by Legalnaija | Feb 17, 2022 | Uncategorized

A contract of employment is a contract between an employer and employee in which the terms and conditions of employment are stated. The term “employee” denotes anyone who is employed under a contract of employment for remuneration and an employer is such person who employs an employee.

An employment contract is an agreement which carries with it an obligation to pay wages in return for service and a corresponding right of control on the part of the employer. Before an employer/employee can make claims under the contract of employment, such party must prove that the existence of a contractual relationship. A contract of employment can be oral, written, or partly oral and written; it may even be inferred or implied from the conduct of the parties, though most contracts of employment are either oral or written.

Usually a contract of employment contains the following clauses;

- Name of parties

- Address of parties

- Date of commencement

- Salary and emoluments

- Work hours

- Non – Compete clauses

- Ownership of intellectual property

- Vacation and Annual Leaves

- Termination of Employment, and much more.

On Legalnaija, you can create and download your own Employment Contracts and Agreement in less than 5 minutes and for a small fee. All you need do is;

- Visit https://app.legalnaija.com/shop/templates

- Select Tenancy Agreement

- Answer the questions

- Make payment

- Download your agreement

Through this innovation, we have made getting Tenancy Agreements, easier, cheaper and faster. Most especially all our Templates are drafted by expert lawyers.

@Legalnaija

www.legalnaija.com

by Legalnaija | Feb 16, 2022 | Uncategorized

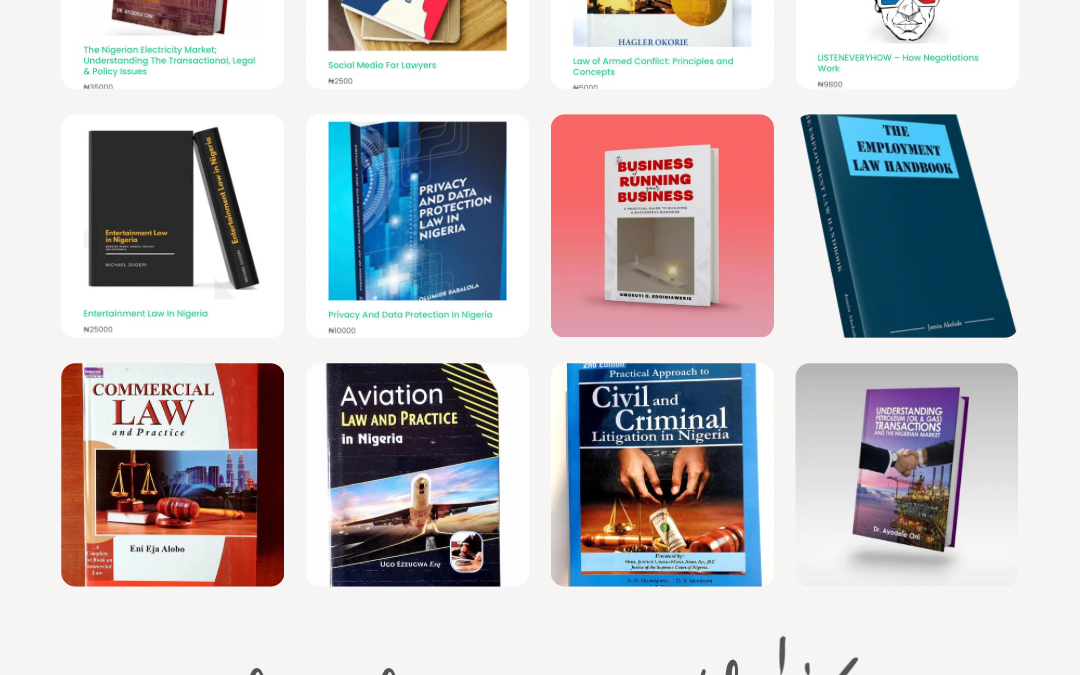

If you want to impress your clients and get the briefs pouring in this year, there are 12 books all Nigerian lawyers must have in their library, and the Legalnaija online bookstore has curated these books for you. See the list below;

- LISTENEVERYHOW – How Negotiations Work (₦9,800)

- Privacy And Data Protection In Nigeria (₦10,000)

- The Employment Law Handbook (₦15,000)

- The Nigerian Electricity Market; Understanding The Transactional, Legal & Policy Issues (₦35,000)

- Understanding Petroleum (Oil & Gas) Transactions and the Nigerian Market (₦50,000

- Social Media For Lawyers (2500)

- Aviation Law And Practice In Nigeria (₦14,000)

- Civil And Criminal Litigation In Nigeria (₦9,500)

- Commercial Law And Practice (₦10,000)

- Entertainment Law In Nigeria (₦25,000)

- Law of Armed Conflict: Principles and Concepts (₦5,000)

- The Business of Running Your Business (₦5,000)

You can order any of these books from the convenience of your device and get it delivered to your doorstep easily. All purchases in Lagos are delivered next day, while those outside Lagos are delivered within 1 – 3 working days.

To make your purchase, visit www.legalnaija.com/shop and to chat with a customer care agent, you can call, text or Whatsapp on 09029755663.

Remember, we are rooting for you.

by Legalnaija | Feb 13, 2022 | Uncategorized

As we celebrate the 30th anniversary of Sierra Leone’s 1991 national Constitution, here are ten (10) interesting facts about the constitution:

- No one can be taken to court for any offence for which he has previously been convicted for by the court. Similarly, if he has been acquitted (freed) by the court from that offence he cannot be taken to court again for the same offence. Section 23(9)

- The constitution gives every Sierra Leonean the right to bring a court action before the Supreme Court to seek redress if any of their fundamental rights have been infringed upon by any person or institution. Section 28

- The President of the Republic of Sierra Leone can pardon any person for a crime he/she may have committed if the person has been tried for that crime by the court and found guilty of the said crime. The power is under the prerogative of mercy. Section 40 (4)(e)

- The constitution states that no person shall hold office as President for more than two terms of five years each, whether or not the terms are consecutive. Section 46(1)

- The Vice President is the Chairman of the Police Council in Sierra Leone. The Police Council advises the President on all matters relating to the Police, internal security and the appointment of the Inspector General of Police. Section 156 (1)

- No one can bring a civil or criminal court action against a Member of Parliament because of what the Member of Parliament said during Parliamentary proceedings. Section 99(1)

- No one can bring an action against a Judge for any matter or anything he does whilst performing his judicial functions. Section 120 (9)

- The 1991 constitution states that every court must give judgments or rulings not later than three months after the close of the case and submission of arguments and the court must provide copies of any judgment or ruling delivered to the parties involved. Section 120 (16)

- The Supreme Court is the only court which can depart from its previous decisions when it appears right to do so and all other courts are bound to follow its decision. This means a future Supreme Court can disagree with what the present Supreme Court has held to be the law. Section 122(2)

- A Judge shall not while he continues in office as a judge, hold any other office where he will make profit or earn emolument, whether by way of allowances or otherwise, whether private or public, and either directly or indirectly. Section 138(4).

Babatunde Johnson is a law graduate from the University of Sierra Leone, Fourah Bay College and he is currently awaiting admission to the Sierra Leone Law School. He is also a legal content creator and Co- Founder at Salone Law Centre.

