by Legalnaija | Sep 29, 2020 | Uncategorized

INTRODUCTION

The right to life is sacrosanct to the bearer and

nobody has the authority to deprive them of this natural gift which the creator

has gifted them. Just as this right is intrinsic and fundamental, so is the

right to decide what happens to one’s state of health which ultimately has a

far-reaching effect on the person’s life.

This is the reason for obtaining the consent of a

patient before the conduct of any medical process or treatment on them is paramount.

Failure to do so will render the medical practitioner liable for breach of the

Medical Code and for assault on the patient or research subject. This work will

discuss the key concepts around Informed Consent, the components that

underlines this practice and the exceptional cases where it may be legally foregone.

AUTONOMY

Autonomy is a Latin word for

“self-rule”. Every human has an obligation to respect the autonomy of other persons, which

is to respect the decisions made by other people concerning their own lives.

This is in accordance with the fundamental right to human dignity. In medical practice, autonomy is usually expressed as

the right of competent adults to make informed decisions about their own medical care. The principle

underlies the requirement for a medical practitioner to seek the consent or

informed agreement of the patient before any investigation or treatment takes

place. The principle of patience autonomy mandates the health care providers to educate the patients about the treatment

options available to the patient; it prohibits the health care provider making the decision for the patient. It

is an absolute, inalienable right of the concerned patient.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent forms the basis of the

fiducial relationship existing between the patient and the health worker and it

is essential to the health worker’s ability to diagnose and treat patients as

well as the patient’s right to accept or reject clinical evaluation, treatment,

or both.

According to the provision of Part A section 19 of

the Code of Medical Ethics in Nigeria,

informed consent is:

“The permission granted in full

knowledge of the possible consequences, typically that which is given by a

patient to a doctor for treatment with knowledge of the possible risks and

benefits”.

Informed consent means that patients or

research subjects understand their health condition after much explanation by

their health care provider; the options available to them, and the attendant

benefits and risks of each option.

It

is important that the person undergoing the treatment has sufficient time to

weigh his or her option before making the decision. In fact, according to the code of medical

practice, the main purpose of

informed consent process is

to protect the patient.

A consent form

is a legal document that ensures an ongoing communication process between the

patient and health care provider. It enables the patient decide which treatment

they want to receive and whether

they even want it or not.

Additionally, informed consent allows the

patient to make decisions

with the close assistance of their healthcare provider. This collaborative

decision-making process is an ethical and legal obligation of healthcare

providers and a fundamental right of the patient.

Informed consent generally requires the patient or responsible party to

sign a statement confirming that they understand the risks and benefits of the

procedure or treatment and are willing to proceed and receive it.

The concept of Informed consent is not an

alien practice in Nigeria, its operation, as in other societies, is influenced

by relationships within the culture of the people and the ethos of the Medical

profession. It is modulated by extended

family relationships, the high level of religious expression,

the multiplicity of religions and ethnic groupings, and defined gender and age relationships

within the society. These influences, however, seem

vitiated in the educated patient.

Societies and cultures are neither homogenous

nor static. Therefore, variations in the practice of informed consent exist not

just in comparison with the Western world but also between and within

the different subcultures in the country.

The Nigerian medical community should improve

the ethical conduct of her healthcare workers through better education and

additional research on the consent needs of the Nigerian public.

ELEMENTS OF INFORMED CONSENT

The

key components of informed consent

are the ethical issues of research involving human subjects. The principles of autonomy, beneficence,

and justice are basic to these ethical issues and merit your consideration. Obtaining informed consent in medicine is a

process that should include:

·

Describing the proposed intervention to

the patient,

·

Emphasizing the patient’s role in

decision-making,

·

Discussing alternatives to the proposed

intervention,

·

Discussing the risks of the proposed

intervention

·

Making sure the

patient has the capacity (or ability) to make the decision.

·

The healthcare

worker must disclose information on the treatment, test, or procedure in

question,

·

The expected

benefits and risks, and the likelihood (or probability) that the benefits and

risks will occur must be fully explained.

·

The patient must

comprehend the relevant information.

·

The patient must

voluntarily grant consent, without coercion or duress.

BASIS

OF LIABLILIY

The basis of liability on the part of a

healthcare provider or researcher for not seeking the informed consent of the

patient or research subject is that; a person has the right to determine what

is done with his or her body. Failure to secure the consent in circumstances

not exempted by law, attracts liability on the part of the healthcare provider

or researcher. It is the informed consent

that distinguishes medical procedures from assault. Explaining the basis of

liability, JUSTICE CARDOZO stated in the landmark decision of Schloendorff v. Society of New

York Hospital, 105 N.E. 92 (N.Y. 1914)

that:

“Every

human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what

shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon who performs an operation without

his patient’s consent commits an assault, for which he is liable in damages.” (Underlined

is mine for emphasis).

It is important to note that informed consent

does not only apply to surgery. It applies to therapeutic and non-therapeutic

procedures, invasive and non-invasive treatment.

IMPORTANCE

OF INFORMED CONSENT

Consent to

treatment is among the most complex ethical issues healthcare workers face. Therefore,

it is important to understand what is involved.

No one can guarantee positive outcomes in

healthcare settings, but informed consent at least ensures that patients

understand the risks they undertake with treatment. It is also the law, when

patients agree to a treatment, they must sign paperwork indicating they

understand the risks and agreeing that doctors can take specific life-saving

measures if needed.

Informed consent creates trust between doctor

and patient by ensuring good understanding. It also reduces the risk for both

patient and doctor. With excellent communication about risks and options,

patients can make choices which are best for them and physicians face less risk

of legal action.

Informed consent allows patients to make their

own decisions, instead of the traditional approach where the doctor decides

what is best for them. This means medical professionals must offer enough

information to patients to enable them make a choice and provide enough time to

exercise this all too important right, where possible, so patients do not feel

pressured.

Pain medication and some medical conditions

can affect judgment and understanding, so doctors must consider these factors

when seeking consent from a patient.

EXCEPTIONS

TO INFORMED CONSENT

There are several exceptions to informed

consent acknowledged by the legal system in most countries.

The generally accepted exceptions to

the requirement for informed

consent include:

·

Emergencies.

In

an emergency, a doctor must act quickly to save lives. If stopping life-saving

efforts and describing the risks of a procedure will cause a delay that puts

the patient’s life further at risk, then the doctor does not need to obtain informed consent.

·

Voluntarily

waived consent

This is when the patient has voluntarily disclaimed

that he/ she needs not to be sought

before any treatment is carried out on him/her. In this case, the patient has

given the healthcare worker the sole responsibility to deal with his/ her

condition according to their best practice and knowledge. This must be reduced

to writing and signed by parties, to nip in the bud any chance of liability

that may arise, should the patient subsequently deny consent.

·

Where

the patient is incapacitated

If the patient’s ability to

make decisions is questioned or unclear, an evaluation by a psychiatrist to

determine competency may be requested.

A situation may arise

in which a patient cannot make decisions independently but

has not designated a decision-maker. In this instance, the hierarchy

of decision-makers, which is determined by each state’s laws, must be sought to

determine the next legal surrogate decision-maker. If this is unsuccessful, a

legal guardian may need to be appointed by the court.

·

Prior patient knowledge

The patient is already aware of the risks

involved in his or her treatment and has come to a conclusion which he/ she has

disclosed to the healthcare provider prior to the treatment.

·

Therapeutic privilege

This is when a patient can be expected to

become so emotionally distraught upon disclosure that he/she will not be able

to make a rational decision, and this may hinder his/her own treatment. It

acknowledges that in some situations the disclosure of certain risks would not

be in the patient’s best medical interest. This exception does not imply that

the health worker may withhold information simply because the patient will not

agree with the preferred treatment (and later claim it was for the patient’s

benefit). It should be exercised with great care and discretion and should not

be used as an excuse to withhold the truth, it is the patient’s entitlement.

·

Patients lacking capacity

Legally, capacity refers to a person’s

ability to understand the nature and quality of a transaction and to take

actions or make decisions that influence his/her life. A decision that a patient

lacks capacity is a significant one, as it strips them of their right to

control their life in relation to the decision in question.

Where patients lack capacity, other people

will have to make the decision for them. The health worker must consider the

views of anyone the patient asks the health worker to consult, or who has legal

authority to decide on their behalf or has been appointed to represent them.

