by Legalnaija | Feb 14, 2026 | Blawg, Uncategorized

The Faculty of Law, University of Lagos, has unveiled a newly renovated Law Annex Lecture Hall in honour of His Excellency, Justice George A. Oguntade, a retired Justice of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, in a ceremony that brought together eminent jurists, academics, legal practitioners, and government officials.

The event, held at the university’s Faculty of Law, highlighted the institution’s commitment to strengthening legal education and preserving the legacy of distinguished figures who have shaped Nigeria’s justice system. Leading the ceremony was the Dean of the Faculty of Law, Prof. Abiola Sanni, who described the renovation project as both a symbolic and practical investment in the future of legal scholarship.

Among the dignitaries present were the Chief Judge of Lagos State, Justice Kazeem Olanrewaju Alogba, the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Development Services), Prof. Foluso Ebun Lesi, who represented the Vice-Chancellor of the university, and Senior Advocates of Nigeria, Chief George M. Oguntade; Mrs Folashade Alli, Prof Lanre Fagbohun, Chief Bolaji Ayorinde and Prof Dayo Amokaye. Their presence underscored the significance of the occasion within both academic and judicial circles.

Speaking at the unveiling, speakers reflected on the remarkable contributions of Justice Oguntade to the Nigerian judiciary, legal jurisprudence, and mentorship of younger legal minds. The renovated facility, they noted, is designed to provide a more conducive learning environment for law students and to further enhance teaching and research activities within the faculty.

The ceremony also attracted senior legal scholars and public office holders, including Hon. Dayo Bush-Alebiosu, Commissioner for Waterfront Infrastructure Development in Lagos State, who is also one of the donors, Prof. Taiwo Osipitan SAN, and legal practitioner Mr. Olugbenga Ajala, Esq., who as the covener of the initiative spoke on behalf of the donors and whose attendance reinforced the strong collaboration between the legal profession and academic institutions in advancing legal education.

In his remarks, Justice Oguntade expressed appreciation for the honour bestowed on him, describing it as a profound recognition of his lifelong commitment to justice, integrity, and service. He urged students of law to pursue excellence and uphold ethical standards in their future careers, noting that the strength of the legal system depends largely on the character and diligence of those who serve within it.

The unveiling of the renovated Law Annex Lecture Hall marks another milestone in the Faculty of Law’s ongoing efforts to modernize its infrastructure and improve learning facilities. Stakeholders at the event emphasized that such initiatives not only preserve institutional heritage but also inspire the next generation of legal practitioners.

The ceremony concluded with a guided tour of the upgraded lecture hall and a renewed call for continued partnerships that will strengthen legal education and uphold the values of justice and rule of law in Nigeria.

by Legalnaija | Jan 4, 2026 | Uncategorized

They do say the law is an ass, but should it be so?

Can a trial court judge rewrite the law on rape sentence?

This girl’s name was Iruoghene Ogodo, an 11-year-old, and the Appellant was Mr. Afor Lucky, on 7th April 2012 he sent her to buy ‘pure water’ (sachet water) for him, thereafter he lured her into his room and forcibly had sex with her. An innocent child; bleeding from a torn hymen and injured vaginal wall, as confirmed by PW3 (the chief medical officer). a girl at that age can’t, in our criminal corpus juris, give consent, as ordained in section 30 of the Criminal Code and a similar provision in section 39 of the Penal Code.

Mr Lucky was charged and arraigned at the Delta State High Court on one count charge of rape under section 358 of the criminal code Law of Delta state, 2006. He didn’t deem it appropriate to plead guilty in order to expedite the proceeding, perhaps he felt he could get away with it. So he pleaded not guilty of course, like almost every defendant, and even raised alibi (claiming he wasn’t even there on 7th April 2012). Prosecution called Four Witnesses proving forceful penetration; PW3 satured the Virginal wall injury, ruling out other causes like bicycle riding as sheepishly claimed by the defendant to be a cause among the causes of virginal injury, he counter called two witnesses to establish his innocence. At this point, some questions are certainly inevitable. Would a trial judge, faced with such barbaric evidence against an 11-year-old, impose 5 years imprisonment with hard labor OR N300,000 fine? A girl that in law cannot give consent?After plea of allocutus, can mitigation rewrite life imprisonment under section 358 to 5 years imprisonment?

This is what happened in the case of LUCKY V. STATE (2016) 13 NWLR (Pt. 1528) 128.

The Delta State High Court, found him guilty as charged. After the plea of allocutus seeking for mitigation of his sentence, he was consequently given a sham sentence of 5 years with hard labour or N300,000 fine instead of life imprisonment. And the question was: does the trial judge actually rewrite the law? Because section 358 of the Criminal Code Law of Delta State, 2006, under which he was charged, provides for life imprisonment. What was his plea of allocutus about to warrant such mitigation? And if they were so compelling, can it be just to the victim and even de jure for them to be considered in such a magnitude offense? After all, justice is a three-way traffic.

Surprisingly, Mr Lucky protested, he was unhappy with even that leniency, and appeal to court of Appeal on 17th November 2014, the appeal was dismissed. The learned wise men called it ridiculous, however, they said their hands were tied since state didn’t cross-appeal, as such can’t temper with the sentence. Supreme Court in 2016 also affirmed the conviction; lamented the ‘contumacious violation’ of law, but resisted tampering with the sentence since no appeal was made against it by the state. Justices like Ngwuta, Okoro, Galadima JCS called it mockery, attack on justice, yet law is an ass.

I have read the case before, when I wrote my article titled: ‘Is the plea of Allocutus a right or a privilege in Nigerian criminal proceedings?’ but not meticulously like this. Upon reading it again today, I am not in total agreement with the decisions of the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court that they can’t temper with the sentence in the absence of the appeal. Can they really not invoke powers under sections 16 & 22 Court of Appeal Act and Supreme Court Act respectively to correct the error? I read the case over and over, erudite justices in pain, quoting Nafiu Rabiu v. State, but where then did they get the restraint from?On rape punishment? Section 358 provides: ‘any person who commits the offence of rape is liable to IMPRISONMENT FOR LIFE.’ No discretion, no option of fine.The above provision is clear and unambiguous, life for rape. In this case, where then did the trial court get 5 years from? Of course, I am not unaware of the position that pursuant to section 311 of ACJA (2015) Judges are enjoined to consider mitigating factors while sentencing, but can the said power be exercised in the offense of this magnitude considering even the circumstances of this case? Or should we safely say courts upheld an ass?

In my humble view, both the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court could have invoked their general powers pursuant to sections 16 and 22 of the Court of Appeal Act and Supreme Court Act respectively to correct the error. The sections respectively give them jurisdiction of the court of first instance; that’s to act as if the case was initiated or prosecuted before them to correct or amend, inter alia, errors; specifically this case being errors of law, awherend any other order the lower court could have made. This enormous power was given judicial recognition and duly applied in the celebrated case of Inakoju v. Adeleke (2007) 4 NWLR (Pt. 1025) 427, per Niki Tobi, JSC( as he then was) who delivered the lead judgment,affirmed the act of the trial court in granting reliefs sought in the substantive matter even though those reliefs were not part of the grounds of appeal before the Court. The case reached the Court of Appeal by way of an interlocutory appeal, solely to determine whether the trial court had jurisdiction to entertain the matter. Upon resolving that issue in the affirmative, the Court of Appeal refused to remit the case back to the trial court and proceeded to determine the substantive suit, relying on section 16 of the Court of Appeal Act. This approach was endorsed by Niki Tobi, JSC, and the majority of the Justices of the Supreme Court, with the exception of Oguntade, JSC,(As he then was) who dissented.

