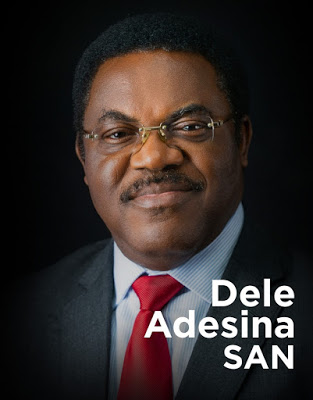

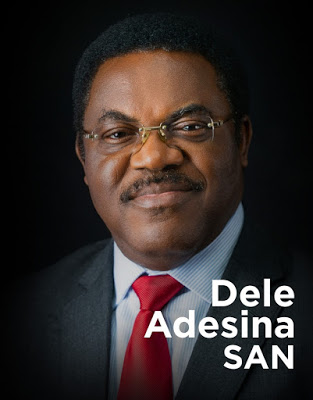

The Journey Towards Securing The Future Of The Bar Has Begun | Dele Adesina SAN

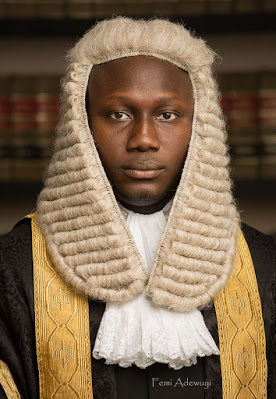

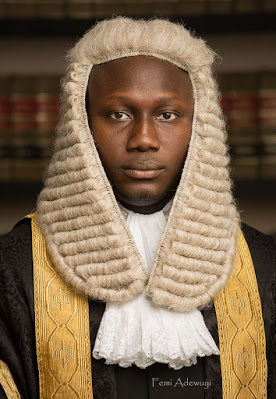

Our attention has been drawn to a Provisional List Of Candidates For NBA Elections 2020 believed to have been released by the ECNBA which did not include the name of our Dear Charles Ajiboye.

You will recall that our Dear Charles Ajiboye duly submitted his nomination forms for the Office of the *Assistant National Publicity Secretary* together with the required accompanying documents both electronically and physically through DHL.

Sadly, as at this time we are aware that NO information whatsoever has been received as to the omission of his name from the list.

It is our believe that it was slip error and that the ECNBA will correct same within the shortest possible time.

Please keep your faith alive, and hold your hopes up high. Charles Ajiboye is still in the race…don’t get it twisted.

Wisdom Ikhianosime,Esq.

For: Friends Of Charles Ajiboye

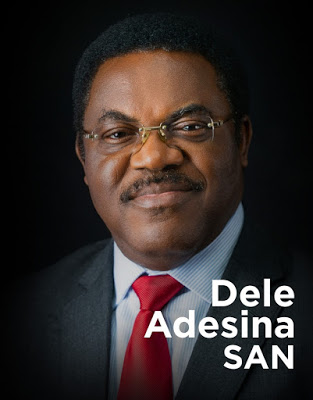

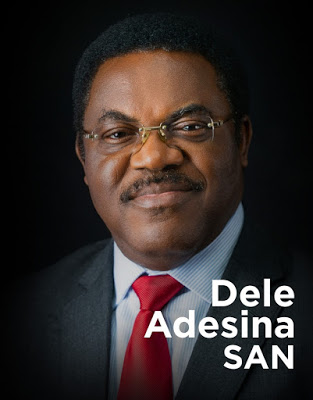

The News of the NBA partnering and signing a Contract with the Law-Pavilion Business Solutions Limited with the aim of providing Law-Pavilion Electronic Law Reports and Legal Research Software Licenses to Young Lawyers (that is, post-Call ages 1 to 7) who had paid their Bar Practicing Fees as at March 31 2020 was a commendable news. I congratulate the President of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), Mr. Paul Usoro SAN and members of his Executive for this initiative. Recognizing as I do that this is a very positive institutional welfare programme capable of enhancing the practice of Law by this strategic segment of members of our Profession.

