by Legalnaija | Apr 6, 2023 | Uncategorized

It can be generally agreed that following decades of football evolving from its 19th century origin days in Britain to the multi-million dollar empire it currently is, club football competitions now dominate the international football calendar. However, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) creates periodic exclusive windows for national football teams to play games via the International Window. This ensures that the relevance of international football between representative teams of national associations, which used to be the Holy Grail of football, is continually preserved.

An International Window is defined as a period of nine days starting on a Monday morning and ending on Tuesday night the following week (subject to temporary exceptions), which is reserved for national teams’ activities.[1] FIFA usually publishes the International Match Calendar for a period of between four and eight years after consultation with the relevant stakeholders. The International Match Calendar will include all International Windows available for the relevant period.

Many football fans will recall the President of the Italian football club S.S.C. Napoli, Aurelio De Laurentiis, throwing a tantrum a few months ago about no longer engaging the services of footballers who represent African nations, in view of the regular clash in calendar between the biennial African Cup of Nations (AFCON) tournament and important matches of the European Football season.[2] He reiterated his stance by threatening that he would only sign African players who agree to a clause in their contract prohibiting them from participating in the AFCON. However, what many do not know is that this was just an empty threat by the Naples executive, and any Sports Lawyer worth his/her salt would not include such clause in a football services contract. Where such clause is inserted in a contract, it would be null and void.

With international football matches returning to our screens last week for the first time since Argentina won the FIFA World Cup 2022, club football matches were halted about 2-3 days before the first round of international matches kicked off in the midweek of the week beginning on March 20, 2023. This is in line with the provisions of FIFA’s Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (“FSTP”), the last edition of which was published and released in October 2022.

The FSTP mandates football clubs to release their registered players to the national team of a country for which the player is eligible to play on the basis of her nationality if they are called up by the association concerned and prohibits any agreement between a player and his club to the contrary.[3] It is observed that in International Window weeks, elite club football matches are not played on Monday night as is usually done in most other weeks. This is because players must be released and start the travel to join their national team no later than Monday morning of the International Window week.[4]

It is mandatory that players be released for all International Windows listed in the International Match Calendar as well as for the final competitions of the FIFA World Cup, the FIFA Confederations Cup and each confederation’s periodic “A” grade championships.[5]

On the flip side, to also protect the interests of football clubs who in most cases pay the bulk of wages earned by players, FIFA limits the number of matches that may be played during any international window to a maximum of two matches by each national team (subject to temporary exceptions), irrespective of whether the matches are qualifying matches for an international tournament or friendlies. These matches can be scheduled any day as from Wednesday during the International Window week, provided that a minimum of two full calendar days are left between two matches (e.g. Thursday/Sunday or Saturday/Tuesday).[6]

As a further step to protecting the interests of football clubs, FIFA aims to reduce the total distance travelled by football players during the International Window. Thus, national teams are required to play the two matches within an International Window on the territory of the same confederation, with the only exception being intercontinental play-off matches. Also, if at least one of the two matches is a friendly, they can be played in two different confederations only if the distance between the venues does not exceed a total of five flight hours and two time-zones.[7]

Football clubs are not obliged to release players outside an international window or outside the final competitions included in the international match calendar. Similarly, it is not compulsory to release the same player for more than one “A” representative team final competition per year.[8]

As another means of protecting the interests of football clubs, players must also start the travel back to their club no later than the next Wednesday morning following the end of the international window, subject to temporary exception allowed by FIFA.[9] As regards this particular provision, the clubs and associations concerned may agree a longer period of release or different arrangements.[10] A player resuming duty with their clubs after an International Window must resume no later than 24 hours after the end of the period for which they had to be released, or 48 hours if the national teams’ activities took place in a different confederation to the one in which the player’s club is registered.[11]

Where a player does not resume as stated above, the Players’ Status Chamber of the Football Tribunal may, at the request of the Club:

- a) issue a fine;

- b) reduce the affected player’s period of release for the next International Window; or

- c) ban the association from calling up the player(s) for subsequent national-team activities.[12]

Given the need to protect the economic interests of football clubs in football players while ensuring that international football matches are taken seriously by clubs and players alike, FIFA’s fine balancing act of laying down precise regulations that address the interest of all parties involved is impressive.

[1] Article 1, para 4, Annexe 1, Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players, October 2022

[2] https://www.goal.com/en-ng/news/napoli-de-laurentiis-african-players-afcon/blt0f8dc87fa7999bd3

[3] Article 1, para 1, Annexe 1, RSTP

[4] Article 1, para 7, Annexe 1, RSTP

[5] Article 1, para 2, Annexe 1, RSTP

[6] Article 1, para 4, Annexe 1, RSTP

[7] Article 1, para 5, Annexe 1, RSTP

[8] Article 1, para 6, Annexe 1, RSTP

[9] Article 1, para 7, Annexe 1, RSTP

[10] Article 1, para 8, Annexe 1, RSTP

[11] Article 1, para 9, Annexe 1, RSTP

[12] Article 1, paras 10 & 11, Annexe 1, RSTP

by Legalnaija | Mar 7, 2023 | Uncategorized

Great News For Law Firms In Nigeria

We have some amazing news.

Law firms can now register and subscribe to the Legalnaija Directory for lawyers and law firms.

Our Directory is Nigeria’s fastest growing market place for lawyers and law firms looking to establish their reputations and brands. The Directory also allows Users find your law firm through your area of expertise and location.