Babatunde Johnson is a law graduate from the University of Sierra Leone, Fourah Bay College and he is currently awaiting admission to the Sierra Leone Law School. He is also a legal content creator and Co- Founder at Salone Law Centre.

by Legalnaija | Feb 2, 2022 | Uncategorized

Every lawyer before the appellate court craves for a consensus from the judges in the panel, this is the norm and dissent is a departure from what is conceived to be the norm. Dissent is not a concept unique only to the legal system, it is part of our daily lives which is why the famous writer Mark Twain said:

“Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.”

I have on few occasions witnessed the delivery of dissenting judgments and though I am not in agreement with all of them yet I admire the courage to dissent even in the face of probably offending colleagues and those who expect a consensus judgment.

This topic of dissent has always been an enigma to me and as I set on this journey to research on how far and how much our appellate courts have embraced it, I shall first endeavor to address the views of distinguished authors on dissenting judgments.

Former Chief Justice of the United States of America Harlan F. Stone in a letter to the Columbia University in 1928 described dissent in the following manner:

“A dissent in a court of last resort is an appeal to the brooding spirit of the law, to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision may possibly correct the error in which the dissenting judge believes the court to have been betrayed

Judges are not there simply to decide cases, but to decide them as they think they should be decided, and while it may be regrettable that they cannot always agree, it is better that their independence should be maintained and recognised than that unanimity should be secured through its sacrifice.[2]”[Emphasis Mine]

I agree with the Learned Chief Justice and as I have seen in cases with dissenting judgment, the dissent points out to the losing party that the judgment may be an error and may be worth another try in a higher court and if not possible, hope that the law will change in the future to reflect the dissent as held by the dissenting judge. A consensus does not give that hope.

Louis Blom-Cooper and Gavin Drewry in their 1972 article Final Appeal – ‘A study of the House of Lords in its judicial capacity’[3] described dissent of a final appeal as:

“the most apparently poignant judicial tragedy in a legal system founded upon the dramatic conventions of certainty and unanimity”.

A strong condemnation indeed, certainly from advocates of unanimity but I do not agree with the view that a dissent signals a judicial tragedy. Their views may seem to my mind to be nothing short of an endorsement of the herd mentality.

Justice White in the American Supreme Court case of Pollocks v Farmers Loan and Trust Co. (1895)[4] said:

“[the] only purpose which an elaborate dissent can accomplish, if any, is to weaken the effect of the opinion of the majority, and thus engender want of confidence in the conclusion of courts of last resort”.

In the case of Liversidge v Anderson and another [1942][5], the majority of the Law Lords gave a judgment by applying a subjective interpretation to the Defence (General) Regulations 1939 thus allowing the Secretary of State to exercise broad powers by detaining anyone he reasonably believes to be a threat to national security.

Lord Aitkin disagreed and he gave us what we now have as the most popular dissenting judgment in the commonwealth legal system in the following words:

“I view with apprehension the attitude of judges who, on a mere question of construction, when face to face with claims involving the liberty of the subject, show themselves more executive-minded than the executive. Their function is to give words their natural meaning, not, perhaps, in war time, leaning towards liberty…’ in a case in which the liberty of the subject is concerned, we ‘cannot go beyond the natural construction of the Statute.

In this country amidst the clash of arms the laws are not silent. They may be changed, but they speak the same language in war as in peace. It has always been one of the pillars of freedom, one of the principles of liberty for which on recent authority we are now fighting, that the judges are no respecters of persons and stand between the subject and any attempted encroachments on his liberty by the executive, alert to see that any coercive action is justified in law. In this case I have listened to arguments which might have been addressed acceptably to the Court of Kings Bench in the time of Charles I.

I protest, even if I do it alone, against a strained construction put upon words with the effect of giving an uncontrolled power of imprisonment to the Minister. To recapitulate. The words have only one meaning: they are used with that meaning in statements of the common law and in statutes; they have never been used in the sense now imputed to them: they are used in the defence regulations in the natural meaning: and when it is intended to express the meaning now imputed to them, different and apt words are used in the defence regulations generally and in this regulation in particular.” {Emphasis Mine]

Not swayed by popular opinion or by the persuasion of those who have read his draft[6] and armed with the breastplate of independence, he delivered a dissenting judgment believing he was doing the right thing.

He was justified 38 years later, confirming the words of Chief Justice Stone with regards to the hope that someday in the future a later decision may correct the error of the law as the dissenting judge may have opined.

Lord Diplock delivering the judgment in Inland Revenue Commission v Rossminister & Others (1980)[7] said:

“For my part I think the time has come to acknowledge openly that the majority of this House in Liversidge v. Anderson were expediently and, at that time, perhaps, excusably, wrong and the dissenting speech of Lord Atkin was right.” [Emphasis added]

For some practitioners, there is no need to bother with dissenting judgments but I believe a better approach is to read the judgments as a whole and to form your views on the opinion of the Learned Justices. Every Practitioner will understand the beauty of this advice when faced with the dilemma in the case of The Estate of Khalilu Jabbie v Skye Bank (SL) Ltd MIsc. App 45/2014 SLCA (unreported)[8].

I am sure many will agree with me that our present legal system is in desperate need of dissenting judgments. Has that been the case? Have we had enough such dissents to qualify the system to be reflective of judicial independence, freedom of expression and a transparent decision-making process? These are all the questions I might provide answers to in the succeeding parts of this article for we must all agree that the right to disagree is a right that brooks no dissent.

In the words of Justice Ginsburg of the US Supreme Court who is known to have written few dissents in a 2009 speech said:

“My experience teaches that there is nothing better than an impressive dissent to lead the author of the majority opinion to refine and clarify her initial circulation.”

Bernard Eldred Jones Esq is a Barrister and Solicitor in Sierra Leone. He holds a Master of Laws in Banking and Finance Law (UOL), Post Graduate Diploma In Commercial and Corporate Law, Bachelor of Social Sciences specializing in Economics from Fourah Bay College University of Sierra Leone and Bachelor of Laws (LLB) Hons (London)

He was called to the Sierra Leone Bar in 2009. He is a private practitioner.

by Legalnaija | Jan 20, 2022 | Uncategorized

The Justice Sector Summit 2022 themed – “Devising practical solutions towards improved performance, enhanced accountability and independence in the justice sector” is scheduled to hold on Tuesday 25th January 2022.

The Summit is organised by the Nigerian Bar Association and the Justice Research Institute; in collaboration with the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Justice Reform Project. It is expected that the Summit will proffer practical and actionable solutions that will be implemented by all stakeholders, leading to significant and tangible improvements in the efficiency of the justice sector.

