by Legalnaija | May 24, 2023 | Uncategorized

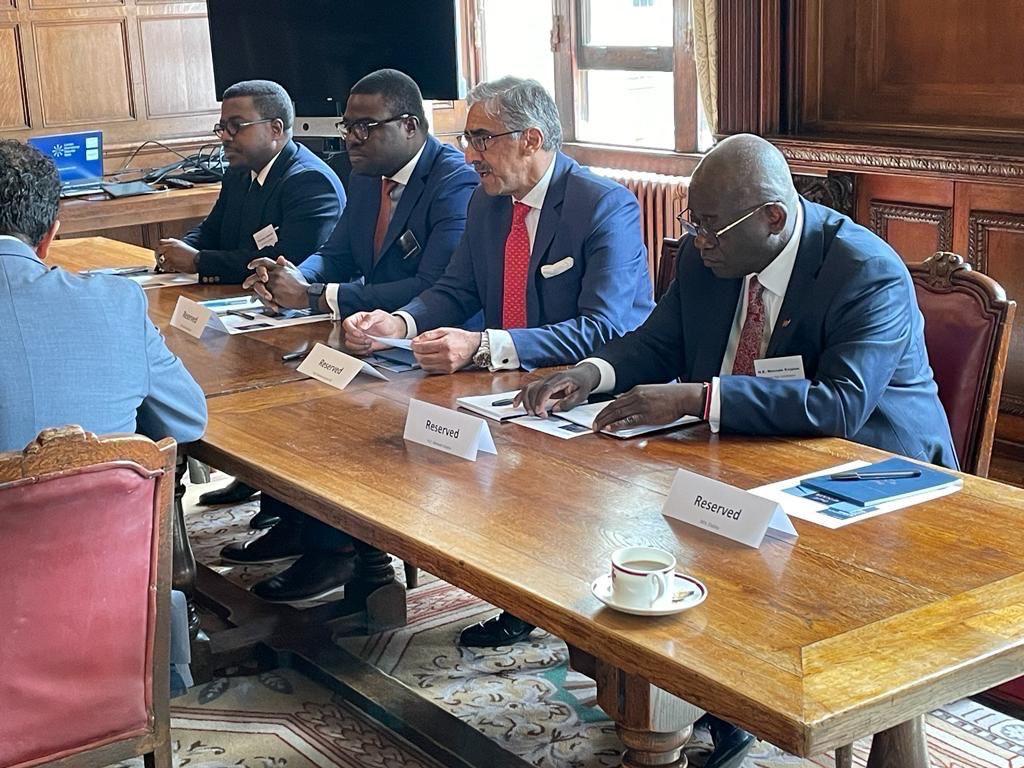

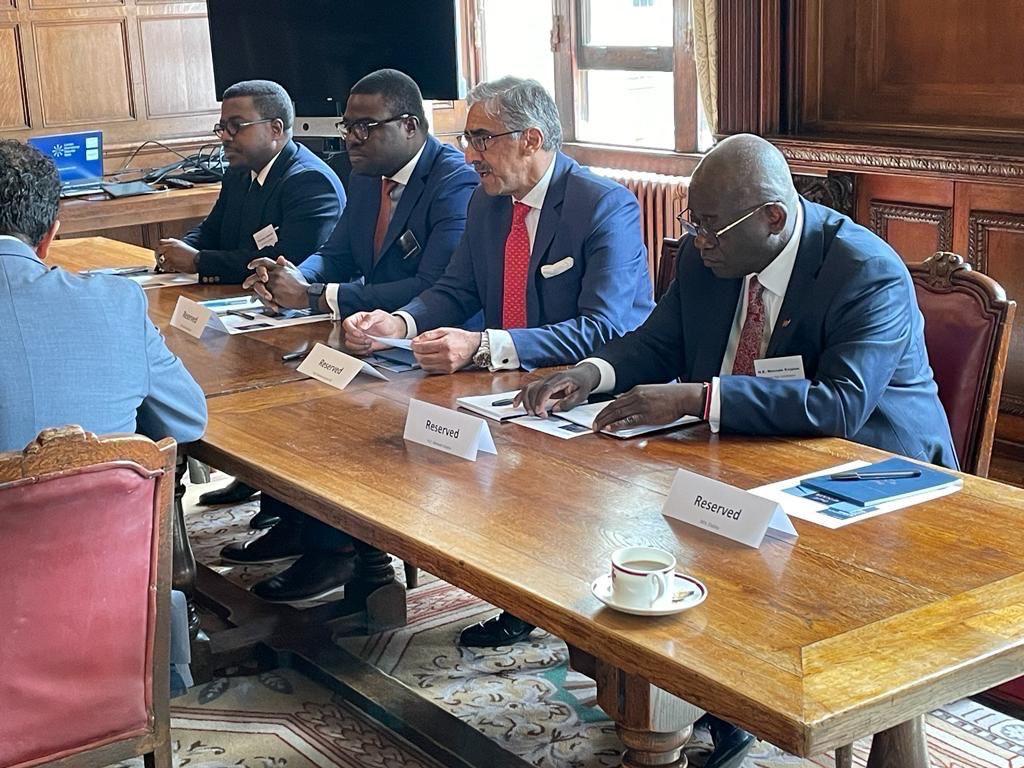

The Chairman of the International Law Association, Arbitration Committee, Mr. Tolu Aderemi, has charged international arbitrators to develop sector-focused expertise. Aderemi made this charge in London on Wednesday, May 17, 2023 during the public presentation of the book, The Palgrave Handbook of Arbitration in the African Energy and Mining Sectors, co- edited by the Professor Damilola Olawuyi, SAN and Dr Victoria Nalule, at the Parliament Chamber, Middle Temple Hall, United Kingdom.

Aderemi, who also authored a chapter in the Handbook on the Recognition and Enforcement of Energy Arbitration Awards, decried the spate of challenges to energy arbitral Awards. According to him, the somewhat lack of understanding or the appreciation of the technicalities of energy disputes are often reflected in the quality of submissions made by Counsel in their pleadings and the arbitral Award rendered by the Tribunal.

