tests revealed that Evans had serious precancerous tumors in both her ovaries;

as soon as some eggs has been harvested for the purposes of IVF, her ovaries

were to be remove. It was during the same hour-long consultation in October

2000 that Evans and Johnston were informed both of the existence of the tumors

and of the policy regarding consent to IVF. Eleven eggs were harvested and six

embryo’s created and placed in storage, in November 2000, Evans underwent an

operation to remove her ovaries. The plan was for the implantation to take

place once Evan’s health permitted, following a recommended minimum period of

two years. The alternative and less certain procedure of freezing unfertilized

eggs was not available at that clinic at the time. Unfortunately, in May 2002

the relationship between Evans and Johnston broke down. In July, Johnston wrote

to the clinic withdrawing his consent to implantation

treatment for Assisted Conception at clinic In Bath July 2000. Sadly, preliminary

tests revealed that Evans had serious precancerous tumors in both her ovaries;

as soon as some eggs has been harvested for the purposes of IVF, her ovaries

were to be remove. It was during the same hour-long consultation in October

2000 that Evans and Johnston were informed both of the existence of the tumors

and of the policy regarding consent to IVF. Eleven eggs were harvested and six

embryo’s created and placed in storage, in November 2000, Evans underwent an

operation to remove her ovaries. The plan was for the implantation to take

place once Evan’s health permitted, following a recommended minimum period of

two years. The alternative and less certain procedure of freezing unfertilized

eggs was not available at that clinic at the time. Unfortunately, in May 2002

the relationship between Evans and Johnston broke down. In July, Johnston wrote

to the clinic withdrawing his consent to implantation

In viewing the decision of the court through the lens of a

contract, with Natalie Evans as the offeror and Howard Johnston being the

offeree, there remains the question of appropriate remedy where the contract is

breached by one of the parties in this case Howard Johnston. The question that

is pertinent to ask is; whether the acceptance communicated by the offeree to

the offeror contributed to her decision to have her ovaries removed. While it

may be argued that the removal of her ovaries were inevitable, the acceptance

to be a part of the IVF procedure by her partner led her to carrying out the

procedure knowing it was her only chance to bear children. Granted that the

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 provides that either partner may

withdraw his or her consent in writing at any time before implantation in the

woman’s uterus. However, a marriage of the provisions of the Article 16 of the

United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and Article 23 of the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, would enable one to realize

that the right to marry, found a family and reproduce are inalienable rights.

It is not known to the writer at the time of writing this work whether there

exists a prototype of a pre-nuptial agreement for IVF procedures to protect

women like Natalie Evans. The object of the contract being the expected results

of the IVF procedure which would have seen that Natalie is not denied the right

to found a family.

contract, with Natalie Evans as the offeror and Howard Johnston being the

offeree, there remains the question of appropriate remedy where the contract is

breached by one of the parties in this case Howard Johnston. The question that

is pertinent to ask is; whether the acceptance communicated by the offeree to

the offeror contributed to her decision to have her ovaries removed. While it

may be argued that the removal of her ovaries were inevitable, the acceptance

to be a part of the IVF procedure by her partner led her to carrying out the

procedure knowing it was her only chance to bear children. Granted that the

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 provides that either partner may

withdraw his or her consent in writing at any time before implantation in the

woman’s uterus. However, a marriage of the provisions of the Article 16 of the

United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and Article 23 of the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, would enable one to realize

that the right to marry, found a family and reproduce are inalienable rights.

It is not known to the writer at the time of writing this work whether there

exists a prototype of a pre-nuptial agreement for IVF procedures to protect

women like Natalie Evans. The object of the contract being the expected results

of the IVF procedure which would have seen that Natalie is not denied the right

to found a family.

5.0 Conclusion/ Recommendations

The court’s decision in Evans V. United Kingdom rests the

deciding swing of the pendulum in the decision to withdraw consent. IVF comes

with a plethora of implications for inheritance laws, family law and adoption

law to mention but a few. The question remains as to what the response of the

law is in the face of these teeming challenges. It is largely unclear whether

there exists a demarcating line between one partner’s right to found a family

and the other partner’s right to withdraw from an IVF procedure. The law will

need to re-evaluate the traditional underpinnings of the ban on abortion.

Future research may examine with a view to charting a new course on the

modalities to be put in place for timeous regulation of IVF in Nigeria.

deciding swing of the pendulum in the decision to withdraw consent. IVF comes

with a plethora of implications for inheritance laws, family law and adoption

law to mention but a few. The question remains as to what the response of the

law is in the face of these teeming challenges. It is largely unclear whether

there exists a demarcating line between one partner’s right to found a family

and the other partner’s right to withdraw from an IVF procedure. The law will

need to re-evaluate the traditional underpinnings of the ban on abortion.

Future research may examine with a view to charting a new course on the

modalities to be put in place for timeous regulation of IVF in Nigeria.

REFFERENCES

1. R B

Bernholz and G N Herman, ‘Legal Implications of Human In Vitro Fertilization

for the Practicing Physician in North Carolina’ (1984) 6(1)Campbell Law

Review,p.44.

Bernholz and G N Herman, ‘Legal Implications of Human In Vitro Fertilization

for the Practicing Physician in North Carolina’ (1984) 6(1)Campbell Law

Review,p.44.

2. M K

McCartan, ‘A Survey of the Legal, Ethical, and Public Policy Considerations of

In Vitro Fertilization’ (2012)2(3) Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics &

Public Policy, p.696.

McCartan, ‘A Survey of the Legal, Ethical, and Public Policy Considerations of

In Vitro Fertilization’ (2012)2(3) Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics &

Public Policy, p.696.

3. W E

Burger, ‘Reflections on Law and Experimental Medicine’, (1968) 15 UCLA Law

Review, p. 436, 440

Burger, ‘Reflections on Law and Experimental Medicine’, (1968) 15 UCLA Law

Review, p. 436, 440

4. R J Cook.,

B.M. Dickens and M.H. Fathalla Reproductive

Health and Human Rights. (New York: Oxford University Press. (2003).

B.M. Dickens and M.H. Fathalla Reproductive

Health and Human Rights. (New York: Oxford University Press. (2003).

5. The

case of R. V. Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority, exp. Blood (1997) 2

All ER 687 (Court of Appeal, England).

case of R. V. Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority, exp. Blood (1997) 2

All ER 687 (Court of Appeal, England).

6. K

Sedlenieks, Klavs, ‘New Reproductive Technologies: Towards Assisted Gender

Relations.’ (1999) An Essay for MPhil Degree, Department of Social Anthropology,

University of Cambridge.

Sedlenieks, Klavs, ‘New Reproductive Technologies: Towards Assisted Gender

Relations.’ (1999) An Essay for MPhil Degree, Department of Social Anthropology,

University of Cambridge.

Akpan, Emaediong Ofonime is currently undergoing

postgraduate studies at the University of Uyo and majors in Consumer

Protection. She can be reached at akpanemaediongofonime@gmail.com

Photo Credit – www.fitpregnancy.com