Otherwise, the views of people close to the patient, who know the patient’s

preferences, feelings, beliefs, and values should be consulted to try to decide

whether the proposed treatment would be in the patient’s best interests. If the

patient regains capacity, they must be promptly informed what treatment has

been administered to them and why it was opted for.

CONCLUSION

A healthcare provider or researcher should

obtain the written, informed consent of the Patient or research subject;

failing which the healthcare provider or researcher will be liable. However,

the healthcare provide will escape liability if it comes under the exception

provided by law.

There are adequate laws regulating Informed

Consent in Nigeria. The problem is with the compliance. The mechanism to ensure

compliance can be improved. Two great factors affecting the issue of informed

consent are; awareness and finance. On one hand, most people are not aware that

their healthcare providers are obligated to get their consents before carrying

out treatment or medical examination. On the other hand, they are also ignorant

of the fact that they are entitled to redress. Some healthcare providers are

also ignorant of the law on informed consent. Those who are aware of the

necessity for informed consent, do not seek redress because of the cost.

Written by:

MUSTAPHA MOYOSORE. is with Messrs O. M. Atoyebi, SAN & Partners

(OMAPLEX LAW FIRM) where she works in the Corporate and Commercial Department

of the Firm. She has an in-depth understanding of Medical Law and Minin Sector

and has worked with various key industry stakeholders and facilitated several

transactions.

by Legalnaija | Sep 22, 2020 | Uncategorized

This training will span over the course of three weeks and will cover Power; Public Infrastructure (PPPs & Concession Arrangements); and the Oil & Gas Sectors. The faculty and speakers are seasoned professionals who will draw on their expertise in dispute resolution, project management and claims management across these three sectors.

This training is most beneficial for experts in the Power & Energy Sector, Oil & Gas Sector, Infrastructure Concession Arrangements PPPs and of course Legal Practitioners.

The workshop is a collaborative effort between LACIAC and Association for Consulting Engineering in Nigeria, with the support of @Hogan Lovells, @Bentsi-Enchill Letsa & Ankomah, @Linklaters, @Aluko & Oyebode, @Baker McKenzie and @Funmi Roberts and Co.

Training Module:

•Construction Projects in the Power Sector (6-7 October 2020)

•Construction of Public Infrastructure (including PPPs & Concession Arrangements)13-14 October 2020

•Construction Projects in the Oil & Gas Sector(19 & 21 October 2020)

For registration, please click here: https://www.laciac.org/dimap/

For more details, please see the brochure here: https://www.laciac.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/DiMAP.pdf

by Legalnaija | Sep 20, 2020 | Uncategorized

Hi,

One huge issue in the world today is that people are not

familiar with their rights and because of this they get taken

advantage of by security agencies, business partners or even fellow citizens

who appear to be more powerful and better connections.

It is extremely important to know your legal and

Constitutional rights. These rights are the

foundation of our legal system and are in place for the

protection of every citizen of this country. Failure to know and utilize these

rights leads to their erosion and possibly to you getting yourself deeper

into trouble.