This innovative idea is highly commendable as it presents an ample opportunity for Lawyers to fully embrace technology in their various practices. There is no doubt in my mind that this laudable provision of Law-Pavilion will ensure that they remain safe and able to work seamlessly from their respective homes and/or offices, while coping effortlessly with the seeming challenges presented by COVID-19 in a short run. On the long run, the innovation will enable young Lawyers to be more proficient in legal research, case analysis and review of legislations among other things and this would make them more beneficial to themselves, their principals, clients and the society at large.

Personally, it is my view that this laudable achievement is one which both you and your entire team must take pride in as initiators. It is an initiative worthy of support and continuity in our quest to provide institutional support for the young Members of our Profession. Good Lawyers are not the Lawyers who know the law but Lawyers who know where to find the Law. The initiative will no doubt produce good Lawyers that will secure the future of our Profession through knowledge, wisdom and good understanding of the workings of the Profession.

Once again, I thank you for this thoroughly thought-out initiative and other creative ideas including but not limited to the NBA Welfare Committee ably led by Dr. Wale Babalakin SAN for the benefit of the young members of the Bar.

DELE ADESINA SAN

June 12, 27 years ago was indeed a remarkable light at the end of a very dark tunnel. After years of dictatorial rule, it was time for democracy to play its part, but this as we all know was cruelly usurped by General Ibrahim Babaginda, or so it seems.

It would appear that democracy lost its mandate, power and influence to conquer cruel rule by the military government, but in actual fact, the June 12 saga showed us the plausibility of a one Nigeria coming together, irrespective of ethnicity, religion, and political ideology.

Power is the ability to make people act based on position; often leading to resentment, while influence is the ability to modify how a person develops, behaves, or thinks based on relationships and persuasion; often leading to respect. While the Babaginda junta relentlessly brandished their power in the face of Nigerians due to their political position, the influence of Moshood Abiola transcended though time thereby causing a revolution.

It was this dedicated show of influence by Moshood Abiola that brought unprecedented victory for him, even as he came on a Muslim-Muslim ticket. Nigeria embraced one another, they did away with their many divides that waged war on their unity for the sake of one Nigeria.

If influence is what led to unity, in June 12, then Nigerians; lawyers must learn that although power come from positions, it is the influence of a man /woman that truly makes the change.

The Nigerian Bar Association elections are near, it is important to sound the alarm that it won’t be position that makes the difference in the legal profession, it would be influence- the ability of our representatives, in whatever capacity, to listen, plan and influence the right policies to bring about a better legal profession, where all lawyers, young and old can be unitedly proud of.

Her husband is the NBA President, Mr. Paul Usoro.

June 12 is a very significant and historic day in the political history of Nigeria. Nigerians, on that day in 1993, showed the world the true meaning of unity in diversity, brotherhood across the borders, and togetherness when they jettisoned all primordial considerations be it religion, ethnicity, or tribe in electing their political leader in a very free, fair and transparent election. Regrettably, that historic feat was short-lived by the annulment of the said election. The fact of the annulment threw Nigerians back into Military dictatorship until 1999 when the present democratic dispensation began.

The significance of today made the present Administration to change Democracy Day in Nigeria from May 29 to June 12. It is therefore important to say *”Happy Democracy Day to all Nigerians including and in particular, my dear Colleagues of the Legal Profession”* especially as we prepare for the election of new leaders for our Association.

As we celebrate today, let us remember that our Constitutional Democracy is a work in progress. We still have a lot of steps to climb, problems to solve, and questions to answer. The beauty of today is that, June 12, can signify our political will and determination as a people to conquer our problems and challenges; some of which are real developments, low standard of living of the people, adherence to Rule of Law in all its ramifications including but not limited to the independence of the Judiciary and protection of Fundamental Rights and Civil Liberty of the people.

This is because democracy is essentially about the people and people are at the very centre of democracy. We must continually invest in the development of the people of our country and the Nigerian Bar Association has a role to play in advancing the progress of the people.

Happy Democracy Day.

Dele Adesina SAN, FCIArb

Let us never forget that government is ourselves and not an alien power over us. The ultimate rulers of our democracy are not a President and senators and congressmen and government officials, but the voters of this country.

Happy Democracy Day and God bless Nigeria 🇳🇬