Aderemi, who is also a Partner with the firm of Perchstone & Graeys LP, stressed that basic knowledge of practice and procedure of Arbitration has become obviously insufficient to sit over energy-related disputes. He therefore encouraged energy arbitration practitioners to seek technical support either from local sector players or foreign counterparts; particularly at a time when the world is transitioning to a low carbon era in line with the net-zero carbon emission commitment by year 2050.

On his part, the co- editor of the Handbook, Professor Damilola Olawuyi, SAN, noted that the publication of the Handbook has become imperative in view of increasing use of ADR as an alternative mechanism for dispute resolution across the Continent. He emphasized that it is a Handbook which will be periodically reviewed to standardize its content.

On his part, the Chairman of the occasion, Kenyan High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Ambassador Manoah Esipisu lauded the initiative and emphasized the need for capacity building, particularly in areas of renewable energy and water law. The Ambassador stated that the aggressive development of the Kenyan energy market and also chronicled the increasing strides of the Kenyan government to develop the Kenyan energy market.

The Managing Partner of the Host firm, McNair International, Prof Qureshi, KC, welcomed the publication of the Handbook as one of their products and hopes that its rich content will become useful for cross- border deals.

International arbitration has become one of the veritable tools for resolving high- valued commercial disputes and has been adjudged to be one of the most efficient mechanisms for dispute resolution in the energy sector. According to it’s Users, arbitration is effective, efficient and fosters Continuous business relationships between parties. In recent times, Lawyers with minimal training in arbitration may have indirectly imported the traditional practice of technicalities which occasion delays in the Court into arbitration.

This has seen arbitration references spanning periods between 6-48months before conclusion. Users have condemned this trend as it makes the use of Arbitration less fashionable and attractive for the very purpose for which it was conceptualized- quick and effective dispute resolution mechanism. Nigeria has been in the forefront of advocating the use of Arbitration for resolving commercial disputes thereby strengthening its laws and Rules.

Presently, the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, Laws of Federation, 2004 is currently being amended and awaiting Nigeria’s outgoing President Muhammad Buhari, to accent it before the lapse of his tenure.

by Legalnaija | May 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

Folashade Alli is a Partner at Folashade Alli & Associates, and brings over 30 years breadth and depth of experience to significant commercial projects and strategic transactions. She has a skill for solving complex legal problems and her expertise makes her an exceptional lawyer with strong business acumen. A Chartered Arbitrator, Folashade Alli is recognized as one of the leading arbitrators in Nigeria with over 35 years’ experience cutting across Commercial legal practice and International Arbitration. Mrs Alli is a member of several local and international Institutions include;

- Member ICC Commission on Arbitration and ADR

- Member of the ICC Task Force on Corruption in International Arbitration

- Chairman of the Nigerian Bar Association Section on Legal Practice Professional Ethics Committee

- Vice-Chairman of the Nigerian Bar Association, Section on Business Law Committee on International

Trade Law

- Executive Committee Member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb) UK (Nigeria Branch)

- Member of the Professional Conduct Committee of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb) UK

- Treasurer of the Nigeria Bar Association, Section on Legal Practice

Boards:

- Governing Council of Afe Babalola University

- Board of Governors, Day Waterman College, Ogun State

- Board of Trustees, United Way Greater Nigeria (UWGN)

- Board of Directors, AIFA Reading Society

Details of the Training:

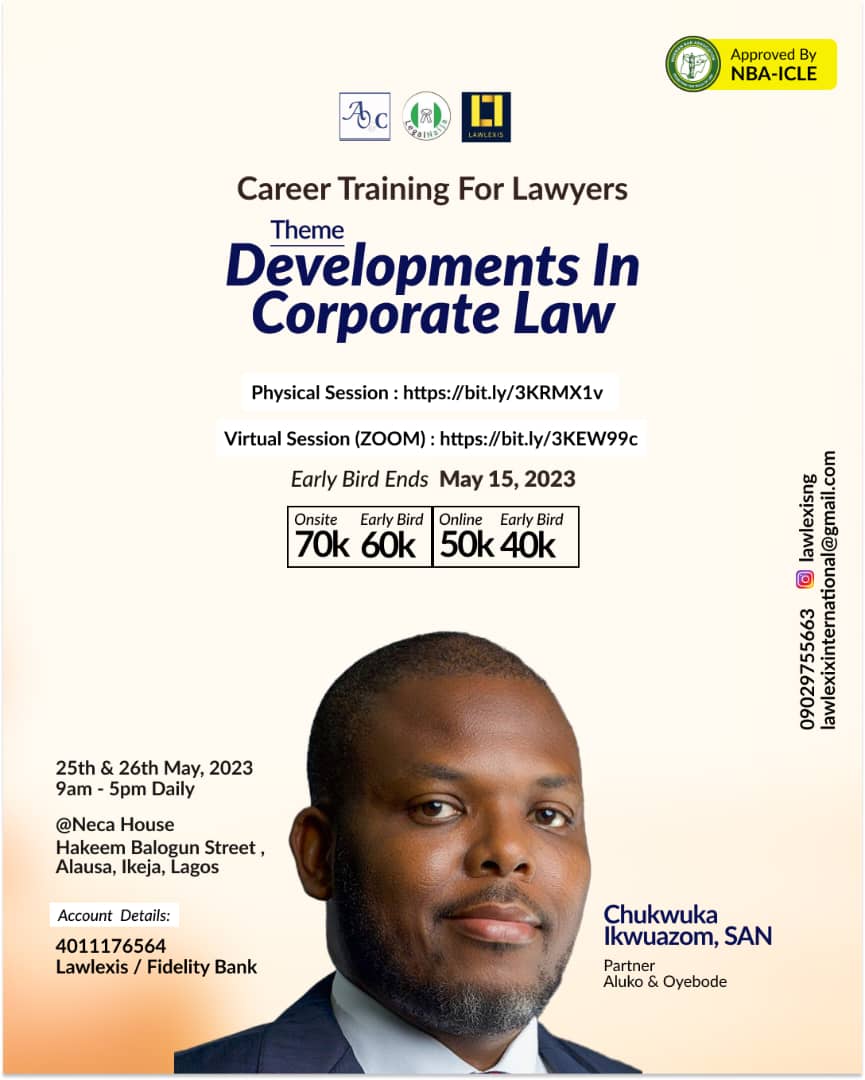

Theme: “New Developments In Corporate Law”.

