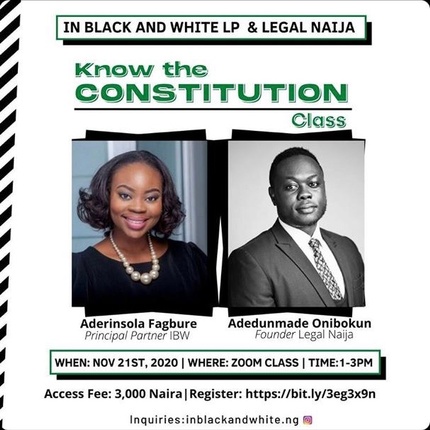

by Legalnaija | Nov 7, 2020 | Uncategorized

Learn the provisions of the Constitution as a Nigerian citizen or visitor. Our speakers, Derin Fagbure and Adedunmade Onibokun are seasoned legal professionals who will be sharing an in-depth analysis of relevant provisions of the Constitution that all citizens should be aware of.

Topics include:

– Brief Intro & History of Constitution

– powers of the Federal Government

– Fundamental objectives

– Citizenship

– Fundamental Rights

– Legislative Powers

– Judicial Powers

– Duties of Local Govt Councils

– Code of Conduct for Public Officials

Register Now Via This Link https://flutterwave.com/store/lawlexis/0gzomd2fhxvi?_ga=2.204572816.1627617939.1604763039-946979208.1599414617

by Legalnaija | Nov 4, 2020 | Uncategorized

On the 20th day of

October 2020, what started as a peaceful protest for over two weeks turned

bloody after the Nigerian Army allegedly unleashed it’s bullets at unarmed protesters

leading to loss of lives and many injured. The protest tagged #ENDSARS was

carried out across many cities in Nigeria and other countries.

Fortunately, a number of

protesters recorded the situation where the world could hear and see the

atrocities allegedly committed by the Nigerian Army. Some broadcasting stations

covered the situation and showed footages of this tragic event taken at the

protest ground.

The Nigerian Broadcasting

Commission (NBC) on Monday the 26th of October 2020, six days after

the tragic shooting at Lekki Toll gate, fined three broadcasting stations,

Arise TV, African Independent Television (AIT) and Channels TV with 3 Million

Naira each. The reason given was that these stations covered the shootings by

posting unverified footages. However the fine received some strong oppositions

one of which is the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP)

who issued NBC 48 hours ultimatum to withdraw the fine or risk legal actions.

SERAP argued that the fine was an attempt to silence the media and restrict

freedom of speech and the press. Also, some Nigerian Lawyers under the aegis of

Digital Rights Lawyers Initiative (DRLI) filed a lawsuit against NBC over the

fines.

While it is true that a number

of fake and old videos were circulating the internet after the shooting occurred,

some videos raises no iota of doubt, one of which is the live video shared by

DJ Switch on Insta Live. From the video, we could see and hear gunshots, people

running, bullets, soldiers shooting at protesters. Despite videos corroborating

the location and presence of some Nigerian soldiers at the scene of the

shooting, the Defence Headquarters claimed the videos shared are fake. As a

result, people have questioned the authenticity of these videos, others have argued

that live videos from social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram cannot

be Photoshopped while it is being recorded.

These questions raises quite a

number of issues for determination in this scenario.

CAN LIVE VIDEOS BE

PHOTOSHOPPED?

Several live coverage on the shootings

were circulated all over social media from the phones of protesters who were

present at Lekki toll gate. Most notably the Lekki shootings where members of

the Nigerian Army were allegedly shooting at protesters. From some of the videos,

we could see that the lights illuminating the Lekki toll gate went off almost

immediately the shootings started.

From the video, we could see

that it was a live coverage on Instagram. However there are contradictory

stories coming from both the witnesses who were at the shooting scene, the

Lagos State government and the Nigerian Army, the question lingering is whether

that video is authentic or photoshopped. Where the Army initially denied being

at the scene.

Without the need for long rigmarole,

the simple answer is that a live video from social media cannot be photoshopped

or edited while it is recording because it is LIVE!!!! While

it is possible for unverified and old videos to circulate during an unrest, it

is impossible for a live video on any social media platforms to be photoshopped.

CAN LIVE VIDEOS BE

ADMISSIBLE IN EVIDENCE?