Registration to attend the Summit virtually is now open to Judicial Officers and Lawyers and will close on Friday, 21st January 2022. The organising committee will email the event link and other relevant information to all registered participants on or before Monday, 24th January 2022. If you have any questions, you can reach the organising committee via email at akinyemiaremu@gmail.com or via telephone on 08057765897

Registration here https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfyK6oroc0hkbYUHqKy3eO5j67kT0pFmsElTCP_TKpP0QV_Xg/viewform

#justicesummit #nbajusticesummit #legalnaija

by Legalnaija | Jan 20, 2022 | Uncategorized

On 15th March 2011, one Ifeanyi Blessing was arrested at a motor park in the village of Ojo- gbonro Kanbi in Ilorin East Local Government Area of Kwara State with a bag containing dried weed suspected to be Cannabis sativa. On 21st March 2011, Ifeanyi Blessing was arraigned before the Federal High Court, Ilorin on a three-count charge for unlawfully dealing with 2.4 kilograms of Indian Hemp and unlawful possession of 15.4 kilograms of Indian Hemp. She pleaded not guilty to each count. The Trial Court, in its judgment, discharged and acquitted Ifeanyi Blessing on Counts 1 and 3 which bordered on unlawfully dealing in Indian Hemp but was found guilty on Count 2 which bordered on unlawful possession of the substance and sentenced to fifteen (15) years imprisonment. This decision was upheld by both the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court.[1]

The presence of the British in Nigeria for centuries has left an indelible mark on our legislative and judicial system. Nigeria’s legal framework has a long history, dating back to the British colonization of the nation in the early 1900s when Nigeria became a British Protectorate. During this period, they promulgated laws and established correctional facilities and mediums based on their judicial system. The Received English law is made up of rules of Common Law, Doctrines of Equity and Statutes of General Application. Enactments, such as the Wills Act of 1837, Fatal Accident Act of 1864, among others, are examples of Statutes of General Application.

The British colonial administration did not consider the Nigerian social, cultural and economic background before imposing their laws on the Nation. After independence, the composition of the Nigerian legislature became fully indigenuous and the expectation was that the legislature would review received foreign laws and enact laws to reflect the realities of the Nigerian society.

It is worthy of note that one of the key attributes of a good law is that it must be dynamic and evolve to meet the growing and emerging curves in human civilization and cross-interaction. Hence, it is expected that Nigerian laws would similarly grow with time, and reflect international best practices. The United States of America for example, being a former colony of the United Kingdom themselves, has taken steps over the years to improve and change its laws to reflect its realities and represent international best practices.

In the 20th Century, it was believed that undesirable behaviours could be eliminated by rigorous law enforcement. This led to the criminalization of some personal behaviours including some sexual practices, gambling, gun possession, and the use of alcohol and drugs which were previously beyond the reach of the law; the most noteworthy example being the prohibition of alcoholic beverages in the United States from 1919 to 1933. However, starting from the 21st Century, the bans on these activities were lifted, and most of them were decriminalised.

In 1937, through the Marijuana Tax Act, Cannabis production was prohibited in the United States of America[2]. However, today, 16 States, including Washington D.C have legalised the use of Marijuana for adults, while 36 States have legalised its medical use[3]. This change was influenced by the prevalence of its use in America and globally.[4]

This article focuses on the laws regulating or rather, criminalising the cultivation and processing of Cannabis in Nigeria. It interrogates Nigeria’s legislative growth regarding drugs, particularly Cannabis, and questions whether there is need for a change in the way we approach the topic. It ends by highlighting the costs of these laws, considering the human capital and potential economic activities involved.

2.0 THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR CANNABIS REGULATION IN NIGERIA

British colonial authorities engaged in small-scale Cannabis cultivation from as early as the 1930s[5] in their colonies, including Nigeria, whilst its cultivation, use, processing and importation had been banned in the United Kingdom by virtue of the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1926 that included Cannabis as a dangerous drug[6]. In 1935, the Dangerous Drugs Act came to force in Nigeria, criminalising the use of Cannabis in Nigeria.

Nigeria’s current laws, both received and enacted after independence, criminalize the possession, transaction, and use of Cannabis. Some of the laws expressly addressing this under Nigerian law include:

- The National Drug Law Enforcement Agency Act, Cap N30 Laws of the Federation, 2004. (“NDLEA Act”).

Section 11 of the NDLEA Act provides for the offence of production, processing, sale, and importation of hard drugs, which includes Cannabis. It also provides that upon conviction, the accused person is liable to be sentenced to life imprisonment.

The section also provides for the offence of possession and the use of Cannabis. The accused person upon conviction is liable to imprisonment for a term not less than fifteen years but not exceeding twenty-five years.

Furthermore, Section 19 of the NDLEA Act states that anybody in possession of Cannabis without valid permission is guilty of an offence under the Act and faces a penalty of imprisonment of not less than fifteen years and not more than twenty-five years, if convicted.

- Dangerous Drugs Act, Cap. D1, Laws of the Federation, 2004 (“DDA”).

Section 2 of the DDA defines Indian Hemp thus:

- Any plant or part of a plant of the genus cannabis; or

- The separate resin, whether crude or purified, obtained from any plant of the genus cannabis; or

- Any preparation containing any such resin, by whatever name that plant, part, resin, preparation may be called.

Section 10 of the DDA, includes Indian Hemp as a kind of dangerous drug.

The DDA, in general, governs and regulates the licensing and importation of drugs classified as dangerous under the Act. The Act also establishes penalties for violations or non-compliance with the regulations contained in the Act.

- Indian Hemp Act, Cap.I6, Laws of the Federation, 2004 (“IHA”).

According to Section 5 of the IHA, any person guilty of possessing and smoking Indian hemp shall be liable on conviction to imprisonment for a term of not less than four years without the option of fine.

Section 7 of the IHA makes it illegal to utilize a premises for the sale, procurement, processing, manufacturing, or smoking of Indian hemp. According to the section, anybody who occupies such premises and consents to the use of the premises for the sale, procurement, processing, cultivation, or smoking of Indian hemp is guilty of an offence and liable upon conviction to a ten-year sentence without the option of a fine.

There are also, a plethora of decided cases of the Supreme Court, convicting persons for the unlawful possession, transaction of, and use of Cannabis (Indian hemp). For instance, the case of Chukwudi Oyem v. the Federal Republic of Nigeria delivered in April 2019, and reported in [2019] 11 N.W.L.R Part 1683, where the appellant was charged at the lower court on one count charge, of transporting 103.1 kilograms of Indian hemp (Cannabis Sativa). After the trial at the trial court, he was convicted and sentenced to 5 years’ imprisonment. He appealed to the Court of Appeal, where his appeal failed, and thereafter to the Supreme Court which also dismissed his appeal. Also, in the case of Blessing v. FRN[7], the Court, per K.M. Kekere- Ekun JSC reiterated the ingredients for convicting a person under the NDLEA act thus:

“1. That the substance was in the possession of the accused;

2.That it was knowingly in his possession;

3.That the substance is proved to be Indian Hemp (cannabis sativa); and

4.That the accused was in possession of the substance without lawful authority.”

Similarly, in the cases of the Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Faith Iweka (2013) 3 N.W.L.R. Part 1341; Umar v. FRN (2018) LPELR-46336(SC); and Nwadiem v. FRN, (2018) LPELR-44506(CA), the Court convicted and sentenced the appellants for the offence of possession of Cannabis.

It was reported by the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) that a total of 126 Nigerians across 14 states in Nigeria were sentenced to various jail terms for drug-related offences between January and February 2021.[8] Also on the 7th of February, 2021, the NDLEA reportedly intercepted marijuana worth an estimated N1.4billion. The question therefore is – “Could the country have properly injected the N1.4 billion worth of Cannabis in our own pharmaceutical industry?”

