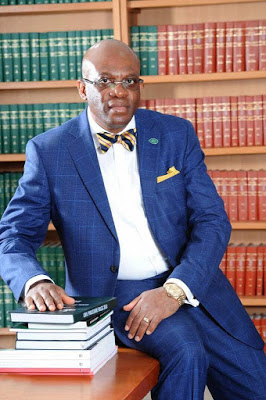

REFLECTIONS 6: WELFARE OF YOUNG LAWYERS AND RELATED ISSUES – PAUL USORO, SAN FCIArb

Related Issues (II): Mentorship

Without intending to downplay or diminish the need for reasonable remuneration and welfare packages for young lawyers, I believe that what young lawyers need the most is mentorship in law practice.

Mentorship, by the way, is not synonymous with pupillage. Pupillage, properly defined, is a mandatory pre-qualification process whereas mentorship is generally voluntary and without any defined and agreed pecuniary compensation for the mentor and/or mentee. Mentorship has no age-at-the-bar limit; it could benefit and be practiced by lawyers, no matter their ages at the Bar. The focus in this piece however is on mentorship for young lawyers. Mentorship requires the mentee to identify a role model in the profession, preferably, a successful practitioner who will guide and advise the mentee on the path to successful legal practice and also the ethics and traditions of the Bar and practice generally.

Most if not all successful practitioners have stories of their climb to the top of the profession, sometimes from rather humble beginnings. These stories, if shared with mentees, would help to dispel the notion that successful practitioners were all or mostly born into success and didn’t have to work for it. Depending on the level of relationship and trust, the mentor may share with the mentee the twist and turns of his personal experiences in the climb to the pinnacle of the profession and also the principles that guided and girded him to success. He could also give the mentee a peep, more importantly, into how he manages his success and the foundations for his remaining successful. Such a mentorship program could assist the mentee in handling difficult real-live legal situations and cases. It also comes in handy in equipping and advising the mentee on how to operate his own law practice and relate with clients and other justice sector stakeholders.

Most times, utmost patience and perseverance may be required of the mentees if the mentorship program must succeed and be rewarding. If the mentor is a busy successful practitioner, the demands on his time would be enormous and, despite his enthusiasm for the program, mentorship may not be in the upper rungs of his scale of priorities. It may also be worth the mentee’s time to study and know the mentor’s work schedule and, in particular, the times when the mentor may be free and/or receptive to calls from the mentee. The meetings between the mentor and the mentee do not have to always be formal settings; informal meetings, away from the office settings, may sometimes be very rewarding and relaxing for both parties.

I must enter a critical caveat here: mentorship programs can open doors for mentees, but they are not designed as door-openers. Some of us mistake mentorship for door-opening opportunities; mentorship is intended to provide practical guidance and advice to the mentee on legal practice, based on the experience and knowledge of the mentor. Introduction of prospective clients to mentees and facilitating the opening of doors isn’t part of mentoring; these may be add-ons benefits and, should not be bundled with the mentorship program. The mentee needs to understand that, the wealth of experience, knowledge and skills that the mentor may be willing to share with and impart to the mentee, if the mentee is patient, hard-working and ready to learn, could open innumerable doors and bring in premium clients for the mentee.

I believe that the NBA should encourage and actively facilitate such mentorship programs. A modified version of such program could involve periodic visits by young lawyers who are practicing in the hinterland to structured Law Firms in the cosmopolitan cities and branches to see and learn, first-hand, law office management and the practice of law in those Law Firms. It would be most beneficial to institutionalize a structured mentorship program for junior colleagues.