For emphasis, section 16 of the Court of Appeal Act provides as follows:

‘The Court of Appeal may, from time to time, MAKE ANY ORDER NECESSARY FOR DETERMINING THE REAL QUESTION IN CONTROVERSY in the appeal, and may AMEND ANY DEFECT OR ERROR in the record of appeal, and may DIRECT the court below to inquire into and certify its findings on any question which the Court of Appeal thinks fit to determine before final judgment in the appeal and may MAKE AN INTERIM ORDER or grant any injunction which the court below is authorised to make or grant and may DIRECT ANY NECESSARY INQUIRIES or accounts to be made or taken and GENERALLY SHALL HAVE FULL JURISDICTION OVER THE WHOLE PROCEEDINGS AS IF THE PROCEEDINGS HAD BEEN INSTITUTED IN THE COURT OF APPEAL AS COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE and may RE-HEAR THE CASE in whole or in part or may REMIT it to the court below for the purpose of such re-hearing or may GIVE SUCH OTHER DIRECTIONS as to the manner in which the court below shall deal with the case in accordance with the powers of that court, or, in the case of an appeal from the court below in that court’s appellate jurisdiction, ORDER THE CASE TO BE RE-HEARD by a court of competent jurisdiction.’[Capitalizations mine,for emphasis]

Section 22 of the Supreme Court Act contains similar and equally expansive provisions, empowering the Supreme Court to exercise the jurisdiction of a court of first instance where justice so demands. So no harm will be done if I refuse to qoute it.

Hey, you, yes you!Hold back your dagger, I am merely saying this in the light of the wordings of the sections and the judicial pronouncement. I hope I am right. It wouldn’t be terrible even if I am wrong, but I believe the courts could have fallen back to the provisions to ensure the ungodly and ungrateful perpetrator of the heinous act faces the wrath of the law accordingly. And on that; I say no more.

Isah Bala Garba is a level 300 student from Faculty of Law, Bayero University, Kano. He can be reached for comments or corrections on: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/isah-bala-garba-301983276 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/isah.bala.garba

isahbalagarba05@gmail.com or on 08100129131

by Legalnaija | Dec 5, 2025 | Uncategorized

The Practical Training Academy Ltd/Gte (TPTA) Delivers Comprehensive Public Law Office Training for Cross River State Ministry of Justice

Five-day bespoke programme enhances capacity of 143 legal professionals

The Practical Training Academy Ltd/Gte (TPTA) and The Law Crest LLP, in collaboration with the Cross River State Ministry of Justice, successfully delivered a specialised five-day training programme for public sector legal practitioners between 1st and 5th December 2025.

The intensive training, attended by 143 staff members of the Cross River State Ministry of Justice, was designed to strengthen capacity in public sector legal practice through a combination of presentations, workshops, and practical sessions. The programme received highly positive feedback from participants throughout its duration.

The training manual was developed through a collaborative effort between the progressive and dynamic Honourable Attorney General of Cross River State , Mr Ededem Ani Esq and his team, working alongside TPTA’s team, led by Mr Tobenna Erojikwe. This partnership ensured the content was tailored to address the specific needs and context of public legal work in Cross River State.

The programme featured a structured approach beginning with foundational sessions on the structure and functions of public legal work, before progressing to more specialised areas including public sector lawyering, international best practices, and technology-enhanced legal office management.

Participants engaged with in-depth sessions covering criminal procedure, data protection, contract law, procurement processes, public-private partnership frameworks, civil litigation strategy, legislative drafting, taxation principles, and administrative law. Each session was designed to provide both theoretical understanding and practical application relevant to public sector legal practice.

The training drew upon the expertise of distinguished practitioners from both the United Kingdom and Nigeria, including:

– Sheila Saunders, Director-level UK public sector lawyer

– Prof Paul Idornijie SAN

– Victor Opara SAN

– Tola Oshobi SAN

– Folabi Kuti SAN

– Saheed Adebisi Quadri

– Tobenna Erojikwe

– Professor Danwanka Shuaibu

– Dr Jude Odinkonigbo

– Rotimi Ogunyemi

– Oluchi Uchegbu

– Olatunji Muritala

– Ayomide Oduyela

This collaboration between The Practical Training Academy and the Cross River State Ministry of Justice represents a significant investment in enhancing the quality and effectiveness of public sector legal services in Cross River State.

Participants at the training will earn 5 NBA-ICLE points.

TPTA is a not for profit company founded by Tobenna Erojikwe to provide career development opportunities through trainings, mentorship’s and other skills acquisition and professional development initiatives. It has entered into strategic partnerships with individuals, notable international and local law firms, corporates and institutions involved in career development for the advancement of its objectives.

TPTA was launched in September 2025 and has delivered 12 free NBA-ICLE accredit training sessions in 3 key thematic areas. Its YouTube Channel @thepracticaltrainingacademy has had over 24,000 views with over 3,000 subscribers.

by Legalnaija | Dec 3, 2025 | Uncategorized

INTRODUCTION:

The power of prosecution is constitutionally vested in the Attorney-General of the Federation and the Attorney-General of each state, but it can also be exercised by other agencies and individuals like the police and private legal practitioners, subject to the Attorney-General’s authority. This power involves the discretion to commence, continue, or discontinue any criminal proceeding, which must be exercised fairly, independently, and in the public interest, the Attorney-General holds the ultimate power to prosecute, discontinue, or take over any criminal case. The Attorney-General can delegate this authority to other officers within their ministry or to legal practitioners.The police and other bodies can also prosecute cases, but this power is subordinate to the Attorney-General’s overriding authority and must be exercised within legal boundaries, while the police have prosecutorial powers, they are subject to the Attorney-General’s control, for higher courts, police officers must be qualified legal practitioners. Prosecutors have broad discretion, including the power to choose the charge, decide whether to prosecute or not, and pursue plea bargains. The exercise of prosecutorial power is subject to judicial review to ensure fairness and adherence to the rule of law, a prosecutor must consider the public interest when deciding whether to prosecute, even if there is sufficient evidence of a crime. References to the case of Akpa V. State (2008)LPELR-368(SC)

Brief Fact of the case contain as follows:

The case of the prosecution is that the deceased, Ikechukwu Njoku, visited the appellant at Jibia and never returned. He was murdered by the appellant. At the scene of crime, police recovered a human body without legs, arms and neck. In the inner room of the appellant’s shop, police found the floor of the room and a mattress soaked with blood. They also found blood stain by the hole of the pit latrine attached to the inner room. When the pit latrine was dug open they saw two human legs. Appellant was arrested for murdering Ikechukwu Njoku on or about 3rd of December, 1989. The learned trial Judge found the appellant guilty of culpable homicide punishable with death and sentenced him to death. His appeal to the Court of Appeal was dismissed, further appeal to the Supreme Court.

ANALYSIS vis a vis DECISION OF THE CASE:

The Supreme Court, per NIKI TOBI, J.S.C. (Delivering the Leading Judgment), upheld both the judgment of trial and lower courts by dismissing the appeal of the appellant emphasizing on the power of the Prosecution to prosecute vis a vis power of the court to prosecute a person, the court held that the prosecution has an unfettered discretion to prosecute persons in Court because the discretion is unfettered, Courts of law do not have the power to question it. The only jurisdiction of the Court is to try accused persons presented before it for prosecution. A Court cannot go outside the prosecution and ask for some other person to be charged before it.

The mere fact that an accused person specifically mentioned other persons in his statement to the police in the chain of criminality or criminal liability does not necessarily mean that the persons are in fact guilty of the offence or must as a matter of law be charged to Court. And what is more, I know of no law which says that because other persons who committed an offence are not charged to Court, the accused person charged to Court must, on that ground, be discharged and acquitted. Criminal liability is personal. It cannot be transferred. This is because the mens rea or actus reus is on the accused in Court and cannot be transferred to any other person not charged. By way of recapitulation, I should say that the prosecution is not under any regimental duty or any duty at all, to charge all possible accused persons. I should perhaps mention here the practice where the prosecution, instead of charging a particular suspect, decides to call him as a witness, to ensure the conviction of a particular accused person or particular accused persons.

