by Legalnaija | Apr 7, 2023 | Law, Training

Recently, President Buhari signed the Business Facilitation (Miscellaneous Provision) Act, 2023, a legislative intervention by the Presidential Enabling Business Environment Council, PEBEC, which amends 21 business-related laws, removing bureaucratic constraints to doing business in Nigeria.

Other laws recently signed into law are the Copyright Act, 2022, and various constitutional amendments, including the creation of the NNPC Limited, all geared towards making Nigeria a progressively easier place to start and grow a business.

It is therefore important that lawyers are well equipped and informed on how these laws affect their client’s businesses and the business community at large. This is why Lawlexis has put together a stellar faculty of lawyers and business experts to deliver masterclasses on these new developments in corporate law.

Modules:

– Tax Law

– Ethics and Corporate Governance

– Energy Law

– ESG And Risk Management

– Capital Markets And Securities Law

– Commercial Arbitration

Members of Faculty

– Mr. Tolu Aderemi (Partner Perchstone & Graeys)

– Mrs. Folashade Alli (Partner, Folashade Alli & Associates)

– Dr. Ayodele Oni (Partner, Bloomfiled Law Practice)

– Mr. Chukwua Ikwuazom SAN (Partner, Aluko & Oyebode)

– Miss Bukola Iji (Partner, SPA Ajibade & Co.)

– Mr. Dayo Adu (Partner, Famsville Solicitors)

Theme: New Developments In Corporate Law

Date: 25th and 26th May, 2023

Time: 9am – 5pm daily

Venue:

- Onsite: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

- Offsite: (ZOOM)

Registration Details;

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 15th May, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg Link: https://bit.ly/3KRMX1v

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Fee: 50,000

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 15th May, 2023)

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3KEW99c

Bank Transfer Details;

Name: Lawlexis International

Bank: Fidelity Bank

Acct Num: 4011176564

Registration fee covers lecture materials, and certification. Plus you can get 10% discount when you use the voucher code: CORPORATELAWYER23. Persons who should attend include lawyers at all levels. For enquiries, please contact: Lawlexis – lawlexisinternational@gmail.com or 09029755663.

by Legalnaija | Jan 16, 2023 | Law, Training

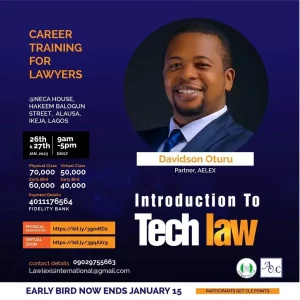

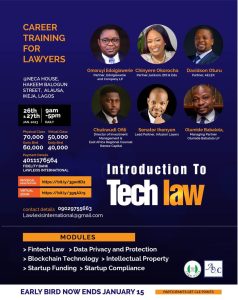

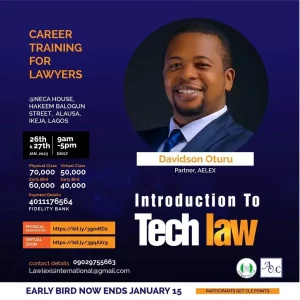

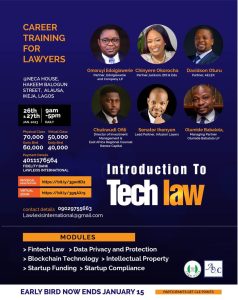

DAVIDSON OTURU

Davidson is a Partner at Aelex in the firm’s IP/TMT, Corporate/Commercial and Dispute Resolution Practice Groups. He advises clients on trans-border issues relating to Intellectual Property Law, Information and Communication Technology Law, Financial Technology (FinTech) Law Cybersecurity, Telecommunications, Data Protection and Privacy.

His clients are in a variety of industries, including banking, information technology, private equity, financial services, pharmaceuticals and capital markets.

He has significant experience in representing and advising clients on trans-border issues relating to financial technology (fintech), project finance, digital assets, blockchain technology data protection and cyber security breaches, white collar crimes and data privacy. He assists clients with remediating high-stakes multi-jurisdictional cybersecurity breaches, negotiating complex technology transactions, franchising and intellectual property licensing.

He provides practical and strategic advice to leading telecommunications service providers, mobile network operators, infrastructure owners and investors, technology suppliers and equipment manufacturers and financial institutions.

His unique IP practice focuses on contentious and general IP work as he works closely with clients across various industries to manage, protect and advance their portfolio of IP rights, including trademarks, patents and design covering multiple jurisdictions. He represents clients in enforcement proceedings involving unfair competition, copyright infringement, passing off and trademark infringement.

Davidson regularly advises companies on compliance with corporate, statutory and regulatory matters. He advises on business start-up, labour & employment, corporate due diligence and corporate restructuring. He advises foreign investors seeking to establish entities in Free Trade Zones and also advises various multinationals on the framework for foreign direct/portfolio investments in Nigeria.

His regulatory advisory work also includes the provision of legal support to technical advisory groups funded by the USAID and DFID that are aimed at providing high-level support to Federal and State Government agencies on their Public Private Partnership (PPP) programmes.

In recognition of his thought leadership and continuous contributions to the fintech ecosystem, he was ranked as a leading lawyer by Chambers and Partners in its 2022 Fintech Guide.

To register use the links below;

Physical Session:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg Link: https://bit.ly/3godtD2

Virtual Session (ZOOM) Fee: 50,000

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3gqAXr9

Persons who should attend include lawyers, founders, tech compliance officers and stake holders in the Tech Industry at all levels. For enquiries, please contact: Lawlexis – lawlexisinternational@gmail.com or 09029755663.

by Legalnaija | Sep 2, 2022 | Law

Introduction

Child labour refers to work engaged in by children which is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to the children and also interferes with their schooling.[1] Article 32 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognizes the rights of children to be free from economic exploitation and works that are harzardous or interfere with their general wellbeing and development. ILO 138 prescribes the minimum age for work and ILO 182 addresses the worst forms of child labour. Recommendation 146 accompanies ILO 138 and directs state signatories to develop national policies with provisions on poverty alleviation, promotion of decent jobs for adults, free education among other factors which have a direct effect on child labour.[2] Equally relevant is the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which is hinged on 17 Sustainable Developments Goals (SDG). SDG 8 is for the promotion of sustained, inclusive and economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. SDG (Target) 8.7 is to take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms.

SDG 8.7 in Nigeria

Nigeria is signatory to the key UN Conventions aimed at child protection and currently has a National Action Plan on the elimination of child labour for the years 2021-2025. This action plan is intended to coincide with SDG 8.7 on eliminating all forms of child labour by the year 2025. With more than half of the current year gone by, the race to accomplish target 8.7 has barely two years and four months to go. International child right actors are concerned at the slow pace of attaining to SDG 8.7 of eliminating all forms of child labour by the year 2025 globally.[3] The Durban Call to Action[4] which followed the Fifth Global Conference on the Elimination of Child Labour held between the 15th to the 20th of May 2022 in Durban reiterated the challenge to address the elimination of all forms of child labour. Based on current statistics, the COVID pandemic caused setbacks in global efforts to eliminate child labour, shrunk previous gains and ballooned the number of children trapped in child labour.[5] UNICEF data suggests that 26% of children aged 5 to 11 in West and Central Africa are subjected to child labour.[6] The Situation Analysis of Children in Nigeria 2022 report that about 14 million children between the ages of 5 -14 are currently engaged in child labour.[7] Beyond policy and print, it is not immediately obvious how Nigeria intends to close up the gap by 2025. While Nigeria anticipates a change of government in the coming year and possibly, an improvement in its economic conditions, it is not likely that the country will be sufficiently close to SDG 8.7 by 2025.

UNICEF’s multisectoral approach to child labour identifies that an effective coordination across systems is key to ensuring protection and access to services.[8] Systems include nutrition and food, private sector, services for CAAC (children and armed conflict), social protection, empowered families, and education and skills. The coordination of these systems which do not stand alone but are intricately interwoven rests on several stakeholders but squarely on the government.