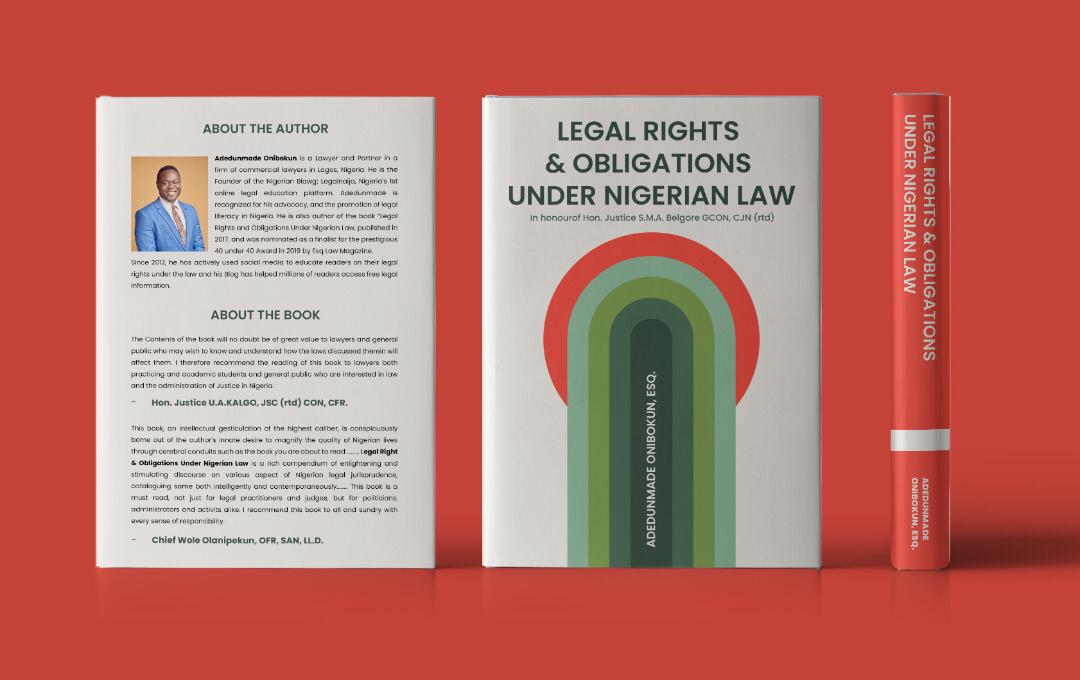

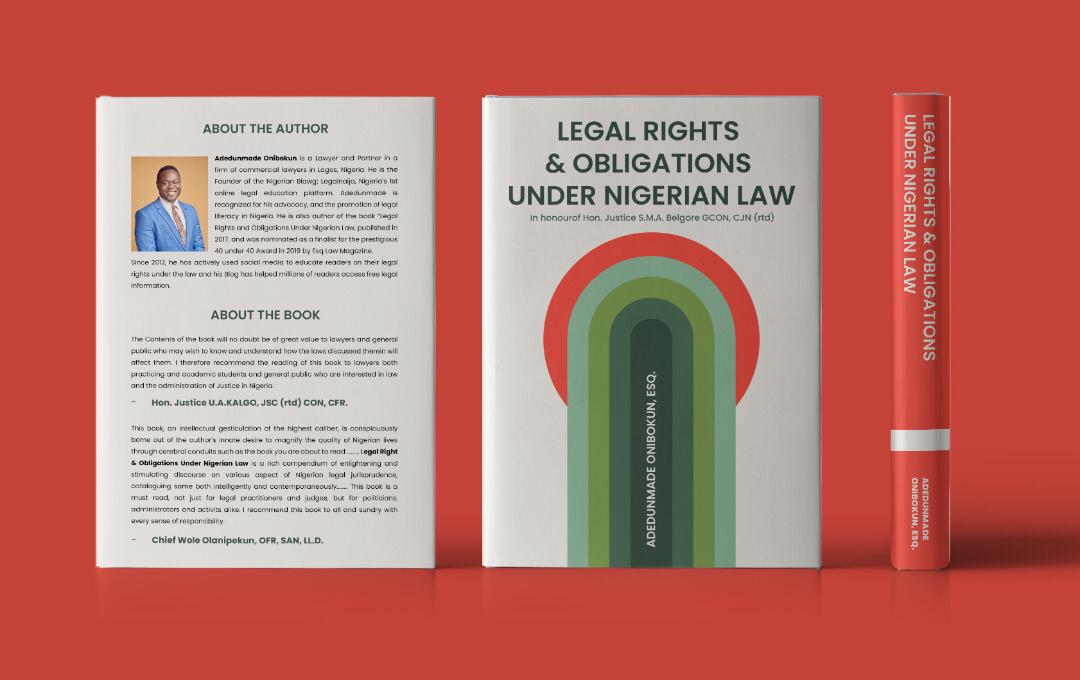

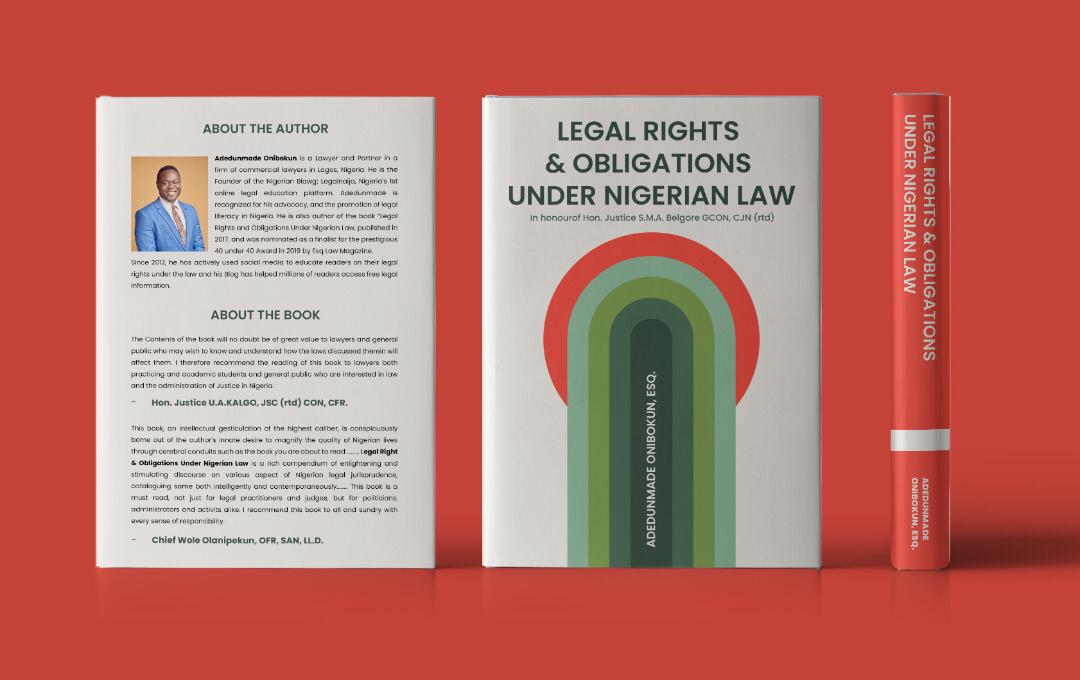

Kindly allow me introduce you to a tool to help you learn

your legal rights and stay updated. The LEGAL RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS UNDER

NIGERIAN LAW Ebook contains layman explanations for over 80 topics of law

including different areas such as Family Law, Divorce, Business Law, Tenancy

and Property Law to mention a few.

You can order your copy for here for N3,000 only.

Remember ignorance of the law is not an excuse. Purchase your Ebook Now.

by Legalnaija | Sep 19, 2020 | Uncategorized

ABSTRACT

Couple of days ago, I was requested to furnish

legal opinion on a judgement SUIT NO. NICN/LA/160/2017 delivered in June, 2020

by National Industrial Court of Nigeria. In the said judgement, the honourable

trial court, in its respectful wisdom, held that statute of limitation is not

applicable to contract of employment. The nucleus of the judgement was the

court’s heavy reliance on N.R.M.A. & FC vs Johnson (2019) 2 NWLR (P 1656)

SC 247. This piece of writing considers the applicable authorities and

maintains that statute of limitation is applicable to contract of

employment.

1. BACKGROUND

The precis of the judgement under examination is

that, the claimants were dismissed from the employment of the defendant in 2009

-the claimants were natural persons while the defendant was a corporate person.

The claimants instituted an action at National Industrial Court in 2010,

challenging their dismissal. The judgment of the court was delivered in 2016 in

the claimants’ favour. The claimants, yet again, in 2017, approached the same

National Industrial Court, claiming for their employment entitlements via

another fresh suit. The defendant raised, among others, the defence of statute

of limitation. Though finding that the cause of action accrued in 2009, the court

assumed jurisdiction and held that the matter was not statute barred. Relying

on the judgement of the Supreme Court in N.R.M.A. & FC vs Johnson (2019) 2

NWLR (P 1656) SC 247, the Trial court held:

“I have seen the arguments of counsel and without

need to rehash, I find that the position of the law regarding the applicability

of statutes of limitation on employment contracts has been clarified by the

Supreme Court in the case of N.R.M.A. & FC vs Johnson (2019) 2 NWLR (Pt

1656) SC 247 where His Lordship Ariwoola, JSC declared that statutes of

limitation do not apply to employment/service contracts. As the reliefs for the

claimants’ gratuity in this case relate to claims that inured as a result of

contracts of service with the defendant, this court is bound to follow these

decisions of the Appellate courts. I therefore find that this action is not

caught by Limitation law of Lagos State. I so hold.”

The twain questions this paper seeks to answer

are: 1. Was the case of N.R.M.A. & FC vs Johnson (2019) 2 NWLR (P 1656) SC

247 applicable in this case? 2. Does contract of employment now enjoy

perpetuity going by the reasoning of the trial court?

2. EXAMINATION

OF N.R.M.A. & FC vs JOHNSON (2019) 2 NWLR (P 1656) SC 247

Johnson and others were employed by National

Revenue Mobilization Allocation and Fiscal Commission (N.R.M.A. & F.C.) The

Commission later terminated their employment. Johnson and his co-employees sued

the Commission for wrongful dismissal and claimed their salaries and other work

benefits. The Commission raised the defence that, it, the Commission, was a

Federal Government agency and no legal action could be commenced against the

Commission except within three months of accrual of the cause of action as

provided by section 2, Public Officers (Protection) Act. The relevant provision

of the Public Officers Protection Act Cap 379, Laws of Federation of Nigeria

1990 relied upon by the Appellant in Section 2 (a) states:

“Where any action, prosecution or other

proceeding is commenced against any person for any act done in pursuance or

execution of any act or law or of any public duty or authority, or in respect

of any alleged neglect or default in the execution of any such act, law, duty

or authority, the following provisions shall have effect – (a) The action,

prosecution or proceeding shall not lie or be instituted unless it is commenced

within three months next after the act, neglect or default complained of, or in

case of a continuance of damages or injury within three months next after

ceasing thereof.”

The Supreme Court, discountenancing this

argument, held:

“In this matter, while the appellants maintain

that the action is caught by section 2a of the Public officers Protection Act,

the respondents argue that the act is inapplicable. There is no doubt, a

careful reading of the respondents’ claim will show clearly that it is on

contract of service. It is now settled law, that section 2 of the Public

officers Protection Act does not apply to cases of contract.”

This same position of the law has been variously

recognised and echoed by our courts for quite a long period of time before

2019. The Court of Appeal’s decision in NIGERIAN ARMY v. ABAYOMI (2019)

LPELR-47084(CA) buttresses this position when it held, on when the Public

Officers Protection Act will apply:

“Two conditions must coexist before a person can

avail himself of the protection and these are (i) the person must be a public

officer; and (ii) the act done by the person in respect of which the action was

commenced was an act done in pursuance or execution or intended execution of a

law or public duty or authority – Central Bank of Nigeria Vs Okojie (2004) 10

NWLR (Pt 882) 488, Hassan Vs Aliyu (2010) 17 NWR (Pt 1223) 547. Where either of

these conditions is missing, the person concerned does not come under the

provisions of Section 2 of the Public Officers Protection Act and an action

against him is not caught by the three months limitation period.” Per

ABIRU, J.C.A. (Pp. 30-34, Paras. D-B).”

The Johnson’s case in question only excluded

application of three months limitation of action contained in Public Officers

Protection Act and analogous enactments, in contract of employment or where the

defendant government agency does not act in discharge of its duty. The case is

not a precedent on employment contract of six/five-years limitation contained

in various Limitation Act/Law.

3. DISSIMILITUDE

BETWEEN THE TWO CASES

In the Johnson’s case, the party invoking statute

of limitation under Public Officers (Protection) Act was a Federal Government

Agency and the Supreme Court refused to be swayed. Conversely, in the instant

case, the party raising the defence of statute of limitation is not a federal

government agency and did not invoke the provision of Public Officers

(Protection) Act or Law, rather, it invoked the statute of general limitation

i.e. Limitation Law, which is the only limitation law applicable in this case.

For the sake of emphasis and at the risk of

repetition, the position taken by the Supreme Court in Johnson has been

enjoying full compliance of subordinate courts but not in the manner and

instance in which the trial court applied it. The Court of Appeal held in FUTO

v. AMCON & ORS (2019) LPELR-47327(CA):

“On the contention that the 3rd party notice

is against a public officer which is the Appellant, this issue has long been

settled by the Apex Court in a long line of cases that the statute of

limitation does not apply to contract, it is the subject matter that determines

if the public officer is to benefit from the application. It is granted that

the Appellant is established by statute and enjoys the protection of the Public

Officers Act but having admitted that the subject matter is simple contract

therefore it does not apply to it.”