The admissibility of

electronically generated evidence is governed by Section 84 of the Evidence

Act. The section states as follows:

(1) In any

proceeding, a statement contained in a document produced by a computer shall be

admissible as evidence of any facts stated in it of which direct oral evidence

would be admissible, if it is shown that the conditions in subsection (2) of

this section are satisfied in relation to the statement and computer in

question.

(2) The

conditions referred to in subsection (1) of this section are-

a.

That the document containing the statement was

produced by the computer during a period over which the computer was used

regularly to store or process information for the purposes of any activities

regularly carried on over that period, whether for profit or not, by anybody,

whether corporate or not, or by an individual;

b.

That over that period there was regularly

supplied to the computer in the ordinary course of those activities information

of the kind contained in the statement or of the kind from which the

information so contained is derived

c.

That throughout the material part of that

period the computer was operating properly or, if not, that in any respect in

which it was not operating properly or was out of operation during that part of

that period was not such as to affect the production of the document or the

accuracy of its contents; and

d.

That the information contained in the statement

reproduces or is derived from information supplied to the computer in the

ordinary course of those activities.

Telephones are a form of

computer and social media cannot operate without the use of computers. We have

seen court proceedings, crimes committed, confessions of crime committed,

sealing of contracts, defamatory statement, receipts of payment made and even

corroboration of a crime happening live on social media platforms. Therefore evidence generated from social

media are admissible as they fall under Section 84 of the Evidence Act. As long

as the device containing those content fulfills the requirements of Subsection

2 of Section 84.

IS SANCTIONING A MEDIA

OUTLET WHO POST LIVE VIDEOS OF AN EVENT IN BREACH OF FREEDOM OF THE PRESS

Among the fundamental rights a

person is entitled to is the right to Freedom of Expression and the Press.

Section 39 of the 1999 Constitution provides for the right of expression and

freedom of the press. Generally, an attempt to silence or restrict the press is

a breach of the constitution.

In addition with the

provisions of the constitution, Section 1.2 of the NBC Code on Coverage of

Crisis, Disorder and Emergency, Sections 1.2.6 and 1.2.7 precisely, broadcasting

stations are admonished to verify their news before posting.

With the threat of legal

action, the question is will SERAP succeed if they bring an action as the NBC

is the body in charge of broadcasting stations in the country. The NBC Code in

Section 1.2.6 states that “Broadcasters

using social media sources or any emerging technologies for coverage of

disasters and emergencies shall ensue the veracity and credibility of the

originating material and content”.

Section 1.2.7 states thus “Broadcasters in using social media

sources or any emerging technologies shall ensure due caution and

professionalism in the coverage of disasters and emergencies”.

Also the NBC cannot rely on

any other law or code to justify this sanction as Section 1 (3) the 1999

Constitution states that “If any other

law is inconsistent with the provision of this Constitution, this Constitution

shall prevail and that other law shall to the extent of the inconsistency be

void”.

What NBC would have done is to

investigate the authenticity of the news before imposing fine. The actions of

NBC does not seem sincere as this administration have been repeatedly accused

of attempting to silence the press. If they cannot prove that this news are

unverified then the fine imposed on these stations are illegal and uncalled

for. The media is an essential part of the potency of democracy therefore an

attempt to silence the media is an attempt to disrupt democracy. The only way

the fine will be tenable is if there is evidence that the videos published by these

stations are fake.

CONCLUSION

The action of NBC reminds

people of the proposed plan to curtail hate speech by censoring social media

which have received serious backlash from citizens. With the distrust citizens

have for the government, actions taken like that of NBC will only create more

doubt and distrust of the government. The Digital Forensic Research Lab noted

that the videos showing the shooting are authentic. The fine itself lost its

credibility when the Nigerian Army admitted that they were sent by the Lagos

State government to contain the unrest.

For a satisfying fact check,

the NBC is expected to investigate the authenticity of whatever videos shared

by these broadcasting stations before imposing any form of fine on them.

Article

by Freda Odigie.

Legal

Practitioner at E.A Otokhina & Co

![Visas And Permits Under The Nigerian Immigration Law[1] | KHALID ABDULKAREEM](https://legalnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/khalid-visa2.png)

by Legalnaija | Nov 2, 2020 | Uncategorized

1.0. Introduction

The sources of the Nigerian

Immigration Law are divided into primary and secondary sources. The primary

sources mainly consist of the Immigration Act, 2015, Immigration Regulations,

2017 and the Nigerian Visa Policy, 2020, while the secondary sources are the

1999 Constitution as altered and Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content

Development Act 2010. Embedded under these laws are visas and permits that must be obtained by

foreigner desirous of entering into the country for one reason or the other.