Date: 25th and 26th May, 2023

Time: 9am – 5pm daily

Modules:

– Tax Law

– Ethics and Corporate Governance

– Energy Law

– ESG And Risk Management

– Capital Markets And Securities Law

– Commercial Arbitration

Members of Faculty

– Mr. Tolu Aderemi (Partner Perchstone & Graeys)

– Mrs. Folashade Alli (Partner, Folashade Alli & Associates)

– Dr. Ayodele Oni (Partner, Bloomfiled Law Practice)

– Mr. Chukwua Ikwuazom SAN (Partner, Aluko & Oyebode)

– Miss Bukola Iji (Partner, SPA Ajibade & Co.)

– Mr. Dayo Adu (Partner, Famsville Solicitors)

Physical registration:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 15th May, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg link: https://linktr.ee/Lawlexis

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 15th May, 2023)

Regular Fee: 50,000

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3KEW99c

Bank Transfer Details;

Name: Lawlexis International

Bank: Fidelity Bank

Acct Num: 4011176564

Registration fee covers lecture materials, and Certification. Participants also get 10 ICLE Points for participation.

by Legalnaija | May 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

Bukola is a Partner at S. P. A. Ajibade & Co and is currently the departmental head for Capital Markets. She has comprehensive knowledge of IPOs, rights issues and other capital raising exercises. She advises on legal issues arising under the Investment and Securities Act, the Rules and Regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Pension Reform Act, the Banks and Other Financial Institutions (Amendment) Act, the Supervisions Circulars & Guidelines of the Central Bank of Nigeria and the Listing Rules of the Nigerian Stock Exchange.

’Bukola also advises on corporate structuring and restructuring, including joint venture agreements, equity incentive plans, shareholder agreements, mergers and acquisitions. She recently led a team that provided services to a private equity fund by conducting compliance and governance due diligence (in line with the World Bank ESG Toolkit) on two investee companies; an online travel company and an agro chemical/crop yield advancement and production company. She has also acted as Company Secretary for an insurance company and in that capacity was in-house counsel with responsibility for the re-capitalization and subsequent merger of the company with another insurance company.

Details of the Training:

Theme: “New Developments In Corporate Law”.

Date: 25th and 26th May, 2023

Time: 9am – 5pm daily

Modules:

– Tax Law

– Ethics and Corporate Governance

– Energy Law

– ESG And Risk Management

– Capital Markets And Securities Law

– Commercial Arbitration

Members of Faculty

– Mr. Tolu Aderemi (Partner Perchstone & Graeys)

– Mrs. Folashade Alli (Partner, Folashade Alli & Associates)

– Dr. Ayodele Oni (Partner, Bloomfiled Law Practice)

– Mr. Chukwua Ikwuazom SAN (Partner, Aluko & Oyebode)

– Miss Bukola Iji (Partner, SPA Ajibade & Co.)

– Mr. Dayo Adu (Partner, Famsville Solicitors)

Physical registration:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 15th May, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg link: https://linktr.ee/Lawlexis

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 15th May, 2023)

Regular Fee: 50,000

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3KEW99c

Bank Transfer Details;

Name: Lawlexis International

Bank: Fidelity Bank

Acct Num: 4011176564

Registration fee covers lecture materials, and Certification. Participants also get 10 ICLE Points for participation.

by Legalnaija | May 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

Dr. Ayodele Oni is a Partner at Bloomfield LP and continues to provide excellent and commercially savvy legal solutions, in connection with electricity, oil & gas projects, financing, acquisitions and restructuring. He has a knack for creating ingenious and effective strategies to ensure the success of transactions he is involved in. Ayodele is also an active leading voice and thought leader in the development of many transformative policy changes in Nigeria, especially in the energy (oil, gas and electric power) sector. Specifically, he has played key roles in developing template documents, rules and regulations, used in the natural gas and electric power sectors.

Ayodele has also been recognized as being “in a league of his own” by the internationally renowned directory, Who’s Who Legal and has also been ranked amongst the World’s leading lawyers in the Chambers and Partners and The Legal 500. Ayodele has been actively involved in several oil and gas transactions, including the Shell divestment deals and Chevron’s divestment of interests in a number of oil mining leases. He has also advised and continues to advise on a number of marginal fields transactions (including the year 2020 marginal fields bid round) and several oil and gas acquisition, divestment and financing transactions.

Ayodele was part of the team that provided legal advisory to the Bureau of Public Enterprises on the post-privatization restructuring of the electric power sector. He has also provided legal, policy and regulatory support to the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission. Furthermore, he has advised the World Bank on electric power sector related issues. Ayodele maintains a seat at the table in the negotiation of almost all major electric power sector transactions in Nigeria and remains key in the negotiation of energy (including refining and pipeline) infrastructure projects and financing transactions, across Nigeria. He has been described as being “responsive and valuable”, is noted for “excellent service” and his “keen work ethic and an unyielding commitment to quality”. He is an adjunct lecturer and author of leading energy texts.

Details of the Training:

Theme: “New Developments In Corporate Law”.

Date: 25th and 26th May, 2023

Time: 9am – 5pm daily

Modules:

– Tax Law

– Ethics and Corporate Governance

– Energy Law

– ESG And Risk Management

– Capital Markets And Securities Law

– Commercial Arbitration

Members of Faculty

– Mr. Tolu Aderemi (Partner Perchstone & Graeys)

– Mrs. Folashade Alli (Partner, Folashade Alli & Associates)

– Dr. Ayodele Oni (Partner, Bloomfiled Law Practice)

– Mr. Chukwua Ikwuazom SAN (Partner, Aluko & Oyebode)

– Miss Bukola Iji (Partner, SPA Ajibade & Co.)