Take advantage of this amazing opportunity to grow your legal practice. In addition you also get free access to customizable Agreement templates, law books and materials, and a platform to showcase your legal articles, content and expertise.

Don’t loose the opportunity to make your law practice stand out from others and be more accessible to the high number of users searching the internet for legal solutions.

Follow this link to register https://app.legalnaija.com/signup, and if you need to contact support, please mail hello@legalnaija.com

Check out the Directory here https://app.legalnaija.com

@Legalnaija

by Legalnaija | Feb 24, 2023 | Uncategorized

Due Diligence (DD) Exercises (“DD Exercise(s)”) are essential to commercial transactions. The conduct of a DD Exercise is a continuous process right from when a transaction is conceived, discussed with the advisers up to the end of the deal. There are different types of DD which include financial due diligence, tax due diligence, commercial due diligence, technical due diligence, and legal due diligence. The legal due diligence involves reviewing documents that define a party’s ability to fulfil its obligation in a transaction, identify the inherent risks, assess the risks, propose risk management measures to help the transaction bankable. Therefore, a DD Exercise must be factual, analytical, and structured. Often, a DD is adopted in acquisition, investment, and finance transactions.

A DD Exercise could be conducted on the company, shareholders, and assets of the Company. This article summarizes some of the key considerations in conducting a DD Exercise for assets/shares acquisition. In a DD Exercise, usually, the investor or buyer (the “Acquirer”) interested in buying assets/shares in a target company (the “Target” or “Seller”) is primarily responsible for carrying out a DD exercise.

A DD Exercise would involve a review of documents uploaded to a Virtual Data Room (VDR) and sometimes, physical visits to the offices of applicable regulatory authorities in the transaction. The process of a DD Exercise commences with preparing a DD checklist which lists the necessary information the Acquirer need from the Target or Seller. Upon the upload of the requisite information to the VDR, a Due Diligence Report (“DD Report”), which contains detailed information on the Target, is drawn up. A DD Report sets out, in detail, the necessary information and issues to consider.

The essence of a DD Exercise includes the following:

- It gives the Acquirer a better understanding of the Target/Seller.

- It helps professional advisers understand the actual state of affairs of the Target /Seller

- It helps to identify risks and how to mitigate those risks. Identifying the risks helps in the valuation of the Target/Seller to determine a practical purchase price. The greater the risks, the greater the likely discount to be sought by the Acquirer.

- It helps to determine the suitable structure for the proposed transaction. .

- It helps the parties in allocating risks in the representations and warranties.

Notably, the questions in a DD checklist vary depending on whether it is an asset or shares acquisition. Specifically, for an asset acquisition, general questions to be asked during a DD Exercise include the following:

- Title of the Target in the assets. This helps to determine whether the Target has a valid title to the asset, if the title is subject to a limited duration, or conditions and any encumbrances on the title.

- Whether there are existing, pending, contingent and threatened litigation(s) concerning the assets;

- The material contracts concerning the assets (such as the joint operating agreements, gas sale and purchase agreements, and production sharing contracts in the energy and power sector)

- Regulatory Compliance, licenses, approvals or permits (like environmental permits) required to operate the assets.

- Third-party approval and consents required to create or transfer any interest in the assets.

- The physical condition of the assets, where applicable.

For shares acquisition in a company, general questions to be asked during a DD Exercise include the following:

- General corporate information such as constitutional documents of the Target and details of shareholders and directors.

- Details of material contracts such as shareholders’ agreements.

- Finance, Banking facilities and Indebtedness status such as existing charges, mortgages and debentures.

- Regulatory Compliance, such as licenses, permits and approvals required for the Target operation, has been obtained from the relevant regulatory authorities. Regulatory Compliance also ensures that appropriate filings and returns have been done and the Target has what is statutorily required to operate as a legal entity in the country.

- Taxation like companies’ income tax

- Labour and Employment

- Intellectual Property.

- Real Estate.

- Insurance.

- Material claims and litigation.

As earlier stated, apart from legal DD Exercise, it is not uncommon for DD Exercise to be carried out by other professional advisors like financial and technical advisers. Thus, financial due diligence is carried out to assess the Target’s relevant financial statements, balance sheets, business plans, feasibility studies, and cash flow statements. Financial due diligence helps to prevent a transaction from being a sinkhole at the end of the day. Technical due diligence is also carried out, particularly for energy investment, to assess the proximity of the energy source, the availability of needed machinery and plants, the availability of skilled workforce, the technology used, the civil and electrical design, the status of permits, licenses, and authorizations, visits to operating plants or sites, audits of equipment manufacturers, monitoring of asset construction, among other things.

DD Report

Upon completing the DD Exercise (reviewing all uploaded documents in the VDR, enquiries/visits to the regulatory authorities and noting all necessary information), a DD Report is drafted. A DD report is the finalized report of the meticulous investigation and review process that characterizes the DD Exercise. It is meant to provide an as-is analysis of Target’s assets or the state of affairs of the Target. The DD report will include all necessary facts discovered during the DD Exercise and will proffer solutions to identified issues and how the transaction can be best structured.

A DD report should commence with an executive summary (which contains critical findings of the DD Exercise), and it is followed by succeeding paragraphs addressing each subject matter in the DD exercise (such as title, material contracts, litigations, insurance, intellectual property rights, general corporate matters, taxation).