The Nigerian Immigration Service is the body statutorily mandated and empowered

to issue or grant such visas and permit.

This article serves as a summary exposition of these relevant visas and

permits.

2.0. Classes of visas

available under the Nigerian Law

The categories of visas existing and

obtainable by expatriate under the Nigerian law include the following;

(a)

Transit

Visa/ Entry Permit

This

visa is applicable to foreigners travelling to destinations other than Nigeria

but having reason to stop in Nigeria with visa to their destination. To be

eligible, such foreigner must have a confirmed ticket to his/her final

destination with adequate fund.

(b)

Business

Visa

Business

Visa is meant for foreigners who are interested in establishing business or

investment in Nigeria. It is valid for the period of three months but is

invalid for employment purposes.

(c)

Tourist

Visa

Foreigners wishing to visit

Nigeria for the purpose of tourism or to visit family and friends are required

to obtain tourist visa. Requirement for issuance of tourist visa includes;

evidence of sufficient funds, evidence of hotel accommodation and flight

itinerary. The visa is not valid for employment.

(d)

Diplomatic

Visa

Apart

from being entitled to diplomatic immunity, diplomats and member of their

families are also entitled to diplomatic visas. Eligibility to diplomatic visa

also extends to visiting head of states and their families, top officials of

government and their families, members of accredited international

non-governmental organisations and international organisations.

(e)

VISA

ON ARRIVAL

The

Visa on Arrival channel is available at the port of entry into the Country.

This is available for those whose visa application falls within the qualifying

classes of visas; these include frequent business travellers, emergency relief

workers and holders of passports of African Union countries.

(f)

Subject

to Regularisation Visa (STR)

Foreigners

who seek to work with individuals, corporate bodies or governments in Nigeria

need a STR to do so. Where the position to be occupied by the foreigner is

Chief Executive Officer of the Corporate Organisation, there will be need for

the extract of the minutes of the Board’s resolution.

(g)

Temporary

Work Permit Visa

This

is a short-term employment (TWP visa) is a single entry work visa issued to

foreign nationals to carry out short-term specialised work such as; Audits and

accounts, consultancy services, installation and repairs of specialised

equipment and machineries , maintenance repairs and feasibility studies. A TWP

may be extended for two months with the approval of the Comptroller General of

Immigration.

(h)

Expatriate

Quota

Expatriate

Quota is an approval granted to companies or registered firms to employ the

services of expatriates with relevant competences. One significant use of the

expatriate quota is that it is meant to create an avenue for Nigerian employees

to understudy their expatriate counterparts during the validity of its

issuance.

The two types of expatriate quota

positions are;

(i)

Permanent

Until Review (PUR)

The

PUR expatriate quota is granted on a permanent basis usually to the benefit of

a person occupying a top management position in the company e.g. Chairman or

Managing Director.

The essence of applying for and obtaining the PUR is to exclude these employees

from the hassle that may be experienced in the course of periodic renewal of

residence permits and also to ensure that the local company is able to protect

its investment.

(ii)

Temporary

Expatriate Quota

This

type of expatriate quota is usually reserved for the position of Director and

other employees of the company for between one and three years.

(i)

Combined

Expatriate Residence Permit And Aliens Card (CERPAC)

The CERPAC is a

permission granted to Foreigners to live and work in Nigeria for up to two

years, which is subject to renewal and validity of the expatriate quota. It is

a work and resident permit required for any foreigner to reside in Nigeria for

any lawful purposes excluding Diplomats; Government Officials, Niger Wives;

and Non- Governmental Organizations (NGOs) who are granted CERPAC gratis. The

card is valid for two years, after which application for revalidation must be

made.

The two type of CERPAC are;

(i)

CERPAC Green Card

This card allows foreigner to reside in

Nigeria and carry out an approved activity as stated on the permit or to

accompany a resident or citizen of Nigeria as a dependant.

(ii)

CERPAC Brown Card

This card is mainly a movement chart for

every foreigner in Nigeria or visiting with the intention to remain in the

country beyond 56 days in accordance with registration requirement under the

law. It is also applicable to crew members leaving their ship and staying

ashore in excess of 28 days.