– Mr. Dayo Adu (Partner, Famsville Solicitors)

Physical registration:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 15th May, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg link: https://linktr.ee/Lawlexis

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 15th May, 2023)

Regular Fee: 50,000

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3KEW99c

Bank Transfer Details;

Name: Lawlexis International

Bank: Fidelity Bank

Acct Num: 4011176564

Registration fee covers lecture materials, and Certification. Participants also get 10 ICLE Points for participation.

by Legalnaija | May 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

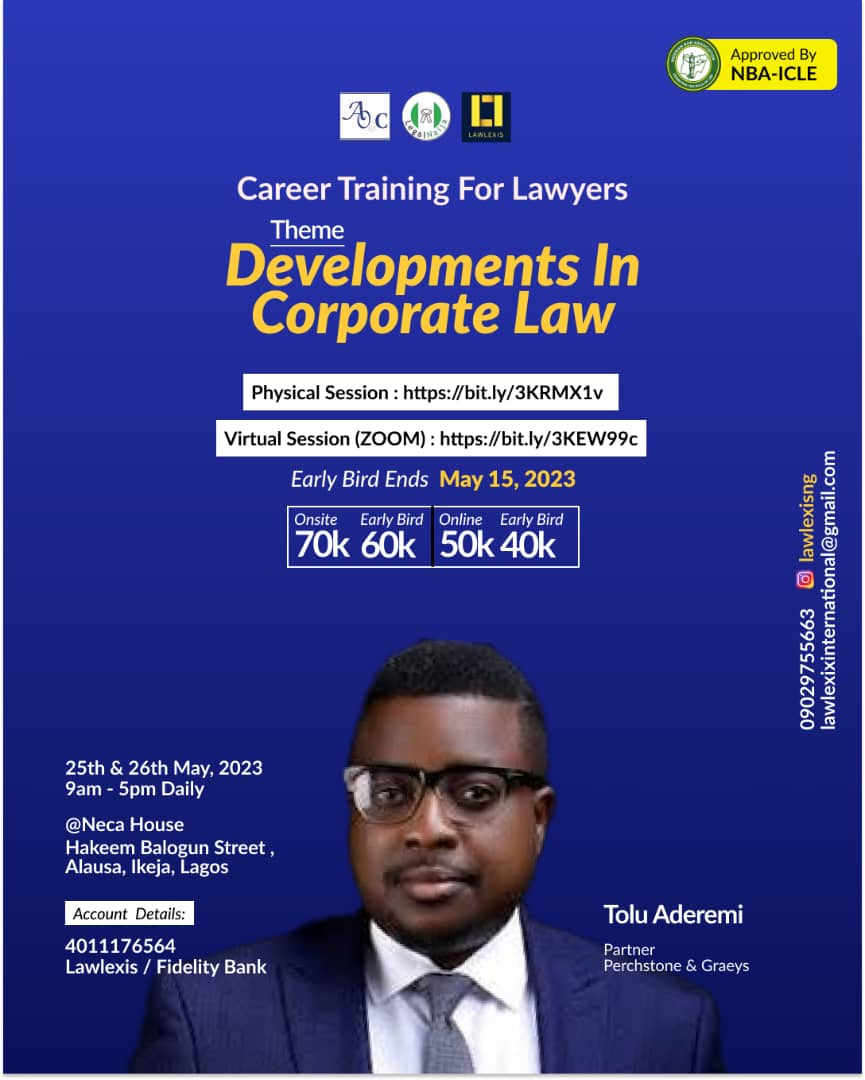

Tolulope Aderemi is a John Taylor scholar of the prestigious University of Aberdeen, Scotland, a Visiting Professor at the Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti, a Doctoral student at the Durban University of Technology, South Africa He is the Chairman, International Law Association (ILA) Arbitration Committee, Chairman, Section on Business Law of the Nigerian Bar Association, Training Committee and Partner/Director, Perchstone & Graeys Consulting Limited (UK), the United Kingdom branch of the company. Tolulope’s expertise has been firmly established in oil & gas, power/electricity, commercial litigation and international arbitration. In 2021, his portfolio expanded into superintending over the Perchstone & Graeys’ Consulting Services (UK) whose focus is to drive multi-jurisdictional investment into Nigeria from diverse areas which include but not limited to oil & gas, fintech, power and real estate.

Tolulope is a member of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), Commission on Arbitration & ADR pursuant to his nomination by Nigeria to Paris. He is a member of the Arbitration and Dispute Resolution Committee of the International Bar Association (IBA) as well as a member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (UK), Nigerian Branch. Tolulope is an accomplished author and editor of several sector-focused book publications some of which include one of Nigeria’s best texts on arbitration; the International Commercial Arbitration: A Practitioner’s Perspective’ and more recently, a book titled ‘From the Ivory Tower To The Hallowed Halls of Justice, a book in honour of retired Hon. Justice Mojeed Owoade of the Nigerian Court of Appeal.

Details of the Training:

Theme: “New Developments In Corporate Law”.

Date: 25th and 26th May, 2023

Time: 9am – 5pm daily

Modules:

– Tax Law

– Ethics and Corporate Governance

– Energy Law

– ESG And Risk Management

– Capital Markets And Securities Law

– Commercial Arbitration

Members of Faculty

– Mr. Tolu Aderemi (Partner Perchstone & Graeys)

– Mrs. Folashade Alli (Partner, Folashade Alli & Associates)

– Dr. Ayodele Oni (Partner, Bloomfiled Law Practice)

– Mr. Chukwua Ikwuazom SAN (Partner, Aluko & Oyebode)

– Miss Bukola Iji (Partner, SPA Ajibade & Co.)