Notwithstanding how thorough a DD exercise can be, some risks may not be identified during the DD Exercise. This omission could be due to inadvertence by the Acquirer, considering the large volumes of information and documentation involved during DD Exercise or wilful concealment by the Target. Thus, to guard against any error that might have occurred, the purchase agreements (of the shares or assets) will contain representations and warranties issued by the Target to the Acquirer and indemnity clauses by the Target or Seller to indemnify the Acquirer for any losses that may arise where the representations and warranties are incorrect. Usually, the representations and warranties include:

- The Target or Seller has a title to the assets/share, and the title is not encumbered.

- The Target is valid, incorporated, and existing under relevant laws.

- The Target has obtained necessary government permits, approvals, and licenses to operate the asset and they are valid and subsisting.

- That there are no existing, threatened and pending material litigation or governmental investigation against the assets and the Target.

- That all necessary taxes and royalties have been duly paid.

- That there it is in compliance with necessary environmental, health and safety regulations.

- That all material contracts necessary to the transaction have been disclosed, and there is no breach/default under the disclosed agreements.

Conclusion

DD Exercises are crucial to the success of any transaction/acquisition/investment. Therefore, DD Exercises must be carried out thoroughly and extensively, bearing in mind the commercials and innovative ways to mitigate identified risks.

I hope you find this educating. Thank you!

Iyanujesu is a first-class graduate (among the top 30 (0.6%) out of 5,689 students) from the Nigerian Law School. She is an associate in a leading commercial law firm in Lagos, Nigeria, where she advises energy companies on different aspects to project structuring, development, and financing. She advises clients in different sectors on corporate, commercial, oil and gas, mergers and acquisitions, financing, power, infrastructure, and capital markets. She is skilled in legal advisory, regulatory compliance, contract negotiation, research, and writing. She advocates leadership, volunteering, and teamwork. She has to her name several leadership and entrepreneurial awards. She enjoys writing, and she has an academic blog where she writes on commercial issues- https://medium.com/@iyanujesu.oguntunji .

Iyanujesu is a first-class graduate (among the top 30 (0.6%) out of 5,689 students) from the Nigerian Law School. She is an associate in a leading commercial law firm in Lagos, Nigeria, where she advises energy companies on different aspects to project structuring, development, and financing. She advises clients in different sectors on corporate, commercial, oil and gas, mergers and acquisitions, financing, power, infrastructure, and capital markets. She is skilled in legal advisory, regulatory compliance, contract negotiation, research, and writing. She advocates leadership, volunteering, and teamwork. She has to her name several leadership and entrepreneurial awards. She enjoys writing, and she has an academic blog where she writes on commercial issues- https://medium.com/@iyanujesu.oguntunji .

by Legalnaija | Feb 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

Introduction:

Despite the numerous advantages of Arbitration and ADR to the global economy, Nigeria has steadily witnessed a slow-paced development in the settlement of commercial disputes through arbitration and other ADR mechanisms, majority of the Multinational companies with huge transactions and high-profile Commercial disputes have continually made foreign countries the venue and seat of Arbitration. Numerous Arbitral proceedings are conducted outside Nigeria even though the commercial disputes occurred in Nigeria. Unfortunately, this has led to low patronage of Nigerian Arbitrators and the increasing volume of arbitrable disputes in Nigeria has not translated into many businesses for Nigerian Arbitrators.

In a bid to foster the growth of arbitration in Nigeria, Numerous legal luminaries have urged businesses and legal practitioners to make Nigeria the seat and venue of arbitration especially where the subject-matter of the dispute is connected to Nigeria. At the 2022 Annual Conference of the Nigerian Institute of Chartered Arbitrators (NICArb), The Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice, Abubakar Malami, SAN noted that making Nigeria the seat and venue of Arbitration in commercial agreements would enhance foreign direct investment and further boost the Country’s economy.

While some persons have attributed these concerns to the lack of confidence in Nigerian Arbitrators, it is pertinent to state that there are other reasons why this menace exists.

The major reasons why Multinational Companies do not make Nigeria the seat and venue of Arbitration are:

- The ease with which arbitral agreements and awards are dismissed by Nigerian Courts on ground of technicalities;

A classic example of this discouraging circumstance is the decision of the Court of appeal in Mekwunye v. Imoukhuede, it took the intervention of the supreme court to overturn this decision and despite the Supreme court’s decision, it took 12 years between 2007 when the arbitral award was made and 2019 when the Supreme Court finally laid the matter to rest.

In Mekwunye’s case (supra), the Court of Appeal had indeed set aside the Arbitral award based on a minor error on the executed agreement; the arbitration clause had wrongly referred to the appointing authority as “Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, London, Nigeria Branch,” instead of “Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, UK, Nigeria Branch”. The Court of appeal dismissed the arbitration agreement and the arbitral award on the ground that the name of appointing authority was wrongly written. This decision brought distrust and uncertainties to the future of commercial arbitration in Nigeria as no Company would want to have its commercial disputes resolved in a country where judicial intervention is capable of setting aside an arbitral award at any cost on the ground of technicalities.

2. Delays and bottlenecks in enforcement of arbitral awards and appeals;

Even though the 2018 World Bank index on ease of doing business ranked Nigeria as 96th in enforcement of contract and stated that it takes about 454 days to enforce a contract through the court, The length and stress involved in enforcement of arbitral awards in Nigeria is not entirely pleasant for commercial activities as profits from arbitral awards may remain inaccessible for a long time due to the number of days involved before enforcement is achieved. Aside from the long duration in enforcement of arbitral awards, another major challenge is the duration of appeals; appeals may be pending for 8 to 10 years if taken from the High Court to the Supreme Court.