One basic system in the multisectoral approach is nutrition and food. This ties into the need for food security. The challenge of food insecurity in Nigeria is not peculiar to children but affects them greatly because of their vulnerability. The causes of food insecurity in Nigeria are easily traceable to insufficient production, inefficient policies, civil insecurity, corruption and low technology for processing and storage.[9] A few of these causes are not peculiar to Nigeria such as the effects of climate change on food production which has affected some northern states with significant desert encroachment, dwindling farmlands and water scarcity.[10] The country however needs to surmount the challenge of food insecurity if there would be any gains in eliminating child labour.

Another important system is the private sector. The Government’s efforts to achieve SDG 8.7 depends greatly on stakeholder involvement. The Unicef Guidance Note for Action on Child Labour and Responsible Business Conduct charges the business community to contribute its quota to eliminating child labour by guaranteeing decent work and living wages to employees.[11] The Nigerian business community on its part is faced with a business environment where the cost of doing business is relatively high. According to the World Bank ranking on the ease of doing business for 2020, Nigeria ranked 131 out of 190 countries considered.[12] The indices used pertain to registering businesses, obtaining permits, electricity supply, getting credit, protecting minority investors, enforcing contracts, registering property, paying taxes, resolving insolvency and trading across borders. The ranking is based on select cities and thus may not reflect the actual position of other parts of the country. There are several other challenges including security concerns, high cost of generating power and needed infrastructure, multiple layers of regulatory fees and more recently, compulsory sit-at-home exercises in some parts of the country on certain days of every week which culminate in a difficult business environment for the business community. In the face of these challenges, there is little justification for the government to charge the Nigerian business community to pitch in by guaranteeing sufficient wages for employees in the fight against child labour.

Services for CAAC is fast becoming one of the most critical systems in the elimination of child labour in Nigeria. This owes to the fact that the effect of children in armed conflict cascades into every other system and threatens to wipe out the gains the country has made in its effort to eliminate child labour. Amnesty International has reported that no fewer than 1,500 children have been abducted from schools in the last eight years.[13] Insecurity in Nigeria is convoluted and spirals into depriving children of education, denying children proper nutrition, increasing the number of children at risk of armed conflicts both as recruits and hostages and clearly forcing more children into child labour at the hand of their captors. Over 11,000 schools are reported to have been shut down owing to terrorist activities in the country.[14] Erstwhile pupils and students now forced to stay home for their safety, add to the number of children aged 5 to 17 who will have to engage in work for hours longer than is suited to their age bracket including hazardous work. Abducted children turned into child soldiers in turn cause terror that keeps farmers away from their farms and raises poverty levels. The National Action Plan for the elimination of child labour runs the risk of remaining a printed policy if the challenge of CAAC is not addressed in practical terms.

The systems of social protection and empowered families are affected by factors such as inflation, high rates of unemployment and scarcity of disposable income. Though Nigeria has slipped out of the bottom rung of the global poverty ranking, the World Poverty Clock shows that poverty levels in the country are currently rising.[15] Pre COVID, 4 in 10 Nigerians were estimated to be living in poverty.[16] The pandemic necessitated the closure of schools and loss of jobs which invariably left children with the short end of the stick. Out of jobs parents meant engaging children in menial jobs not requiring much skill or training to support the family. Post pandemic, the number of Nigerians that have slipped into poverty have increased. As households become poor, members of those households who are children become more susceptible to child labour. Many more children have been made available to assist in household chores with other families. Some of such children do not go to school at all as their parents receive monthly salaries for their work. A decent number of such children do get some level of education though the value of such education may be relatively low or attendance at school may be staggered. The lack of quality education or in some cases the lack of education at all leads to low levels of literacy and vocational skills thereby impacting on the opportunities open to such child labourers in adulthood and perpetuating the cycle of child labour.[17] Article 3 of the CRC recognizes that in all actions concerning children, the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration. Set against the backdrop of the economic reality of the families of child labourers, the decision to send off their children to work for an income or in exchange for education no matter how deficient appears to them to be the best decision for the child. The decision is nonetheless questionable.

The education and the skills systems are up against the challenges of the preceding systems and cannot be meaningfully pursued by the government, until the associated systems such as insecurity and poverty are out of the way.

Conclusion

The multisectoral approach to child labour reveals a lot of gaps in Nigeria’s quest to attain to SDG 8.7. The government must first be seen to exercise political will in the right direction to achieve the much-needed collaboration with stakeholders and industry groups. Terrorism, food insecurity and poverty will need to be addressed for any meaningful gains to be made in education and the elimination of child labour. The government thus needs to take deliberate steps towards a coordinated approach to ensure that SDG 8.7 moves from print to action. Gains may be slow, and the target of 2025 may not be feasible, but meaningful collaboration among stakeholders will guarantee the rescue of many children from child labour by 2025.

Eberechi May Okoh LLM, ACTI, MCIArb

Eberechi May Okoh LLM, ACTI, MCIArb

[1] https://www.ilo.org/moscow/areas-of-work/child-labour/WCMS_249004/lang–en/index.htm, accessed 8 August 2022.

[2] https://www.ilo.org/ipec/facts/ILOconventionsonchildlabour/lang–en/index.htm accessed 8 August 2022.

[3] Guidance Note for Action, Child Labour and Responsible Business Conduct https://www.unicef.org/reports/child-labour-and-responsible-business-conduct assessed 10 August 2022.

[4] What is the Durban Call to Action? | 5th Global Conference on the Elimination of Child Labour (5thchildlabourconf.org) accessed 8 August 2022.

[5] Covid-19 Pandemic Fueling Child Labor | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org) accessed 11 August 2022.

[6] https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-labour/ assessed 6 August 2022.

[7] Situation Analysis of Children in Nigeria https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/media/5861/file/Situation%20Analysis%20of%20Children%20in%20Nigeria%20.pdf accessed 8 August 2022.

[8] Guidance Note for Action, Child Labour and Responsible Business Conduct https://www.unicef.org/reports/child-labour-and-responsible-business-conduct assessed 10 August 2022.

[9] S. Matemilola and I. Elegbede, ‘The Challenges of Food Security in Nigeria’ (2017) 4 Open Access Library Journal 9.

[10] Bonaventure N. Nwokeoma and Amadi Kingsley Chinedu, ‘Climate Variability and Consequences for Crime, Insurgency in North East Nigeria’ 8 (2017) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 173.

[11] Guidance Note for Action, Child Labour and Responsible Business Conduct https://www.unicef.org/reports/child-labour-and-responsible-business-conduct assessed 10 August 2022.

[12] NGA.pdf (doingbusiness.org) assessed 10 August 2022.

[13] https://guardian.ng/news/eight-years-after-chibok-11536-schools-closed-over-1500-pupils-abducted/ assessed 6 August 2022.

[14] https://guardian.ng/news/eight-years-after-chibok-11536-schools-closed-over-1500-pupils-abducted/ assessed 6 August 2022.

[15] https://worldpoverty.io/map accessed 8 August 2022.

[16] Nigerian Poverty Assessment 2022 https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099730003152232753/pdf/P17630107476630fa09c990da780535511c.pdf accessed 8 August 2022.

[17] Guidance Note for Action, Child Labour and Responsible Business Conduct https://www.unicef.org/reports/child-labour-and-responsible-business-conduct assessed 10 August 2022.

by Legalnaija | Mar 8, 2022 | Blawg, Law

“it’s money 2.0, a huge, huge, huge deal” – Chamath Palihapitiya. Venture Capitalist.

Hardly does a week go by, that there is no news about cryptocurrency or Bitcoin. It’s either the urgency to invest in it or its volatile nature. Infact, Nigeria through its Central Bank activated on Monday, 25th October, 2021 it’s digital currency (Central Bank Digital Currency – CBDC) called ‘e-Naira’

Advocate of digital currency see it not just as the future of money but it’s present.

“Bitcoin will do to banks what email did to the postal industry” – Rick Falkvinge (Swedish Pirate Party Leader).

“as the value goes up, heads start to swivel and skeptics begin to soften. Starting a new currency is easy, anyone can do it. The trick is getting people to accept it because it is their use that give the money value” – Adam B. Levine.