– Mr. Dayo Adu (Partner, Famsville Solicitors)

Physical registration:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 15th May, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg link: https://linktr.ee/Lawlexis

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 15th May, 2023)

Regular Fee: 50,000

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3KEW99c

Bank Transfer Details;

Name: Lawlexis International

Bank: Fidelity Bank

Acct Num: 4011176564

Registration fee covers lecture materials, and Certification. Participants also get 10 ICLE Points for participation.

by Legalnaija | May 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

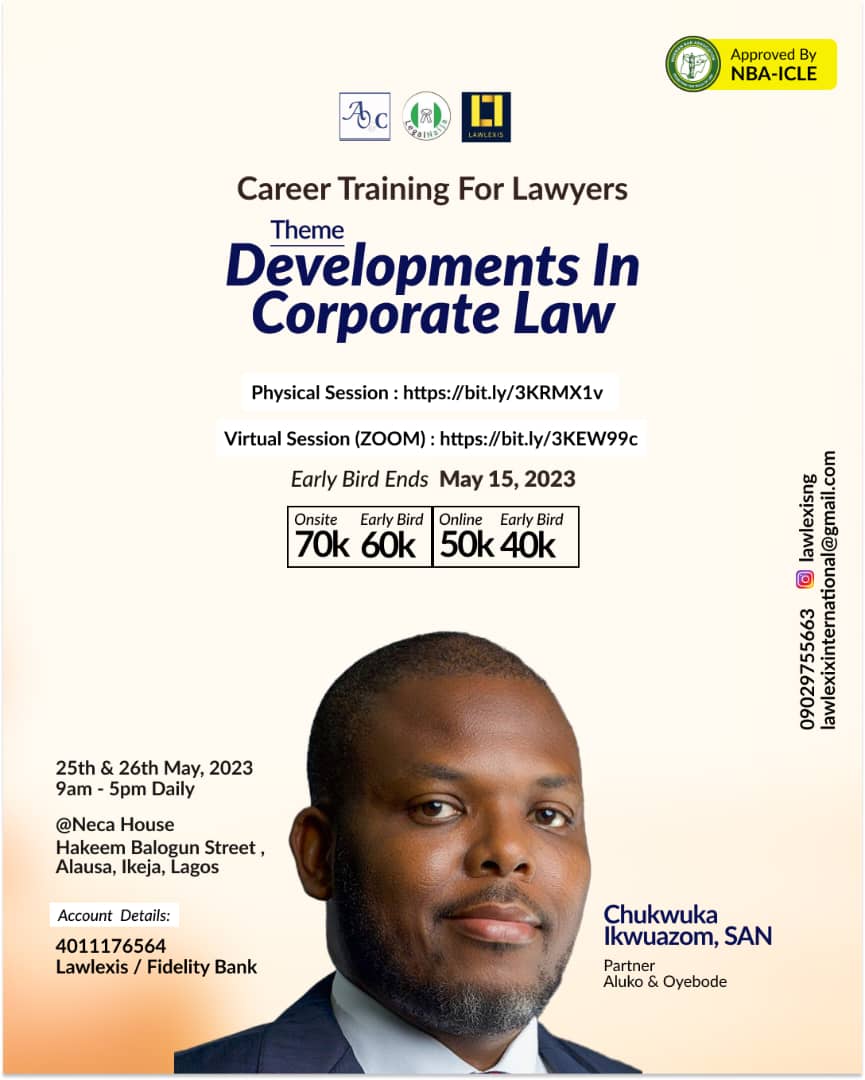

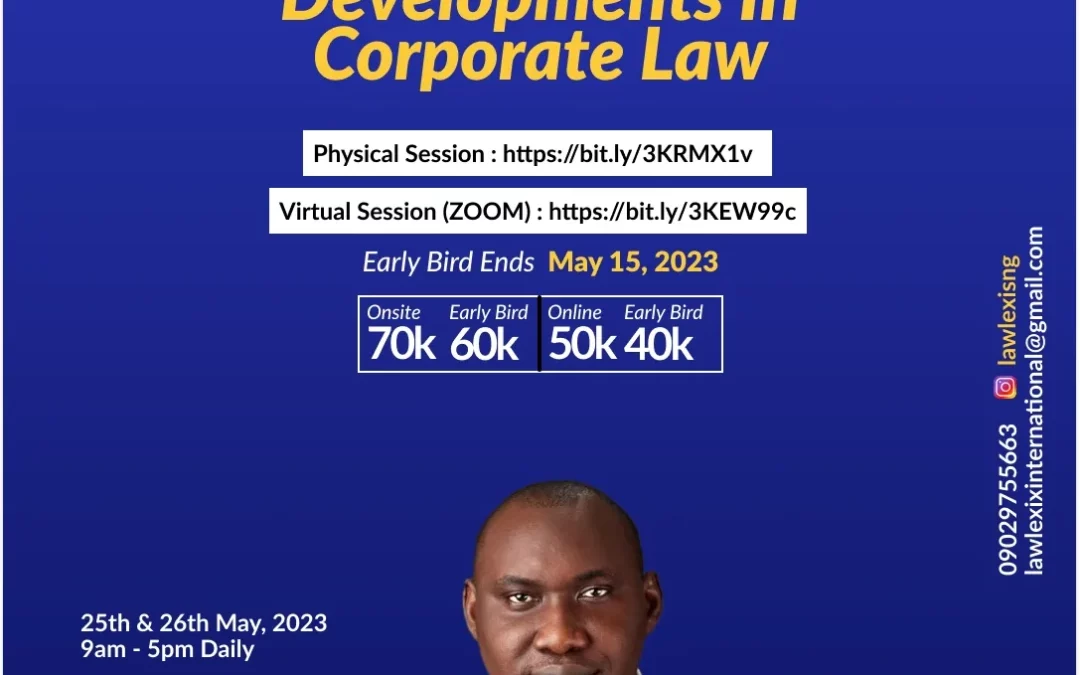

Chukwuka Ikwuazom heads the Taxation practice and is a key member of our Litigation, Dispute Resolution and Risk Management practice at Aluko & Oyebode. Chukwuka has considerable tax advisory and adjudicatory experience. He renders ongoing tax advice to the Firm’s clients, including those in the oil and gas sector. He has also represented clients in tax litigation before several courts in Nigeria. As a Partner in our Litigation, Dispute Resolution and Risk Management practice, Chukwuka has worked closely with Babatunde Fagbohunlu as lead counsel in representing clients in numerous litigation and arbitration proceedings. Chukwuka was a key member of the team (led by Babatunde Fagbohunlu) which won a favourable award for our clients in an arbitration involving several tax disputes arising from the operation and performance of a 1993 PSC executed between the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation and a number of IOCs.

Details of the Training:

Theme: “New Developments In Corporate Law”.