In providing a solution to this menace, The Nigerian Institute of Chartered Arbitrators (NICArb) has suggested that specialized commercial courts be established to tackle the delays in enforcement of arbitral awards. It is also suggested that the leave of Court should first be sought and obtained before an application to challenge an arbitral award or an appeal against the enforcement of an award is brought before the court.

3. long overdue laws which do not embrace recent global trends in International Commercial Arbitration;

The principal enactment governing the practice of Arbitration in Nigeria is the Arbitration and Conciliation Act which was enacted in 1988 and now long overdue for a change. There are numerous 21st century advancements which are not yet applicable in Nigeria due to delays in enactment of a new Arbitration and Mediation Act. The National Assembly has passed a bill known as the Arbitration and Mediation Bill 2022 (the “Bill”), The Bill represents a significant upgrade from its predecessor but unfortunately the bill is still awaiting Presidential Assent since 10th of May 2022.

In conclusion, there is need to develop a national policy on Arbitration, ensuring that trades and contracts executed in Nigeria had embedded in them an Arbitration clause which makes Nigeria the venue and seat of Arbitration and thereby promoting job creation and economic growth. As a full or part-time Arbitrator, what is key is having jobs or services to render. Nigerians get trained in ADR and Arbitration with the hope that they will make a viable career and also mke a living. Unfortunately, they are faced with a lack of opportunities to practice the skills.

References:

- Suit No. SC/851/2014: Dr. Charles Mekwunye V Christian Imoukhuede (Judgment delivered on 7th of June 2019)

- Olubayo Oluduro, PhD (Ghent), FCArb. & Akin Olawale Oluwadayisi, Ph.D. (Ilorin) (2021) Journal on Arbitration volume 16 Number 1 ISSN: 2021-957x pp. 1-165

- https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2022/11/29/malami-suggests-nigeria-as-seat-of-arbitration/

- https://brooksandknights.com/2020/05/07/revamping-the-arbitration-process-in-nigeria-in-ensuring-speedy-resolution-of-commercial-disputes-a-consideration-of-the-case-of-mekwunye-v-imoukhuede/

- https://www.mondaq.com/nigeria/court-procedure/767768/enforcement-of-arbitral-awards

- https://businessday.ng/news/article/nicarb-recommends-specialized-courts-to-alleviate-delays-in-enforcing-arbitral-awards/

- Oladimeji Ramon, Nigerian Arbitrators Battle Job Loss to Foreigners (punch, 1 November 2018) https://punchng.com/nigerian-arbitrators-battle-job-loss-to-foreigners/

- https://thenigerialawyer.com/how-arbitration-and-adr-can-become-an-additional-career-for-all-professionals/

- Urska Velikonja, ‘Making Peace and Making Money: Economic Analysis of the Market for Mediators in private practice,’ 72 (2009) Albany Law Review, 257-291 at 271

Oni Oluwatoyin Bamidele (Jurist O’toyin)

onioluwatoyinbamidele@gmail.com

by Legalnaija | Feb 5, 2023 | Uncategorized

Loving a lawyer can be an amazing experience, not only are you with a very smart, talented and intelligent person but you know they definitively also have style.

If you have a lawyer Bae, here a few tips on how you can show them you love them this valentine.

1. Support their law practice by referring clients to them.

2. Buy them books in their area of practice, you can find law books here legalnaija.com/shop plus you get a 15% discount when you use the Voucher Code: ILOVELAWYERS

3. Don’t stress a lawyer, they are already dealing with a lot at work so don’t add to that.

4. Get your facts/ stories right because lawyers deal with a lot two-time double dealers in the course of their work, so they will spot any inconsistencies in your statements, and you don’t want them to grill you like an hostile witness.

5. Give them space for work and understand their jobs are very important.

6. Be patient with them. Lawyers are thinkers, and their minds never stop working, so dating them requires communication, understanding, and patience.

If you have at more tips for anyone dating a lawyer, drop them below this tweet.

@Legalnaija

by Legalnaija | Feb 3, 2023 | Uncategorized

15 Electoral Laws All Nigerians Should Know | Legalnaija

On the 25th day of February, 2022, the President signed the Electoral Bill into law. The new enactment has thus effectively repealed the old Electoral Act of 2010. Essentially, this article provides an insight into 15 electoral laws that all Nigerians are expected to know.

1. Primary Elections and Submission of Candidates Names to INEC

Pursuant to section 29(1) of the Electoral Act, 2022, political parties are expected to conduct their primaries and also submit candidate’s list to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) not later than 180 days before the date fixed for general election. Meanwhile, the old Act permitted the submission of list of candidates not later than 60 days before the conduct of the general election. This means that primaries and submission of list of candidates must done on time; within the stipulated time frame.

2. Early Campaigns

Noteworthy, section 94 of the Act stipulates that all campaigns should commence 150 days before polling day and end 24 hours before that day. Formerly, the time frame was 90 days before the day of election.

3. Bribery and Vote Buying

There are certain provisions of the Electoral Act that prohibit bribery and vote buying. For instance, section 90(1) provides that a political party shall not accept or keep any anonymous monetary or other contributions, gift, or property, from any source. Giving bribe to electoral officers in order to procure the return of a candidate is a crime which is punishable with a fine of N500,000 or imprisonment for a term of 12 months or both. It is also an offence with similar punishment to give bribe to voters to cast their vote in favour of a particular candidate.