As indicated above, the case of N.R.M.A. & FC

vs Johnson (2019) 2 NWLR (P 1656) SC 247, and similar precedents largely relied

on by the trial court, were based on a special provision of limitation in

special circumstances against public officers or offices.

4. STATUTE

OF LIMITATION REMAINS APPLICABLE TO CONTRACT OF EMPLOYMENT

The general position of the law is that, a suit

initiated outside the prescribed period of time is statute barred and the

potential claimant is deemed to have been slumbering till time lapses and he is

left with no legal remedy in a court of law. Limitations to actions are

basically provided by statutes, though being a form of procedural law. In

Nigeria jurisprudence, there are specific statutes which stipulate time within

which legal action could be instituted against some bodies and in some special

circumstances. Examples of such special provisions are found in statutes such

as Electoral Act, Public Officers Protection Act, Nigerian National Petroleum

Corporation Act or similar Acts/Laws establishing government institutions.

There is also a general statute of limitation titled “Limitation Act/Law”,

which evenly applies to all persons and in all instances.

The scope of applicability of limitation act/law

is to all and general matters of any nature except and save the one excluded by

another parallel statute. In giving nod to this, the court held in CBN v.

HARRIS & ORS (2017) LPELR-43538(CA)

” Now, it is trite that where a statute

prescribes that an action must be filed in Court within a specific period, such

provisions of the law must be strictly complied with, in order to avoid being

caught up by the limitation under the law. In OBA J. A. AREMO II v. S. F.

ADEKANYE & ORS (2004) 19 NWLR (pt. 891) 572; (2004) LPELR – 544 (SC), the

Supreme Court, per EDOZIE, JSC held at 17, paras C – F, thus: “Where a

statute of limitation prescribes period within which an action must be

commenced, legal proceedings cannot be properly or validly instituted after the

expiration of the prescribed period. When an action is statute-barred, a

plaintiff who might otherwise have had a cause of action loses the right to

enforce it by Judicial process because the period of the time laid down by the

limitation for instituting such an action has elapsed….” Per

OBASEKI-ADEJUMO, J.C.A. (Pp. 16-17, Paras. D-D)”

A case on all fours with the case decided by the

court in the judgement under appraisal is TRANSOCEAN SUPPORT SERVICES (NIG) LTD

v. MINA PRAH (2019) LPELR-47249(CA) in which contract of employment of a

claimant was held to be caught by limitation period:

“It is not in doubt that the action was

commenced on 30/11/2000 when the writ of summons was filed. The Limitation Law

of Rivers State Cap 80 Laws of Rivers State 1999, provides in Section 16

thereof that; No action founded on contract, tort or any other action not

specifically provided for in Parts I and II of this law shall be brought after

the expiration of five years from the date on which the cause of action

accrued. From the above provision, it can be seen that the limitation period in

actions founded on contract is five years”.

The holding quoted above remains the true

position of the law; contract of employment is still under the reach of the

long hand of limitation law, to hold otherwise would be giving it an eternal life

which would be inequitable to the adverse party.

5. APPLICATION

OF JUDICIAL PRECEDENT

There is no gainsaying that a trial/subordinate

court is inescapably duty bound to follow decision of a superior court. The

prerequisite for the application of such stare decisis is that there must be

substantial similarity between the case decided by the superior court and the

one present before a subordinate court; similar facts and similar legal

principles, as held in INTEGRATED REALTY LTD V. ODOFIN & ORS (2017) LPELR

48358(SC):

“The application of the principles of stare

decisis or judicial precedent does not involve an exercise of judicial

discretion. It is what must be done; mandatory. The doctrine is based on the

relevant likeness of or between the cases if there is no likeness between the

two, it is an idle exercise to consider whether the previous one should be

followed or departed from. It is settled law that a previous decision is not to

be departed from or even followed, where the facts or the law applicable in the

previous case are distinguishable from those in the latter case.”

Also, in LAWAL v. MAGAJI & ORS (2009)

LPELR-4427(CA), it was held:

“For a previous decision to serve as an

authority in any given case, it must be contextually situated to the facts, law

and rules in the case under consideration. Previous decisions do not apply

generally across board unless the facts are the same or sufficiently similar

and the law/rule applied in the previous case can be said to be in pari materia

with that applicable to the case under consideration.” PER SANKEY, J.C.A. (P.

50, paras. C-E)”

It is settled law that where the facts of a case,

the principle of law stated by Superior Court (Supreme Court in this instance),

is not with exact similitude with the case before a subordinate court, the

subordinate court is not duty bound to apply that principle of law.

6. CONCLUSION

The right to enforce an action on contract of

employment is not a perpetual right but a right generally limited by statute.

Public Officers Protection Law and similar statutes of limitation do not apply

to contracts which a public authority makes but which is not in the discharge

or performance of its statutory duty. However, the protection applies to

contracts or actions which the public authority has a duty under a statute to

make. The application of judicial precedent is inevitable in the predictability

of matter’s outcome as it finetunes our judicial system and makes sensible the

hierarchy of courts. This application is however founded on binary pillars:

substantial similarity of fact and of legal principle.

Author:

Hafeez Folohunsho Zubair is a dynamic lawyer who

practises in Lagos, Victoria Garden City (V.G.C.), Lekki, and can be reached

on: +2347038816822, hafeez4a@gmail.com

by Legalnaija | Sep 17, 2020 | Uncategorized

When a person publishes false statements which seek to defame another’s character, it is referred to as libel. For an action for libel to be successful, one of the grounds is that such writing must have been published.

A true statement on the contrary, can never be defamatory as the written publication must be false and without lawful justification for it to be defamatory.

In such situations anyone who is a victim of libel can sue for damages at the appropriate court. Its however important to note that an action for libel cannot be brought after 6 years from the date of which the action occurred.

Do you have any questions on defamatory statements, post a comment or send us a DM

#nigerianlawyers #aoclegal #defamation #libel #barrister #slander

by Legalnaija | Sep 16, 2020 | Uncategorized

INTRODUCTION

The Nigerian Local Content Development and

Enforcement Commission Bill, 2020, (the “Bill”) is seeking to repeal the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content Act,

2010 (hereinafter referred to as the “Act”). This shortsighted initiative

emerged out of the misconstrued perception of the true purpose behind the

issuance of the Executive Order 03 signed

by the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria seemingly in support of

Local Content, which mandates all Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs)

to grant preference to local manufacturers of goods and service providers in

their procurement of goods and services.

Also, another misconception is the

proclamation entitled “Presidential Executive Order for Planning and Execution

of Projects, Promotion of Nigerian Content in Contracts and Science,

Engineering and Technology,’’ by President Muhammadu Buhari, pursuant to the

authority vested in him by the Constitution, which was signed on Friday,

February 2, 2018, the Executive Order

No. 5 (“EO5”) by which all Ministries, Departments and Agencies (“MDAs”) of

Government were directed to engage indigenous professionals in the planning,

design and execution of National Security projects and maximize in-country

capacity in all contracts and transactions with science, engineering and

technology components.

These are directives

which can be easily actualized through the simple release of Guidelines or

modalities to that effect by the concerned MDAs without the need to enact a new

Local Content Law, let alone repeal the existing Act.

While this move

introduced by the Bill could be considered as remotely development-driven on

the surface, however, its bid to repeal the hitherto existing NOGICD Act, by

establishing a Local Content Commission and expanding the scope of Local

Content into all other Sectors of the economy, will only result in the

furtherance of unwarranted bureaucratic bottlenecks, which will hamper the much

desired rapid growth of the economy if assented to. This work exposes the

attendant shortfalls of the Bill, along with the impracticability of the

innovations it seeks to import into the economic structure of the country and

expound on why efforts should rather be channeled along the lane of properly

revamping the NOGICD Act already before the House of Representative and

undergoing some salient modifications, rather than obliterating it completely.

THE EXCLUSIVITY OF LOCAL CONTENT LAW TO THE OIL AND GAS

SECTOR

Local content

requirements are provisions (usually under a specific law or regulation) that

commit Foreign Investors and companies to a minimum threshold of goods and

services that must be purchased or procured locally. From a trade perspective,

local content requirements essentially act as import quotas on specific goods

and services, where Governments seek to create market demand via legislative

action. It ensures that within strategic Sectors particularly those such as Oil and Gas with large economic rents,

or vehicles where the industry structure involves numerous supplier’s domestic

goods and services are drawn into the industry, providing an opportunity for

Local Content to substitute domestic value-addition for imported inputs.