There are those who do not see any value in Digital Currency (cryptocurrency). They don’t understand it nor care to, they consider it a fraud/scam.

“What value does cryptocurrency add? No one has been able to answer that question to me” – Stevie Eisman.

“It is a mirage basically, it’s a very effective way of transmitting money and you can do it anonymously and all that. A check is a way of transmitting money too. Are checks worth a whole lot of money just because they can transmit money?… The idea that it has some huge intrinsic value is just a joke in my view – Warren Buffett

Digital currency is any means of payment for goods and services that exists in a purely electronic form, it is not physically tangible like a money note or coin. It is a medium for daily transactions but it is not cash. It is important to state that the money in your online bank account is not digital currency because it takes on a physical form when you withdraw it from an ATM (Automated Teller Machine). In 2020, Warren Buffett had this to say ” cryptocurrency basically has no value and they don’t produce anything. They don’t reproduce, they can’t mail you a check, they can’t do anything and what you hope is that somebody else comes along and pays you more for them later on, but then that person’s got the problem. In terms of value: zero”

Like it or not, there are people who belong to the same school of thought as Warren Buffett.

Before answering the question, If it is possible to buy a property with digital money? Let’s understand what digital money (currency) is and how it works?

The fact that it doesn’t exist in physical form does not mean it isn’t worth anything. The basis for the creation of digital currency was to fix the flaws with the way money is transmitted from one person to another.

There are different types of digital currency:

- Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC):- are currencies issued by the Central Bank of a country. It is a virtual form of a country’s fiat currency. It aims to ease monetary policy implementation by removing intermediaries (banks and financial institutions) and establishing a direct connection between the government and the average citizen. It can also be used for financial inclusion. Examples; e-Naira (Nigeria), Sand Dollar (Bahamas), DCash (Antigua and Barbuda). According to Alanticcouncil.org CBDC tracker, 87 countries are now exploring a CBDC. 7 countries have now fully launch a CBDC, Nigeria being the latest country to launch its CBDC.

- Cryptocurrencies:- are digital currencies designed using cryptography (Blockchain technology). Examples; Bitcoin, Ethereum, Binance coin, Cardano, Tether, Solana, Polkadot, Doge coin etc.

- Virtual Currencies: are digital representations of value, its transactions occur solely on online networks or the internet. They are largely unregulated, issued and controlled by its developers. They are used and accepted electronically among members of a specific virtual community i.e. private organizations or groups of developers.

Examples are tokens and cryptocurrencies. They are not used as a payment method in mainstream society, but mostly in gaming communities.

Digital currencies, Virtual currencies, cryptocurrencies all sound and work in a similar way, however they are different. All Virtual currencies and Cryptocurrencies are digital currencies but not all digital currencies are virtual Currencies, for example; CBDCs are not virtual currencies or cryptocurrencies.

Digital currencies can be regulated or unregulated. CBDC is an example of a regulated digital currency and Bitcoin is an example of an unregulated digital currency. Cryptocurrencies uses cryptography to secure their networks while Virtual currencies may or may not use cryptography.

Digital Currency is built through the Blockchain technology, which is a digital ledger where all transactions involving a digital currency are stored. All digital currencies are created, stored and exchanged on their own separate Blockchain networks. A digital currency’s blockchain network is a digital ledger of all transactions on that currency. New transactions are grouped into blocks, each block is confirmed and validated by multiple users through out the network, before being added at the end of the chain. Every user has their copy of the ledger and it is constantly updated.

How do people use digital currency? How can fraud and manipulation be eliminated from a transaction between users? This leads us to a process called ‘ Mining’. Miners confirm all the transactions inside a new block so it can be recorded and sealed on the Blockchain ledger. To regulate the supply of the currency and control inflation, the blockchain software protocol makes it increasingly difficult for miners to generate hashes and confirm new blocks as the network grows in size. This guarantees accountability, transparency and stability for networks and their currencies.

Remember that digital currency does not exist in physical form, then how do I store it?

When digital currency are mined on their blockchain and transferred between users, they must be stored in a digital currency wallet. The wallets are pieces of software which can be used to store digital currencies securely for an indefinite period of time. All digital currency wallets have a public key and at least one private key.

When you send and/or receive digital currency

,the transaction is recorded on the ledger, everyone can see but it documents only your wallet location and none of your personal identifiable information this ensures anonymity. The private key can only be seen by the owner of the wallet. It contains the cryptographic information needed to authorize transfers out of the wallet, this key should never be shared.

WHY IS DIGITAL CURRENCY (CRYPTOCURRENCY) SO POPULAR?

- It is seen by some as the currency of the future therefore there is the urgency to buy them now before they become more valuable.

- There are no intermediaries, no third party financial institution is required to oversee the transactions.

- It is decentralized. There is no single data center where all transactions data is stored. Data from this digital ledger is stored on hard drives and serves all over the world.

- Because there are no intermediaries, transmission of money is faster and cuts back on costs.

- There is no need for a physical storage and safekeeping unlike cash.

- Digital Currency transactions can become censorship resistant and impervious to tracking by government and other authority.

- It ensures the inclusion of groups of people previously excluded from the economy. For instance; the unbanked can still participate in the economy using digital currency in their online wallets or mobile phones.

- It simplifies accounting and recording keeping for transactions through technology.

As with all things, there are upsides and downsides. The disadvantages of digital currency are:

- It is an uncharted and unfamiliar territory for most policy makers thus presenting challenges on the policy framework.

- It is a target for hackers who can steal from digital wallet

- It has its own cost. You need digital wallet to store your digital currencies, system that uses Blockchain also have to pay transaction fees.

The use of digital currency is growing everyday and may take center stage in financial transactions. Buying a property, be it for home ownership or investment purposes is a huge and important decision and security is a critical element in real estate investment. Presently, you can pay for a property using cash, bank transfers and credit card payments. The question is can I buy or sell a property using digital currency?

Nigerians are heavy cryptocurrency users, second to the United States of America. According to paxful platform, in 2020, 1.1 million cryptocurrency trades were recorded per month in Nigeria.

Why is cryptocurrency popular in Nigeria?

Some use it to protect their savings against the Naira depreciation, others as an alternative source of income, as a way to get around foreign currency restrictions etc. Despite, it being a high risk investment, its usage and trading in Nigeria continue to increase.

Back to the question, if one can buy or sell a property using digital currency? Yes, it is possible in some markets though it is a novel concept. For instance, the first property to be sold for Bitcoin was in Austin, Texas in 2017. It is important that you understand cryptocurrencies, digital Currencies, how it works, before using them for real estate assets.

In certain markets and jurisdiction, the Crypto- property market is gradually opening up. There are property sellers and buyers willing to accept cryptocurrencies. There are also Property Lawyers in crypto real estate transactions. In October, 2017, the first Ethereum real estate transaction was conducted, Michael Arrington (Founder of TechCrunch) bought an apartment in the Ukrainian market using an Ethereum smart contract.

Before you buy a property using cryptocurrencies, you must:

- Understand and educate your about digital Currencies and Cryptocurrencies. How it works, the market and the risks involved.

2 .Find a seller willing to accept it as payment. In some markets, there are sellers and agents who list their properties stating their willingness to accept cryptocurrencies, though some use this as a strategy to generate buzz for their properties. Some request for payment split between cryptocurrencies and traditional currency.

- Set the standard. Cryptocurrency is highly volatile therefore when using it to purchase a property, it is best to set the purchase price of the property in fiat currency (government issued currency. Modern paper money e.g. US Dollars, British Pounds, Naira etc). The contract must expressly state how the cryptocurrency will be settled. For instance: if the purchase price for the property is 20 Million Naira and the price/value of the cryptocurrency drops at the close of the purchase transaction, the buyer must make up the difference or where the price/value of the cryptocurrency increases in value and the transfer has been done, the surplus should be returned to the buyer.

- Verify: Always conduct your due diligence because the use of cryptocurrencies in real estate transactions is a novel concept, cryptocurrencies are volatile, susceptible to hacking and can be used for money laundering.

- Find the right people to work with. Because many people still do not understand how it works, others see cryptocurrencies as ‘fake internet money.

