Introduction

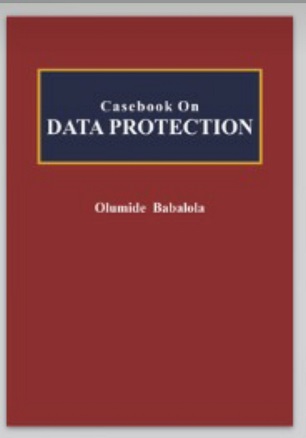

A defining feature of the continuing transformation of our world is the rapid pace of technological change, which has also engendered a heavy reliance on data (both structured and unstructured) on a day-to-day basis. Whether we are talking of personal data, transactional data, web data or sensor data, there is no denying the fact that data now lies at the heart of government, business and indeed our society. It is against the backdrop of the consequences of data collection and its implications for societal development that we must appreciate Casebook on Data Protection.

Data mining and data aggregation have become indispensable tools being used to target individuals by both advertisers and organised crimes. Aggregation is with reference to the compilation of individual items of data, databases or datasets to form large datasets. Data mining, on the other hand, involves the processing of a large dataset using tools to search for particular words or phrases, then refining the search with combined search terms to find individual records of interest. Beyond the nuisance of intrusive and aggressive marketing by organizations and companies, of much more serious concern is the use to which organised crime oppressive regimes, terrorist organizations, private investigators and investigative journalists can put data sources to target people and groups for nefarious purposes.

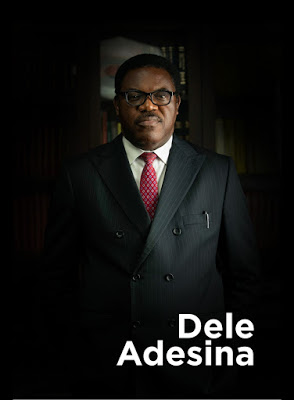

From credit cards to medical and marital information, sensitive personal information and details of children, family members and friends, all can be subject of internet identity theft, fraud and blackmail as a consequence of data mining. Thus, when the author, Olumide Babalola requested me to review Casebook on Data Protection, I did not hesitate for a moment. Indeed, there could not have been a better time for a book that will address the complex issue of data protection than now when COVID-19 distancing policies are accelerating the digital transition.

The author was bold and assertive on how he came about the idea of the book. In the Preface, he resolutely opines:

As a privacy practitioner, I had been frustrated a number of times by the lack of apt authorities to back up my submissions on issues bordering on data protection, being an emerging field, the world over. However, when during the COVID-19 lockdown from the last week of March, 2020, I found myself pooling together foreign decisions on the subject, the idea of this book became conceived on the 57th case.

Reading through the Preface, one detects the author’s concerns for the governance regime of data protection. The reason for complexity and challenge of regulation is not far-fetched. Data is global: mobile networks, multiple apps, and interactive databases that feed on data are located in a cloud where national boundaries have little meaning. Yet, data regulation on the other hand is essentially national, controlled by State and Federal governments whose traditional authority starts and stops at the borders of national jurisdiction. Consequently, even with the way digital technology is globally driving the data revolution, the governance regime and legislative approach to the unfolding developments are still guided by the dynamics of politics, cultural differences and global economic inequality. These in themselves are not necessarily problematic. However, what they present is a patchwork of approaches.

Insights into Casebook on Data Protection

To seek to offer comments on every segment of a 659-page book would certainly be tedious. Thus, what I will be offering is a brief overview, the goal of which is to whet the appetite of each and every one of us to appreciate what this addition to legal jurisprudence offers, and how we can fully amortise its benefits.

The book is divided into fourteen chapters. After an introduction that traces the brief history of data protection in Nigeria, separate chapters are devoted to Definitions, Relationship with other rights; Principles of Data Protection; Exceptions and Derogation; Employment Data; Sensitive Data; Transfer of Data to a Foreign Country; Liability of Data Controllers; Data Subject’s Rights; Data Breach; Remedies; Data Property Rights; Supervisory Authority and Appendices that feature the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation and the NDPR Implementation Framework.

The approach adopted by the author is to introduce what the chapter is about, followed by the facts of the case, the decision of the court, and in some situations, some explanation on the case by way of commentary. It’s a form of digest organised by way of summary of facts and headnotes. In clear anticipation of criticisms that may trail the commentaries as not being argued discursively and academically, or that the author omitted to state his views on points of law where there is no authority or the cases reported are difficult to reconcile, or even a general view that the book did not offer a comprehensive view of the law relating to data as a traditional text would do, the author in his Preface acknowledges:

In order to manage the expectations of readers, it must be noted that, this book neither pretends to be a comprehensive text on the subject nor on academic or otherwise review of the decisions featured therein, rather, it remains casebook of verbatim pronouncements of the courts on data protection. Hence, it is more intended as a practice-reference book and users are advised to read the full decisions for a comprehensive understanding of the court’s reasoning and arguments of parties. It is also advisable to consult other more comprehensive text books on data protection for in-depth understanding of the subject, especially on areas not captured by the decisions featured.