The rationale for

Local Content requirements is especially strong, particularly for the Energy

Sector. Apart from the United Kingdom, very few new energy producers including

Norway, long considered as the gold standard Local Content had, upon discovery

of their Oil and Gas deposits, stated the requisite industrial capacity to

serve as an internationally competitive platform for exploration, extraction,

distribution and export. Given that the Nigerian Oil and Gas industry is nearly

a century old, the dominance of established operators and the sophistication of

energy technology particularly for offshore deposits implies that emerging

energy producers will, at the outset, nearly always depend on foreign firms.

While energy sector investments (if properly managed) can ensure a steady revenue

stream and constant (and in the case of developing countries, rising) demand

levels, its exploitation however, requires sophisticated and cutting-edge

technology, a ready-made demand for a wide network of suppliers in virtually

all areas of manufacturing and services, and ongoing employment for trained

staff, both at home and in other energy-producing countries around the world.

Therefore, the reason

for having a Local Content Development Act specifically enacted for the Oil and

Gas Industry was not just to create more jobs but primarily to ensure

technology transfer of the grossly technical expertise applied in the Oil and

Gas Industry among other industry-based objectives. Countries all over the

world reserve Local Content laws for exploration of natural resources

especially in relation to the energy sector and this is because they desire to

build the necessary capacity to cater for that sector without high dependence

on external bodies.

Similarly, a cursory

look at the regime of Local Content in other Countries such as Ghana, will

reveal that the whole concept of Local Content not only resides with the Oil

and Gas sector, but also focuses on production and utilization of the Country’s

resources, and this puts away the need to have it present in other sectors.

Regulation 49 of its Petroleum (Local Content and Local Participation)

Regulations, 2013 L.I 2204, defines Local Content thus:

“The quantum or

percentage of locally produced materials, personnel, financing, good and

services rendered in the petroleum industry value chain and which

can be measured in monetary terms” (Underlined is ours for emphasis).

Having so defined

local content, the country has no other law on the area, as this will mean an

overstretching of its objectives.

Similarly, Section

106 0f the NOGICD Act defined “Nigerian Content” as thus:

“The quantum of composite value added to or created in the Nigerian

economy by a systematic development of capacity and capabilities through the

deliberate utilization of Nigerian human, material resources and services

in the Nigerian Oil and Gas industry” (Underlined is ours for emphasis).

THE BILL LACKS A CLEAR-CUT APPLICATION AND DIRECTION

Unlike the NOGICD Act

which provides for a clearly-worded spectrum of its application as regulating

activities in the Oil and Gas Sector, and thus makes for ease of its

enforcement, the Bill in question seeking to repeal the Act has failed to

delimit itself to any relevant Sector(s) of the economy or even spell out the

nature of the exact activities it intends to regulate. It equally does not

provide for the purpose its eventual enactment will achieve, which is in sharp

contrast with the NOGICD Act, the focal point of which is the implementation

and monitoring of Nigerian Content, ensure and encourage the full indigenous

participation and transfer of technology to Nigerians and the provision for the

development of Nigerian Content in the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry, as

vividly indicated by the wordings of the sections that ran through its pages

and even more so, in the clauses of the Bill (NOGICD Act (Amendment) Bill)

seeking to amend it.

The Local Content

Development and Enforcement Commission Bill on the other hand is not Sector

specific and other Sectors of the Nigerian economy comprises of Services,

Mining, Forestry, Agriculture, Transport, Tourism, Energy, etc. Considering

these Sectors are made up of 70% low income earners and striving entrepreneurs,

it is quite an enormous task if not an outright impossibility to implement the

wordings of the Bill. This deficiency it has by itself brought to the fore in

many of its proposed clauses. Prominent among which is the very first Clause

that hinges on the number of objectives it undertakes to achieve. Some

provisions are stated below:

Clause 1

The objectives of

this Bill include —

“(1) The imposition

of the application of Nigerian Local Content to any transaction in which public

fund belonging to the Federal Government of Nigeria or any of its arms and/or

agencies is used in any sector of the Nigerian economy, in donor or loan funded

projects and in activities carried out by any entity in possession of an

investment agreement with any arm of the Federal Government of Nigeria or any

of its agencies;

(2) The imposition of

Nigerian Local Content to transactions in all sectors of the Nigerian economy

where regulated activities are carried out especially in the petroleum, solid

minerals mining, construction, power, information and communication technology,

manufacturing and health sectors of the Nigerian economy;”

The foregoing provisions alone without

addition, are an obvious pointer to the fact that the Bill is certainly biting

a lot more than it can chew. Given that an innumerable percentage of publicly

funded transactions involving the Federal Government, its Arms, Agencies in

various sectors and activities by entities in investment Agreement with these

bodies, are conducted year in and year out, of which an accurate data and

status reports of are unfortunately not obtainable in any of the regulatory or

statutory establishments empowered to oversee and monitor these transactions.

If such primary

duties have been so neglected over the years, it automatically follows that

there is absolutely no footing upon which the imposition of the application of

Local Content can possibly thrive, as multiple projects and activities have not

been and are still not being tracked, thus, breeding more avenue for; perpetual looting of funds, low or zero

revenue generation and abandoned or uncompleted public works, the sum of which

could have been positively harnessed towards achieving the fast growth of the

economy and according more impetus to public-private-partnership which will aid

the smooth implementation of government policies, bring about robust economic

and commercial boost and add to the volume of the national wealth.

Conversely, the NOGICD Act has maintained a

solid record since its inception 10years ago, as it has remained focused on

achieving its sole objective, made possible by the specific nature of its

application to the Oil and Gas Sector, the mainstay of the economy and large

contributor to the overall national GDP. Interestingly, about $9 billion has

been retained from the average $20 billion being spent in the Oil and Gas

industry yearly due to the implementation of the Act and about Nine Million

man-hours has been achieving in training, with indigenous players owning about

40% of marine vessels operating in the industry. These are only a few of the

laudable economic transformations ushered in by the Act as a result of the

clarity and narrowed application of its mandates and the powers, functions and

roles exercised by the agency saddled with the onus of giving effect to its

sector-based provisions, the Nigerian Content Development and Monitoring Board.

ADDITIONAL EXPENSES TO THE NATIONAL BUDGET

It is beyond debate

that an Act to make provision for Local Content on all sectors of the economy

would not only be too voluminous and incapable of capturing all necessary

developments it ought to, but it will equally increase the amount of expenses

accruing to the annual national budget in running the costs of the numerous

Directorates and Departments the Bill seeks to establish and in setting up

offices for more Directors. This is especially

because the new Departments are more of a duplicate to the already existing

Departments in the Ministries. Instead of creating new Directorates and

Departments, it is advisable that the provisions in this Bill be used as an

upgrade to the already existing Departments to properly discharge their

administrative functions.

CONCLUSION

Before

the advent of the Bill, the NOGICD Act has withstood the test of time and

ensured developmental breakthroughs in the Oil and Gas Sector it regulates,

piloted by the skillful management of the NCDMB, and it will be an economic

drawback to discard it after a decade of excellence. Also, there are in

existence various Ministries to cover each Sector of the economy all having

regulations governing their activities. The application of Local Content is

indeed, a concept that can only be successfully actualized in the Oil and Gas Sector

alone, as records have exhibited, attempting to drag it into the shores of

other Sectors is fated to being an exercise in harmonic futility.

Mr. Oyetola Muyiwa Atoyebi, SAN is one of the most notable professional Nigerian lawyer,

who has distinguished himself in his professional sphere within the country and

internationally. He is the youngest in the history of Nigeria to be elevated to

the rank of a Senior Advocate of Nigeria. At age 34, he was conferred with the

prestigious rank in September, 2019. Mr. O.M. Atoyebi, SAN can be characterized

as a diligent, persistent, resourceful, reliable and humble individual who

presents a charismatic and structured approach to solving problems and also an

unwavering commitment to achieving client’s goals. His hard work and dedication

to his client’s objectives sets him apart from his peers.