However, in other hand their are circumstances in which the order of mandamus is directed to an individual, body, tribunal or inferior court requiring the performance of some specified thing in the nature of a public duty appertaining to his office. The performance of the duty need not involve a judicial function.” References to the famous case of Fawehenmi V. Halilu Akilu (1987) SC

Brief fact of the case of Fawehenmi V. Halilu Akilu (supra)

This is an appeal against the judgment of the Court of Appeal. The facts of this case was that on Sunday, the 19th October 1986, Mr. Dele Giwa, a Journalist and Editor-In-Chief of a weekly magazine, NEWSWATCH, was killed in his residence at Ikeja in Lagos State by a parcel bomb. On the 3rd of November, 1986, the Appellant, a friend and legal adviser to Mr. Dele Giwa (deceased) submitted to the respondent a 39 page documentation containing all details of the investigation he conducted together with an information accusing two army officers of the murder of Dele Giwa. The two army officers are: Col. Halilu Akilu, the Director of Military Intelligence and Lt. Col. A.K. Togun, Deputy Director of the State Security Service. Pursuant to Section 342 of the Criminal Procedure Law of Lagos State, the applicant acting as a private prosecutor requested the Respondent as Director of Public Prosecutions, Lagos State to exercise his discretion whether or not, he would prosecute Col. Akilu and Lt. Col. A.K. Togun for the murder of Mr. Dele Giwa and if he declines to prosecute, to endorse a certificate to that effect on the information submitted to him by the applicant/Appellant. This is to enable the applicant/Appellant to prosecute Col. Halilu Akilu and Lt. Col. A.K. Togun for the murder.

Subsequently, the Appellant met the Respondent in the Respondent’s office, as he could not meet the Respondent on Wednesday the 5th of November 1986. The Respondent informed him that he could not come to a decision whether or not to prosecute Col Halilu Akilu and Lt.Col A.K. Togun for the murder of Mr. Dele Giwa until he received a Police Report of Police Investigation. The Appellant filed an application in the High Court of Lagos State for leave to apply for an Order of Mandamus to compel the Respondent to decide whether or not to prosecute these two accused persons and if he decides not to prosecute, to endorse the information that he has seen the information but he had decided not to prosecute at public instance. The learned trial Judge dismissed the application. The Appellant appealed to the Court of Appeal which dismissed his Appeal on the ground that the Appellant has no Locus Standi in the death of Dele Giwa to bring the Application he has brought. Secondly, the Court of Appeal held that the Chief Judge of Lagos State was right in refusing appellant’s leave on the limited materials before him. The two Courts i.e. the High Court and the Court of Appeal held that the Appellant’s application was hopeless. frivolous, improper, ill-timed, hasty and pre-mature. The Appellant appealed to the Supreme Court against the decision of the Court of Appeal.

From the above fact of this case it’s extremely clear that where prosecution failure to prosecute a person, a court of law can compel the prosecution for a specific performance in other to grant an individual or private individual power of fiat to prosecute such matter by way of applying or seeking the leave of the court to grant an order of mandamus.

ANALYSIS vis a vis DECISION OF THE CASE OF FAWEHENMI V HALILU AKILU (supra)

ANDREWS OTUTU OBASEKI, J.S.C.(Delivering the Leading Judgement): This appeal raises two important questions which will continue to be debated in legal circles for a long time. The 1st question touches the locus standi of the appellant to initiate and institute these proceedings in the High Court. In other words, has the appellant established his locus standi entitling him to seek leave of the High Court to apply for an order of mandamus? The second question concerns the quantum or sufficiency of the facts deposed to and placed before the High Court in an application of this sort.

The law has being settled by vesting power on the Attorney-General to grant a fiat to an individual who so wish to prosecute their case personally, failure of the Attorney-General to grant such fiat will avail such an individual to seek the leave of the court for an order of mandamus to enable personal prosecution (individual) have the locus standi in which the court can compel a body or public prosecution to appertaining it office responsibility. References to CBN V. SYSTEM APPLICATION PRODUCTS (NIG) LTD (2004) LPELR-5432(CA)

The order of mandamus requested by a party is among the prerogative orders which are discretionary common law remedies which a High Court may grant in the exercise of its supervisory jurisdiction over the proceedings and decisions of inferior Courts and Tribunal and control of governmental duties and powers. It is a public law remedy and is directed against officers in their capacity as such or against public bodies such as the CBN, A.G PSC and other government parastatals. It aims at compelling the performance of a public duty in which the person applying for it has sufficient legal interest. In the case of Shitta-Bay v. Federal Public Service Commission (1981) 1 SC 40, cited by the learned trial Judge, Idigbe, JSC, said – “The order of mandamus, of course, only issues to a person or corporation, requiring him or them to do same particular thing therein specified, which appertains to his or their office, and is in the nature of a public duty.” The case of the Queen v. Western Urhobo Rating Authority and Ors Ex-Parte Odje and Ors (1961) All NLR 796, a public duty to do the act in question, has been held to be one that must be imposed upon the person against whom the order is sought. In Fawehinmi v. Akilu (1987) 4 NWLR (Pt. 67) 797, it was held that the proposed recipient of an order of mandamus must be an individual body, or Tribunal, or Inferior Court with a public duty to the applicant. And, finally, such public duty need not to be imposed by statute only. It may be a duty under the common law, and even duty under customary law is enforceable by an order of mandamus. See: Layanju v. Araoye (1961) 1 All NLR 83, (1959) 4 FSC 154 at 157; The Queen (Ex-Parte Ekpenga v. Ozogula II (1962) 1 All NLR 796. It must be noted however that the person enjoined to perform the act must have failed upon demand to do it. See R v. I.R.C. (1962) 1 SCNLR 423; Re-Nathan (1884) 12 QBD 461.” Per IBRAHIM TANKO MUHAMMAD, JCA (Pp 21 – 23 Paras F – C)

In light of the above the prosecution has power to prosecute and tender evidence/exhibits in other for the court to convict the defendant, the defendant can only be convicted where the prosecution have established a prima facie case by linking the act of the defendant to the crime alleged to have being committed or after the close of prosecution case and the defendant file a No Case Submission and it has being overruled by the court and failure of defendant to open a defense in an allegation of criminal offence against him in this circumstances the defendant is exposing himself to risk and gambling that may warrant or land him to have committed such offence before a court of law. References to the case of Adamu V. State (2014)LPELR-22696 (SC), Ejibade V State (2012)LPELR-15531 (SC). Unreported case of Federal Republic of Nigeria V. Nnamdi Kanu FHC/ABJ/CR/383/2015

Attorney-General’s Constitutional Power

The power to prosecute is established in Nigeria’s Constitution 1999 as amended. Section 174 grants this power to the Attorney-General of the Federation, and Section 211 grants it to the Attorneys-General of the states.

(a) This authority includes the power to commence, continue, and discontinue any criminal proceedings.

(b) The Attorney-General can exercise this power personally or through officers in their ministry or department.

Delegation and Limitations

(a) The Attorney-General can authorize others to prosecute, such as the police or other legal practitioners.

(b) The police have a statutory role in prosecution but are ultimately subject to the Attorney-General’s overriding authority.

(c) While private citizens can be empowered by law to lay a complaint, they cannot prosecute that complaint in court without the Attorney-General’s explicit authorization or “fiat”.

Discretionary Power

(a) The Attorney-General has broad discretion in exercising this power.

(b)This discretion can be used to decide which charges to file and what plea deals to offer, potentially impacting the outcome of a case.

(c) The Attorney-General has discretion include the power to enter a nolle prosequi, which discontinues a prosecution without a formal acquittal.

From the above analysis it’s obvious that both parties, that the Attorney General of either a State or the Federation has unfettered discretion power to either prosecute or discontinue prosecution of a criminal case against any person. The discretion of the Attorney General can be exercised by him in person or through officers of his department and once the power or discretion has been properly exercised no one can question it, including the Courts. See Section 174 (1) – (3) and Section 211 (1) – (3) of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), references to the following cases: AUDU V. A.G. FED. (2013) 8 NWLR (Pt. 1355) 175, STATE V. ILORI & 2 ORS. (1983) 2 SC 155, ALHAJI ATTA V. C.O.P. (2003)5 F.R. 186, SHIDALI V. F.R.N. (2008) ALL FWLR (Pt. 421) 899, ABACHA V. STATE (2002) 11 NSCQR 345 at 381, FRN V. OSAHON (2006)25 NSCQR 512.” Per ADAMU JAURO, JCA (Pp 12 – 12 Paras A – E)

The Supreme Court of Nigeria in the famous case of STATE V. ISIJOLA (2023) LPELR-59935(SC), Per MOHAMMED LAWAL GARBA, JSC (Pp 15 – 16 Paras D – A) In a dissenting opinion that:

“Whether a person can be tried by a High Court where no charge has been filed/preferred against him“

“Section 185 (b) of the CPC, Cap 35, Laws of Niger State of Nigeria (Revised Edition) 1989 pursuant to which the application was made and granted, simply provides that: “185. No person shall be tried by the High Court unless:- (b) a charge is prepared against him without the holding of a preliminary inquiry by leave of a Judge of the High Court.” Briefly, these provisions prescribe that the trial High Court shall not try any person unless a charge is preferred or filed against him in that Court with the leave of a Judge thereof.”

