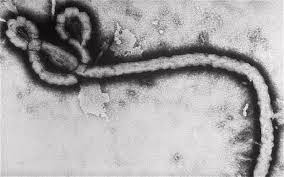

On 8 August 2014 the World Health Organisation

(WHO) categorised the Ebola outbreak in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia as a

Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

The potential impact of this epidemic is of interest to all

multinational corporations with a presence in Africa, and in particular to

those with projects, assets and personnel in those countries affected. The fact

that the WHO has only twice previously described an outbreak in these terms

underlies the severity of its impact, and potential impact, on construction

projects in West Africa.

On the date of the WHO’s announcement, a leading steel producer published

a press release noting that contractors undertaking expansion works at its

mines in Liberia had declared the outbreak a force majeure event and were

moving personnel out of the country. The company noted that it was assessing

the potential impact on the project schedule. This assessment will no doubt

involve a review of its key contracts and the impact of the outbreak on

completion dates and cost. A number of airlines have also cancelled flights to

West Africa, and several mining companies have cut back on nonessential travel

to the region.

Multinational

companies with interests in West Africa are implementing measures in order to

manage the impact on their businesses in the region and beyond. Our clients are

assessing potential exposure to the consequences of this outbreak and we

highlight below two critical contractual issues that parties must be aware of

in responding to this crisis.

Force majeure

There is no English common law doctrine of force majeure. Force

majeure is a principle borrowed from the French civil code, whereby a party

will not be liable for its failure to perform an obligation where this failure

has been caused by the occurrence of exceptional events outside that party’s

control. If there is no force majeure provision in your contract, you will need

to consider other remedies.

It follows that employers and contractors faced with a real or

potential impact from the Ebola outbreak will be asking themselves two high

level questions: 1) Does this event fit within the definition set out in my

particular contract or contracts?; and 2) Has (or will) the outbreak, as a

matter of fact, impacted (or will it impact) upon my performance or that of my

counterparty under the relevant agreement?

Interpretation of force majeure clauses

As noted

above, the English courts have been reluctant to set out a precise meaning of

the term ‘force majeure’. It follows that where the term is used in a contract;

the ordinary rules of contract interpretation are applicable, such that each

case will be different and turn on the particular words used in the contract.

This English law approach is different to civil law jurisdictions

in which the civil codes prescribe definitions of what is meant by force

majeure. As a result, English law construction/engineering contracts typically

contain an express definition of the phrase to avoid, insofar as it may be

possible, uncertainty and the potential for disputes.

Given the wide use of the FIDIC forms in international

construction projects, it is instructive to consider whether the Ebola outbreak

could be considered a force majeure event within the meaning of the relevant

FIDIC clause, and whether the outbreak would give rise to an entitlement for

additional time or money.

By way of example, Clause 19.1 of the FIDIC Red Book sets out a

broad definition of a force majeure event as

“…an exceptional event or circumstance:

a) which is beyond a Party’s control,

b) which such Party could not reasonably have provided against

before entering into the Contract,

c) which, having arisen, such Party could not reasonably have

avoided or overcome, and

d) which is not substantially attributable to the other Party.”

Provided an event satisfies the above conditions, then under FIDIC

it is a force majeure event (if Clause 19.1 is read in isolation).

The FIDIC Red Book then goes on to set out a non-exhaustive list

categories of examples for force majeure events, including war, rebellion,

riot, and natural catastrophes (such as earthquake, hurricane, typhoon or

volcanic activity).

Clause 19.1 does not expressly reference an epidemic as a force

majeure event (some forms of contract do), though that does not prevent it

being such an event. The critical question to determine whether or not an Ebola

outbreak is a force majeure event, is whether the four criteria set out above

have been satisfied.

There can

be little doubt that the Ebola outbreak is an event which is exceptional;

outside the control of commercial parties to a construction contract; could not

have been avoided/overcome once it arose; and is not substantially attributable

to either party. It would also be difficult to argue that a party to a

construction contract could have provided against the risk of an Ebola outbreak

before entering into the contract (though query whether or not such an outbreak

was foreseeable).