As the Managing Partner of O.M. Atoyebi, SAN &

Partners, also known as OMAPLEX Law Firm, he is the team leader of the Emerging

Areas of Practice of the Firm and one of the leading Senior Advocates of

Nigeria in Local Content Law, where he has worked with various key industry

stakeholders and successfully facilitated transactions in the Oil & Gas and

Energy Sector. He has a track record of being diligent and he ensures that the

same drive and zeal is put into all matters handled by the Firm.

by Legalnaija | Sep 16, 2020 | Uncategorized

INTRODUCTION

International sports law has seen

several developments and changes in the last decade, one of such is the radical

change in the Athlete nationality regime and the remodelling of the

international and municipal concepts of citizenship.

As the world is fast becoming a global

village due to the strong influence of globalization, the stringiest

requirement for citizenship and nationality has been relaxed by various nations

in the alarming race to secure top class athletes or seek dominance in certain

sports.

In

the light of this, athletes have been seen to throw nationality and patriotism

to the wind in an emerging world of marketization of citizenship. The International

Olympic Committee (IOC) have also taken steps to regulate and control this

growing tide. In a fair attempt to regulate same, several legislations and

rules have been made and agreed upon to curb and set a standard for nationality

swapping.

This paper shall examine the principles

governing nationality swapping at the Olympic Games.

THE QUESTION OF NATIONALITY

AND CITIZENSHIP

According to the European

Convention on Nationality (1997), nationality can be defined as ‘the

legal bond between a person and a state’.

Furthermore, the definition does not indicate the person’s ethnic origin that

is ones nationality is nowhere connected to one’s ethnic affiliation or

background.

Although National/domestic laws are

provided to regulate acquisition of nationality status by various states,

International Federations (IF’s) also make provision for attainment of

nationality status.

In international law, citizenship is a

reference to the general nationality of a state acquired by one under the

various citizenship laws of a state. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Guarantees the right to swap (change) his/her nationality without deprivation

on any grounds.

It is now no gain saying that the right to swap (change) nationality is one

provided for and protected by International conventions/treaties.

NATIONALITY

SWAPPING UNDER THE OLYMPIC CHARTER EXAMINED

The issue of nationality under the Olympic

Charter is regulated by Rule 41 of the Charter. It is a fundamental

principle that for an athlete to participate/compete at the games such an

athlete must be a national of the country of the National Olympic Committee

(NOC) which is entering such competitor.

Any dispute arising from the nationality of a competitor at the games relating

to the athlete’s state of nationality is resolved by the international Olympic

committee (IOC) Executive Board.

Due to globalization, many athletes

are very much eligible to represent more than one country. Example, Yamile

Aldama, a world class triple jumper, has been a beneficiary of the fluidity in

nationality at the games which has seen her represent three different countries

i.e Cuba at the 2000 games in Sydney, Sudan at the Athens 2004 games and

Britain at the London 2012 games. This dynamic is recognised by the charter in

Bye-law to Rule 41 (1). But it goes further to the state and specify the

conditionality’s for nationality swapping.

The charter provides that where an

athlete (competitor) is a national of two or more countries at the same time,

he (the competitor) may represent either one of them, as he (the competitor)

may elect. Where such an athlete (the competitor) has opted to represent one

country in the Games (Olympics) or in a continental or regional or world

championship (IAAF World Championship for example) recognised by the relevant

International Federation (IF) he may not represented another country unless he

meets the following requirements:

i)

Three years has passed since

the competitor last represented his former country. Note that this period may

be reduced or even cancelled with the agreement of the NOC and IF concerned, by

the IOC Executive Board.

ii)

The competitor must first

change or acquire a new nationality subject to the nationality laws of the new

state.

If the athlete (the competitor) can fulfil the above

stated requirements then he can be eligible to represent his new nation at the

games.

Another

principle worth noting is the status of ‘Stateless Athletes’. Stateless may be as a result of a refugee

status by an athlete where he fled his country of birth and domicile in another

country. In this situation, if the athlete meets the three year waiting period

and can prove he (the competitor) had severed his ties to his country of birth.

Also, where an

athlete is from a state with no NOC, such an athlete is not deemed as

‘stateless athletes’, such athlete will be regarded as an ‘independent

athlete’. The Charter of the Games provides that an athlete must be sponsored

by a country’s NOC. This situation arose with Guor Mamal, a South Sudanese

Marathon runner at the 2012 London Games, he wanted to join the national team

of the United States, his domicile, but he was not a United States citizen and

his country of birth, South Sudan had no NOC, as South Sudan was in its first

year of independence.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the question of nationality amongst athletes

at the games is a fluid one, which gives a power to bigger, richer and well

established countries to offer better welfare and financial packages to

athletes to entice them to represent them at the games. This has served

countries with rich resources but not much talent pool to draw from, thereby

allowing them to deep into the global athlete market to window shop for willing

athletes who are ready to swap nationality for better working and competing

conditions.

On the other

hand, the IOC is also encouraged to make alterations to the procedure for

nationality swap, i.e the waiting years as this is not really important as the

consensual agreement between the athlete, adopting country and the IF concerned

is of utmost importance.

F. E. OROK (Esq)

F. E. OROK (Esq)

Rule

41 Bye-Law (ii) of the Olympic Charter

by Legalnaija | Sep 12, 2020 | Uncategorized

The role played by the Nigerian Bar

Association and lawyers in the development of Nigeria’s economic and societal goals

cannot be overstated. Due to this, the expectations of everyone who

participated in or followed the recent NBA Elections are quite high, a fact

that is not lost on the new officers. The NBA President, Mr. Olumide Akpata, noted

this at his inauguration, when he stated that “As I informed the new national officers during our strategy retreat

last weekend, hitting the ground running immediately will not be enough, we

also need to hit it flying. Nothing short of that would match the expectations

of our members and Nigerians.”

While the new NBA officers have their work

cut out for them, it is important to note that they will not achieve remarkable

success except with the cooperation and support of members of the Bar. The

purpose of this series on NBA Officers, is therefore to ensure that lawyers are

informed of the respective duties of the newly sworn officers to enable easy

communication, and collaboration.

Though the NBA President leads the

Association and is ultimately responsible for the administration of the NBA

under his watch, the ten (10) other officers also play a huge role in the management

of the Association’s affairs.

In this post, we shall therefore be looking

at the duties of the Assistant Publicity Secretary of the NBA. As provided in

Section 5 (k) of the NBA Constitution; the duties of the Assistant Publicity

Secretary shall be as follows:

i.

He/She shall assist

the Publicity Secretary in the performance of his/her duties and shall in the

absence of the Publicity Secretary act in his/her place;

ii.

He/She shall perform

all other duties as may be assigned to him/her by the President or the National

Executive Committee or the Annual General Meeting.

Mr. Ferdinand Naza is the current Assistant

Publicity Secretary of the Nigerian Bar Association. Follow him on Twitter

@ferdinand_naza

by Legalnaija | Sep 11, 2020 | Uncategorized

INTRODUCTION

The Oil and Gas sector of the Nigerian

economy has hitherto, remained the mainstay of the country’s capital value chain

and the most remarkable component of our National Gross Domestic Product. Given

this incontrovertible fact, it has therefore become highly imperative that the

Act be revamped and its provisions brought into compliance with international

industry best practices while still preserving its core objective, which is

provision for the development of Nigerian Content in the Nigerian Oil and Gas

Industry by encouraging participation of Nigerians.

Before the National Assembly, is a

Bill to amend the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content Development Act, 2010,

properly short cited as the Local Content Act (the “Act”). The Act which is

composed of 106 Sections is sought to be amended by the Nigerian Oil and Gas

Industry Content Development (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (HB.838) (the “Bill”). The

move to amend the decade-old Act sprang out of the pressing need to address

certain salient issues which have been either neglected or improperly captured

in the legislation. In a bid to prevent

the enactment of provisions considered inconsistent with the mandate and true

spirit of the Act, the Bill seeking to usher in these amendments has thus, been

subjected to rigorous legal scrutiny to capture enlightened viewpoints that

will allow the fulfilment of its objects before it ascends into law. This paper

is focused on some provisions of the Bill we believe needs to be addressed.

THE

NEED TO DEFINE NIGERIAN INDIGENOUS COMPANIES: FUNDAMENTAL ROLE IN THE

DEVELOPMENT OF NIGERIAN CONTENT

The mandate of the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content

Development Act is primarily to provide for the development of Nigerian

Content in the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry by encouraging participation of

Nigerians. Indeed, the true measure of the success of content development in

Nigeria is in the amount and complexity of works and role played by Companies

wholly owned and managed by Nigerians, whose focus is on developing

Infrastructure and Technology in Nigeria, thereby encouraging profits to be

retained and reinvested into our economy. Consequently, these Companies are

building and developing capabilities towards ultimately exporting Nigerian

products and services, rather than relying on importation, which is an absolute

characteristic of a Nigerian Indigenous Companies.