The author again emphasized the above in the first two paragraphs of chapter one, thus, putting no one in doubt that his goal is to aid the busy practitioner by providing him with relevant and readily accessible resource material from which he can locate discussion of a legal issue in this area of law which is gradually emerging in Nigeria. This being the object of the author and the clearly identified limits of the book, one can say he has generally achieved the set goal.

Perhaps, it is also with the busy practitioners in mind that the author felt each chapter should be as complete and self-contained as possible. In this respect, the core of chapter one is the way it gave the real picture and current position of efforts at enacting legislation on data protection in Nigeria. The issuance of the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation (NDPR) by the National Information Technology Development Agency on 25 January 2019 represents the current state of legislation in this field. Chapter two which deals with Definitions features four cases where the courts had opportunity to define a number of data protection terminologies that are commonly in use. Beyond definitions, you also find obiter dicta of the court on varied issues relating to the need to maintain a balance between data protection and freedom of expression, and the need for proportionate sanctions against unlawful processing of data among others.

In chapter three, the author features cases that espoused the interplay of data protection with other sensitive rights such as freedom of expression, intellectual property rights, freedom of information, right to effective remedy, and right to freedom of religion. Chapter four presents an overview of the seven key personal data processing principles under the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The author not only shows that these same principles are what the NDPR has reduced to four, he equally presents relevant judicial decisions touching on these principles.

The exceptions and derogations to data protection are the focus of chapter five. The author clarifies that while the GDPR, in its application, exempts activities such as crime prevention, national security, purely personal or household activities and activities carried out for journalistic, academic or literary expression, the NDPR only expressly provides for exception with respect to transfer of data to a foreign country. The author brilliantly noted how some of the exceptions not provided for under NDPR have been governed by section 45 of the Constitution. The chapter features about twenty-one cases that dealt with the different exceptions under the GDPR. Chapter six gives attention to broad distinction between the treatment of employees’ personal data under the GDPR and the treatment under the NDPR. This is followed by about thirteen judicial decisions that considered the positions under the GDPR. Chapter seven relates to sensitive personal data and judicial decisions interpreting how it can lawfully be processed.

In Chapter eight, the reader is taken through provisions of the NDPR on transfer of data to a foreign country (third countries or to international organizations). It considers the approach under EU law, and how the courts have construed the phrase “adequate level of protection” which the foreign country must ensure for a transfer to take place. In Chapter nine, the author discusses the liability of controllers i.e. the obligations and liabilities that come with a data controller’s influence on personal data, and presents the decisions on data subject’s rights and their enforcement in Chapter ten.

Chapter eleven is on the very important issue of data breach and applicable sanctions. Data breach has been defined as the unlawful and unauthorised acquisition of personal information that compromises the security, confidentiality or integrity of personal information. It features the interesting case of WM Morrison Supermarkets Plc v. Various Claimants. It is a year 2020 decision of the UK Supreme Court. Chapter twelve is on remedies. Among the interesting cases featured is that of Richard Lloyd v. Google LLC in which Lloyds filed a class action on behalf of more than 4 million Apple iPhone users. He alleged that Google secretly tracked some of their internet activities, for commercial purposes in 2012.

In Chapter thirteen, the reader is taken through judicial decisions on the property value (if any) of personal data. The final chapter features decision on supervisory authorities in relation to their expected independence and cooperation.

Conclusion

Casebook on Data Protection without doubt is a remarkably useful collection of cases that fills a gap in legal literature in a rapidly developing subject of far-reaching importance. For this, the author, Olumide Babalola deserves our commendation. The cases are drawn from a great number of sources from all quarters of the globe, hence the author’s note in the Preface that while the cases are not binding on Nigerian courts “…they however offer very useful guidance especially where the wordings of our relevant legislations are similar to their foreign counterpart interpreted”.

As may sometimes be inevitable in a production of this volume, a number of typographical errors such as “Pata Protection” instead of “Data Protection”, “Data Dontrollers” instead of “Data Controllers”, “Data Dreach” instead of “Data Breach”, (see the Table of Contents) are noticed, and to which the author must avert his mind in the next edition. These errors however do not detract from the fact that this is a valuable book. Overall, the book sets us on the right path towards a better understanding of Data Protection in Nigeria. It deserves the widest readership.