4. Free and Fair Election

In order to ensure free and fair election, section 126 prohibits any person from persuading other voters to vote for a particular candidate on the election day. Furthermore, it frowns at anyone who shouts slogans concerning the election or intimidate voters during the election. No symbol, photograph or vehicle shall be used to promote any political party on the day of election. Specifically, section 126(1)(j) prohibits snatching or destroying of any election materials.

5. Qualifications for Registration as a Voter

Before a person can be qualified to register as a Voter, the following requirements in section 12(1) must be met. First, the person must be a citizen of Nigeria. Second, the person must have attained the age of 18 years. Third, the person must be resident, work in, or originate from the Local Government Area Council or Ward where the registration centre is located. The fourth requirement is that such a person must present himself or herself to the registration officers as a voter. Lastly, the person must not be subject to any legal incapacity to vote under any law, rule or regulation in force in NigeNigeria.

6. Double Registration is Illegal

Section 12(2) prohibits double registration. Section 12(3) imposes a fine of not more than N100,000 or imprisonment for a term of not more one year or both for anyone who registers more than once.

7. Impersonation of Voters

The express wording of section 119(1)(a) prevents any person from impersonating a living, or dead or a fictitious person at the time of voting. This act attracts a maximum fine of N500,000 or imprisonment for a term of 12 months or both. Anyone who aids or abets the impersonator would also bear a similar punishment.

8. Secrecy in Voting

Section 122 provides that voting shall be done in secret at the polling unit. It also provides that no person shall communicate to any person information as to the name or number on the register of any voter who has or has not voted at the polling unit. It further prohibits unnecessary or unjustified interference with the voting process. Failure to comply with these provisions would render the perpetrator liable to a maximum fine of N100,000 or imprisonment for a term of three months or both. Significantly, section 144 reinforces secrecy of ballot by providing that no person who has voted in any election shall be required to say for whom he or she voted in any legal proceedings.

9. Replacement of Lost or Damages Voter’s Card

Section 18 allows a voter to apply to the electoral officer, not less than 90 days before the polling day, for a replacement of voter’s card that is lost, destroyed, defaced, torn or otherwise damaged. If the electoral officer is satisfied with the application, a new voter’s card would be issued with the word “REPLACEMENT” clearly marked or printed on it, together with the date it was issued.

10. Buying and Selling Voter’s Card is Illegal

According to section 22 of the Act, it is unlawful for a person to sell or attempt to sell or offer for sale any voter’s card whether belonging to him/her or to another person. This also applies to anyone who buys or offers to buy any voter’s card for himself/herself or for another person. The punishment for the offence is a fine not more than N500,000 or imprisonment not more than two years or both.

11. Personal Voting

According to section 55, each voter is expected to record his or her vote at the polling unit or voting centre personally in accordance with the manner prescribed by the Commission.

12. Persons with Disabilities and Special Needs

Section 54(1) of the Act allows a person to assist a voter with visual impairment or any other form of disability. Such a person is allowed to accompany the disabled person into the voting compartment so as to help him or her to vote for their preferred candidate. To make it easy for disabled persons to vote, the Commission is mandated to make the following facilities available at the polling place: Braille, large embossed print, electronic devices, sign language interpretation and off-site voting.

13. Review of electoral results declared under duress

Section 65(1) of the Act empowers INEC to review electoral results which, in the opinion of the Commission, was declared involuntarily. This review is expected to be done with seven days from the date in which the results were declared.

14. Non-Partisanship or Neutrality

Section 8(5) of the Act requires INEC officials to maintain political neutrality. This means that an INEC official cannot be a politician or a member of a political party at the same time. It is also important to state that it is an offence for any INEC official to be affiliated with any political party. Such offence is punishable with a fine of N5,000,000 or an imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years or both.

15. E-Voting and Transmission of Results

By virtue of sections 47 and 50(2) of the Act, INEC is authorised to use smart card readers, electronic accreditation of voters amongst others. Furthermore, INEC can transmit results through electronic platforms. Section 62(2) empowers the Commission to maintain a centralized electronic register of election for e-collation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clifford Ndujihe, ’10 Key Provisions of the New Electoral Act’ Vanguardng (25 February, 2022) https://www.vanguardngr.com/2022/02/10-key-provisions-of-the-new-electoral-act/amp/ accessed 26 December 2022.

David Ijaseun, ‘2022 Electoral Bill: 10 things every Nigerian should know’ Businessdayng (22 February 2022) <https://businessday.ng/politics/article/electoral-bill-2022-10-things-every-nigerian-should-know /> accessed 26 December 2022.

Jide Ojo, ‘Anti-corruption provisions in Nigeria’s Electoral Laws’ Punchng (18 March 2022) https://punchng.com/anti-corruption-provisions-in-nigerias-electoral-laws/?amp accessed 26 December 2022

Jude Otakpor, ‘Nigeria: Some Distinctive Features Of Nigeria’s Electoral Act, 2022’ Mondaq (26 April 2022) https://www.mondaq.com/nigeria/constitutional-administrative-law/1186800/some-distinctive-features-of-nigeria39s-electoral-act-2022 accessed 26 December 2022.