Date: 25th and 26th May, 2023

Time: 9am – 5pm daily

Modules:

– Tax Law

– Ethics and Corporate Governance

– Energy Law

– ESG And Risk Management

– Capital Markets And Securities Law

– Commercial Arbitration

Members of Faculty

– Mr. Tolu Aderemi (Partner Perchstone & Graeys)

– Mrs. Folashade Alli (Partner, Folashade Alli & Associates)

– Dr. Ayodele Oni (Partner, Bloomfiled Law Practice)

– Mr. Chukwua Ikwuazom SAN (Partner, Aluko & Oyebode)

– Miss Bukola Iji (Partner, SPA Ajibade & Co.)

– Mr. Dayo Adu (Partner, Famsville Solicitors)

Physical registration:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 15th May, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg link: https://linktr.ee/Lawlexis

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 15th May, 2023)

Regular Fee: 50,000

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3KEW99c

Bank Transfer Details;

Name: Lawlexis International

Bank: Fidelity Bank

Acct Num: 4011176564

Registration fee covers lecture materials, and Certification. Participants also get 10 ICLE Points for participation.

by Legalnaija | May 17, 2023 | Uncategorized

“The Police is your friend.”

This phrase was intended to be reassuring and to help rebrand the Nigerian police force, but this PR bird did not just take flight. In fact, according to Vera Onana, a phrase that was intended to allay public misgivings and fears about the police only served to make it out to be a hilarious irony. Additionally, using “is” rather than “are” is a glaring grammatical mistake given that the phrase is plural.

This article does not, however, attempt to evaluate the English language proficiency of the Nigerian Police Force or critique a public relations campaign that failed to have the desired effect. Neither will this article take you on a depressing tale of the statistics on police brutality in Nigeria. This article will make better use of your time.

It is important to recognize that public perception is not homogenous and that opinions can vary significantly within and across communities. However, many Nigerians do not hold the Police in very high regard. Scratch: Many Nigerians do not hold law enforcement in very high regard, and for very good reasons too!

However, none of the very good reasons for mistrusting law enforcement is also an excuse to assault a police officer or any law enforcement officer. But if you are a celebrity or very powerful personality and you need other compelling factors to convince you why you must not, against your better judgment, assault a police or law enforcement officer other than notable and obvious reasons such as assaulting a law enforcement officer being a criminal act and it being a direct act of disrespect for their authority and the rule of law they represent, then let me quickly spell out other reasons why you should not assault or condone the assault of a police officer.

- Upholding the Rule of Law: Assaulting a police or law enforcement officer undermines the very foundation of the rule of law. The rule of law ensures that everyone is subject to and protected by the law, including both civilians and law enforcement personnel. When an officer is assaulted, it sends a message that some individuals believe they are above the law or can take justice into their own hands. This erodes trust in the legal system and can lead to a breakdown in social order.

- Protecting Public Safety: Despite their well-documented failings, police and law enforcement officers play a crucial role in ensuring public safety. They respond to emergencies, investigate crimes, and maintain order in society. Assaulting an officer not only puts their safety at risk but also hampers their ability to carry out their duties effectively. By attacking a law enforcement officer, individuals jeopardize the safety of the community they serve, as it may deter officers from taking proactive measures to prevent crime and protect citizens.

- Preserving the Integrity of the Justice System: Assaulting a police or law enforcement officer can have far-reaching implications for the integrity of the justice system. Officers are often called upon to serve as witnesses in criminal cases, and their credibility and reliability are essential to ensuring a fair trial. When an officer is assaulted, it can undermine their ability to provide accurate testimony or cooperate fully with investigations, leading to challenges in prosecuting offenders and potentially resulting in miscarriages of justice.

- Promoting Respect for Human Rights: You cannot fight for human rights for all while neglecting the rights of others. Respect for human rights, including the right to physical integrity and security, is a fundamental principle that societies strive to uphold. Police and law enforcement officers are tasked with protecting these rights and ensuring justice for all. Assaulting an officer violates their basic human rights and, by extension, undermines the principle of respecting the rights of others. Upholding the sanctity of human rights is vital for maintaining a just and equitable society.

- Fostering Trust and Collaboration: Trust between law enforcement and the community is essential for effective crime prevention and solving cases. Assaulting an officer erodes the trust and cooperation necessary for a productive relationship between law enforcement and the public. When trust is lost, individuals may be less willing to come forward with information or seek assistance from law enforcement, hindering efforts to address crime and maintain community safety.

I am not under any presumptions, and I understand that many of us are disgruntled and angry at the “system” and the agencies that serve it, particularly law enforcement agencies and agents. However, we must deconstruct the system and look beyond the veil of these agents, who are trained to carry out instructions to the latter. It’s essential to recognize that police and law enforcement officers are part of a larger system and are often tasked with carrying out instructions or policies set by higher authorities or governing bodies. It’s crucial to separate the actions of individual officers from the broader systemic issues that may exist.

Addressing grievances and seeking change in the system requires understanding the underlying structures, policies, and practices that shape law enforcement agencies. By directing attention towards systemic issues, it becomes possible to advocate for meaningful reforms that can lead to more equitable and just outcomes.

It is important to approach these efforts with a constructive mindset, acknowledging that the vast majority of law enforcement officers strive to fulfill their duties responsibly and ethically. By focusing on systemic factors and engaging in meaningful discussions and actions, it becomes possible to drive positive change while promoting a more just and accountable law enforcement system.

It’s important to note that while assaulting law enforcement officers is considered wrong, this does not mean that law enforcement is immune to criticism or that individual officers are exempt from accountability for any wrongdoing. Upholding the law and maintaining order should always be balanced with respect for human rights and the principles of justice.

So, while the Nigerian Police Force is not your friend, it is neither your enemy, and you should not assault a police or law enforcement officer—not even if you are the son of an Afrobeat legend.

Annakar, Hallelujah Tor Esq. is a lawyer based in Abuja with interests in corporate commercial law, technology and human rights.

by Legalnaija | May 12, 2023 | Training, Uncategorized

Dayo Adu is the Managing Partner at Famsville Solicitors, he advises on due diligence, Regulatory and Compliance audit, corporate and internal investigations, and general commercial law. He also renders legal advice on foreign investment in Nigeria, corporate structures for investment, investment incentives; tax breaks for foreign investors and company establishment procedures. He has advised both indigenous and international firms on general commercial laws cutting across different industries and draws from his dispute resolution background.