The focus of the Act

primarily is on Nigerian indigenous companies. Therefore, any amendment to the

Act must be to protect and encourage an environment for exponential increase in

their numbers and rapid growth in size, so as to pull along the Nigerian

economy. Just as the most developed Oil and Gas countries have done, they have

prioritized the interests of indigenous companies by enacting laws that will

foster and encourage their participation on the sector that is driving their

economy. The glass ceiling which is preventing our economic growth will go away

when we prioritize indigenous companies in the dealings of the sector that

corners us the most revenue annually.

The Act has fallen short of providing

a comprehensive definition as to what constitute the entities regarded as “Nigerian Indigenous Companies”, rather it

resorted to using terms such as “Nigerian

Independent Operators” and “Indigenous

Service Companies” in making reference to exclusive and first consideration

to Nigerians as stipulated in the Act. Furthermore, Section 106 (interpretation Section), defines “Nigerian Companies” thus:

“A company formed and registered in Nigeria in accordance with the

provision of Companies and Allied Matters Act with not less than 51 % equity

shares by Nigerians”.

A cursory study of judicial

pronouncements on the definition of what constitutes a Nigerian Company, will

reveal that the meaning provided by the Courts over time, appears to be at a

sharp variance with what the Act envisages, which apparently allows room for

foreign ownership of equity shares in a company considered Nigerian. A

classical case in point, is SIKIRU AGBOOLA LASISI v. REGISTRAR OF

COMPANIES [I176] LPELR-SC.301/1975, where the Supreme Court laid down

the correct test for determining whether a company is a Nigerian association or

not, in these words:

“It is clear from the definition under

Section 16(1)(c) of the Nigerian Enterprises Promotion Decree, 1972 that the

correct test for determining whether a company is a Nigerian association or not

is to discover the owners of its capital and other financial interests. If its

capital and other financial interests are wholly and exclusively owned by

Nigerian citizens, then it is a Nigerian Association. If, however, a portion of

its capital or other financial interest is owned by an alien then, except as

otherwise prescribed by or under the Decree, it is an alien association”. (Underlined

is ours for emphasis).

The Act having defined the term

Nigerian Company makes no further mention of a “Nigerian Company” at all, rather it resorted to various vague variations; “Nigerian Indigenous Operator”; “Nigerian Indigenous Service Companies”;

“Nigerian Indigenous Contractors”; “Nigerian Contractors and Service or

Supplier Companies”, and “Indigenous

Companies” to reference sector participants contemplated under each

relevant provision. Although, the Act has implicitly substituted the term “Nigerian Company” with the

above-mentioned phrases, it nevertheless still intends for the word “indigenous” to remain in the Act so as

to portray its very meaning and objective.

The ambiguity created by the above mentioned words has opened the

provision to different constructions, with stakeholders having to rely on the comprehension

of industry best practice or formally recurring to the interpretation of the Nigerian

Content Development and Monitoring Board (the “Board”) in line with S. 70(1) of

the Act, which permits the Board to “provide

guidelines, definitions and measurement of Nigerian Content and Nigerian

Content Indicator to be utilized throughout the Industry”.

The Bill attempts to cure this ambiguity by proposing to replace

the terms “Nigerian Independent

Operators” with “Nigerian Companies”,

and “Nigerian Indigenous Service

Companies” with “Nigerian Service

Companies”. Regrettably, this has failed to fix the uncertainty occasioned

by the Act, instead, it moved further away from the purpose the Act is designed

to attain, which is the exclusive consideration and participation of Nigerians.

Hence, the proposition by the Bill to erase outright, the term “Indigenous”, nullifies the true meaning

and intention of the Act.

Undoubtedly, what gauges the achievement of content development in

Nigeria and especially in the oil and gas industry, rests on the intricacy and

aggregate of works done and the contributions made by Nigerian domestic

companies concerned with the development of infrastructure, technology and

building galvanized human capacity in Nigeria, thereby assuring the reflow,

retention and reinvestment of profits in our economy. Accordingly, these

Companies are forming and expanding the required competence geared towards the

ultimate exportation and transatlantic

trading of Nigerian goods and services, in place of protracted dependence on

importation, which typifies the precise features of Nigerian Indigenous

Companies.

A brief study of some oil producing countries shows how their

Local Content Laws focus on participation of its citizens in the Oil and Gas Sector

and have reflected same in their laws. We can take a cue from our sister

nation, Ghana, having passed a

similar Law three years after the enactment of the NOGICD Act. The Petroleum (Local Content and Local

Participation) Regulation, 2013 (Ghana), passed in 2013, was enacted with

the purpose of enhancing the capacity of indigenous Ghanaian companies and to

promote their participation in the Oil and Gas Industry.

Regulation 49 of the country’s Petroleum (Local Content and

Local Participation) Regulations, 2013, defines an “indigenous Ghanaian Company” as

“A company incorporated under the Companies Act, 1963 (Act 179)

that: a) has at least 51% of its equity owned by a citizen of Ghana; and b) has

Ghanaian citizens holding at least 80% of executive and senior management

positions and 100% of non-managerial and other positions”.

Similarly, resource rich countries;

Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi-Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) etc. also focus

on local content requirements to maximize the gains of foreign participation in

their Oil and Gas Sectors. The aim is to provide opportunities for local

industries to participate in Oil and Gas activities. Although, several of these

countries do not exactly define the term “local” in their Local Content

Regulation (LCR), generally it means; nationals, and companies owned, or

majorly controlled by nationals.

It is owing to this prevailing reason, that Nigerian Indigenous

Companies must assume a central place within the covers of our Local Content

Act. Therefore, any amendment to it must be anchored on providing and

encouraging an atmosphere for a flooding increase in their numbers and rapid

growth in sizes, in order to redefine the Nigerian economy.

This work recommends that the term “indigenous” be retained and

consequently, the interpretation Clause of the Bill should interpret “Nigerian

Indigenous Companies” to mean;

“A company with

100% equity and assets owned by Nigerian Citizens with its head office/parent

company located in Nigeria”.

It is only a clearly worded and purpose-driven definition of this

kind that can adequately foster the existence of a truly Nigerian Indigenous

Company and guarantees an all-round local content development in our dear Oil

and Gas Sector.

INCREASE OF

PERCENTAGE TO BE CONTRIBUTED TO THE NIGERIAN CONTENT DEVELOPMENT FUND

The

Act makes provision for the establishment of a Nigerian Content Development

Fund (the “Fund”) under Section 104(1),

for the purposes of funding the implementation of Nigerian content development

in the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry. In other words, it is provided to ensure

the absolute achievement of the goal for which the Act was enacted in the first

place.

Having

so established the Fund, Section 104(2)

of the Act further categorically spells

out the major source from which the fund will be generated and placed at 1%

deductible at source, of every awarded contract to any of the listed entities

who are concerned with all the goings-on in the Upstream Sector of the Nigerian

Oil and Gas Industry, to be paid into the fund. This arrangement has worked

perfectly well for the fund itself and provided a considerable measure of ease

to all concerned parties in the undertaking of their business operations within

the spheres of the industry.

Conversely,

the Bill by virtue of a new Clause 105

(2) proposes a coinage of this provision, such that the major source of the

fund will now be derived from the deduction of 2% at source of every contract

awarded to any operator, contractor, subcontractor, alliance partner or any

other entity involved in any project, operation, activity or transaction in the

Upstream Sector and designated Midstream and Downstream projects operation of

the Nigeria Oil and Gas Industry, which is to be paid into the fund.

Flowing

from the foregoing is the overt fact that, while the initiative to extend the

spectrum of application of this provision by the Bill to include “designated Midstream

and Downstream projects operation” is by far a commendable one, as it will

automatically open the floodgate of more income pooling into the fund and in

turn, speed up the implementation of content development in the industry.