@Legalnaija

www.legalnaija.com

Hello@legalnaija.com

by Legalnaija | Feb 3, 2023 | Uncategorized

Fifa’s Football Agent Regulations 2022 – AN APPRAISAL | Oluwajoba Odefemi[1]

On December 16, 2022, one day before Croatia played Morocco in the third-place playoffs at the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, and two days before Argentina beat France in that epic final to win the competition, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) Council at its meeting in Doha ratified a new regulation regime to govern the activities of football agents, called the FIFA Football Agent Regulations (“FFAR/the Regulations”)

On January 9, 2023, the Regulations – which FIFA says will guarantee minimum professional and ethical standards for the occupation of football agent, including a mandatory licensing system – came into force. The new regime replaced the erstwhile FIFA Regulations on Working with Intermediaries (“the Intermediary Regulations”), which came into force on 1 April 2015, and which had previously de-centralised the regulation of such intermediaries.

While the FFAR may not be all good news for some of the existing persons who serve as football agents given some of the restrictions it has introduced, it is one of the more anticipated developments by football stakeholders in the last few years in view of its potential to bring more professionalism to football agency, as well as ensure organisation in an otherwise chaotic sector of the football world.

Among the core objectives of FIFA’s introduction of the new football agency regime are to ensure the quality of the service provided by football agents to clientsare fair and reasonable, limiting conflicts of interest,protecting players who lack experience or information relating to thefootball transfer system and preventing exploitative and excessive practices.[2]

The Regulations govern the occupation of football agents involved in theinternational transfer system, and particularly apply to representation agreements with an international dimension or connected to an international transfer or transaction.[3]Thus, for example, where there is a transfer of football players between a football club in Nigeria’s Professional Football League (first tier) and another football club in Nigeria’s Nationwide League One (third tier), the football agents involved in that transaction will not be governed by the Regulations. Each member association is required to implement and enforce its own national football agentregulations (which must be consistent with the FFAR) by 30 September 2023, which will govern the occupation of footballagents within their respective territory.[4]

A – Z of Sports Law & Business

Under the new regulations, to engage in the business of football agent services, prospective football agents will need a football agent licence issued by FIFA.To be issued a football agent licence, an applicant mustsuccessfully pass the exam conducted by FIFA, comply with the eligibility requirements and pay an annual licence fee to FIFA.[5]

It is worthy to note that a football agent licence can only be issued to a natural person, is strictly personal and non-transferable and authorizes agents to provide services to football players, coaches and clubs on a worldwide basis.[6] Licensed football agents are required to comply with continuing professional development requirements on an annual basis.[7]

Given the above, football players who are currently represented by family members (think Lionel Messi, Neymar, et al) who have no special qualifications to operate as FIFA licensed agents will be required to comply with the provisions of the FFAR.

Furthermore, a football agent may only perform football agent services for a client after entering into a written Representation Agreement with that client, and the maximum term for any such agreement with an individual is two (2) years[8].

However, Representation Agreements between football players/clubs and agents in existence prior to December 16, 2022, although not compliant with the requirements of the FFAR, will remain valid until their natural expiration date as is currently contained in the contract.

Also, agents registered before 2015 (under FIFA’s oldlicensing regimesof 1991, 1995, 2001 or 2008) will not have to take the new exam as they qualified under the old rules.[9]

Multiple representation by a single agent to different parties in a single transaction has been limited. This ensures that conflict of interest is avoided. Thus, under the new football agent regime, a football agent can no longer perform football agent services for all parties within the same transaction, both a releasing entity and individual in a transaction, or both a releasing entity (selling club) and engaging entity (buying club)in a transaction. The only permitted exception for dual representation is represent both an individual and an engaging entity in the same transaction, and this is subject to prior explicit writtenconsent being given by both clients.[10]

Another innovation of the FFAR is the enforcement of a cap on the amount chargeable by agents as service fee. Under the Intermediary Regulations, the cap was merely a recommendation. [11]Agents representing individuals or an engaging entity can now charge a maximum of 3% of the individual’s remuneration where the individual’s annual remuneration is above USD200,000 (Two Hundred Thousand United States Dollars).

Where an agent represents both an individual and the engaging entity in a single transaction (as apermitted dual representation), the maximum service fee chargeable is 6% of the individual’s remuneration where the individual’s annual remuneration is above USD200,000 (Two Hundred Thousand United States Dollars).However, where an agent represents the releasing entity, the maximum service fee chargeable on an annual remuneration above USD200,000 (Two Hundred Thousand United States Dollars) is 10% of the remuneration.[12]It is worthy to note that if an individual’s remuneration is above USD200,000, the 3% and 6% limits only apply to the amount in excess of USD200,000.

The aim of the cap on agent fees seems to be to arrest the excesses of a few agentswho are wont to exploiting their clients’ moves from club to club to maximize their gains (Man United fans will be familiar with the reported earnings of late football agent Mini Raiola on transactions involving Paul Pogba). The question remains whether such blanket cap is not unfair and limiting on the freedom of service professionals to charge in line with their level of expertise.

Agents are also barred from approaching clients in solicitation where such client is bound by an exclusive RepresentationAgreement with another football agent, except in the final two monthsof that exclusive Representation Agreement, and may not enter into a RepresentationAgreement with such client except in the final two months of that exclusive RepresentationAgreement.[13]

Finally, the Regulations aim to protect minors by stipulating that football agents may not approach minors or their legal guardians earlier than six months before they become eligible to sign their first professional contract, and any approach made within the six months window must be made only afterwritten consent has been obtained from the minor’s legal guardian.[14] For example, in territories where football players are allowed to sign their first professional contract at 17, no approach must be made or Representation Agreement signed before a football player is 16 ½ years, while for territories where the qualifying age is 18, such approach must not come before a player is 17 ½ years.