Entitlement to a force majeure event may well be very different in

circumstances where the relevant clause includes a requirement that the event

be unforeseeable (the FIDIC example does not). The element of foreseeability is

incorporated in Article 1148 of the French Civil Code, which stipulates that a

force majeure event must be unforeseeable, render performance impossible and be

outside of the control of the party invoking suspension of the relevant

contractual obligation. This is a higher threshold than that in FIDIC and we

have seen agreements where parties have agreed to allocate risk in this way.

Given that, in recent history and in certain parts of West Africa, there have

been Ebola outbreaks, albeit occasional and confined and not necessarily in the

countries currently affected, an Ebola outbreak may fall foul of a force

majeure provision that will not bite where an event is foreseeable.

In any event, under the FIDIC Red Book, a contractor would almost

certainly be entitled to obtain an extension of time in cases where it can

demonstrate delay affecting completion. This would, of course, be subject to

the time bar provisions found in Clause 19.2 relating to notice.

The question of an entitlement to additional cost (remembering

that cost is defined so as to exclude profit in FIDIC RED Book) arising from a

force majeure event is more complex. Clause 19.4 makes a distinction between

different kinds of force majeure events and where they occur. In fact, the

entitlement to cost refers back to the categories of force majeure events

listed in Clause 19.1. For example, an entitlement to additional cost will

accrue in the event that war and/or hostilities in a neighbouring country (or

indeed anywhere) effect the progress of the works. In contrast the balance of

the ‘categories’ of events listed in Clause 19.1 must occur in the country of

the works so as to qualify as a relief event and give rise to an entitlement to

costs.

An Ebola epidemic does not sit well in any of the categories

listed in Clause 19.1, thus creating an uncertainty in the drafting. Is there

an entitlement to an extension of time but no money? Further, if parties are

undertaking projects in adjoining countries, even if they are proximate to the

sites of the Ebola epidemic, does that preclude entitlement to cost?

Whilst the

drafting is unclear on this issue and there is no case-law on epidemics that

would provide useful guidance, the best interpretation of the contract when

read as a whole must be that there is an entitlement to an extension of time,

but not necessarily any cost.

Frustration – A Brief Refresher

Parties to contracts without an express risk allocation for

force-majeure-type events may need to consider alternative routes through which

to escape sanction/obtain relief. In such circumstances the English common law

doctrine of frustration may be invoked to provide some level of protection to

the party who would otherwise be in default.

A contract will be frustrated only in very limited circumstances,

where, for reasons attributable to none of the relevant parties, performance

has become impossible, illegal or would be totally different to what was

contemplated by the parties when the contract was formed.

It is difficult to imagine a scenario where it might be said that

the effects of the Ebola outbreak could not be mitigated through alternative

methods of performance (for example, procurement of raw materials from

alternate countries/sources unaffected by the outbreak, imposition of stringent

quarantine and medical controls and different techniques and policies to

protect the health and well-being of personnel on site). The English courts

have made it very clear that parties will not be entitled to relief from

performance for frustration merely when performance is rendered more difficult,

time-consuming or expensive.

Conclusion: The Contractual

Consequences of Ebola

In summary, the rights and obligations of employers and

contractors undertaking construction projects in West Africa will be determined

by a close reading of the provisions of the relevant contracts (and employing

modern means of interpreting contracts holistically). In many circumstances, we

consider it will be at least arguable that where an outbreak of Ebola has a

demonstrable effect on the progress of a project, it will qualify as a force

majeure event giving rise to an entitlement for time and/or monetary relief,

depending on the express terms of the relevant contract. It may also be the case

that in some civil law jurisdictions parties will be entitled to rely on the

provisions of the civil code in that country to obtain relief.

As the

leader of the Eversheds Africa Law Institute network, and with a presence in 32

African jurisdictions, including Liberia and Sierra Leone, Eversheds is

uniquely placed to assist construction clients across the region.

By: Paul Giles

Partner,

Eversheds LLP

0845 497 8680

paulgiles@eversheds.com

Julian Berenholtz

Senior

Associate, Eversheds LLP

0845 497 0767

Source:

legalweeklaw.com