However, an increase in the contributory funds from 1% to 2% of every contract

awarded, is outrageous and can be regarded as double taxation on so many

levels. It can be argued that the sector is indeed already significantly

overburdened by a plethora of levies and fees; Education tax, Nigeria Police

Trust Fund (NPTF) levy, Nigerian Capital Development Fund (NCDF) Levy, Niger

Delta Development Commission (NDDC) Levy, Nigerian Export Supervision Scheme,

and Offshore Safety Permit, others include Cargo & Stevedoring Dues, Waste

Reception Facilities Levy, Value Added Tax among others, and the proposed

minimum of 0.5 per cent of participants respective gross revenues for Research

& Development (R&D) activities in Nigeria. Industry Stakeholders have

expressed concern that any additional financial imposition as proposed by the

Bill on the industry, will very negatively impact Nigeria’s competitiveness and

affect the viability of projects and investments.

It is a bit alarming that while the Government

seems to want to

achieve lower costs, it is imposing

multiple taxes and levies. This is without consideration for high security

costs, assets fixing and environmental remediation costs, that follows asset damages. The Government is expected to support the

industry to remain a viable partner for the economic development of Nigeria and

not impose unnecessary burden.

In

addition, an increase to 2% smacks of unaccountability, given that there are no

detailed developmental returns on previous contributions to the Fund, published

by either the Board or any other responsible regulatory body. It then becomes

valid to recommend that contributions be retained at 1% as provided in the Act.

APPLICATION

OF THE NIGERIAN CONTENT DEVELOPMENT FUND

Unequivocally, the landmark success in the Nigerian economy over the breadth of

the last decade is attributable to the enactment of the Nigerian Oil and Gas

Industry Content Development Act. The

proposed amendment, which is channeled along the lane of enhancing better

participation of Nigerian citizens, rests on how the industry, local businesses

and state institutions create the needed synergy to overcome the obstacles

militating against the actualization of local content opportunities. `

Clause 105(3) of the Bill provides that;

“The Fund shall be managed by the

Nigerian Content Development and Monitoring Board and employed for projects,

programmes, and activities directed at increasing Nigerian Content in the Oil

and Gas Industry.”

While it can be argued that the

reasoning behind the above clause is progressive, however, it has merely

replicated the provision of the same clause it seeks to substitute, which fails

to address the evident flaw in the application of the fund.

The resources released for funding by

the Board is commendable in most cases but usually are totally insignificant

for some projects. Bringing into account the yearly generated revenue of the

Board, which is earmarked at $360 million from commercial ventures for the year

2020 alone,

it will be most ideal to allocate a percentage of the yearly generated revenue

to the advancement of indigenous companies; large projects, laudable

programmes, capacity building solutions, activities and services of robust

advantage to indigenous companies from whose operations the source of the

generated fund is derived.

Therefore, in order to realize and meet the full objectives of the Fund, for the purpose of

unceasing advancement in the Sector, at least one major project considered

instrumental to the exponential expansion of indigenous companies should be initiated

and executed in the industry, every fiscal year. Thus, not only would it be

highly profitable to set aside a minimum percentage of the total generated

contribution to be spent on projects each year, but it will also prepare the

fertile ground for the acceleration of these companies into the league of their

counterparts with multi-national repute, the economy will be better enriched,

and the multiple returns can then be directed towards stretching the boundaries

of research and development in the industry and even ultimately financing the

process of diversifying into and promoting other sectors in the not too long

run.

Similarly, the Board

should through the Fund, provide

low-Interest Loans to Nigerian Indigenous Companies operating in the Upstream

Sector, to enable them deliver services at competitive pace, intentionally proceed on ceaseless capacity building programs for local

companies in order to both build and boost the right structures to enable them

compete favorably in the Industry, ensure effective enforcement of the

Act to enhance in-country value creation, retention, reinvestment, and

generation of employment for Nigerians

across the Industry value chain, especially at such a time when the revenue

accruable to the Federal Government from other key sectors of the economy is

degenerating at an alarming rate.

Suffice it then to assert that, the provision of Clause 105(3) is

the key to attaining all of these promising potentials which the whole

amendment process portends for the Oil and Gas industry in particular and the

economy as a whole, only if it is redrafted to encapsulate the pertinent

enabling words in the manner described hereafter:

“The Fund shall be managed by the Nigerian Content Monitoring

& Development Board, and 50% of the total generated fund thereof shall be

employed for projects, programmes and activities beneficial to Nigerian

Indigenous Companies and directed at increasing Nigerian content in the Oil and

Gas Industry”

The Local Content Development Fund can only serve its true purpose

if applied to the right course, and the Act must state this in no uncertain

terms.

CONCLUSION

The Bill cannot afford to reenact the

shortcomings it is meant to eliminate. It is therefore required at this crucial

moment for our Legislators to ensure that the Bill underway, is cleared of all

the ambiguities, irregularities, and shortfalls replete in the subsisting

principal Act. A carefully thought amendment of the Act is vital to crystalize

the core intentions of the initial drafters of its letters. While this is being

done, we must balance the interests of the stakeholders in the sector. An

increase in the contributory funds will be burdensome on the already over taxed

stakeholders.

Damilola

Vordah Imong is with Messrs O. M. Atoyebi, SAN

& Partners (OMAPLEX LAW FIRM) where she works in the Corporate and

Commercial Department of the Firm. She has an in-depth understanding of the Oil

& Gas and Energy Sector and has worked with various key industry

stakeholders and facilitated several transactions.

by Legalnaija | Sep 8, 2020 | Uncategorized

There is some confusion

amongst human resources professionals and in-house counsel about the validity

and effect of an employee’s notice of resignation that is short of the period

agreed in the employment contract. Corollary to the foregoing is the issue

regarding whether an employer can reject an employee’s resignation letter for

any reason, including ongoing investigations or disciplinary proceedings

against the employee or inadequacy of the length of notice or other reasons of

the employee’s non-compliance with the employment contracts. In practice, many

employers include the power to reject an employee’s resignation letter in their

#HR policies or Employee Handbook without seeking legal advice on the propriety

of such power.

In law, every employee has

absolute right to resign at any time before termination of, or dismissal from

an employment. An employer has no discretion on whether to accept or reject a

resignation letter. Also, it is immaterial that the employer did not issue a

formal reply or acceptance of the resignation letter. The Courts have held that

all the employee needs to show is that the employer received the resignation

letter and that a rejection letter or email from an employer is an evidence

that the employer received the resignation letter. Whether the length of notice

of resignation is adequate or inadequate, once an employee indicates an

intention to leave an employment, any attempt by an employer to reject that

move or hold the employee down would amount to forced labour and would be

contrary to all known labour standards. In fact, the Court in Taduggoronno

v. Gotom [2002] 4 NWLR (Pt. 757) 453 CA specifically held that no

employer can prevent an employee from resigning from its employment to seek

greener pastures elsewhere.

The only point that needs to

made separately, in addition to the above, for emphatic purpose, is that an employer

cannot dismiss or terminate the employment of an employee who has given a

notice of resignation, notwithstanding the fact that he remains with the

employer during the notice period. This is because a notice of resignation

takes effect from the date it is received by the employer, not on the last

working day as erroneously believed by some employers who still engage in

post-resignation termination or dismissal.

What then is the

effect of inadequate notice of resignation? The

courts have held in Adetoro v. Access Bank Plc and many

other similar cases that where the length of notice of resignation given by an

#employee is less than the period agreed in the employment contract, then, the

notice is deemed to be with immediate effect. So, where, for instance,

the contract provides for termination or resignation by one (1) month’s notice

or salary in lieu, any notice that is short of the agreed period

will amount to RESIGNATION WITH IMMEDIATE EFFECT.

In law, the implication of

“Resignation with immediate effect” vary, depending on whether

the reason for exiting a company is #resignation or #retirement. Resignation

with immediate effect gives the employee the right to leave the employment

immediately and automatically, without any benefit and subject to the employee

paying his outstanding indebtedness (if any) to the employer. Please note that

the fact there is an outstanding indebtedness owed to the employer does not

entitle the employer to insist that the employee must continue to work for the

employer. It merely gives the employer the right to enforce its contractual

right to recover the amount owed. Retirement, however, does not appear to

confer on a retiring worker such a right to leave service immediately and

automatically. In OSHC v. Shittu [1994] 1 NWLR (Pt. 321) 476 CA,

the Court of Appeal (Benin Division) opined that a notice of voluntary

retirement does not entitle the employee to leave the employment immediately or

automatically, and that he or she would still remain in the employer’s service

(especially where the notice is rejected by the employer and the employee

returns to work).