3.0. Concluding Remarks

Conclusively,

this piece has basically dealt with some of the required visas and/or permits

that foreigners seeking to come in to the Country must obtain. Where any

foreigner is found wanting or guilty of non-compliance with the requirements as

set out under the Immigration Law would be subjected to stringent penalties –

ranging from administrative fines to imprisonment and deportation.

Profile

of Khalid Adulkareem:

Khalid

Adulkareem is an associate at Omaplex Law Firm with broad and in depth

understanding in the following areas Immigration Law and Intellectual Property Law,he has advised

and facilitated several transactions

including commercialization of their intellectual

property rights and other areas.

Section 36(1) of the Act and Regulation 12 (1) and (2) of the

Regulation. Also, under Section 33 (1) of the Nigerian Oil & Gas Industry

Content Development Act 2010 operators shall make application to, and receive

the approval of, the Nigerian Nigerian Content Development and Monitoring

Board before making any application for expatriate quota to

the Ministry of Internal Affairs or any other agency or Ministry of the Federal

Government

by Legalnaija | Oct 31, 2020 | Uncategorized

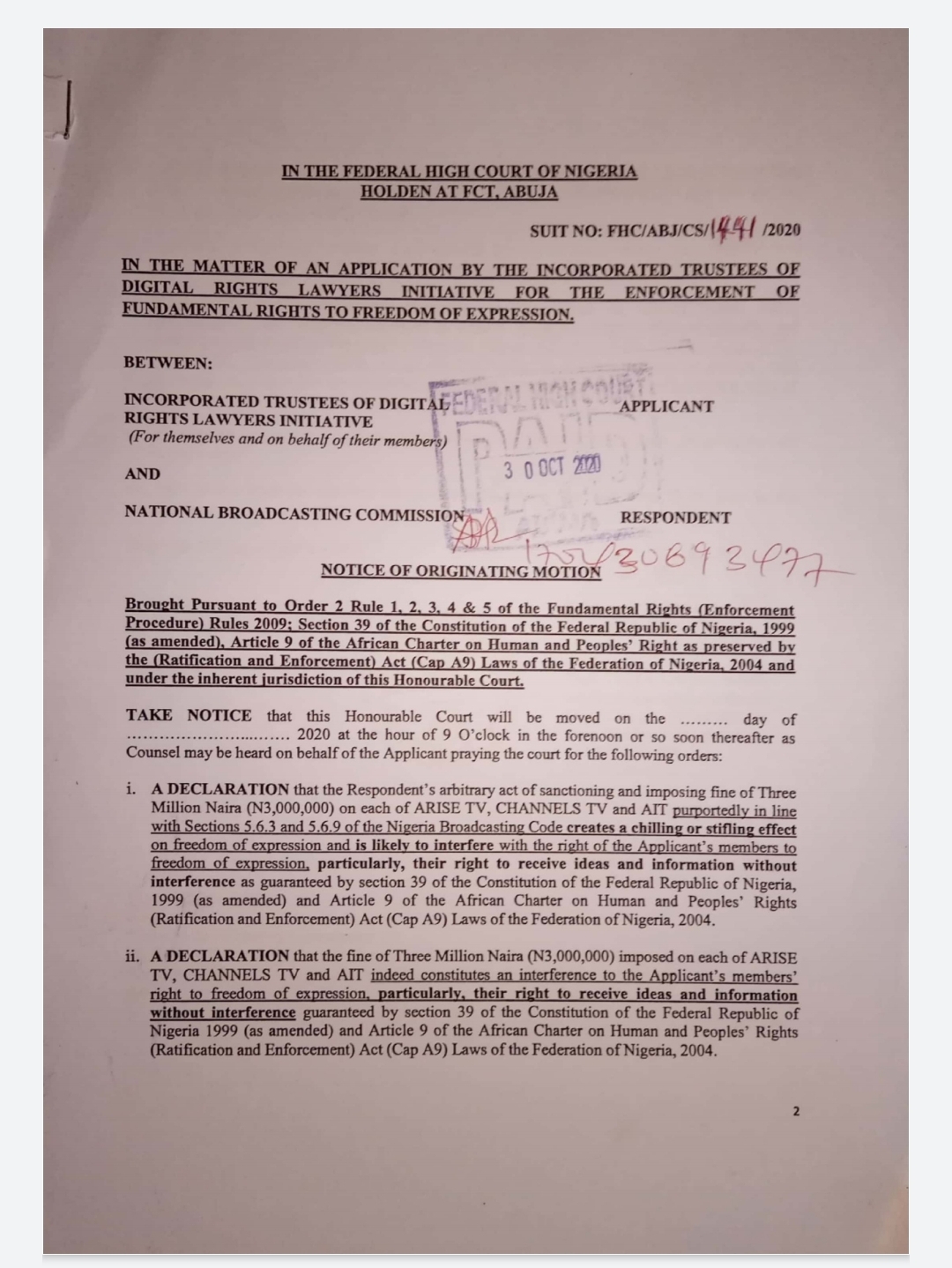

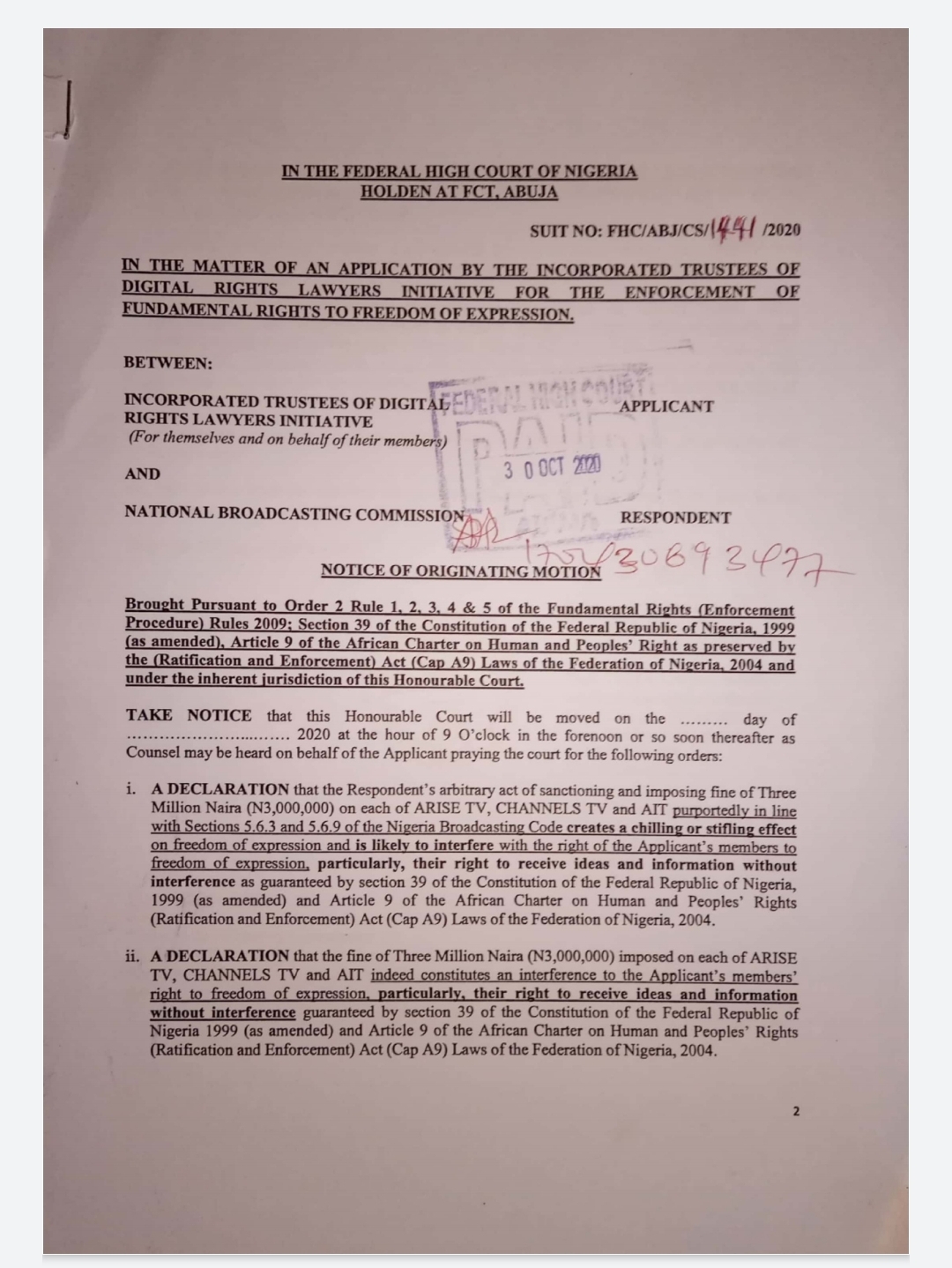

The lawyers’ group known Digital Rights Lawyers Initiative (DRLI) has filed a suit against the National Broadcasting Commission for the fines the agency recently imposed on three television stations namely