CONCLUSION

Despite the advantages in using cryptocurrencies in real estate transactions, it must be understood that it has a high price volatility risk. The value can change in seconds during the course of a sale transaction which may lead to the seller opting out. Further it is a new concept, many are not familiar with it and thus it would be difficult to find a seller willing to accept it over the traditional currency particularly in the Nigerian property market. Where one even finds a willing seller, he/she may be nervous about closing a transaction because of its price volatility.

In the real estate market, cryptocurrencies are considered as very risky or an unknown, therefore there are very few players willing to work with it

REFERENCES

- Investopedia

- com/how digital currency works.

- com Forbes.com Bloomberg.com Thisday.com Rockethq.com Chainalysis

- org/CBDC Tracker Wikipedia

- ng

Ololade O. Soda-Pereira is a Legal practitioner, Writer and Researcher with 15 years experience in legal practice and specialization in the following practice areas; Property Law, Estate Planning and Succession, Commercial Law, Legal Audit for SMEs and financial institutions. She is known for her Law and Me Series currently on her social media handles where she answers questions on the problems and challenges faced in the acquisition and investment in real estate and offers legal tips for SMEs to scale up their businesses and improve their service delivery.

by Legalnaija | Oct 31, 2021 | Blawg, Law

Money is the lifeline of any business, without funding is it practically impossible to expand or even grow your business. Oftentimes Entrepreneurs seek venture capital or external investment from angel investors.

Many times these startups assume that all they need is a disruptive business concept and a clear path to growth. But this isn’t always the case,. Below we explore five of the most important legal issues that professional investors are likely to review in a standard due diligence process before deciding to make an investment in an early-stage company.

- Corporate Governance

Whether your company is a corporation, limited liability company (LLC) or partnership, when seeking investment, you should ensure the following:

- the basic governance structure is finalized and agreed to by all stakeholders;

- the organizational documents are adequate and complete;

- all agreements of the board of directors/managers or shareholder actions are properly reflected in the minutes;

- Additionally, the company should be treated as a separate entity (and not as the alter ego of the founders or of another business);

- and the equity records of the company should be complete.

Upon deciding whether to make a venture investment, an investor will likely request a review of these organizational documents to gain a better perspective of the actions the company has taken in the past. One of the most common mistake startup companies make is that they fail to address properly ownership and measure of equity owned which leads to avoidable problems. This can be avoided by seeking legal counsel at the onset to ensure that it is done correctly.

- Shareholder Agreement

The easiest way to make clear what all of the equity holders’ rights are in a company is to have a shareholders’ agreement. Some of the pivotal provisions of this agreement include:

- Voting arrangements,

- restrictions on share transfer,

- “tag and drag” rights in the event of a sale,

- anti-dilution provisions and

- rights of first offer or refusal.

In my experience, many startups discuss these issues verbally some even prepare drafts but never get to the signing stage and this leads to uncertainty for subsequent investors in the company and what rights all parties involved have. The absence of a final and signed shareholders’ agreement may also allow certain equity holders to block a potential venture investment and to hold the transaction hostage unless they are given preferential rights.

- Intellectual Property

If your company is centered around or built upon its intellectual property, then it is essential that there is no confusion about the ownership of intellectual property associated with the company. An investor will expect to see signed intellectual property assignment agreements, assigning any potential ownership rights or claims to the company. Furthermore, depending on the nature of your intellectual property, it is essential that you conduct proper due diligence to confirm that you are not infringing on third-party intellectual property right.

- Written Contracts

Although an agreement does not have to be in writing to be enforceable, it a good idea to ensure that all of your material agreements are in writing, contain all important terms, and are properly signed by all parties. The kinds of agreements that should be in writing include:

- vendor and supply agreements,

- customer agreements,

- warranty and guaranty terms and

- employment agreements

Prior to making an investment, an investor will likely request to review your material contracts to gain a clearer picture of your business’ obligations.

One key thing you must note is that, when negotiating a written contract, some third parties will include certain provisions within the contract, including indemnification, non-compete, license, and limitation of liability provisions which may impact negatively on your company, so be on the lookout for these provisions because they eventually become an issue during investor due diligence and may adversely affect your company’s value to a potential investor. As always, make it a point of duty to get legal help before you sign a contract.

- Understanding the Regulatory Issues relating to your business

Maneuvering the regulatory landscape relating to your business is a must. For example, if your business is in the tech space, you must ensure it is in tune with data privacy laws of the country of Origin and adheres to regulatory provisions. Before making an investment, investors will want to ensure that your business plan is not endangered due to regulatory concerns. It is essential that you see legal counsel to help you identify any potential regulatory issues and to confirm that such regulatory issues where they exist will not adversely impact your business model.

About the writer:

Omoruyi Edoigiawerie is a Legal Practitioner and Lead Partner at the Law firm of Edoigiawerie and Company LP – a full service law firm with depth of proven experience and expertise in corporate commercial transactions and a strong bias for Startup and Entrepreneurship Law.

He is a member of the Nigerian and American Bar Associations as well as several professional bodies.

Omoruyi is the brain behind the UyiDLaw brand where he shares very insightful Legal nuggets (UyisNuggets) to help businesses grow and thrive. Through his platforms, he provides mentorship and business linkage support.

He can be reached at omoruyi@uyilaw.com.

by Legalnaija | Oct 31, 2021 | Blawg, Justice, Law

INTRODUCTION

With population growth and the attendant civilization, new ways of criminal machinations keep emerging. It would therefore, not be incorrect to say that crimes and criminality are on the increase. Our courts, and in general the criminal administration system are overwhelmed by the plethora of criminal cases that grace their floors on a daily basis. Consequently, our prisons are congested with number of inmates, with many awaiting trial.

Based on a 2016 data, Lagos State has the highest number of prison inmates’ population. The state recorded 7,396 prison inmates population as against a prison capacity of 3,927, closely followed by Rivers and Kano States with 4,424 and 4,183 prison inmates population. It was also reported that the Kirikiri Prisons in Lagos, which was built to accommodate 1,700 inmates, had 3,553 as of June 2017, over-shooting its capacity by 1,853 inmates. The Nigerian Prisons Service (NPS) Controller-General, Ahmed Ja’afaru, bemoaning the situation said that a total of 68,250 people were behind bars in Nigeria. However, only 32 per cent (or 21,903) of the inmates had been convicted. This means 46,351 people (or 68 per cent), who are awaiting trial put the system under avoidable stress.

Recently, Lagos State Government has activated moves to considerably bring down the number of inmates awaiting trial in prisons across the State through the implementation of the plea bargain aspect of the Administration of Criminal Justice Law 2011 (ACJL).The purpose of this paper is to discuss the concept of plea bargaining as a veritable tool in the administration of criminal justice in Nigeria.

MEANING OF PLEA BARGAINING

A plea is the response that a person accused of a crime gives to the court when the offence with which he is charged and which is contained in the charge sheet or information is read to him by the court. In general, the accused person could plead guilty or not guilty to the crimes. Where the court takes his plea and the court after trial is satisfied that the prosecution has proved his case beyond reasonable doubt, the court would proceed to sentence the accused person accordingly. On the other hand, plea bargain means a negotiated agreement between a prosecutor and a criminal defendant whereby the defendant pleads guilty to a lesser offence or to one of the multiple charges in exchange for some concession by the prosecutor; usually a more lenient sentence or a dismissal of the other charges. Section 494 of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act 2015 defines plea bargain as;

The process in criminal proceedings whereby the defendant and the prosecution work out a mutually acceptable disposition of the case; including the plea of the defendant to a lesser offence than that charged in the complaints or information and in conformity with other conditions imposed by the prosecution, in return for a lighter sentence than that for the higher charge subject to the Court’s approval.

In simple terms, it is an agreement in criminal trials between the prosecutor and the accused person to settle the case in exchange for concessions. It could take the form of a Charge Bargain, Count Bargain or Sentence Bargain.