The above examples depict the cost of maintaining these Cannabis laws by the Government, and ensuring their efficacy. This is so as monies, time and labour expended in tracking, fighting and prosecuting Cannabis related crimes are enormous. The cost also continues when the government has to take care of these convicted persons using taxpayer money for long durations. In a 2011 report by the Transform Drug Policy Foundation , it was reported that an estimated $100 billion was spent globally on drug law enforcement[9]. Although there are no readily available estimates in Nigeria, it is obviously conceivable that the costs would run into billions of naira.

On the whole, this disquisition argues that the limited resources devoted to this system imposed on us by antiquated laws, either directly or indirectly, should be reallocated to the development of a viable Cannabis industry for the benefit of the nation, even if we are playing catch up.

3.0 LEGALIZATION OF CANNABIS AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY

In reviewing a series of World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations on Cannabis and its derivatives, the WHO on Narcotic Drugs (CND) zeroed in on the decision to remove Cannabis from Schedule IV of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs — where it was listed alongside specific deadly, addictive opioids, including heroin, recognized as having little to no therapeutic purposes.[10]

The 53 Member States of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (the United Nation’s central drug policy-making body) voted to remove Cannabis from Schedule IV of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

Thailand, a conservative nation like ours took a huge step by enacting the Narcotics Act 2019, which currently regularizes the use and purpose of Cannabis in Thailand. It has been forecasted that Cannabis could generate about 8 Billion Thai Bhat for the Pharmaceutical industry in Thailand.[11]

4.0 THE ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF THE LEGALIZATION OF CANNABIS

The economic benefits of legalizing Cannabis are boundless. It is remarkable to state that the Cannabis industry in America made a whopping $13.6 billion in 2019, with at least 340,000 jobs across its value chain, while Cannabis companies have raised $118.6 billion in the same year[12]. This number has taken a hit, due to the coronavirus pandemic, with the industry managing only $20billion worth of business in 2020[13]. However, market analysts are projecting an upward spiral, with the US market expected to generate at least $85 billion by 2030.

Similarly, the Canadian Cannabis market is projected to soar, with the legalization of its recreational use vide the Federal Cannabis Act. Canada has expanded its horizons in this regard and Canadian licensed companies are now aggressively pursuing this business in a bid to dominate the space. This indeed shows potential for immense foreign direct investment coming into Nigeria, which will have a positive bearing on our GDP.[14]

The Cannabis market continues to grow past its conventional use. A lot of products have been developed and are being developed from Cannabis, from edibles including cookies, chocolates and gummies to beverages, and combustibles used for materials, all for recreational usage, to wellness products like oils, hair creams, capsules, cosmetics, beauty and skincare products, to the more regulated medical Cannabis industry, being a feature for drugs aimed at alleviating epilepsy, glaucoma, multiple sclerosis, chronic pain, depression, and for chemotherapy among others.

It is believed that the Cannabis industry would continue to grow tremendously and that through purposive legislative, regulatory support and control, Nigeria could be a world leader in that market. Nigeria has a fertile land for the cultivation of a variety of Cannabis and a budding unemployed youth to man the factories. This would, however, require the buy-in of all stakeholders in Nigeria, particularly the Government, being regulators. The first step to the realisation of this objective would be to finance top-end research into the Cannabis potentials of Nigeria and identify the products to be developed from Cannabis. There would be a need to enact a law in this regard or overhaul the extant Indian Hemp Act, Dangerous Drugs Act, the NDLEA Act and the NAFDAC Act to move from a criminalization-based approach, which is Colonial in nature, to that of a controlled economic perspective.

Therefore, the focus should be on standardization, licensing, the distinction between medical, recreational and other ancillary usages, and product streamlining; consumer centred compliance measures from the seed to sale chain by licensed companies, and the effect on public health. Policies should be based on wide research and evidenced clinical trials.

Away from revenue generation, the Cannabis industry has proven to be a viable labour and employment system. The Cannabis value chain involves large scale farming, factory settings, dispensaries and nurseries, all potentially serving as an employment net for the Nigerian youths, a lot of whom are languishing in prisons for Cannabis related offences, induced by lack of employment.

Hence, a reconsideration of the cultivation and commercialization of Cannabis in Nigeria will be a potentially economic-booming and poverty-alleviating measure.

5.0 CONCLUSION

Nigeria has great potential to dominate the Cannabis market continentally and amongst other countries outside Africa by growing with the trends. The world is changing, nations of the world are opting for clean energy, and over-reliance on oil in the nearest future could have a negative impact on the economy. Currently, the Nigerian Government expends a huge sums of money and resources to investigate, raid, arrest and prosecute persons associated with the cultivation, transaction or possession of Cannabis in Nigeria. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, a minimum of 9,284 persons were arrested in 2018 adding to the already brimming and chock-a-block correctional centres in Nigeria.

It is thus our considered view that it is high time the government, through its legislative arm, reconsidered the costs of enforcing the laws which criminalise the possession and/or use of Cannabis (among others) in Nigeria against the potential benefits of Cannabis and its cultivation in Nigeria. Where it finds that the latter outweighs the former, after a holistic consideration, the government can develop and build a sustainable legal framework for the regularization of Cannabis usage in Nigeria. We believe that it is much more profitable for the Country as a whole to consider the issue of Cannabis from a commercial perspective than to be stuck in a Colonial state of mind and be left to catch up with the rest of the world.

[1] Blessing v. FRN [2015] 13 NWLR 5.

[2] Nick , J., ‘American Weed: A History of Cannabis Cultivation in the United States’ (2019) 48 EchoGeo < http://journals.openedition,org/echogeo/17650 > Accessed 22 October, 2021.

[3] Jeremy Berke , Shayanne Gal , and Yeji Jesse Lee, ‘ Marijuana Legalization Is Sweeping The US. See Every State Where Cannabis Is Legal’<https://www.businessinsider.com/legal-marijuana-states-2018-1?IR=T > Accessed 22 October, 2021.

[4] Saurav Bhola, ‘Sociological School of Jurisprudence’, <https://blog.ipleaders.in/sociological-school-of-jurisprudence/ > Accessed 28 July, 2021.

Sociological jurisprudence is a term coined by the August Comte (1798-1857) to describe his approach to the understanding of the law. This philosophical approach to law stresses the actual social effects of legal institutions, doctrines, and practices. It examines the actual effects of the law within society and the influence of social phenomena on the substantive and procedural aspects of law. This is also known as sociology of law

[5] “Assessing-Nigeria’s-Drug-Control-Policy” (PDF). Count the Costs. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cannabis_in_Nigeria#:~:text=Cannabis%20in%20Nigeria%20is%20illegal,Oyo%20State%20and%20Ogun%20State Accessed: 30th July 2021.

[6] Porter, Bernard. ‘Empire Ways: Aspects of British Imperialism’. I.B.Tauris. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-85773-959-9.

[7] (2015) 13 NWLR (PT. 1475) 1

[8] NAN, ‘NDLEA Secures 126 Convictions in 2 Months’ < http://www.guardian.ng/news/ndlea-secures-126-convictions-in-2-months-official/ > Accessed 27 July, 2021.

[9] Transform Drug Policy, ‘The Alternative World Drug Report’ < https://transformdrugs.org/assets/files/PDFs/alternative-world-drug-report-summary-2016.pdf > Accessed 27 October, 2021.

[10] David Gabrić ‘UN Commission Reclassifies Cannabis, Yet Still Considered Harmful’ <https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/12/1079132 > Accessed 2 December, 2021.