It’s from the above judicial authority which this article center on which I also derive my opinion that their is no any court of law in Nigeria that can either compel the prosecution neither the court itself prosecute a person without no any charge filed/preferred against a person before a court of law as such any party who front load an originating process seeking an order of mandamus or certiorari to compel the prosecution to prosecute a person which is not initiatiated by the prosecution itself such matter instituted against prosecution is dead on arrival, because the choice of who to prosecute is exclusively that of prosecution. References to the case of GOLIT V. IGP (2018) LPELR-46188(CA).

Furthermore, “the law is now fully settled that a Court cannot interfere with the prosecutor’s right to file a charge nor can it prevent the EFCC from initiating a charge or information against any person in the Federal High Court, High Court of a State or the FCT High Court once the matter or criminal proceedings has to do with economic or financial crimes and there is a law in place whether under Act of National Assembly or law of a state for instance criminal code law or Penal Code Law criminalizing the crimes or offences for which the Defendant is arraigned or charged within a State High Court. References to the famous case of ALIYU V. F.R.N. & ORS (2020) LPELR-50517(CA) and also see ISIAKA MUMINI V. FRN (2018) 11 SCM 127 at 137 – 138 A – B per EKO JSC who said: “I think it has to be borne in mind that the choice of the charge to prefer against the accused person on a given set of facts is the prerogative of the prosecutor. Neither the Court nor the accused person can interfere with the prerogative of the prosecutor in this regard. From a line of cases, including Yongo V. Commissioner of Police (1992) 8 NWLR (Pt. 257) 36; Alake V. The State (1992) 9 NWLR (Pt. 265) 260: Chima Ijioffor V. The State (2001) 4 SC (pt. 11) 1; (2001) NWLR (Pt. 718) 371, the Courts recognize and respect this prerogative of the prosecutor to prefer any charge from the facts at his disposal. Thus as Achike, JSC, Stated in IJIOFFOR V. THE STATE (supra) the prosecutor’s – Prosecutorial responsibility is to establish his case beyond reasonable doubt in order to secure the conviction of the (accused person). How he gets about discharging this is entirely his business. Under no circumstance will the accused person dictate to the prosecution what charge shall be preferred or what witnesses shall be fielded against him in discharge of the prosecutor’s prosecutorial responsibilities.” Per PETER OLABISI IGE, JCA (Pp 46 – 47 Paras D – F)

Conclusion:

The law is clear that the power of prosecution is constitutionally vested on the Attorney General of the Federation and the Attorneys General of the states, who have the authority to institute, continue, or discontinue criminal proceedings. Other bodies, such as the police, can also prosecute, but their power is subordinate to the Attorney General’s authority and is subject to limitations or restrictions by the Attorney General. Other laws may grant specific agencies concurrent prosecution powers for particular offenses and a particular individual can also prosecute by authorization of fiat.

However, the jurisdiction of a court of law is to entertain criminal proceedings initiated by the prosecution which is apparent in our legal system, court does not in anyway inherit any power to either to compel the prosecution to discharge it duty statutory vested on prosecution though in some circumstances the court can compel the prosecution to grant a fiat to an individual to prosecute their case nor the court doesn’t has power to prosecute a person.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Full Name: MOHAMMED YAHAYA PICHIKO

Email:pichiko321@gmail.com

Number: 07033412386

Hobbies: READING & RESEARCH

Current Positions: DIRECTOR FOR MOOT & MOCK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF NIGER STATE LAW STUDENTS’ (NANIGLAWS NHQ) AND CURRENT JUDGE 3 UNION COURT BUK.

by Legalnaija | Oct 27, 2025 | Uncategorized

From iPhone XR to iPhone 17 Pro Max: Innovation or Infringement? The Intellectual Property and Legal Reality of Unauthorized Conversions

Introduction

In recent months, the internet has been flooded with videos and offers showing how an iPhone XR can be “converted” or “upgraded” into the latest iPhone 17 Pro Max—often through software modifications and hardware tweaks. Many of these offers claim to source devices directly from China at a low cost, supposedly helping consumers avoid what they describe as “extortion” from retailers in Nigeria and other countries.

While this trend might seem attractive to consumers seeking the prestige of owning the latest iPhone model without spending millions of naira, the legal implications are far-reaching. Beyond the economic effects on Apple and legitimate retailers, there are serious intellectual property (IP) and consumer protection concerns that must be examined.

This article explores these issues through the lens of Intellectual Property Law—highlighting how such conversions may amount to multiple forms of IP infringement under Nigerian, U.S., Chinese, and international (WIPO) law.

Understanding Intellectual Property Protection in iPhone 17 Pro Max

Intellectual Property Law exists primarily to protect the economic and moral rights of creators and innovators. Apple Inc. is one of the world’s most active IP holders, securing comprehensive protection for every new product before launch.

The iPhone 17 Pro Max is protected under several categories of IP:

- Trademark Protection

Apple’s trademarks protect identifiers such as:

a. The name “iPhone”, “iPhone 17 Pro Max”, and Apple’s bitten apple logo.

b. Taglines such as “Ceramic Shield” or “Fusion Camera”.

These are registered marks globally under the Madrid Protocol (administered by WIPO), and also locally in the United States, China, and Nigeria (under the Trademarks Act, Cap T13, LFN 2004).

- Copyright Protection

Apple’s iOS 18/19/26 operating system, interface icons, sounds, animations, and even wallpapers are protected under copyright law as original literary and artistic works.

Reproducing or modifying these without authorization violates:

a. Section 15 of the Nigerian Copyright Act 2022,

b. Title 17 of the U.S. Code (Copyright Act), and

c. China’s Copyright Law (2020 Amendment).

- Industrial Design Rights

The shape, finish, and camera layout (“camera plateau”) of the iPhone 17 Pro Max are protected by industrial design rights, covering the non-functional aesthetic features.

Under Part II of the Nigerian Patents and Designs Act, and China’s Patent Law (Design Patent provisions), copying these features without permission constitutes design infringement.

Apple’s proprietary technologies—such as the A19 Pro chip architecture, camera sensors, and image processing pipelines—are likely covered by utility patents. These patents prevent unauthorized use, reproduction, or reverse-engineering of Apple’s technology.

4. Trade Secrets

Apple also protects certain confidential elements—such as camera algorithms, optical systems, and noise-reduction software—under trade secret laws, notably under the U.S. Defend Trade Secrets Act (2016) and similar provisions in Chinese law.

Together, these protections form a comprehensive IP fortress safeguarding Apple’s innovation and commercial interest globally.

The Conversion Practice: iPhone XR to iPhone 17 Pro Max

The “conversion” process typically involves modifying an iPhone XR to mimic the look, software interface, and branding of the iPhone 17 Pro Max. This can include:

- Installing unauthorized firmware versions mimicking iOS 26,

- Physically altering the casing to resemble the newer model,

- Rebranding or remarketing the phone under Apple’s trademarked name.

Legal Implications

This practice is not a harmless customization. It constitutes IP infringement under multiple grounds:

- Trademark Infringement: Rebranding a device as “iPhone 17 Pro Max” without authorization misleads consumers and dilutes Apple’s brand identity. This is a violation of Section 5 of Nigeria’s Trademarks Act, Lanham Act (U.S.), and Article 57 of China’s Trademark Law.

- Copyright Infringement: Installing or distributing modified Apple firmware (unauthorized iOS versions) breaches Apple’s copyright and software license agreements.

- Industrial Design & Patent Violation:

Copying the iPhone 17 design or hardware configurations violates Apple’s industrial design and patent rights, particularly when done commercially.

- Trade Secret Misuse: If the conversion uses or discloses confidential Apple schematics or software reverse-engineering, it may also breach trade secret protection under international law.

Applicable Legal Frameworks

- International Law (WIPO)

Apple’s IP rights are enforceable globally through the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

Under:

- The Paris Convention (1883) for industrial property,

- The Berne Convention (1886) for copyright, and

- The TRIPS Agreement (1994) under the WTO,

member countries—including Nigeria, China, and the United States—must protect Apple’s IP rights within their jurisdictions.