PROCEDURE OF PLEA BARGAINING; A CUE FROM LAGOS STATE

Generally, criminal procedure encompasses the laws and rules governing the mechanisms under which crimes are investigated, prosecuted, adjudicated, and punished. In other words, it is a manual of events that apply from the apprehension, trial and punishment of an accused.

The duration of criminal procedure coupled with the poor performance of the institutions in the criminal justice system in Nigeria has led to dawdling of criminal investigations and trials. The effect of this is that many suspects are arrested and detained without trial while some others are incarcerated for a long period of time due to the slow pace of criminal investigation or trial in Nigeria.

The nature of plea bargain can go a long way in decongesting prisons in Nigeria and foster a democratic system. This is because its procedure is quick as it allows parties involved including the victim to reach an agreement without going through the rigors of criminal trial. Commendably in Lagos state, the plea bargaining agreement is provided for under ACJL and has no limitation to any offence or to any person. Thus, a prosecutor can reach an agreement with an accused person wherein he will be given a reduced sentence, count or charge.

Under the ACJL, the prosecutor may only enter into plea bargaining agreement after consultation with the police officer responsible for the investigation of the case and the victim if reasonably feasible; and with due regard to the nature of and circumstances relating to the offence, the defendant and the interest of the community.

When the agreement is in progress, the prosecutor if reasonably feasible shall afford the complainant or his representative the opportunity to make representations to the prosecutor regarding.

- The contents of the agreement; and

- The inclusion in the agreement of a computation or restitution order.

Where a plea agreement is reached, the prosecutor shall inform the court of the agreement and the judge or magistrate shall inquire from the defendant to confirm the correctness of the agreement. If the answer is in the affirmative, the presiding judge or magistrate shall ascertain whether the defendant admits the allegations in the charge to which he has pleaded guilty and whether he entered into the agreement voluntarily and without undue influence. The court after satisfying itself on all of the foregoing will do one of the following:

- Convict the defendant on his plea of guilty to the offence as stated in the charge and agreement

- If not satisfied, the court will enter a plea of not guilty and order that the trial proceed.

Significantly, the presiding judge or magistrate before whom criminal proceedings are pending shall not participate in the plea bargaining agreement. However he can give relevant advice to them regarding possible advantages of discussions, possible sentencing options or the acceptability of a proposed agreement.¹³ But in sentencing the defendant after the conviction, the judge or magistrate is to consider the sentences agreed upon in the plea agreement. If the sentence is considered appropriate, then the agreed sentence would be imposed on the defendant. However if the court decides that the defendant deserves a heavier sentence, the defendant shall be informed. Upon the defendant being informed, the defendant has two options. One, the defendant can abide by his plea of guilty as agreed upon and agree that subject to the defendant’s right to lead evidence and to present arguments relevant to sentencing, the presiding judge or magistrate proceed with the sentencing. The second one is that he withdraws from his plea agreement in which event the trial shall proceed de novo before another presiding judge or magistrate. Where the trial proceeds de novo before another presiding judge or magistrate, the following must be observed

- No reference shall be made to the agreement

- No admissions contained therein or statements relating thereto shall be admissible against the defendant; and

- The prosecutor and the defendant may not enter into similar plea and sentence agreement.

ESSENTIAL INGREDIENTS THAT MUST BE PRESENT IN A PLEA BARGAIN AGREEMENT

A plea bargaining agreement must contain the following:

- The agreement must be in writing and contain the following specifics or state

- That the defendant has been informed that he has a right to remain silent;

- Also he has been informed of the consequences of not remaining silent

iii. That he is not obliged to make any confession or admission that could be used in evidence against him

- The full terms of the agreement and any admission made must be stated; and

- The agreement must be signed by the prosecutor, the defendant, the legal practitioner and the interpreter (if used).

CONCLUSION

Plea bargain has over time been recognised as the most useful means of quick disposal of criminal trials in our criminal justice.They include the fact that the accused can avoid the time and cost of defending himself, the risk of a harsher punishment, and partially eliminate the publicity the trial will involve. It also saves the prosecution time and expense of a lengthy trial, and both parties are spared the uncertainty of going to trial. Ultimately, the court is saved the burden of conducting a trial on every crime charged.

Those against the concept have rightly argued that it could be prone to abuse if not well regulated. For instance, in the case of the defunct Oceanic Bank Managing Director, Mrs Cecilia Ibru, who was accused of stealing over N190 billion. She entered a plea bargain with the EFCC. She was convicted on 25 counts of fraud, ordered to refund only N1.29 billion and sentences to six months imprisonment part of which she allegedly spent in a Highbrow Hospital. This has been seen by many as a mere “slap on the wrist”.

It is our view that despite the inherent fears and reservations some people may nurture with the proposal by the Lagos state government to utilize plea bargain, there is no doubt that the desirability of plea bargain in prison decongestion out-ways its undesirability, thus other states in Nigeria should adopt similar approach. However, that is not to play down the need to take necessary stringent measures to prevent abuse of the process by prosecutors.

Finally, the ultimate card lies with the judiciary as the law allows them to consider sentence agreed upon and accept or refuse such sentence where necessary. Thus, judges and Magistrates should be more proactive and take all necessary steps to curb any attempt to abuse plea bargaining.

References:

Prison Statistics: Prison Population by Total Detainees, Prison Capacity and Number of Un-sentenced Detainees by State and Year and Prison Inmate Population by Gender 2011-2016

<https//www.proshareng.com/admin/upload/reports/10669-NBSPRISONFULLREPORT201120 16-proshare.pdf> accessed 14 June 2019.

<https://bscholarly.com/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-lawyer-daily-tasks-lawyers-go-through/> accessed 14 June 2020.

<https://bscholarly.com/why-is-democracy-the-best-form-of-government/> accessed 14 June 2021.

Prison Congestion: Acting on Buhari’ <https://punchng.com/prison-congestion-acting-on-buharis-alarm/> accessed 14 June 2019.

Ibid.

O Olayanju, ‘The Relevance of Plea Bargaining in the Administration of Justice System in Nigeria’ [December 2011/January 2012] (VIII) (2&3) LASU Law Journal 35

<http://www.lasu.edu.ng/publications/law/oluseyi_olayanju_ja_1.pdf> accessed 14 June 2019.

B Garner, Blacks Law Dictionary (8ᵗʰ Edition, USA: West Publishing Company 2004) 1190.

ACJL, s 76(2) (a) & (b).

The prosecutor for the purpose of the foregoing provisions (s. 75 & 76) means a LAW OFFICER; see ACJL, s 76(11).

ACJL, s 76(3).

ACJL, s 76(6).

ACJL, s 76(7).

ACJL, s 76(7) (a) & (b).

ACJL, Section 76(5). ¹⁴ACJL, Section 76(8) (a) . ¹⁵ACJL, Section 76(8) (c).

ACJL Section 76(9) (a) & (b).

ACJL, Section 76 (10) (a)-(c).

ACJL, Section 76(4).

FRN v Lucky Igbinedion [2014] LPELR – 22760 (CA), Justice Helen Ogunwumiju listed the advantages of plea bargains.

ACJL, s 76(8); ACJL, s 367(9).

Edeh Samuel Chukwuemeka

University of Nigeria, Nsukka (400L)

samueledeh04@gmail.com

by Legalnaija | Jul 21, 2021 | Law

ADMISSIBILITY OF AN UNREGISTERED LAND INSTRUMENT: DISSECTING BENJAMIN -V- KALIO (2018) 15 NWLR (Pt 1641) 38, ANAGBADO -V- FARUK (2019) 1 NWLR (Pt 1653) 292 AND ABDULLAHI & ORS -V- ADETUTU (2020) 3 NWLR (Pt 1711) 338,

INTRODUCTION

A land instrument is a vital document in proving legal title and equitable interest in land. This paper examines the current position of the law on the admissibility of an unregistered land instrument by dissecting the three Supreme Court cases of Benjamin -V- Kalio (2018) 15 NWLR (Pt 1641) 38, Anagbado -V- Faruk (2019) 1 NWLR (Pt 1653) 292 and Abdullahi & ors -V- Adetutu (2020) 3 NWLR (Pt 1711) 338.