[11] Thai PBS World’s Business Desk, ‘ Multipurpose Marijuana Could Light Up Another Economic Engine For Thailand’ < https://www.thaipbsworld.com/multipurpose-marijuana-could-light-up-another-economic-engine-for-thailand/ > Accessed 5 May, 2021.

[12] Deborah D’Souza ‘The Future of the Marijuana Industry in America’ <https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/111015/future-marijuana-industry-america.asp > Accessed 7 December, 2021.

[13] George Mahaffey, ‘Why Banks are Finally Nearing a Green Light on Medical Cannabis’ < https://www.citybiz.co/article/47131/why-banks-are-finally-nearing-a-green-light-on-medical-cannabis/ > Accessed 7 December, 2021.

[14] Ibid.

(Author: O. M. Atoyebi S.A.N, Contributors: Ibrahim Wali, John Oladipo, Charles Ali).

by Legalnaija | Jan 13, 2022 | Uncategorized

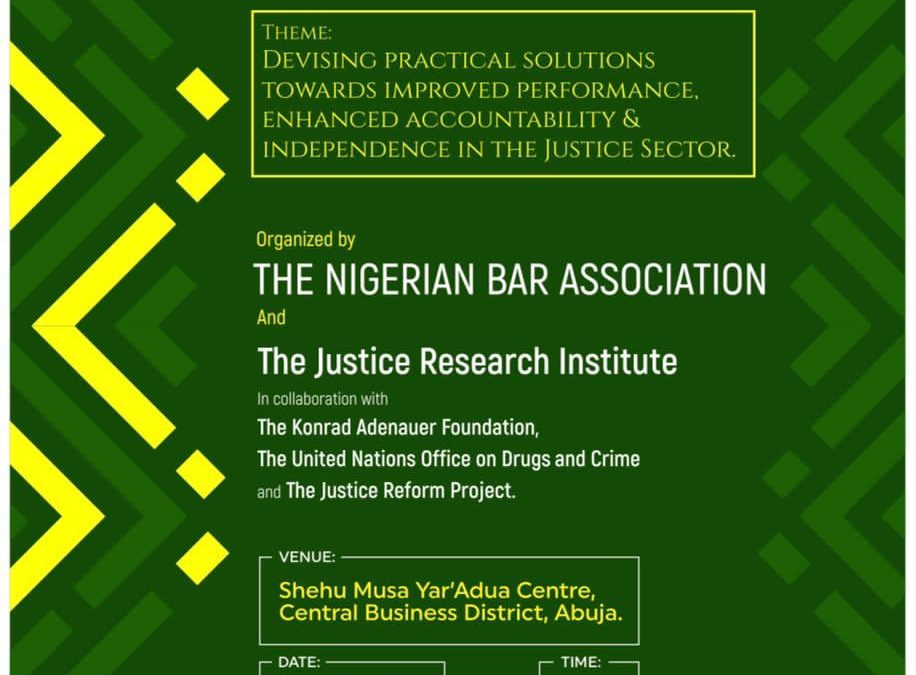

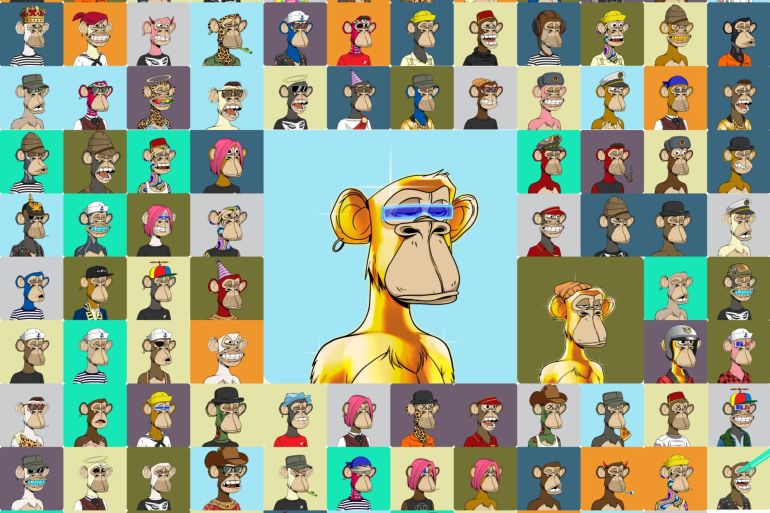

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are the most popular trend in the crypto world right now. Simply put, NFTs are a way to prove digital ownership of online assets. They bear similarities with cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum and other alternate coins which have created an online enthusiasm.

NFTs transform digital works of art and other collectibles into unique, verifiable assets that are easy to trade on the blockchain technology. They are digital assets that depict ownership and are worth whatever a person believes their value is, and can vary widely in what is offered.

Although NFTs are currently speculative assets. Their existence dates back to 2017 when they were first minted on the Ethereum blockchain. According to JPMorgan, the NFT market has grown at an explosive rate as at 2021, with monthly sales hovering around $2 billion.

Nigerians are also moving strongly in the NFT direction. The ownership of digital assets in Nigeria is becoming increasingly popular, according to a report by finders, about 13.7% of Nigerian Internet users own non-fungible tokens (NFTs). This is just above the global average of 11.7% users.

Oyindamola Oyekemi, a 24-year-old Nigerian artist who creates portraits using ballpoint pens, sometimes in 2021, tweeted her drawing of Ethereum co-founder Charles Hoskinson. Hoskinson noticed the tweet and put it up for sale as a non-fungible token (NFT), or unique digital item with its own digital signature. By the end of the month, the tweet was sold for $6,300. Worthy of note is Jason Osinachi who sold two NFTs for $16,227 and $23,633 and thereafter quit his job as an academic librarian at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka to focus on digital arts full time.

The mind-boggling question you may ask is, how can individuals/entrepreneurs benefit from NFT. The sale of an NFT does not mean an ownership of the original work as the Intellectual Property Rights of the creator still reside with him. What the buyer merely owns is a blockchain receipt (digital files) that acts like a receipt showing that the holder owns a version of a work and not the actual NFT and this does not prevent the creator from selling copies of the work to other people.

Given that NFTs are fast becoming mainstream in Nigeria, there are a wide range of opportunities for startups and established businesses in the creative industry such as visual artists, musicians, game designers or art vendors that makes digital arts to test the waters with NFTs.

There are other ways, startups can make an income from NFTs one such way is by creating Digital music, for example, M.I, a Nigerian musician and rapper, last year indicated interest to launch an exclusive NFT collection. Foreign musicians such as Rock band Kings of Leon, also released an album as an NFT and earned more than $2 million from the sales.

The creation of Virtual real estates is gaining traction in countries such as USA, for instance, pieces of land in virtual worlds such as Decentraland are purchased and are sold at a higher value. There’s also the inclusion of Digital pets such as CryptoKitties, a game that lets you collect and breed one-of-a-kind digital cats.

Importantly, as NFTs are being bought and sold in record numbers. There’s a high demand for secure, encrypted marketplaces and brokerages that allow buyers and sellers to view, commission and transact NFTs. This simply means that there are also opportunities for startups to become NFT brokers.

Royalties is also a passive way of generating income. The NFT Royalty is offered for the original creator of an NFTasset every time they are sold. The recursive selling will generate the royalty fees to the creator in the event of valuing their creation and innovation. For example, if an artist mints an NFT art and is listed in the marketplace, the artist will receive 10% from every sale.