The FFAR came into force on Monday, 9 January 2023, although there is provision for a transition period ahead of the obligation to only use licensed football agents and the cap on agent fees, which begins on 1 October 2023.

FIFA aims to ensure compliance with the requirement of the FFAR by requiring that all relevant transfer or employment agreement in a transaction contain the football agent’s name, their client, their FIFA licence number and theirsignature. Nonetheless, transactions may still be negotiated and concluded without the services of an agent at all, in which case, this is to be explicitly stated in the relevanttransfer or employment agreement.[15]

All in all, the new regime should bring greater control to the activities of football agents and ensure that rogue agents find it difficult to exploit clients, particularly football players who have little leverage in negotiations.

[1]Oluwajoba is a Legal Practitioner based in Lagos,with specialization in Corporate Commercial Law, Regulations and Compliance. He is also a licensed Football Referee and Sports Law enthusiast.

[2]Article 1 (2), FFAR

[3]Article 2 (1), FFAR

[4]Article 3 (1), FFAR

[5]Article 4 and 5, FFAR

[6]Article 8, FFAR

[7]Article 9, FFAR

[8]Article 12 (3), FFAR

[9]Article 23, FFAR

[10]Article 12 (8& 9), FFAR

[11]Article 7 (3), Intermediary Regulations

[12]Article 15, FFAR

[13]Article 16 (1), FFAR

[14]Article 13, FFAR

[15]Article 12 (11 & 12), FFAR

by Legalnaija | Jan 24, 2023 | Uncategorized

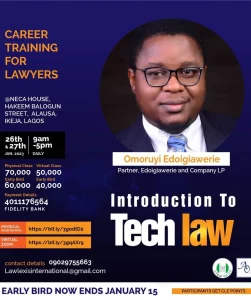

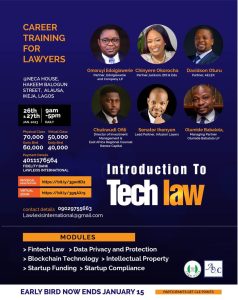

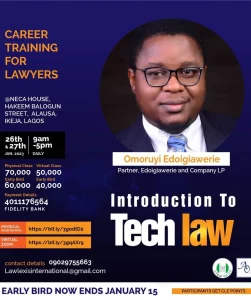

OMORUYI OSAGIE EDOIGIAWERIE

@uyilaw is the Founder and Lead Partner of the Firm. He also leads the Corporate Commercial, Tech and specialised team at the Firm. He specializes and has in-depth experience in Startup Law, Corporate Commercial Legal Practice, Statutory Compliance and Entrepreneurship and other corporate commercial practice areas.

He also has expert knowledge of Matrimonial Causes and Entertainment Law and expertly provides legal advisory and capacity building support to a broad spectrum of clients locally and internationally. Omoruyi has advised on several landmark and strategic transactions both locally and internationally. So far, he has helped build and grow over 1000 companies most of who remain gainfully in business and still rely on him for expert legal advice.

He is a member of the Nigeria Bar Association and the American Bar Association. In addition, he is a Startup Mentor at the Tony Elumelu Foundation. In the Nigerian Bar Association, he was appointed a member of Mentoring Committee of the Nigeria Bar Association, Secretary of the Steering Committee of the Young Members Group of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (UK) Nigerian Branch and member of the policy and drafting team at the Nigerian Startup Act Project. Omoruyi is a Harvard trained Leadership Expert, Yale Certified Business Negotiator and Business Compliance Specialist. He also holds a specialization in Legal Entrepreneurship from the University of Maryland, USA and a compliance and data protection certification from the University of Pensylvania. A prolific writer, Omoruyi is the author of the best-selling masterpiece for entrepreneurs, The Business Of Running Your Business To Building A Successful Business; A Practical Guide the book is a product of his in-depth experience in Corporate and Commercial Legal Practice, Statutory Compliance Matters, and Entrepreneurship Development.

He is also recognized as one of the leading Entrepreneurship and Startup lawyers in Nigeria. Omoruyi regularly contributes to nation building through regular speaking engagements across the Country on contemporary issues that relate to law, and nation building.

by Legalnaija | Jan 23, 2023 | Uncategorized

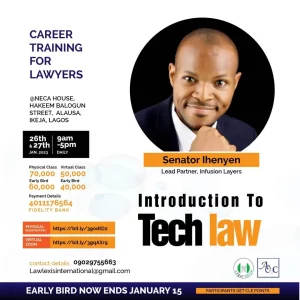

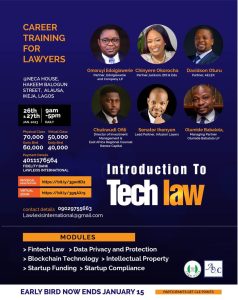

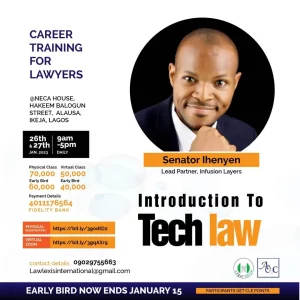

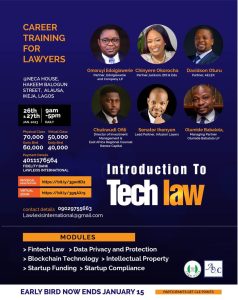

Senator Ihenyen is the Lead Partner at Infusion Lawyers where he heads the FinTech, Blockchain & Virtual Assets Practice of the law firm. He has advised both local and global companies, including FinTech companies on various areas of law, policy, and regulations, which includes FinTech, blockchain, data protection & privacy, and related areas of information technology.