THE POSITION OF THE LAW BEFORE 2017

The law on admissibility of an unregistered land instrument was governed by the various land instrument registration law of the states. The position was that an unregistered land instrument is not admissible to proof title to land, however, such unregistered instrument is admissible to prove payment of money, possession, or an equitable interest in land. See the cases of Ojugbele v. Olasoji (1982) 4 SC 31, Akintola & Anor. v. Solano (1986) 2 NWLR (Pt 24) 589, Ogbimi v. Niger Construction Ltd (2006) 9 NWLR (Pt. 986) 474) and Anyabunsi v. Ugwunze (1995) 6 NWLR (Pt.401) 255.

THE SUPREME COURT’S DECISION AFTER 2017.

On 15 December 2017, a full panel of the Supreme Court sitting, delivered a landmark decision in Benjamin v. Kalio (2018) 15 NWLR (Pt 1641) 38 changing the position of the law. In that case the apex Court declared unconstitutional, null and void section 20 of the Land Instruments (Preparation and Registration) Law, Cap. 74, Laws of Rivers State, 1999 and by extension similar provisions of the Land Instruments Law of the various states. The previous position of the law was based on the premise that evidence was not on the exclusive legislative list under the 1963 Constitution. It was under the constitutional scenario that the federal legislature and the regional (State) legislatures re-enacted the Evidence Ordinance of 1945 as Evidence Act and Evidence Laws respectively. However, in 1979, the situation changed. Under the 1979 Constitution, evidence was brought into the exclusive legislative list as item 23. It has remained so since then. It is currently item 23 of the exclusive legislative list in Part 1 in the Second Schedule to the extant Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended, 2011). A piece of evidence pleaded and admissible in evidence under the Evidence Act cannot be rendered unpleaded and inadmissible in evidence by a Law enacted by the House of Assembly of a State under the prevailing constitutional dispensation.

This newly informed position was followed by the Supreme Court in Anagbado v. Faruk (2019) 1 NWLR (Pt 1653) 292, where it was held as follows:

‘’The Law Cap. 85 of Kaduna State (section 15 thereof), in so far as it purports to render inadmissible any material and relevant piece of evidence that is admissible in evidence under the Evidence Act, 2011, is to that extent inconsistent with the Evidence Act, enacted by the National Assembly pursuant to the powers vested in it by section 4(2) of the Constitution and Item 23 of the Exclusive Legislative List set out in Part I of the Second Schedule to the Constitution. Evidence is Item 23 in the Exclusive Legislative List. I am of the firm view that, in view of section 4(5) of the Constitution read with section 4(2) and Item 23 of the Exclusive Legislative List set out in Part I of the Second Schedule to the Constitution, in the event of section 15 of the Law, Cap.85 of Kaduna State being in conflict or inconsistent with any provisions of the Evidence Act, the provisions of the Evidence Act shall prevail. The sum total of all I am saying, on this issue, is that section 15 of the Kaduna State Law, Cap. 85 cannot render inadmissible exhibitP2 which evidence is material, relevant and admissible in evidence under the Evidence Act, 2011. A piece of evidence admissible in evidence under the Evidence Act cannot be rendered inadmissible in evidence by any law enacted by the House of Assembly of any State.’’

In 2019, the Supreme Court in Abdullahi & Ors v. Adetutu (2020) 3 NWLR (Pt 1711) 338 did not follow the new position of the law it laid down but applied the old principle of law that an unregistered land instrument is not admissible to proof title to land but admissible to prove payment of money, possession, or an equitable interest in land. This has led litigants to believe that the Supreme Court has overruled the earlier decision in Benjamin v. Kalio and Abdullahi v. Adetutu and that the old position of law is still valid. The principle of law that where there are two conflicting decisions of the Supreme Court, the latter in time should be followed supports this impression. see Cardoso v. Daniel (1986) 2 NWLR (Pt 20) 1, Isaac v. Obiuweubi v. CBN (2011) 3 SCNJ 166.

A closer analysis of these three cases and other principle of laws reveals that the decision in Abdulahi v. Adetutu did not overrule the decisions in Benjamin v. Kalio and Abdullahi v. Adetutu. The reasons are as follows:

First, the cases of Benjamin v. Kalio and Anagbado v. Farouk on one hand and Abdullahi & ors v. Adetutu on the other hand have one major factor that distinguishes them, which is the interpretation of the Constitution in relation to the validity of the Land Instrument law of the state. In Abdullahi & ors v. Adetutu, the Supreme Court did not determine the validity of the law. In the earlier two cases the Supreme Court effectively determined the law to be null and void while in the latter case the apex Court decided the case based on the issues and argument before the court viz: a document is admissible based on what it is pleaded for. Benjamin v. Kalio was decided by a full panel of the Supreme Court sitting which interpreted the Constitution and effectively overruled the previous position of the law. Abdullahi & Ors v. Adetutu was not decided by a full panel of the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court intends to overrule its previous position of the law, it sits as a full Court. see Paul Odi & anor v. Gbaniyi Osafile & anor (1985) 1 NWLR (Pt 1) 17 S.C. Effiom v. State (1995) 1 NWLR (Pt 373) 565-566 S.C. A principle or rule used in arriving at a decision in a case is an important factor in deciding where the ratio of the Court lies. See N.A.B v. Barrie N.G (1995) 8 NWLR (Pt 413) 257 Sifax Nig ltd v. Migfo Nig Ltd & anor (2018) 1-2 S.C 1, Fawehinmi v. NBA (No. 2) (1989) 2 NWLR (Pt 105). The constitutional principle used in deciding the two earlier cases is an important factor in distinguishing these cases.

Secondly, in our hierarchy of law, the Constitution is supreme, see Section 1 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999; judicial precedent is lower in hierarchy. A judicial precedent cannot overrule the provisions of the constitution, except the judicial precedent is on interpretation of the Constitution (i.e., where there are conflicting interpretations of a provision of the Constitution).

Lastly, Abdullahi & Ors v. Adetutu is an anomaly. A case law that goes against an avalanche of other case law authorities must pale into significance and cannot be followed or relied upon. See Onuoha v. State (1989) 1 NSCC 411 at 421 where Oputa J.S.C stated as follows:

‘’a just decision of the case will be a decision in accord with the many many authorities and previous decisions of our Courts as well as English decisions which our Courts have followed and adopted. A decision that throws all our existing authorities to the wind, will no doubt be an alarming decision, but hardly a just decision. With respect, it was thus foolhardy for the lower Court to have followed and relied on the decision of the Court of Appeal in Otiki v. Bajehson when there are many other authorities of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal to the contrary. It is incumbent on, and essential for, all the players in the administration of justice system to take pains and acquaint themselves with developments in the law.’’

The statement of Oputa J.S.C has been followed in Afelumo & Ors v. Ojo & Ors (2013) LPELR-19976 C.A, and Olukosi v. Nigerian College of Aviation Technology, Zaria & anor (2014) LPELR-24009 C.A.

CONCLUSION

Abdullahi & Ors v. Adetutu is not authority that an unregistered land instrument is not admissible to proof title to land, it is good authority for the position of law that a document is admissible only for what it is pleaded and tendered for. The correct position of the law is that an unregistered instrument affecting land is admissible in evidence to prove title because an evidence rendered admissible under the Evidence Act cannot be rendered inadmissible by a state law as laid down in Benjamin v. Kalio (2018) 15 NWLR (Pt 1641) 38 and Anagbado v. Faruk (2019) 1 NWLR (Pt 1653) 292.

Adewale Sontan is a legal practitioner and has a keen interest in dispute resolution. He is a Counsel in various litigation proceedings involving corporate institutions, individuals and government agencies. He can be contacted via sontanadewale@gmail.com

Adewale Sontan is a legal practitioner and has a keen interest in dispute resolution. He is a Counsel in various litigation proceedings involving corporate institutions, individuals and government agencies. He can be contacted via sontanadewale@gmail.com

by Legalnaija | Jun 27, 2021 | Court, Justice, Law

Nigeria is a federating unit comprising of 36 states and a Federal Capital Territory. The States have their justice architectures but these Courts are not the final Courts of the land. In the hierarchy of the judicial system in Nigeria, the Supreme Court is the highest court and its decisions are final.