All of these suggest opportunities which could be utilized by startups/entrepreneurs in the creative industry. While the future of any blockchain experiment is unknown. It has however been predicted that NFTs are here to stay and will continue to grow beyond the art and gaming realm, especially if wealthy investors continue to invest heavily in it.

Entrepreneurs in the creative industry and potential buyers are encouraged to invest in NFTs as they make their first step into a revolutionary future. We however advice that they seek professional advice to guide and protect their interests as they deal in it.

Omoruyi Edoigiawerie and Victor Adegbite

This article is published by Edoigiawerie & Company LP, a full service law firm offering bespoke legal services with a focus on startups, established businesses and upscale private clients in Nigeria. The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances. Our firm can be reached by email at hello@uyilaw.com .

Photo Credit: Aljazeera

by Legalnaija | Jan 13, 2022 | Uncategorized

The Legalnaija online bookstore is currently giving up to 50% sales on all orders for all books and references.

- A – Z Of Sports Law by Olisa Agbakoba Legal (₦2,500)

- A Force of Justice (A collection of law articles published in honour of Hon. Justice Oguntade JSC Rtd) (₦25,000)

- A Hand Book Of Criminal Law And Procedure Through Cases (Hard Cover) ₦10000

- Aviation Law An Practice In Nigeria by Ugo Ezeugwa (N13,500)

- Babalola’s Law Dictionary Of Judicially Defined Words And Phrases (2nd Edition)(₦5,000)

- Casebook On Data Protection(₦20,000)

- Casebook On Human Rights Litigation In Nigeria(₦20,000)

- Commercial Law And Practice by Eni Eja Alobo ₦9500

- Corporate Governance by Richard Adepeju & Felix Ojemhede Akahome (₦4000)

- Dark Hearts (Hard Cover) (₦4,500)

- Debt Recovery In Nigeria by Emeka Odikpo (₦3500)

- Entertainment Law In Nigeria by Michael Dugeri (₦24000)

- Hints On Land Doumentation And Litigation In Nigeria (Paperback) by Layi Babatunde SAN (N8500)

- Human Rights Litigation In Nigeria: Law, Practice And Procedure by Frank Agbedo (₦8,000)

- International Arbitration Law And Practice: The Practitioners Perspective by Tolu Aderemi (₦10,000)

- Journal Of Current Law And Arbitration Practice (Vol 1, No.2)(₦5,000)

- Law For The Layman (₦3,000)

- Law of Armed Conflict: Principles and Concepts by Hagler Okorie N4500

- Legal Research And Writing In Nigeria by Adewale Taiwo (N3250)

- Legal Rights And Obligations Under Nigerian Laws (Hard cover) (₦2500)

- Legal Rights And Obligations Under Nigerian Laws (Ebook) (₦900)

- LISTENEVERYHOW – How Negotiations Work by Jemide Ayuli ₦9000

- Metamorphosis; Tales By A Lawyer Girl by Adeola Osifeko ₦2800

- New Developments In Law And Practice In Nigeria(Essays In Honour Of Dele Adesina SAN) (₦20,000)

- Nigerian Conservation Law And International Environmental Treaties by Amari Omaka ₦8500

- Nigerian Energy Resources Law And Practice by Yemi Oke (₦9500).

- Principles Of Bail In Nigeria by Ekemini Udim (₦4900)

- Principles Of Clinical Ethics And Their Legal Dimensions In Nigeria (Paper Back) by Prof. Shima Gyoh and Layi Babatunde SAN ₦5000

- Privacy And Data Protection In Nigeria by Olumide Babalola (₦9500)

- Rights Of Suspects And Accused Persons Under Nigerian Criminal Law(₦6000)

- Social Media For Lawyers by Adedunmade Onibokun (₦1500)

- The Employment Law Handbook by Jamiu Akolade (₦15000)

- The Lawyer’s Companion – Paper Back by Layi Babatunde SAN (₦14500)

- The Nigerian Legal Method by Ese Malemi (₦4500)

- Tourism, Travels, Entertainment And Hospitality Law by Olufemi Abifarin (₦3000)

- The Nigerian Electricity Market; Understanding The Transactional, Legal & Policy Issues by Dr. Ayodele Oni (₦33,500)

- Understanding Petroleum (Oil & Gas) Transactions and the Nigerian Market by Dr. Ayodele Oni (₦50,000)

by Legalnaija | Jan 10, 2022 | Uncategorized

The Nigerian Bar Association classifies young lawyers as persons who have been called to the Nigerian Bar and qualified to practice law in Nigeria within the last seven years. Seniority at the Nigerian Bar is not dependent on the biological age of the lawyer, but rather on the years of legal experience which a lawyer has, commencing from the date of their call to the bar.

There is no Senior Advocate of Nigeria, Professor of Law, Justice of any court or legal scholar who did not begin their legal career as a young lawyer in Nigeria. Even persons who were long qualified to practice as legal practitioners in foreign jurisdictions before being called to the Nigerian Bar are also referred to as young lawyers in Nigeria for the first seven years from the date of their Call to the Nigerian Bar.

The Role of the Young Lawyer in the Litigation Firm

The role of the young lawyer in the Nigeriandispute resolution sector cannot be over-emphasized. Young Lawyers are the foot soldiers of almost every law firm and legal department in the country. They are engaged in almost every stage of the delivery of legal services to Clients. Their participation is direct and their impact is heavily felt. Even though young lawyers mostly work under strict supervision of their senior colleagues like infantry soldiers under the command of their superior officers, they are responsible for giving life to the policies and position of the firm.

Ideally, young lawyers are present during the briefing stage – when Clients narrate their problems or dish out instructions to the firm. They also engage in preliminary research of the clients’ problem and identify the legal issues involved in every problem. They also participate in the provision of actual solutions to the problems.

It is the practice of most litigations firms to leave the first draft of a writ or court process to the most junior (and inexperienced) lawyer. This junior lawyer who works on the first draft is largely responsible for selecting the legal issue(s) involved. By producing the first draft, the young lawyer inadvertently develops the skeleton and direction which the firm will take on that matter. Although the first draft is often reviewed and refined by a much older lawyer after close scrutiny, the young lawyer contributes to about 80% of the actual text of the final product.

After the final writ is produced, young lawyers often oversee the filing of the writ and follow up with procedural matters such as service and procuring hearing dates for the matter. Although some firms employ litigation clerks/assistants to handle these clerical roles, the reality is that most young lawyers in Nigeria also double as litigation clerks with these extra responsibilities.

The traditional role of the young lawyer extends to appearing in court for non-contentious matters, such as when the matter comes up for mention, or for hearing of simple applications i.e. for substituted service. Young lawyers are expected to build their experience by paying attention to other matters in court, especially when much senior lawyers are conducting their proceedings. Some young lawyers are lucky to have the good fortune of being allowed to handle trial or hearing of their substantive matters at an early stage in their career. Others have to be content with appearing together with the senior lawyers in their firms on the day of trial/hearing, until they receive a golden opportunity to handle their own trials/hearings.

Young Lawyers in the Appellate Courts: A Dangerous Experiment?