ARISE TV, Channels TV and AIT. In the suit filed at the Federal High Court, Abuja, on Friday 30th October, 2020 and marked FHC/ABJ/1441/2020 the NGO, whose main objective is to protect and promote digital rights of citizens including freedom of expression, essentially alleges that the sanction and fine imposed on the television stations creates a chilling effect on freedom of expression and constitutes an unjustifiable interference of its members’ right to freedom of expression particularly, their right to receive ideas and information from the sanctioned television stations.

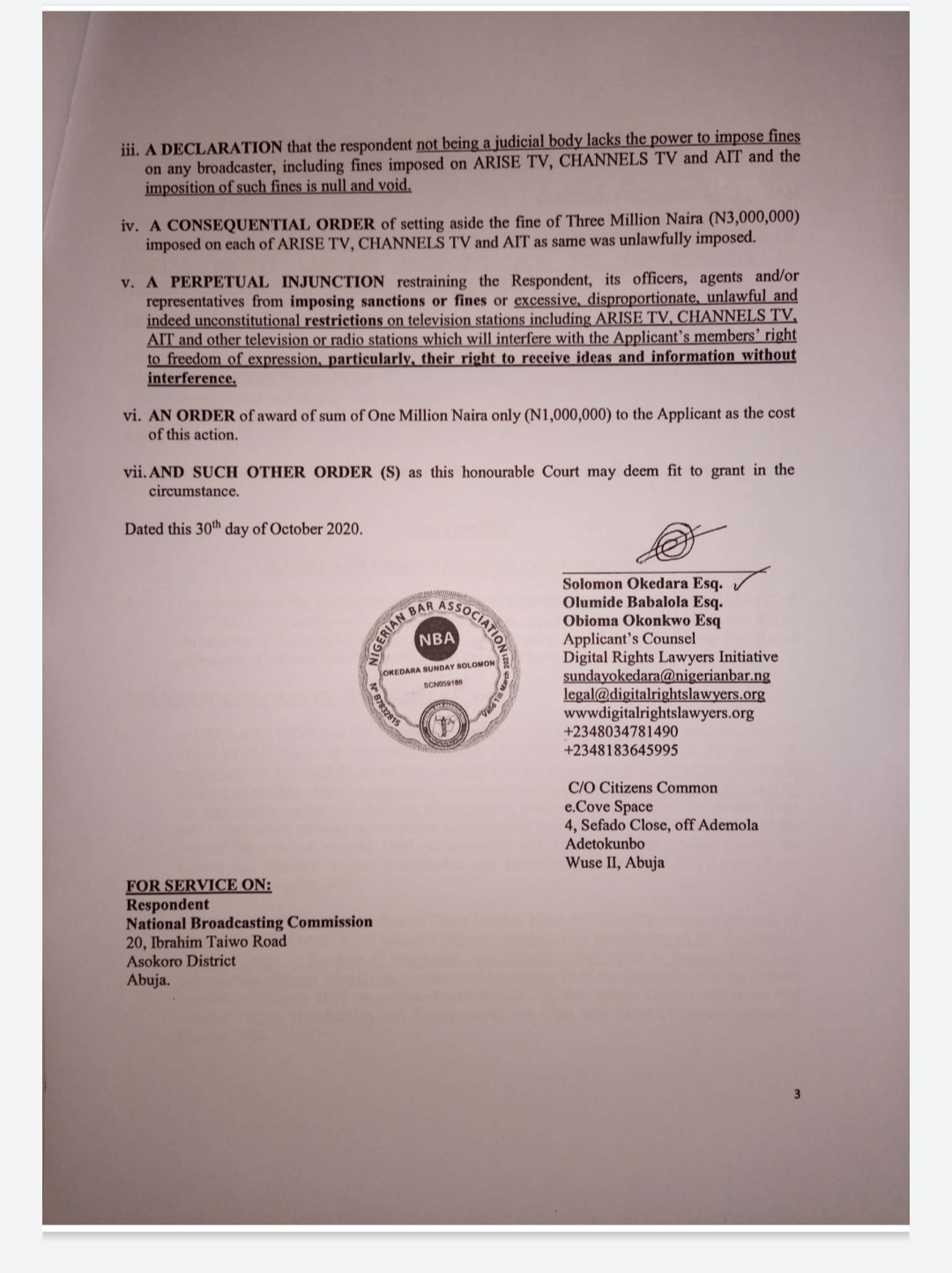

The suit, which was filed by the organization’s lawyers, Solomon Okedara and Olumide Babalola, seeks the following reliefs from the court:

i. A DECLARATION that the Respondent’s arbitrary act of sanctioning and imposing fine of Three Million Naira (N3,000,000) on each of ARISE TV, CHANNELS TV and AIT purportedly in line with Sections 5.6.3 and 5.6.9 of the Nigeria Broadcasting Code creates a chilling or stifling effect on freedom of expression and is likely to interfere with the right of the Applicant’s members to freedom of expression, particularly, their right to receive ideas and information without interference as guaranteed by section 39 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended) and Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Ratification and Enforcement) Act (Cap A9) Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004.

ii. A DECLARATION that the fine of Three Million Naira (N3,000,000) imposed on each of ARISE TV, CHANNELS TV and AIT indeed constitutes an interference to the Applicant’s members’ right to freedom of expression, particularly, their right to receive ideas and information without interference guaranteed by section 39 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended) and Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Ratification and Enforcement) Act (Cap A9) Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004.

iii. A DECLARATION that the respondent not being a judicial body lacks the power to impose fines on any broadcaster, including fines imposed on ARISE TV, CHANNELS TV and AIT and the imposition of such fines is null and void.

iv. A CONSEQUENTIAL ORDER of setting aside the fine of Three Million Naira (N3,000,000) imposed on each of ARISE TV, CHANNELS TV and AIT as same was unlawfully imposed.

v. A PERPETUAL INJUNCTION restraining the Respondent, its officers, agents and/or representatives from imposing sanctions or fines or excessive, disproportionate, unlawful and indeed unconstitutional restrictions on television stations including ARISE TV, CHANNELS TV, AIT and other television or radio stations which will interfere with the Applicant’s members’ right to freedom of expression, particularly, their right to receive ideas and information without interference.

vi. AN ORDER of award of sum of One Million Naira only (N1,000,000) to the Applicant as the cost of this action.

vii. AND SUCH OTHER ORDER (S) as this honourable Court may deem fit to grant in the circumstance.

Speaking, after the suit was filed, Solomon Okedara noted that the protection of the Applicant’s members’ right to receive ideas and information is not just required for proper for their proper development in all facets of life but it is indeed a matter of their fundamental right to freedom of expression which cannot just be toyed with by any person or entity. Okedara further noted that ensuring a free and independent media is not just a matter of discretion of the government or regulatory agency but a mandatory requirement for a democratic society.

by Legalnaija | Oct 28, 2020 | Uncategorized

The World Trade Organization is an intergovernmental organization that is concerned with the regulation of international trade between nations. It was founded on the 1st of January, 1995 and has 165 members.

The WTO was born out of negotiations, and everything the WTO does is the result of negotiations. The bulk of the WTO’s current work comes from the 1986–94 negotiations called the Uruguay Round and earlier negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The WTO is currently the host to new negotiations, under the ‘Doha Development Agenda’ launched in 2001.

Some of its duties include;

– It is an organization for trade opening.

– It is a forum for governments to negotiate trade agreements.

– It is a place for them to settle trade disputes.

– It operates a system of trade rules. Essentially, the WTO is a place where member governments try to sort out the trade problems they face with each other.

Nigeria has been a WTO member since 1 January 1995 and a member of GATT since 18 November 1960. Nigeria, on 9 June 2020, nominated Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala for the post of WTO Director-General to succeed the current Director-General, Mr Roberto Azevêdo, who has announced he stepped down on 31 August 2020.

The nomination period for the 2020 DG selection process ended on 8 July, with eight candidates nominated by their respective governments. On 31 July, the General Council agreed that there would be three stages of consultations with WTO members commencing on 7 September to assess their preferences and to determine which candidate is best placed to attract consensus support.

The General Council Chair announced on 18 September the results of the first round of consultations and the five candidates advancing to the next stage. On 8 October, he announced the results of the second round of consultations and the two candidates advancing to the third round.