Access to justice is a right that is constitutionally guaranteed under sections 6 and 46 of the 1999 Constitution. The court is an essential service provider in our society which is why the court is referred to as the last hope of the common man. What happens when the court is not within the reach of these common people?

The highest court in a State in Nigeria is the State High Court while the Highest Court in the Federation is the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court has original and appellate jurisdiction. It’s appellate jurisdiction is over appeals from the Court of Appeal. Appeals are lodged to the Supreme Court by aggrieved parties over the decisions of the Court of Appeal.

Being the highest and final court in the Federation, it is expected that the Supreme Court should be within the reach of the common people and must be easily accessible. But this is far from being the case. Can you imagine travelling more than 10,000 kilometres before you can get access to justice? The Supreme Court of Nigeria only sits in Abuja and no where else.

Yes, section 230 (1) of the 1999 Constitution created only one Supreme Court of Nigeria. In the same manner, section 237 established only one Court of Appeal. Yet, the Court of Appeal has various divisions in the States of the Federation. No wonder in 2018, the then Chief Justice of Nigeria, Hon. Justice Samuel Walter Onnogen said that the diary of the Supreme Court is filled till 2023. The implication is that the diary of the Supreme Court is filled till 2026 as at now. And that is the highest court. How can the common man have access to justice in such a situation?

Presently, there are appeals pending at the Supreme Court for more than 7 years and no date has been fixed for the hearing of those appeals. In some cases, either or both parties in the appeal would be dead before the Supreme Court fixed the appeal for hearing.

The question begging for an answer is “In other to decongest the Supreme Court, can the Supreme Court have registry in the States of the Federation and sit in the States of the Federation besides the Federal Capital Territory?” In the past, some lawyers have suggested that the Supreme Court should be splited so that each regions in the country can have its own Supreme Court.

I am of the view that the Supreme Court does not need to be splited in such a manner. Orders 17, 18 and 19 of the Supreme Court Rules, 1985 have already empowered the Supreme Court to be able to decide where it would or will sit to decide appeals. For the sake of convenience the said Orders have been reproduced hereunder:

“17. Sessions of the Court shall be convened and constituted and the time, venue and forum for all sessions and for hearing interlocutory applications shall be settled in accordance with directions to be given by the Chief justice.

18. The sitting of the Court and the matters to be disposed of at such sittings shall be advertised and notified in the Federal Gazette before the date set down for hearing of the appeal:

Provided that the Court may in its discretion hear any appeal and deal with any other matter whether or not the same has been so advertised.

19. The Court may at any time on application or of its own accord adjourn any proceedings pending before it from time to time and from place to place.”

From the wordings of the above Rules, the Chief Justice of Nigeria is empowered to determine where the Supreme Court will sit and that it must not be in Abuja alone. I believe that what was in the mind of the drafter of this Rules is to bring the Supreme Court closer to the common man and not to remove the Supreme Court from the common man or to leave it within the reach of the rich alone.

Justice has suffered due to the distance between the Supreme Court and the masses. If the Supreme Court had been closer to the common man, more grievances would have been ventilated in the Court than on the street. The cost of appealing to the Supreme Court from States that are unfortunate enough to be far from Abuja is exorbitant and astronomically high. The cost of appeal has discouraged many aggrieved party from appealing to the Supreme Court. A past President of Nigeria once said that education is not for everyone. And I ask, is justice not also for everyone?

I strongly believe that the justices of the Supreme Court are sincerely doing their best in attending to appeals and seeing that they are disposed of as quickly as possible. There are however certain things which acts as clogs in the wheel of justice. One of which is the limited numbers of the Justices of the Supreme Court there are in Nigeria. Section 230 (2) (b) of the 1999 Constitution limited the number of Justices of the Supreme Court to Twenty One including the ChiefJustice of Nigeria. Then at least five of these 21 justices are to constitute a panel. That is obviously too tasking for these Justices who are usually close to their retirement age.

This Constitutional provision can frustrate the will of the Chief Justice if he wants to implement the suggestions in this work. How on earth can 21 Justices of the Supreme Court cover 36 States and the Federal Capital Territory without being worn out? Section 237 (2) (b) of the 1999 Constitution allows the Court of Appeal to have a minimum of 49 Justices. One will then wonder why the number of Justices in the Supreme Court is seriously limited to 21!

It has become a norm that if a party with no good case wants to work injustice against another litigant, he would hide the case in the Supreme Court. Why? This is so because before “the book of remembrance” will be opened on such an appeal, the parties might have lost interest in the case. If the Supreme Court will not become a Court to issue academic decisions in the nearest future, a lot needs to be done.

One of which is that the provisions of Section 230 (1) (b) of the 1999 Constitution must be amended to increase the number of Justices that can be appointed to the Supreme Court.

Secondly, in other to fast track the appeals to and at the Supreme Court, the Court should have registry in the States of the Federation and also the Chuef Justice should ensure that the Court can either rotate its sittings in the States or should have divisions in the States of the Federation. In this way, justice will be more accessible to the common man who was once scared away with the cost of accessing justice.

Adedapomola G. Lawal, Esq

Adedapomola G. Lawal, Esq

by Legalnaija | Jun 16, 2021 | Blawg, Law

The recent comment by President Muhammadu Buhari on the existence of grazing reserve gazette in the country and his directive to the Hon. Attorney General of the Federation, Abubakar Malami, SAN to dig out same for possible implementation has expectedly been generating heated reactions mostly negative from Nigerians, the most recent coming from the red chamber spokesperson, Senator Ajibola Bashiru.

Senator Basiru, a lawyer by calling, contends that there is currently no grazing route law at the federal level or in the Laws of the Federation for Mr. President to implement or for Abubakar Malami, SAN, to dig out for implementation.

Senator Bashiru is right. The only grazing law that existed in Nigeria was the Northern Nigerian Grazing Law of 1964/1965 that was enacted by the then Northern Nigeria Legislative Assembly and therefore with the collapse of regionalism or the fall of the first Republic and the coming into effect of the Land Use Act on the 29th day of March 1978, all pre-existing land laws were/are deemed extinguished. In fact, not even the protective provisions of Section 325 of the current 1999 Constitution will save the grazing law of Northern Nigeria for implementation at both regional and federal levels in the face of the existence of the Land Use Act which itself has Constitutional flavor having been specifically mentioned in Section 315(5)(d) of the 1999 Constitution.

By the protective provision of Section 315(1) of the Constitution, an existing law shall have modifications as may be necessary to bring it into conformity with the provisions of this constitution and shall be deemed to be an Act of the National Assembly to the extent that it is a law with respect to any matter on which the National Assembly is empowered by the Constitution to make laws and a law made by a House of Assembly to the extent that it is a law with respect to any matter on which a House of Assembly is empowered by the Constitution to make laws. What this means is that assuming that the grazing law of the defunct Northern Nigerian Legislative Assembly still

exists, same must be brought in conformity with the Provisions of the 1999 Constitution and the Land Use Act to be valid and subsisting.

In any event assuming but not conceding that the grazing law of the Northern Nigerian Legislative Assembly of 1964/1965 can be preserved, saved or protected, same cannot be applicable in all states of the Federation, same having been made by only the Legislative Assembly of Northern Nigeria. It lacked the status of a nationwide general application.

Aside from this, with the coming into effect of the Land Use Act which by virtue of section 315(5)(d) is a Constitutional enactment, the 1964/1965 grazing land reserve law automatically becomes a back bencher having been effectively consumed by the provisions of the Land Use Act which by its preamble vests all land comprised in each state (except land vested in the Federal Government or its agencies) in the Governor of the State to hold in trust for the people and henceforth be responsible for allocation of the land in all urban areas to individuals and organizations for residential, agricultural, commercial and other purposes while similar powers with respect to non-urban areas are conferred on the Local Government.