He is a professional negotiator and mediator (“PNM”) and also an associate member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (“ACIARB”) England. He has also co-authored the Nigeria chapter for several notable international publications on Business Crimes, Labour & Employment Law, Product Liability, Corporate Immigration and Construction Law. He was a working Nigeria member of the Global Employment Institute of the International Bar Association (“IBA”) for several years.

Dayo was recently recognized by the World Bank for his contribution to “Doing Business 2016: Measuring Regulatory Quality and Efficiency”.

Join Dayo Adu at the career training session on Corporate Law holding on the 25th and 26th of May, 2023. To register follow this link buff.ly/3mQP4t5

Details of the Training:

Theme: “New Developments In Corporate Law”.

Date: 25th and 26th May, 2023

Time: 9am – 5pm daily

Modules:

– Tax Law

– Ethics and Corporate Governance

– Energy Law

– ESG And Risk Management

– Capital Markets And Securities Law

– Commercial Arbitration

Members of Faculty

– Mr. Tolu Aderemi (Partner Perchstone & Graeys)

– Mrs. Folashade Alli (Partner, Folashade Alli & Associates)

– Dr. Ayodele Oni (Partner, Bloomfiled Law Practice)

– Mr. Chukwua Ikwuazom SAN (Partner, Aluko & Oyebode)

– Miss Bukola Iji (Partner, SPA Ajibade & Co.)

– Mr. Dayo Adu (Partner, Famsville Solicitors)

Physical registration:

Fee: 70,000 Naira

Early Bird: 60,000 Naira (ends 15th May, 2023)

Venue: NECA House, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos

Reg link: https://linktr.ee/Lawlexis

Virtual Session (ZOOM)

Early Bird: 40,000 (ends 15th May, 2023)

Regular Fee: 50,000

Registration Link: https://bit.ly/3KEW99c

Bank Transfer Details;

Name: Lawlexis International

Bank: Fidelity Bank

Acct Num: 4011176564

Registration fee covers lecture materials, and Certification. Participants also get 10 ICLE Points for participation.

Hurry and take advantage of the Workers Day Offer. Pay 25,000 Naira only when you use the voucher code: YOUNGLAWYER.

For enquiries, please contact: Lawlexis | lawlexisinternational@gmail.com | 09029755663.

by Legalnaija | Apr 20, 2023 | Uncategorized

Arbitral proceedings are expressions of the will of the parties of which party autonomy is consciously guarded. The existence of an arbitration agreement is essential as it indicates the parties’ consent to settle their dispute by arbitration.

The Arbitration and Conciliation Act (ACA) gives no express definition to the term “Arbitration Agreement” but it describes the form of the agreement which is why parties must take extra precautions when executing an arbitration agreement (either as a standalone agreement or as part of another commercial agreement).

By virtue of Section 1(2) of the ACA, an Arbitration Agreement must be in writing and contained in a document signed by the parties or in an exchange of letters, telex, telegram, or other means of communication which provide a record of arbitration agreement, or in any other documents in which the existence of an arbitration agreement is alleged by one party and not denied by another.

Therefore, the way and manner an arbitration agreement/clause is drafted Is very crucial to the commercial relationship between the parties. It is pertinent to note that Arbitral Tribunals have been advised to refuse to conduct arbitration proceedings where the Arbitral clause is ambiguous.

When drafting Arbitration clauses, both the drafters and the parties are advised to state their intent in clear terms devoid of ambiguity and obscurity. To draft a valid Arbitration clause/agreement, the parties must first agree on the following fundamental terms:

- Scope of the Arbitration Agreement:

Parties must agree on the types of disputes that can be referred to arbitration under the agreement. A poorly drafted scope may deprive the tribunal of jurisdiction over all or part of the disputes. It is advisable to refer all disputes to Arbitration. Although parties are at liberty to refer only specific contract claims to arbitration, they may also expand the scope to include all disputes related to the contract, including non-contractual claims. In expressing this scope, Parties may use terms like “all disputes arising out of the contract”, “all disputes in connection or related to the contract”, or “all disputes arising under the contract”.

- Parties:

The parties to the Arbitration Agreement should be clearly stated, they should be natural persons or legal entities who are capable of entering into an agreement of this nature and against whom any award will be enforceable.

- Language of the Arbitration:

This is the language in which all submissions and evidence will be presented during the Arbitral proceedings. The parties should ascertain the language of the proceedings. The language of the arbitration also includes the words, clauses and phrases used in the agreement. This is important especially where parties are from countries with different first languages.

- Number and appointment of Arbitrators

Depending on the complexity, technicalities and the nature of the dispute, a Sole Arbitrator or an Arbitral Tribunal should be specified. Appointing a Sole Arbitrator is cost effective but where the dispute is a complex one with high commercial and reputational value, it is advisable to use a tribunal which consists of three arbitrators. When the parties opt for a tribunal, each party would each appoint an arbitrator and the 2 appointed arbitrators will then agree on a third arbitrator who should also be the chairman, where it is difficult to appoint the arbitrators, parties can agree that appointments be made by an appointing authority or body like the Nigerian Institute of Chartered Arbitrators (NICArb), LCIA etc.

- Features or qualifications of the Arbitrator(s)

One of the advantages of Arbitration over litigation is that it allows parties to determine the qualifications, characteristics, and experience that arbitrators should have before they can be qualified for appointment. This include conditions like nationality, industry/sector experience, biases or previous relationships with any of the parties etc. This is not a compulsory requirement and parties should ensure that the category of arbitrators to be appointed is not unduly narrow and unrealistic.

- Seat of the Arbitration

This refers to the procedural laws of the arbitration. it determines the rights to enforce the arbitral awards and the interim remedies available to the parties. The seat of arbitration has to do with the procedural laws while the venue of arbitration is simply the physical place where the arbitration will take place.

- Governing law of the Arbitration Agreement

This is important especially for international transactions, the law of the substantive contract may be different from the law governing the arbitration agreement.