This position is usually the same at the appellate courts where the young lawyers are often tasked with preparation of the first draft of the notice of appeal and also the briefs of argument used at the appellate courts. This writer however questions the wisdom behind leaving critical matters on appeal to inexperienced young lawyers. The practice of allowing young lawyers have the first bite at an appellate cherry is not peculiar to only Nigeria, as it extends to other jurisdictions. An American legal author once decried this practice in the American courts when she wrote as follows:

“It is the trial of the most important case in your career, the case that you have been working on for years; and the most important witness on the other side has just finished direct testimony. The cross-examination is the moment you have been waiting for, the key, the pivotal part of the trial, the make-or-break of the entire case. And so, of course, you hand over the cross-examination to the most junior, the most inexperienced, the least knowledgeable lawyer on the team. Sound crazy? Of course it does. Yet, this –unfortunately – is a fairly description of what goes on in law firms across the country when it comes to appeals.”[1]

Undoubtedly, the resolution of disputes at the appellate courts is much different from litigation at the trial courts because while the fate of matters at trial courts depends largely on the advocacy of (senior) counsel during trial/hearing, the fate of a matter on appeal is almost wholly dependent on the quality of the briefs of argument filed. A critical examination of most judgments of the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court will show that the deciding justices pay only very little attention to the oral arguments made by counsel at the hearing. The briefs of argument are the prominent and significant feature of any appeal.

Admittedly, younger counsel need every experience they can get to sharpen their brief-writing skills. They need to be tutored extensively on the nitty-gritty of appellate brief writing and procedure in order to become well-versed in the process themselves. This experience is best gotten from close supervision by their senior colleagues and not merely by delegating the entire workload of development of the brief of argument to the younger counsel, which could prove to be very fatal in the long run as the inability to appreciate the crucial issues on appeal will almost definitely result in doom for that party.

Hence, it is advisable for experienced lawyers to dedicate their time to the development of briefs of argument filed in any appeal, in the same manner in which they dedicate their time to trials, rather than leaving the briefs to inexperienced younger counsel, without close supervision.

Declining Interest of Young Lawyers in Litigation

Given the crucial role of young lawyers in the litigation system as highlighted above, it is not far-fetched to submit that young lawyers are the fulcrum of the profession, in addition to being the future of the profession. A large part of the present burden of litigation practice is already being borne by young lawyers all over the country. However, many young lawyers engaged in litigation practice are not paid salaries commensurate to their workload and efforts.

There has been a declining interest in litigation by young lawyers all over the country in recent times as a result of the unattractive salary associated with young lawyers in litigation. The insalubrious delays associated with our court system has not helped matters. Young lawyers prefer to look at greener pastures in the corporate sector with its promise of exciting and highly rewarding practice areas.A great number of young lawyers in Nigeria are millennials who are naturally impatient and eager to reap quick rewards of their labour. They are largely uninterested in practices and ventures which do not yield immediate results.

Young Lawyers in Nigeria: Slaves v. Princes?

A young lawyer working in a tier 1 commercial law firmrecentlyresorted to social media to classify young lawyers working litigation firms “slaves” of the profession. He claimed that these lawyers aremostly sent to police stations to handle bail applications and to hot stuffy courtrooms to file and argue motions. These “slaves” are not deemed worthy of any further specialized training beyond what is taught at the law school, and are often remunerated with “peanuts”. This self-acclaimed classifier of lawyers contends that young lawyers practicing in the corporate field are the “princes” of the legal profession – mostly sent out for lofty board meetings and frequent professional trainings within and outside the country with fat salaries and bonuses to compensate their princely status.

Although this classificationof young lawyers is indeed disrespectful as it is divisive, it sadly reflects the “reality on ground”. Traditional employers of litigation lawyers are unwilling to sponsor or send their young lawyers out to attend quality professional trainings, but these same employers expect the young lawyers to operate with the passionate efficiency of the late ChiefGaniFawehinmi SAN and the intellectual sagacity of the late Niki Tobi JSC. It is indeed sad that some of these employers refuse to release the young lawyers in their firms to participate in even the free seminars organized by the Nigerian Bar Association and other professional bodies within and outside their immediate jurisdiction.

Elevating the Slaves to Princely Status

The legal market which provides legal services to clients thrives on the abundant supply of qualified practitioners available to clients. This supply of litigation lawyers is however under risk of decline, given the growing disinterest in litigation amongst young lawyers who rather favour more lucrative areas of law such as corporate commercial practice.

The decline in supply of dedicated young lawyers to the litigation practice sector will affect the quality of services rendered, as senior lawyers would be forced to handle a greater part of the work ordinarily done by young lawyers, which would affect quality of output produced by the firm.

Thus, it is necessary to address the crucial economic factors responsible for driving young lawyers away from litigation practice to ensure a renewed interest in this essential area of legal practice. This issue of remuneration of young lawyers was a deciding factor in the previous NBA national elections held in 2020, with many candidates promising to make it their primary concern. Some branches of the NBA have set up committees to look into the pressing issue of remuneration of young lawyers, and so many anonymous forms have been sent to young lawyers all over the country to collect the necessary information needed to combat the issue.

After his victory at the polls, the OlumideAkpata-led national administration of the NBA reportedly set up a committee to address the burning issue of the poor remuneration of young lawyers, in line with his specific promises which saw him emerge victorious at the national elections. There has however been a deafening silence from both the national headquarters of the NBA and the committee on this remuneration issue since the administration came on board and the stage is already being set for the next national elections…

Nonso Anyasi is a member of NBA Lagos Branch and can be reached via nonsoanyasi@nigerianbar.ng

[1] Nancy Wickelman, “Just a Brief Writer”, Westlaw 29 No. 4 Litigation 50 © 2003 American Bar Association, pg. 1.

by Legalnaija | Dec 9, 2021 | Uncategorized

Introduction

On the 4th of July 2021, The captain of the acclaimed biggest Nigerian professional football league (NPFL) club : Eyinmba united, Oladapo Augustine, got slapped with a one year ban for the use of a prohibited substance known as Prednisolone/Prednisone”. This was as a result of a test carried out on the player after his club CAF confederations league encounter against pyramids FC of Egypt. [1]

Also, in the buildup to the Tokyo 2020 Olympic games, 10 Nigerian athletes were declared ineligible to participate in the Tournament due to failure of a specific anti doping tests neccesitated by WADA which were not performed by the AFN. Those, being just a few of the several occasions that Nigerian athletes have been disqualified or stripped of their medals in various events due to their failure of anti doping tests despite the different measures taken by different sport regulating bodies to ensure strict compliance to the the rules of no doping.

Recently, one of Nigerian’s most decorated athlete, Blessing Okagbare, was banned from taking part in the semi finals of the Tokyo Olympics 100m race after it was found out that she had used a growth hormone in an out of competition test conducted earlier.

This article will attempt to perform an analysis of doping in Nigerian Sports, its possible effect on Nigerian Sports, causes and possible ways of ending this menace.

Doping : Definition and History.

According to Wikipedia, Doping is the use of banned athletic performance-enhancing drugs by athletic competitors[2]. The term is commonly used by organizations that regulate sporting competitions. FIFA defines it as a situation whereby players take “prohibited” substances to boost their performances. Prohibited substances in this context would mean steroids, cocaine, amphetamines or any substance that is on the World anti-doping agency (WADA) prohibited list.[3]

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) defines doping as “the intentional or unintentional use of prohibited substances and prohibited methods on the current doping list”.[4]

It will be interesting to note that even the use of natural supplements if found to contain such substances can constitute serious punishments for the player.