It is instructive to note that Section 6 of the Land Use Act empowers local government to grant Customary Right of Occupancy to any person or organization for use of the land in the Local Government Area for grazing purposes or other purposes auxiliary to agricultural purposes with a caveat however provided under section 6(2) of the Land Use Act to the effect that no single customary right of occupancy shall be granted in respect of an area of land in excess of 500 hectares if granted for agricultural or grazing purposes except with the consent of the Governor.

In other words even if any local government desires to allocate grazing land having been empowered constitutionally to so do, it cannot allocate a land area of 500 hectares without the consent of the Governor for grazing or agricultural purposes.

What this logically means is that even if the 1964 Northern Nigeria grazing Law is preserved by the present Constitution, same must be

brought in conformity with the extant provisions of the 1999 Constitution and the Land Use Act which automatically will require the consent of the Governor if the land area allocated is up to 500 hectares. In further support of the contention that the 1964 Grazing laws of the defunct Northern Nigerian Legislative Assembly are not in existence even in the current 19 states of Northern Nigeria, Section 34 of the Land Use Act settles the debate (especially where the land in question is undeveloped) in that, all pre-existing rights or interests thereto, are deemed extinguished and depending on the size of the land, claimants may be entitled to only one plot or half a hectare.

by Legalnaija | Jun 16, 2021 | Law

“Ultra vires” is a Latin Legal term translated (in English) to “beyond the powers”. The term is used to describe an act which requires legal authority or power but is then done/completed outside of or without the requisite legal authority (lexisnexis.co.uk). The act of a person or authority, is said to be ultra vires when the person/authority acts beyond the scope of the powers and purposes provided to him/it by law. Ultra vires acts are generally void. (see: Communities Economic Development Fund v. Canadian Pickles Corp., (1991) CarswellMan 402 (S.C.C.)) (PracixalLaw). See also, NOSDRA v. Mobil Prod. (Nig.) Unltd (2018) 13 NWLR (Pt.1636) 334. Where legal authority is required in order to /make/enact a law or take certain actions, any law made or action taken without any such enabling law or outside or in excess of the powers granted by law is said to be or to have been taken “ultra vires” and accordingly void and of no effect. The opposite of ultra vires is “intra vires”, (translated to “within the powers”), a term used to refer to an act done under/within proper legal authority. An ultra vires act is going to be totally void and it’ll not bind anyone; is not enforceable. Besides, any person with requisite locus standi (legal standing) may commence a legal action either for an injunction to restrain a planned ultra vires act or to nullify an act taken or law made ultra vires the person making the law or doing the act.

A June 14, 2021 news item in a popular online (news) media platform in Nigeria, Thenigerialawyer, comes under the headline, “50% Of Disputed Tax Amount To Be Paid Into Court Account” and carries the following report, inter alia: “Anyone who intends to challenge a tax assessment in court must pay 50 per cent of the amount in dispute into an interest-yielding account of the Federal High Court before the case can be heard.The new requirement is contained in a recent practice direction issued by the Chief Judge, Justice John Tsoho, under Order 57, Rule 3 of the Federal High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2019″. I have gone through a copy of the Federal High Court (Federal Inland Revenue Service) Practice Direction 2021, which was made on May 31, 2021to take effect on June 01, 2021. In respect of applications or actions filed by the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) to enforce payment of taxes by an alleged defaulting taxable Person, Order V Rule 3 of the Practice Directions provides as follows: “Where the Respondent intends to challenge an assessment served on him, he shall pay half of the assessed amount in an interest-yielding account of the Federal High Court, pending the determination of the application”. This and some other provisions of the said Practice Directions have attracted mixed reactions from Nigeria’s legal community as well as from stakeholders in the justice sector, tax law gurus and litigation giants.The present commentary is a preliminary part of my humble opinion on questions of legality, propriety or otherwise, arising specifically in respect of the provisions of Order V Rule 3 of the new Practice Directions.

With due respect, the prescription in Order V Rule 3 of the Practice Direction appears to be ultra vires the powers of the distinguished Chief Judge (CJ) of the Federal High Court (FHC), and therefore (I respectfully submit) may not stand in a court of law, if challenged, on grounds of oppressiveness, illegality and unconstitutionality. Meanwhile, I doubt some of the heads of our courts and their advisors truly appreciate the exact limitations of Practice Directions as a source of Civil or Criminal procedure. The way I see it (unless I am wrong; after all, I am not all-knowing), a Practice Direction does no more than provide guides on how to comply with existing Rules of Court (Rules made by the person issuing the Practice Direction), or on implementation of the rules or any aspect thereof. In UNILAG v AIGORO b(184) 11 SC 152 at 159, the Supreme Court of Nigeria defined Practice Direction as “a direction given by the appropriate authority stating the way and manner a particular rule of court should be complied with, observed or obeyed”. In Nwoko v. Nzekwo (2012) 12 NWLR (PT 1313 160 at 175, the Court of Appeal stated thus: “A Practice Direction is a written explanation or guideline on how to proceed in a particular area of law or court…. Practice Directions have the force of law and parties must adhere to it”. It could be seen from the above that a practice direction is merely a supplemental protocol to rules of civil and criminal procedure in the courts, a sort of device to regulate minor procedural matters on matters already provided for by existing Rules/law. (See: ;NAA v Okoro (1995) 7 SCNJ 292 at 301). Besides, some advisory pronouncements by courts of law, providing guides on practice and procedure have also been equated or described as Practice Directions (See Abubakar v Wada). See also Nwankwo v. Yar`adua (2010) 12 NWLR (Pt 1209) 518 to appreciate the status of Practice Direction in Election Cases as well as the effect of non-compliance therewith.

Although Practice Directions are treated as law or as having the force of law, they nevertheless come/rank last in the hierarchy of laws in Nigeria (SeeBuhari v. INEC* (2008) 19 NWLR (pt 1120) 236 at 341-342). Further, Practice Directions lack the capacity to establish a court or to make substantive provisions hitherto not provided in any law. Further, it’s doubtful if a Practice Direction can even make a new provision that is not already contained in an existing law. It’s obvious from the pronouncement of the Supreme Court in UNILAG v. AIGORO that a Practice Direction has no power to introduce a new provision not contained in the Rules; cannot introduce a provision inconsistent with the Rules (or with any law) and cannot give provisions or explanations on a new subject not contemplated by the Rules or other existing law.

Now, Order 57 of the Federal High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2019 contains provisions on powers of the Chief Judge of the Federal High Court to amend the Federal High Court (Civil Procedure) Rules, 2019, and to issue practice

directions “towards the realization of speedy, just and effective administration of justice”. The Order in its entirety, provides:”1. Whenever additional provisions are made to these Rules or any part thereof are amended or modified, the Chief Judge may issue directives for addition, publication or reprint of supplements to these Rules. 2. Whenever the Chief Judge makes amendment or modification to these Rules it shall be sufficient to publish same as supplemental provisions without the necessity of new body of Rules except when necessary. *3. The Chief Judge shall have the power to issue practice directions, protocols, directives and guidance towards the realization of speedy, just and effective administration of justice. Practice directions etc to be published.* 4. Such practice directions, protocols, directives and guidance shall be published and be given effect towards the realization of the fundamental objective of these Rules”.

From the above provisions, it’s doubtful there is any (enabling) legal justification for the Chief Judge (CJ) of the FHC to make such provisions as he is reported to have made in the Practice Direction presently under consideration. The powers of the CJ of the FHC to make Practice Directions is exercisable but only “towards the realization of speedy, just and effective administration of justice”. This is clear from the wording of Order 57 Rule 3 reportedly relied upon by His Lordship to issue the Federal High Court (Federal Inland Revenue Service) Practice Direction, 2021. Respectfully, it is difficult to see how the provision of Order V Rule 3 of the Practice Direction (requiring a person challenging a tax assessment imposed by the FIRS, to deposit 50 percent of the tax as assessed by the FIRS) can be reasonably described as a provision made “towards the realization of speedy, just and effective administration of justice”. Also doubtful is whether that particular provision (of Order V Rule 3) falls within the matters with respect to which the CJ of the FHC may make Practice Directions. Therefore (it’s respectfully so submitted), His Lordship lacks powers to make such a new or substantive provision in a Practice Direction.