- Nigerian Law

- Copyright Act 2022 (Sections 27–32): prohibits unauthorized reproduction, distribution, or adaptation of copyrighted works.

- Trademarks Act (Cap T13, LFN 2004): criminalizes unauthorized use of registered marks.

- Patents and Designs Act: protects industrial design and invention originality.

Violations can attract civil liability (damages, injunctions) and criminal penalties, including imprisonment and fines.

- U.S. Law

Apple’s home jurisdiction provides strong remedies under:

- Title 17 USC (Copyright Act),

- Lanham Act (Trademark Law), and

- Patent Act (35 U.S.C.).

Apple frequently sues counterfeiters and modifiers under these provisions.

- Chinese Law

Although much of this conversion originates in China, Chinese IP Law (2020–2021 revisions) imposes strict penalties for:

- Counterfeiting registered trademarks,

- Manufacturing or exporting infringing products,

- Reverse-engineering patented technology.

China, as a WIPO member, enforces these under the State Intellectual Property Office (CNIPA).

Liability Analysis

- The Company Converting the iPhone XR

Such a company directly infringes Apple’s IP by:

- Using Apple’s registered marks without authorization,

- Modifying firmware (copyrighted work),

- Copying design and technical components (industrial design & patent infringement).

Under Nigerian law and WIPO conventions, this is an actionable civil and criminal offense.

- Individuals Marketing the Converted Devices

Promoting or selling converted devices constitutes secondary infringement or aiding and abetting infringement.

Even advertising these products can violate Section 36 of Nigeria’s Copyright Act and Article 57 of China’s Trademark Law.

- End Users

Although end users may not be prosecuted criminally, knowingly purchasing counterfeit or converted devices could lead to:

- Loss of warranty and data protection,

- Exposure to unsafe and non-compliant devices, and

- Civil forfeiture if proven as willful participation in IP infringement.

What Should Be Done

- Enforcement and Regulation

Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC), Trademarks, Patents, and Designs Registry, and Standards Organisation of Nigeria (SON) should collaborate to identify and restrict the importation or sale of such converted products.

- Apple Inc. can initiate cease and desist notices, border measures, and civil suits.

- Awareness and Education

IP practitioners, regulators, and the public must be educated on the economic and legal consequences of supporting counterfeit conversions.

Consumers need to know that authenticity and innovation are core values of IP protection.

- Collaboration Between Jurisdictions

Since many of these conversions originate from China, bilateral cooperation between Nigeria Customs Service and Chinese IP enforcement agencies (CNIPA) is vital to curb illegal exports.

Conclusion

While converting an iPhone XR into an iPhone 17 Pro Max may appear innovative or cost-saving, it raises serious intellectual property violations and economic concerns.

Each iPhone model embodies years of research, design, and technological development protected by international IP laws.

By altering or misrepresenting Apple’s products, these conversion companies undermine the integrity of IP systems, distort the market, and erode trust in legitimate innovation.

The law is clear, unauthorized reproduction, modification, or branding of protected technology is illegal under Nigerian, U.S., Chinese, and WIPO frameworks.

Consumers, creators, and regulators must all play their part in protecting intellectual property—because the true value of innovation lies not in imitation, but in originality.

by Legalnaija | Oct 15, 2025 | Uncategorized

Introduction

Defamation remains one of the most sensitive aspects of Nigerian law, a space where personal reputation and freedom of expression constantly meet and sometimes collide. The law recognizes that while every person is entitled to protect his or her good name, society must also preserve the freedom to speak the truth, express honest opinion, and hold others accountable. It is against this background that both civil and criminal defamation have developed under Nigerian law, each with distinct purposes and procedures.

Understanding Civil and Criminal Defamation

Civil defamation arises under the common law of tort and is designed to compensate a person whose reputation has been unjustly damaged by another’s false statement. Criminal defamation, on the other hand, is a statutory offence under Sections 373–381 of the Criminal Code Act (applicable in Southern Nigeria) and Sections 391–395 of the Penal Code (applicable in Northern Nigeria). Its aim is to protect public peace and order by punishing statements capable of provoking violence or widespread hatred.

The Court of Appeal in Okotcha v. Inspector-General of Police (2019) LPELR-47848 (CA) explained that civil defamation is concerned with personal injury to reputation, while criminal defamation concerns the peace of the public. The dividing line, therefore, lies in the intention behind the publication and its likely effect on society. A publication that merely injures an individual’s reputation is civil, but one that tends to incite public disorder or hatred crosses into the criminal sphere.

In both civil and criminal defamation, the parties and the remedies sought differ fundamentally in purpose and consequence. In civil defamation, the action is a private one between the plaintiff, whose reputation has been injured, and the defendant, who made or published the defamatory statement. The remedy here is primarily compensatory damages, injunctions, or an apology to restore the injured person’s reputation. In contrast, criminal defamation is a public prosecution instituted by the State through the police or the Attorney-General against the accused person for an offence that threatens public order. The remedy in this case is punitive, involving fines or imprisonment as provided under the Criminal and Penal Codes. As the Court of Appeal held in Okotcha v. I.G.P. (Supra). The accused person here, enjoys the shade of constitutional safeguards of Presumption of innocence as guaranteed under Section 36(5) of the 1999 Constitution, and failure to establish any of the fundamental ingredients of offence alleged will occassion into failure of the charge and will lead to the discharge of the defendant.

Improper Invocation of Police Powers

It has become increasingly common to see individuals rushing to the police over issues that are clearly civil in nature, including defamation. Such practices have no basis in law. The Police Act, 2020, in Section 4, clearly defines the duties of the Nigerian Police Force as:

“The prevention and detection of crime, the apprehension of offenders, the preservation of law and order, the protection of life and property, and the due enforcement of all laws and regulations.”

Nowhere in the Act is the police empowered to intervene in purely civil disputes or to enforce personal rights. In Onagoruwa v. State (1991) 5 NWLR (Pt. 193) 593, the Court of Appeal described the police in words that still echo today:

“They are custodians of legality, not instruments of oppression. Their duty is to enforce the law, not to manufacture offences where none exist.”

When the police act outside these limits, they act ultra vires, beyond their lawful authority. Any proceeding or prosecution founded on such misuse is void. Moreover, such conduct wastes the court’s precious time and erodes public trust in both the law and its institutions. Courts have consistently warned against the abuse of their process, as seen in A.G. Anambra State v. Okeke (2002) 12 NWLR (Pt. 782) 575, where the Supreme Court cautioned that the judicial process must never be used as a tool for harassment or revenge.

Ingredients of Defamation

For civil defamation, the claimant must prove three essential elements:

- That the statement complained of is defamatory;

- That it refers to the claimant; and

- That it was published to a third party.

For criminal defamation, the prosecution must go further to prove beyond reasonable doubt that:

- The accused published defamatory matter;

- The publication referred to the complainant;

- It was false;

- It was made with intent to harm the complainant’s reputation; and

- It was not protected by any lawful defence or privilege.

These requirements underscore the seriousness with which the law views defamation, especially when it borders on criminal conduct.

Defences to Defamation

The law is not blind to the need for fairness. It recognizes that people should not be punished for speaking the truth, expressing honest opinions, or communicating in good faith. The defences available to a person accused of defamation ensure that justice does not silence legitimate expression.

Defences in Civil Defamation

- Justification (Truth)

The truth of a statement is an absolute defence. No one has the right to complain about a statement that is substantially true. In Oruwari v. Osler (2013) 5 NWLR (Pt. 1348) 535, the Court of Appeal held that “truth is a complete defence to defamation, for the law does not protect a man from the publication of that which is true about him.”

- Fair Comment on Matters of Public Interest

A person may freely express an honest opinion on a matter of public importance, provided it is based on facts that are true and expressed without malice. The Court of Appeal in Sketch Publishing Co. Ltd v. Ajagbemokeferi (1989) 1 NWLR (Pt. 100) 678 held that fair comment must be an opinion any reasonable person could hold, not a reckless assertion.