A tech lawyer with interest in policy and regulations, Senator is former President of Stakeholders in Blockchain Technology Association of Nigeria (SiBAN) where he is now a member of the Advisory Council. He served as Vice Chairman, Policy & Regulations. Senator is also the current General Secretary of the Blockchain Industry Coordinating Committee of Nigeria (BICCoN), the coordinating body in Nigeria’s emerging blockchain industry. He is also the current General Secretary of the FinTech Alliance Coordinating Team (FACT), comprising the Fintech Association of Nigeria (FinTechNGR), Blockchain Nigeria User Group (BNUG), Cryptography Development Initiative of Nigeria (CDIN), Innovation Support Network Hubs (ISN Hubs), and Financial Services Innovators (FSI).

Senator is the exclusive contributor (Nigeria chapter) to the International Guide to Blockchain 2020 and Lead Trainer, Blockchain for Lawyers 101. A contributor (Nigeria Chapter) to the International Comparative Legal Guide to Data Protection 2019, Senator also advises on data protection and privacy. He has been the author of the Data Protection Overview for Nigeria on DataGuidance by OneTrust since 2016.

Senator has been a resource person and speaker on FinTech, blockchain, and innovation at various fora, including the Committee of Chief Information Security Officers of Nigerian Financial Institutions (CCISONFI) Conference, May 2021; Blockchain Nigeria User Group Conference, May 2018; Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Forensics for the Economic and Financial Crimes (EFCC), September 2021; Blockchain & Fintech 101, Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), Asaba Branch Law Week, December 2021; Legal Business Conference on ‘Regulating Blockchain, FinTech, and Innovations’, 17 May 2022; TechPoint Africa Blockchain Summit (TABS), 20 May 2022; and ‘Evolving Relationship between FinTech, Regulators, and Financial Institutions’, Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), June 2022.

Senator is currently the 1st Vice Chairman, Intellectual Property Committee and member of the Information Technology Committee of the Nigeria Bar Association Section on Business Law (NBA-SBL).

by Legalnaija | Jan 18, 2023 | Uncategorized

Chinyere is a Partner in Firm of Jackson, Etti & Edu, Lagos–Nigeria and has over 32 year’s practical legal experience in Intellectual Property law, where she is internationally recognised as an expert. She also advises varied government agencies on IP related issues, particularly Law reform. Chinyere is also a medico-legal practitioner and heads the firms Health & Pharmaceutical Practice group, offering tailor made solutions to clients sector specific needs.

She is highly respected by peers and clients alike, with some notable industry appointments & professional recognitions, which include appointment as current Chairperson, Nigerian Bar Association(NBA) Women Forum, Past Council Member & Treasurer-NBA, Section on Business Law (SBL), Inaugural Chairperson, IP Committee NBA-SBL, Patron of the Law Society, Faculty of Law, University of Lagos; Member – Dispute Resolution Panel, Nigerian Copyright Commission. Chinyere was nominated as one of 20 most influential women in Business Law in Nigeria in 2020/21, by Business Day Newspaper, was nominated as one of Managing Intellectual Property’s (MIP’s) Top 250 Women in IP, worldwide 2021/22, and one of the 50 most influential women in the Legal Profession in Nigeria (Business Day Newspaper, April 2011). She is Ranked in Chambers Global, as a Leading Individual in IP in Nigeria, as well as is recognised as an expert in Who Is Who Legal Nigeria, to mention a few.

Chinyere has acquired first hand experience about the challenges associated with building a successful career, as a female professional, attaining a work life balance and embracing the necessary diverse role changes along the way. With a passion for assisting young people reach their full potential in the work place, she founded the Heels & Ladders Career Mentorship Club, where she provides inspiring & motivational guidance and tips for career success for female professionals seeking career growth.

She is on the Advisory Board of a number of NGOs and speaks regularly at workshops, seminars and conferences (locally and internationally) on varied topics of interest.

Registration Details;

Physical Session:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 10th January, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg Link: https://bit.ly/3haXvfy

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Fee: 50,000

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 10th January, 2023)

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3fIJvcq

Iyanujesu is a first-class graduate (among the top 30 (0.6%) out of 5,689 students) from the Nigerian Law School. She is an associate in a leading commercial law firm in Lagos, Nigeria, where she advises energy companies on different aspects to project structuring, development, and financing. She advises clients in different sectors on corporate, commercial, oil and gas, mergers and acquisitions, financing, power, infrastructure, and capital markets. She is skilled in legal advisory, regulatory compliance, contract negotiation, research, and writing. She advocates leadership, volunteering, and teamwork. She has to her name several leadership and entrepreneurial awards. She enjoys writing, and she has an academic blog where she writes on commercial issues-

Iyanujesu is a first-class graduate (among the top 30 (0.6%) out of 5,689 students) from the Nigerian Law School. She is an associate in a leading commercial law firm in Lagos, Nigeria, where she advises energy companies on different aspects to project structuring, development, and financing. She advises clients in different sectors on corporate, commercial, oil and gas, mergers and acquisitions, financing, power, infrastructure, and capital markets. She is skilled in legal advisory, regulatory compliance, contract negotiation, research, and writing. She advocates leadership, volunteering, and teamwork. She has to her name several leadership and entrepreneurial awards. She enjoys writing, and she has an academic blog where she writes on commercial issues-