- Choice of rules to govern the Proceedings.

When drafting an arbitration agreement, you may want to adopt the rules of an established arbitral institution, such as NICArb rules or LCIA, to govern the arbitration procedure. This enables the institution to administer the dispute (for a fee) based on its already established rules which is usually fair and impartial.

- Consolidation and joinder of Arbitral proceedings

This is common in multi-contract arrangements, where different tribunals may be appointed to deal with multiple arbitrations in relation to the same or similar set of facts. Parties should ensure that the arbitration agreements in each interrelated contract allows for consolidation of the various arbitration arising from the same or interrelated contract as non-joinder of this different arbitrations may lead to additional costs, delays, and multiple conflicting decisions.

- Multi-tiered clauses

This avails the parties the opportunity to explore various stages and types of ADR mechanism before finally exploring arbitration. Parties can attempt settlement of the disputes through other ADR mechanisms like Negotiation, Mediation or Conciliation before finally resorting to arbitration. This should be drafted with clear timelines which can be enforced with or without the active participation of any uninterested party in order not to frustrate the entire process.

Conclusion: Having discussed the various components and essential elements in a valid commercial agreement, I will share general guidelines for drafting all these components and a sample arbitration agreement will be provided in the next episode.

Oluwatoyin Bamidele Oni is a Corporate-Commercial Lawyer and a writer whose works are widely published. He has years of experience both in Arbitration, Project Finance, Infrastructure and PPP, Mergers, and Acquisition.

Oluwatoyin Bamidele Oni is a member of the Nigerian Institute of Chartered Arbitrators (NICArb), a member of the Institute of Chartered Secretaries and Administration (ICSAN), a member of Digital Rights Lawyers Initiative (DRLI), a member of The International Organisation of Management Professionals (IOMP), a member of the Intellectual Property Lawyers Association of Nigeria (IPLAN), a member of the Space Law & Arbitration Association (SLAA), and a member of Young International Council for Commercial Arbitration.

by Legalnaija | Apr 18, 2023 | Uncategorized

Introduction

With the global spread of smartphones and the accessibility to internet connections, it comes as no surprise that pharmacists are beginning to gravitate towards the use of online platform to render pharmaceutical care. The intervention of theHonourable Minister for Health in swiftly providing regulation for online pharmaceutical practice did not also come as a surprise.

What are online Pharmacies?

Online pharmacies refer to the delivery of pharmaceutical care through the instrumentality of electronic or digital platforms such as computers and smartphones to patients in circumstances where they cannot have direct access to a pharmacist or in circumstances where, although, they can access physical pharmacies but opt for the online pharmaceutical option for the convenience and privacy that comes with it.

The regulation is divided into 4 parts to wit: Registration and licensing, Inspection Monitoring and Enforcement, Operation of online Pharmacy and General provisions.

Part I- Registration and licensing

Regulation 1 empowers the Pharmacists Council of Nigeria to register internet based pharmaceutical services, same way it does traditional pharmaceutical entities.

Regulation 2,3 and 4 speaks to licencing requirements.

Regulation 3(2)prescribes that physical address of the online pharmacy must be visible online. This provision presupposes that the regulation contemplates a hybrid form of pharmaceutical practice, by which in addition to online presence, the pharmacy must have physical presence.

Regulation 9 provides that internet based pharmaceutical service must comply with the relevant laws relating to Information and Communication Technology such as the National Information Technology Development Agency Act, the Cyber Crime (Prohibition and Prevention) Act etc.

Part II-Inspection and Monitoring

Regulation 10 provides that prior to issuance of licence, the Council shall carry out inspection of the internet based pharmacyat the physical address that hosts the pharmacy.

Part III-Operation of Online Pharmacy

Regulation 12 provides that every internet based pharmaceutical service provider shall make its site user friendly and interactive for the purpose of:

- Consultancy services to patients and clients;

- Educating patients regarding the medications and disease states;

- Contacting patients regarding delays in delivering prescriptions as well as feedback and recalls; and

- Reporting adverse drug reactions and medication errors.

Regulation 14(2) prohibits the sale of dangerous drugs online.

Regulation 17 provides that internet based pharmaceutical service providers must provide a system for safe and secure delivery of medications and ensure that the right medication is mailed to the patient.

Part IV-General Provisions

Regulation 19(2) provides that the premises and sites of internet based pharmaceutical service providerswill be closed by the council where they fail to obtain the requisite licence.

Regulation 21(5) provides that a pharmacist may only register one (1)internet-based platform at any given time.

Offences and Penalties

Regulation 22(3) prescribes imprisonment for a period not less than 6 months or to fine not less than N250,000.00 or to both as penalty for contravention of the Regulation.

Conclusion

There is no gainsaying that the recognition of online pharmacy is laudable as it enhances access to pharmaceutical care. However, one of the drawbacks is the potential decrease in interaction between pharmacists and patients.

Another shortfall of this regulation is its failure to define the practicality of the operation of online pharmacies. Specifically, it fails to specify if online pharmacies registered under the regulation are designed to operate in the same configuration as telemedicine, whereby the Doctor and patient interact through video conferencing.

AUTHORS

AROME ABU

abuaromethecounsellp@gmail.com

JOHN AYOBAMI AKINWUMI

john_akinwumi@yahoo.com

For further information, please contact us at thecounsellegalpractice@gmail.com

THE COUNSEL L-P,PLOT 1014, SAMUEL ADEMULEGUN AVENUE, CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT ABUJA, FCT.

http://thecounsellp.com

Twitter:

@TheCounselLP

+234 803 262 2359

+234 708 115 6539

CAVEAT: THE INFORMATION PROVIDED IN THIS ARTICLE SHOULD NOT BE TAKEN AS PROVIDING LEGAL ADVICE ON THE SUBJECT MATTER. KINDLY SEND AN EMAIL TO thecounsellegalpractice@gmail.com.IF YOU NEED FURTHER LEGAL ADVICE ON THE ISSUES DEALT WITH HEREIN

COPYRIGHT © 2023 THE COUNSEL L-P ALL RIGHTS RESERVED