- Qualified Privilege

Certain communications made in the performance of a duty or in the protection of a legitimate interest are privileged. This defence will fail only where malice is proved. In Emeagwara v. Star Printing & Publishing Co. Ltd (2000) 14 NWLR (Pt. 688) 372, the court affirmed that a statement made in good faith, in discharge of a duty, is privileged.

- Absolute Privilege

Some occasions are so vital that the law gives complete immunity from liability, even if the words are false or malicious. Examples include statements made in judicial proceedings, legislative debates, or official acts performed in the line of duty. The case of R v. Governor of Lagos, Ex parte Roderick (1970) NMLR 204 recognized this principle.

- Innocent Dissemination

Those who unknowingly distribute defamatory material such as printers, booksellers, or internet service providers are protected where they had no reason to suspect the material was defamatory. The English case of Byrne v. Deane (1937) 1 KB 818, which has been followed in Nigerian courts, illustrates this principle.

- Apology and Retraction

Though not a full defence, an apology or retraction may mitigate the damages awarded. The Defamation Law of Lagos State (Cap. D5, Laws of Lagos State 2015) recognizes this mitigation when the apology is made promptly and sincerely.

Defences in Criminal Defamation

- Truth and Public Benefit

Under Section 375 of the Criminal Code and Section 392(2) of the Penal Code, a statement is defensible if it is true and it was for the public good that it be published. Both elements must coexist, a true statement published maliciously and without public benefit can still be criminal.

- Privileged Publications

Sections 376 of the Criminal Code and 393 of the Penal Code recognize privilege for publications made in judicial, legislative, or official proceedings, or fair and accurate reports thereof.

- Fair Comment on Public Affairs

The defence of fair comment applies where the statement represents a genuinely held opinion on a matter of public concern, made without malice. This principle was reaffirmed in Guardian Newspapers Ltd v. Ajeh (2011) 10 NWLR (Pt. 1256) 574.

- Innocent Publication

Under Section 377 of the Criminal Code, a person is not liable if they neither knew nor intended the publication to be defamatory and took reasonable care to prevent it.

- Consent of the Aggrieved Party

Where the publication was made with the consent of the person defamed, it cannot constitute an offence. This is recognized under Section 378 of the Criminal Code.

Misuse of Judicial Process and Consequences

The courts have consistently warned against the misuse of their time and process. Bringing frivolous or unfounded defamation claims, or using the police to pursue personal grudges, is viewed as a serious abuse. In Saraki v. Kotoye (1992) 9 NWLR (Pt. 264) 156, the Supreme Court defined abuse of court process as using judicial procedure for purposes it was not intended.

Such misuse can attract punitive costs, dismissal of the case, and in extreme cases, disciplinary action against the erring party or counsel. The court’s time is too valuable to be spent on matters that, as judges often say, “go to no issue.” The justice system exists to correct genuine wrongs, not to satisfy vanity or vendetta.

Conclusion

The law of defamation in Nigeria is built upon balance, the balance between protecting the dignity of individuals and upholding the freedom of expression vital to democracy. Every lawyer, journalist, and citizen must understand this delicate equilibrium.

Before rushing to court or the police over alleged defamation, one must pause and ask himself, Is this truly a matter for criminal law, or simply a civil grievance? The misuse of police powers and the abuse of court processes only weaken the integrity of our justice system.

As the courts have often reminded, the law is not a weapon for oppression but an instrument of order and fairness. Defamation law, properly understood, protects truth, honesty, and responsible expression not malice, ego, or misuse of authority.

Amb. Ibrahim Muhammad Usman is a law graduate, advocate of intergenerational justice and equity, a passionate voice for Sustainable Development Goals, Inclusive policy and good governance, AI safety and governance in Africa, and climate justice. He can be reached via imuhammadusman66@gmail.com or 08145101965.

Amb. Ibrahim Muhammad Usman is a law graduate, advocate of intergenerational justice and equity, a passionate voice for Sustainable Development Goals, Inclusive policy and good governance, AI safety and governance in Africa, and climate justice. He can be reached via imuhammadusman66@gmail.com or 08145101965.

by Legalnaija | Sep 13, 2025 | Blawg, Uncategorized

NBA Lagos Branch Embarks on a Protest Against the Nigerian Navy’s Disregard of Court Judgment

The Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), Lagos Branch, on Friday, 12th September 2025, staged a peaceful protest against the Nigerian Navy’s unlawful signal, declaring its member, Vice Admiral Dada Olaniyi Labinjo (Rtd.), as a “deserter,” in defiance of a valid judgment of the National Industrial Court.

Led by the Branch Chairman, Mrs. Uchenna Ogunedo Akingbade, members of the Executive Committee and several lawyers converged at Marine Bridge, Apapa, where they were met with a heavy security presence of armed Police, Military personnel, DSS operatives, and Lagos State Neighbourhood Safety Corps officers.

Despite initial hostility, the lawyers stood their ground and by 11:00 a.m., marched to NNS Beecroft, Apapa, where they were received by Naval officers and later addressed by Commodore Paul Ponfa Nimmyel.

Mrs. Akingbade presented the purpose of the protest:

To condemn the Navy’s disregard of a subsisting Court judgment.

To deliver a protest letter to the Chief of Naval Staff through the Flag Officer Commanding.

However, Commodore Nimmyel refused to accept the letter on behalf of the Navy, insisting it should be delivered directly to the Chief of Naval Staff in Abuja, while suggesting dialogue before protest. In response, Mrs. Akingbade firmly countered that:

He who comes to equity must come with clean hands. You cannot call for dialogue while disobeying a Court order and persisting in unlawful actions against our member.

Present at the protest were Branch officers, including Mr. James Sonde (Vice Chairman and Chairman, Human Rights Committee), Mr. Kelechukwu Uzoka (Secretary), Mrs. Oge Mokelu (Treasurer), Mr. Oliver Omoredia (Publicity Secretary), branch members such as Mrs. Oyinkansola Badejo-Okusanya, Mrs. Chinelo Okonkwo, Mr. Shola Lamid, Mr. Victory Ilugo and prominent branch members turned out for the protest.

The NBA Lagos Branch reaffirmed its commitment to defending the Rule of Law, stressing that disobedience of Court orders by institutions poses a grave danger to Nigeria’s democracy.