Doping is as early as the history of sport itself, Charles E. Yesalis states that :

“When humans compete against one another, either in war, in business, or in sport, the competitors, by definition, seek to achieve an advantage over their opponent. Frequently they use drugs and other substances to gain the upper hand. “[5]

The ancient Olympics in Greece had numerous forms of doping as athletes drank different herbal mixtures to gain more strength and give them more energy before chariot races. The prevalent use of drugs in sports possibly came due to the realization that athletes could achieve more using performance enhancing drugs than what is obtainable through hard work and rigorous training. It is also important to note that modern doping started after the world war when athletes began taking amphetamines to enhance their performances[6].

Hans-Gunnar Liljenwall, a Norwegian was the first Olympic athlete disqualified for doping. This was as a result of alcohol intake during the 1968 summer Mexico Olympics pentathlon. He was stripped of his medals and banned thereafter.[7] Russia was also recently banned from international sporting events for four years after they were found quilty of state sponsored doping by the world anti doping agency (WADA). Athletes will not be able to compete under the Russian flag in future competitions unless they do so under a neutral flag

Laws and regulations on anti doping.

Doping however is a phenomenon that should not be encouraged by anybody and any society as it violates the principles of fairness and healthy competition and also gives some athletes undue advantage over others and provides an unleveled playing ground for athletes. This exactly is what gave birth to the formation of the World anti doping agency(WADA).

World Anti Doping Agency(WADA) is the world body charged with the coordination of all anti doping activities at the international level. It conducts testings for all sports ranging from track and field competitions to ball games. It was established in 1999 and it’s activities are usually governed by a code known as the World Anti Doping Code.(WADC).

WADC is usually amended to ensure dynamism and to meet up with the growing development of pharmaceutical research in the world. It was launched in 2003 with the latest edition of WADC being that of 2021.

Article 1 of WADC specifically defines doping as the ” occurrence of one or more of the antidoping rule violations set forth in Article 2.1 through Article 2.11 of the Code.”[8]

This is followed up by Article 2 which corroborated what was laid out in article 1 by stating all the possible violations of the anti doping code and act that are punishable under the WADC by athletes. These includes :

* Presence of a Prohibited Substance or its Metabolites or Markers in an Athlete’s Sample.

* Use or Attempted Use by an athlete of a Prohibited substance or a prohibited method.

* Evading, Refusing or Failing to Submit to Sample collection by an Athlete.

* Whereabouts Failures by an Athlete.

* Tampering or Attempted Tampering with any Part of Doping Control by an Athlete or Other Person.

*Trafficking or Attempted Trafficking in any Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method by an Athlete or Other Persons.

* Administration or Attempted Administration by an Athlete or other Person to any Athlete In-Competition of any Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method, or Administration or Attempted Administration to any athlete Out-of-Competition of any Prohibited Substance or any Prohibited Method that is Prohibited Out-of-Competition.

* Complicity or Attempted Complicity by an Athlete or Other Person.

* Prohibited Association by an Athlete or Other Person.

* Acts by an Athlete or Other Person to Discourage or Retaliate Against Reporting to Authorities.

Article 3, 4 and 5 all speak about proof of doping, the WADA prohibited list which contains the list of all prohibited substances for sporting competitions and the process of investigation respectively.

Articles 9,10 and 11 give more insight to sanctions for these offences varying from bans and disqualification to removal of medals, see WADC 2021.[9]

Causes, Effects and Solutions.

Doping in Nigerian sport is not taken seriously due to the status of the country as a developing country. Anti doping laws are broken with impunity since there is no legal framework to punish offenders. This is not a favorable outlook for our national sports as the main basis on which sporting activities was founded upon will be destroyed. Hardwork and rigorous training to keep fit for competitions will be eliminated as athletes will end up using unethical methods to win.

Also when athletes are not properly checked for doping activities, they can cause themselves and their countries embarrassment if they eventually get caught by the anti doping agency regulating that competition. A good example of this is Lance Armstrong, A Former tour de France winner who got stripped of all his titles after he was found out to be using performance enhancing drugs to compete.

Furthermore, the health consequences of this act are not to be overlooked as there is high tendency for athletes to suffer hallucinations during and after games and in some instances death. An example is The death of Tom Simpson whose use of performance enhancing drugs pushed him into an overworked and dehydrated state and subsequently led to his death. Also despite it not being a direct cause of his death, drug abuse and doping might have been a cause of the death of late Soccer great Diego Maradona.

In order to check this growing menace in Nigerian sports it is imperative that a proper anti- doping agency should be created to handle all doping matters at local level. Also the need for awareness about doping and its consequences should be done because a lot of Nigerians lack basic knowledge about what constitutes doping and consequentially commit these offences in ignorance. for example the use of “paracetamol” before a sporting event by an athlete or player would be considered doping in saner climes. There should be proper education for athletes about the dangers of doping both to their physical and emotional wellbeing. NUGA, HIFI and other tertiary institution games organizers should employ the used of different methods of doping with serious punishments attached to those caught.

CONCLUSION

Nigeria as a country still has a long way to go concerning its anti doping regulations, however if the solutions outlined in this paper are duly followed, it will save the country a lot of embarrassment in international competitions such as the Olympics and FIFA world cups and also create a level playing ground for all Nigerian athletes. The creation of a functioning anti doping agency will be the first step in ensuring drug free competitions for Nigerian athletes nationally and internationally.

Omole damilare fisayo is a 200lvl law student of the faculty of law Adekunle Ajasin University Akungba Akoko Ondo state and a sport law enthusiast. He can be reached via

Omole damilare fisayo is a 200lvl law student of the faculty of law Adekunle Ajasin University Akungba Akoko Ondo state and a sport law enthusiast. He can be reached via

+2349020837174 or Omoledamilare093@gmail.com.

[1] Caf slams one year doping ban on eyimnba captain vanguardngr.com, July 27 2021

[2] Www.Wikipedia org, doping in sport.

[3]Anti doping- FIFA, https://www.fifa.com › legal › anti-d…

[4] Doping in football. Www.Goal.Com.

[5] History of doping in sport, Charles. E. Yesalis p 1

[6] Regulating doping in Nigerian sports, Ezza chigozie jude (LL. B (Hons),

[7] Doping in sport www.Wikipedia.org

[8] World anti doping code article 1

[9] Part one World anti doping code 2021

Babatunde Johnson is a law graduate from the University of Sierra Leone, Fourah Bay College and he is currently awaiting admission to the Sierra Leone Law School. He is also a legal content creator and Co- Founder at Salone Law Centre.

Babatunde Johnson is a law graduate from the University of Sierra Leone, Fourah Bay College and he is currently awaiting admission to the Sierra Leone Law School. He is also a legal content creator and Co- Founder at Salone Law Centre.

Omole damilare fisayo is a 200lvl law student of the faculty of law Adekunle Ajasin University Akungba Akoko Ondo state and a sport law enthusiast. He can be reached via

Omole damilare fisayo is a 200lvl law student of the faculty of law Adekunle Ajasin University Akungba Akoko Ondo state and a sport law enthusiast. He can be reached via