by Legalnaija | Sep 6, 2025 | Uncategorized

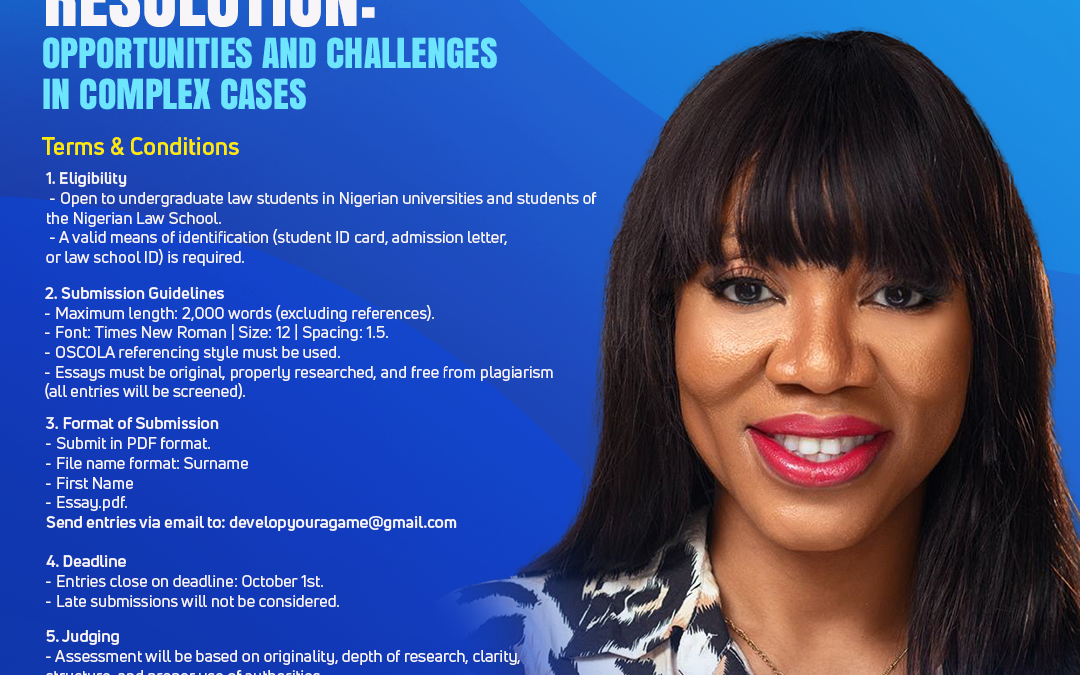

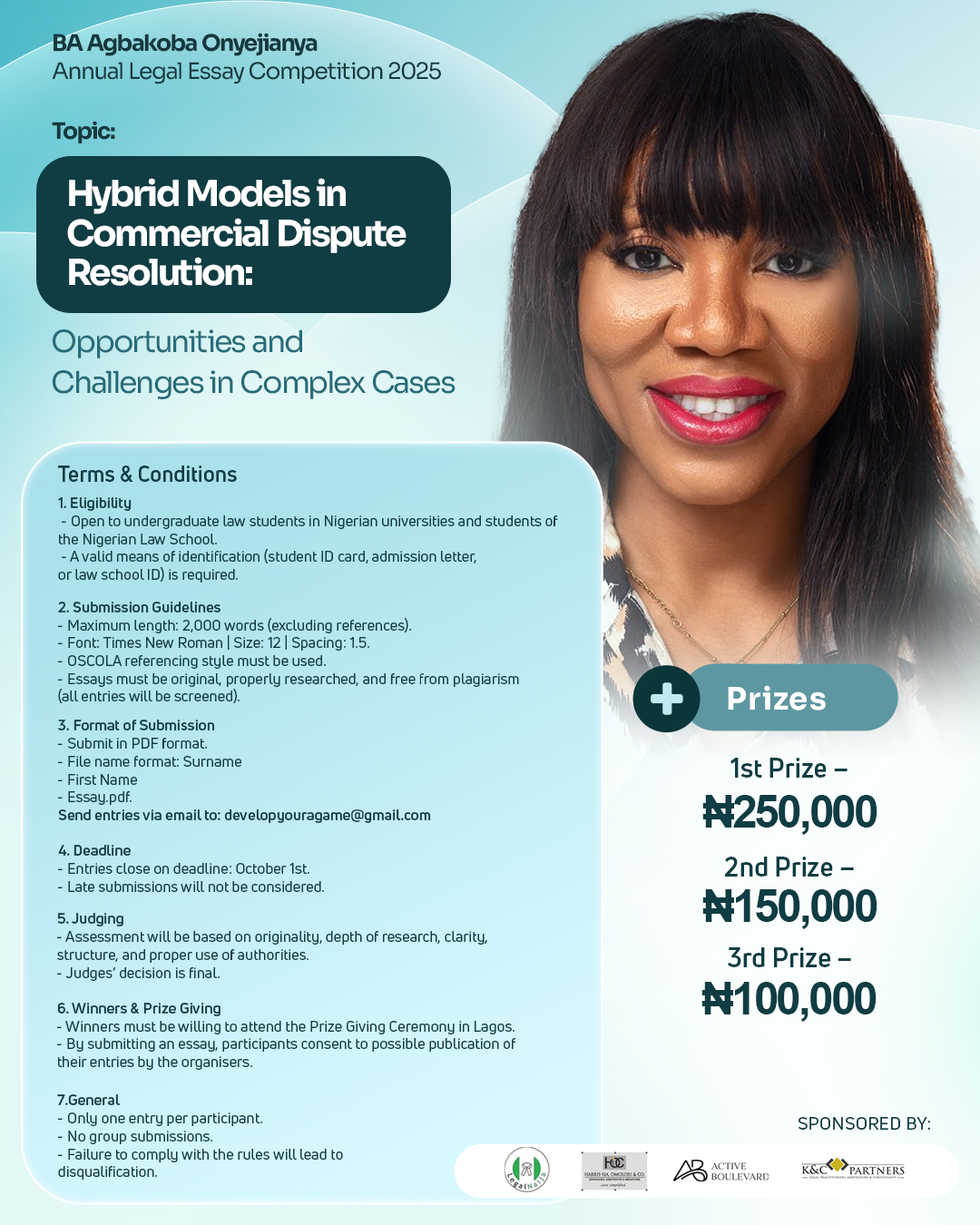

CALL FOR ENTRIES: Agbakoba Onyejiuwa Annual Legal Essay Competition 2025

Are you a Nigerian law student with a sharp mind and a passion for legal innovation? This is your moment to shine.

📌 Topic:

Hybrid Models in Commercial Dispute Resolution: Opportunities and Challenges in Complex Cases

💼 Eligibility:

Open to undergraduate law students in Nigerian universities and students of the Nigerian Law School. Valid student ID or admission letter required.

📄 Submission Guidelines:

– Max 3000 words (excluding references)

– Times New Roman | Size 12 | Spacing 1.5

– OSCOLA referencing format

– PDF format only

– Original, plagiarism-free work (plagiarism test will be conducted)

📅 Deadline:

1st October, 2025

📧 Submit to:

developyouragame@gmail.com

🏆 Prizes:

– 🥇 1st Prize – ₦250,000

– 🥈 2nd Prize – ₦150,000

– 🥉 3rd Prize – ₦100,000

📝 Winning essays may be published on CRWI, Bar & Bench, and other top legal blogs. This is more than a competition—it’s a platform to amplify your voice in the legal community.

Tag your law school crew. Let’s raise the bar. ⚖️

LegalEssayCompetition #AgbakobaOnyejiuwa2025 #Legalnaija #LawStudentsNG #CRWI #BarAndBench

by Legalnaija | Aug 24, 2025 | Uncategorized

THE NDPR TRUST MARK: A MISLEADING AND COUNTERPRODUCTIVE TOOL IN NEED OF REFORM

By Olumide Babalola

Introduction

Under Nigeria’s data protection framework, certain categories of business entities are required to conduct and file annual data protection compliance audits (now formally referred to as Compliance Audit Returns (CAR) under sections 6(d) and 61(g) of the NDPA and Article 10 of the GAID). When the system was first introduced in 2019, the regulator issued confirmation emails as evidence of filing. However, upon transitioning to the Nigeria Data Protection Commission (NDPC), the practice shifted to issuing NDPR Trust Mark Certificates as proof of compliance with audit-filing obligations.

Although this innovation initially appeared professional and standardized, it quickly created misconceptions. Many organizations and even some privacy professionals, interpreted the Trust Mark as confirmation of substantive compliance, rather than a simple acknowledgment of audit filing. The result is widespread misrepresentation, with businesses brandishing the Trust Mark as proof of full compliance while neglecting their broader obligations under the law. This article examines the meaning of trust marks, why the NDPR Trust Mark (as currently issued) is misleading, and why reforms are necessary to avoid further confusion and counterproductive outcomes.

Understanding Trust Marks in Privacy and Data Protection Parlance

Globally, trust marks (also called privacy seals, certification marks, or trust seals) are visual indicators (logos, badges, or images) that signify compliance with predefined data protection or privacy standards. Typically, they are awarded by independent third parties and serve as signals of credibility to consumers, regulators, and stakeholders.

Needless to say, that the Nigerian idea of trust mark (although tweaked) was inspired by the EU GDPR’s creation of certification mechanism in Europe even though they continue to struggle with their problems of heterogeneity of the trust mark regime. In the EU, for example, the GDPR introduced certification mechanisms that serve as trust marks. These are often tied to regulated services such as electronic signatures, timestamps, and other qualified trust services, thereby enhancing confidence in digital transactions.

At their core, trust marks communicate that an organization has been evaluated and approved by a neutral third party against specific privacy or security criteria.

Why the NDPR Trust Mark is Misleading

Outdated Legal Reference: As of August 23, 2025, the Trust Mark issued by the NDPC still carries the label NDPR. Whereas the principal legislation since 2023 is the NDPA, not the NDPR. Continuing to issue certificates under the old regulatory regime only fuels legal and operational confusion especially in the light of conversations around the current status of the NDPR as extant or otherwise.

False Impression of Evaluation: Unlike global trust marks, the NDPR Trust Mark does not represent a thorough evaluation against defined privacy benchmarks. Instead, it merely confirms that an organization has filed its annual audit report. The absence of evaluation metrics, scoring frameworks, or substantive approval processes means that the Trust Mark conveys an inflated sense of compliance.

Conflicts in the Nigerian Audit Process: In Nigeria, audits are conducted by Data Protection Compliance Organisations (DPCOs), which are engaged and paid by the very companies they audit. This raises a fundamental conflict of interest: “he who pays the piper dictates the tune.” Furthermore, under Article 10 of the GAID, the obligation to conduct audits lies primarily with controllers and processors themselves. The law merely requires filing through a DPCO. Thus, the DPCO is not an independent evaluator but rather a service provider executing instructions. Without standardized scoring or evaluation metrics, the process does not amount to a true third-party certification.

Misconstrued Approval by NDPC: The most damaging misconception is the idea that the Trust Mark signifies NDPC’s approval of total compliance. In reality, audit reports are meant to highlight gaps, not certify perfection. The NDPC’s acceptance of audit filings cannot and should not be equated with substantive compliance. For instance, a company may dutifully file its audit while still failing to meet obligations around transparency, data subject rights, security safeguards, or purpose limitation. The Trust Mark, however, enables them to market themselves as “compliant,” which misleads the public and stakeholders alike.

Counterproductive Effects of the Trust Mark

The original purpose of audits was to help organizations identify and fix weaknesses in their privacy practices. Unfortunately, the Trust Mark has turned this process into a box-ticking exercise. This problem is especially acute among digital lenders and fintech companies, which often require the Trust Mark to secure licenses. Once obtained, many companies ignore the gaps identified in their audits, preferring instead to rely on the certificate as proof of compliance year after year.

The result is an illusion of compliance where organizations technically comply with the audit-filing requirement while ignoring broader obligations. Meanwhile, the NDPC’s true objective (i.e safeguarding data subjects’ rights) is undermined. In short, while the issuance of Trust Marks may inflate statistics on “compliance,” it does not reflect the reality of privacy protections in practice.

Recommendations for Reform

Replace the initial Trust Marks with Acknowledgment Notices: Instead of issuing Trust Marks upon audit filing, the NDPC should issue simple acknowledgment documents. These should confirm only that an audit has been filed, without implying broader compliance.

Introduce Remediation Timelines: Since audits reveal compliance gaps, the NDPC should require controllers to submit remediation plans with clear timelines for addressing deficiencies.

Adopt a Scoring and Evaluation Framework: True trust marks should only be awarded after substantive evaluation. The NDPC should create scoring metrics to assess compliance maturity, allowing organizations to be benchmarked and rated transparently.

Clarify the Scope of the Trust Mark: The NDPC should consistently emphasize that audit filing does not equate to substantive compliance. Public communication must reinforce this distinction.

Issue Trust Marks Post-Verification: Only after an organization has demonstrably closed the gaps identified in its audit should it be eligible for a genuine trust mark.

Conclusion

The NDPR Trust Mark, in its current form, is misleading, counterproductive, and ripe for reform. While intended as a symbol of compliance, it has instead become a shield for minimal effort and a source of confusion for stakeholders. For Nigeria’s data protection ecosystem to mature, the NDPC must realign the Trust Mark with its true purpose: a rigorous, independent certification of substantive compliance. Anything less risks perpetuating a culture of checkbox compliance while leaving the fundamental rights of data subjects unprotected.

by Legalnaija | Aug 7, 2025 | Uncategorized

Leading international law experts have called for increased integration of women in the development and implementation of clean energy transition policies and programs to achieve a just and inclusive transition agenda that leaves no one behind.

This recommendation was made at an online workshop organized by the Committee on Women, International Law, and Development of the International Law Association Nigeria (ILA Nigeria). Themed, ‘Energy for All: Bridging Gender Gaps in the Green Transition,’ the event also marked the official launch of the Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy special issue on ‘Gender Justice and Energy Transition in the Global South.’ The special issue, edited by the Committee Chair, Dr. Pedi Obani, and Committee member, Dr. Adenike Akinsemolu offers new theoretical and empirical insights on the intersections of gender and energy justice.

Moderated by Committee Vice Chair Barrister Titilope Akosa, the event featured leading international experts including the President of ILA Nigeria, Professor Damilola Olawuyi, SAN; the immediate past Director-General of the National Council on Climate Change Secretariat, Dr. Nkiruka Maduekwe; and the Head of the Renewable Energy Unit at First City Monument Bank (FCMB), Ms. Chinma George. The webinar also featured presentations by Dr. Opeyemi Gbadegesin, Dr. Eduardo Pereira, and Dr. Hilary Okoeguale, who authored papers for the special issue.

Committee Chair, Dr. Pedi Obani, who is also an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Bradford in welcoming participants emphasised that, “In Nigeria, as in much of the Global South, women are not only disproportionately affected by energy poverty and environmental degradation – they are also powerful agents of change driving sustainable solutions. Yet, structural and institutional barriers continue to limit their participation access to resources and decision-making power.”

In his keynote address, Professor Damilola Olawuyi, SAN, who is also an Independent Expert on the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights, lamented the pervasive lack of women in leadership roles in the energy sector, which is at risk of being replicated in clean energy transition programs. Calling for the equitable distribution of the benefits and burdens of development policies, the Learned Silk stated that, ‘There is a clear and urgent need to mainstream a gender perspective in clean energy transition programs and policies.’ He identified five dimensions of justice for a gender-aware energy transition: cosmopolitan justice, procedural justice, reparative justice, social justice, and distributive justice. According to him, realizing these justice imperatives requires providing tailored opportunities for women to access the necessary financing, technologies, training and education needed for them to play active and leading roles in developing and commercializing green innovation and eco-entrepreneurial ventures. Professor Olawuyi stressed that achieving these goals demands innovative, gender-aware and equitable laws and policies.

In the second keynote, Dr. Nkiruka Maduekwe discussed the uneven impacts of the climate crisis on women and the underuse of women’s knowledge, leadership, and expertise in the energy sector. She pointed out that, ‘Despite the fact that women bear the brunt of energy poverty, we account for over 70% of off-grid energy users. We lack access to affordable energy.’ Dr. Maduekwe also noted the scarcity of women’s stories in climate-related reporting, despite their producing most wood fuel and being the primary managers of energy in households. She proposed solutions such as increasing girls’ and women’s exposure to STEM education, introducing a gender lens to legal and policy frameworks, and promoting gender-informed storytelling. She also called for public participation in Nigeria’s ongoing efforts to develop its third Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement.

Guest speaker Ms. Chinma George highlighted gender gaps in the current transition framework, focusing on women’s experiences with energy poverty and their limited opportunities for employment and leadership in energy. She underlined FCMB’s role in addressing these issues by empowering women through access to finance – like zero-interest loans – promoting green products, improving financial literacy, and fostering public-private partnerships.

The presentations by authors of papers in the special issue reinforced discussions about the gender gaps in current transition programs across the Global South, including in Nigeria and Brazil, and proposed solutions through training policymakers on gender analysis, providing seed grants for women’s climate research, disaggregated data collection, and equitable constitutional design processes. Dr. Pedi Obani also highlighted the Committee’s ongoing projects geared at driving gender inclusion in critical sectors, such as energy, water, sanitation, and hygiene, and other areas. She called for collaboration towards building policies and systems that advance women’s rights and holistically cater to of all segments of society.

ILA Nigeria is a branch of the International Law Association, which was founded in Brussels in 1873. The Nigerian Branch of the ILA regularly hosts innovative lectures, seminars, conferences, and other capacity development programs to advance the study and understanding of international law in Nigeria. Its committees, such as the Committee on Women, International Law and Development, serve as its focal points for contributing to research, capacity development, and dialogue around key thematic areas of international law. To learn more about ILA Nigeria, its activities, and events, visit http://www.ilanigeria.org.ng

Amb. Ibrahim Muhammad Usman is a law graduate, advocate of intergenerational justice and equity, a passionate voice for Sustainable Development Goals, Inclusive policy and good governance, AI safety and governance in Africa, and climate justice. He can be reached via imuhammadusman66@gmail.com or 08145101965.

Amb. Ibrahim Muhammad Usman is a law graduate, advocate of intergenerational justice and equity, a passionate voice for Sustainable Development Goals, Inclusive policy and good governance, AI safety and governance in Africa, and climate justice. He can be reached via imuhammadusman66@gmail.com or 08145101965.