Nigeria’s Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is slated to be the first woman & African to lead the institution. However, the US has has refused to support her candidacy. Final outcome will now be decided Nov 9!

by Legalnaija | Oct 26, 2020 | Uncategorized

The Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria is

guided by the fundamental objectives and directive principles of state policy

as contained in Chapter II of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of

Nigeria 1999 (as amended). The most fundamental objective and primary purpose

of any government that is founded on the Constitution shall be the security and

welfare of the people. Accordingly, the Government (including the federal and

state governments) must prioritize the security and welfare of its Citizens at

all times. This is by virtue of the provisions of Section 14(2)(b) of the

Constitution.

It is a fundamental principle of interpretation of

Statutes and the Constitution that sections/provisions of the law are not read

in isolation, but are rather read as a whole. Therefore, when trying to

understand what the drafters of the Constitution intended in Section 14(2)(b)

of the Constitution, it is important to read the said subsection together with

the provisions of the preceding Section 14(1) and 14(2)(a) of the Constitution.

Section 14(1) of the Constitution provides thus:

“Section 14(1) – The Federal

Republic of Nigeria shall be a State based on the principles of democracy and

social justice.”

Section 14(2)(a) and (b) provides thus:-

“Section 14(2) – It is hereby, accordingly,

declared that –

(a) sovereignty belongs to the people of Nigeria from whom government through

this Constitution derives all its powers and authority;

(b) the security and welfare of the

people shall be the primary purpose of government; and

(c) The participation of the people in the government shall be ensured in

accordance with the provisions of this Constitution.”

The marginal note of Section 14 of the Constitution is

termed as “the Government and the people.”

Therefore, a community reading of the entire provisions of Section 14 of the

Constitution (together with the marginal note) evinces the intention of the

framers of the Constitution to vest the sovereignty of the Federal Republic of

Nigeria in the people from which the Government is to derive all its powers and

authority through the Constitution. The importance of the provisions of Section

14(2)(a) of the Constitution is that it makes the Government directly

answerable to the people who donate sovereignty to it. Hence, a direct social

contract is created by virtue of this provision, in which the people donate

power to the Government, and in return, the Government is to perform the

various functions and responsibilities stated in the contractual document: the

Constitution. The chief responsibility of the Nigerian Government by virtue of

this Constitution is the security and welfare of the people.

The precise words of this section of the Constitution implies

that the Nigerian Government (including the federal and state governments) must

be preoccupied and concerned with the security and welfare of the citizens at

every point in time. Any Government that refuses to preoccupy itself with this

primary responsibility of prioritizing the security and welfare of the people

would therefore lack the sovereign backing of the people.

In the same vein, by virtue of the provisions of

Section 14(1) of the Constitution, the Nigerian Government (both federal and

state Governments) must be premised on the principles of democracy and social

justice at all times. Democracy as famously described by Abraham Lincoln is the

Government for the people, of the people and by the people. The intention of

the drafters of the Constitution is more pronounced when the provisions of

Section 14(1) is juxtaposed with the definition of democracy and the provisions

of Section 14(2) of the Constitution which points to the unassailable

conclusion that any Government which is not “for the people” and which cannot

provide security and welfare for its people does not qualify to be a Legitimate

Government as intended by the framers of the Constitution.

The provisions of Section 1(2) of the Constitution lends

further credence to this interpretation.

The said Section 1(2) provides thus:

“The Federal Republic of Nigeria shall

not be governed, nor shall any person or group of persons take control of

the government of Nigeria or any part thereof, except in accordance with the

provisions of the Constitution.” (underlining ours).

The simple and literal meaning of this section of the

precious and organic document called our Constitution is that Nigeria shall

only be governed in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution.

Therefore, any attempt to govern any part of Nigeria in such a way that

deviates from the express words of the Constitution will amount to an

illegality and an unconstitutionality. Hence, any Government which does not pay

credence to the provisions of the Constitution is dabbling in illegality.

It is trite that sovereignty is one of the sine qua non for any legitimate

government. Any Government that does not possess or cannot trace its sovereignty

is at best, a puppet government as it lacks the autonomous quality to operate

as a State strictu sensu.

The fulcrum of this article has been on the

interpretation of Section 14 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of

Nigeria 1999 (as amended). However, it has been argued that the provisions of

Section 14 which falls under Chapter II of the Constitution is non-justiciable

by virtue of the provisions of Section 6(6)(c) of the Constitution which

provides thus:-

“Section 6(6) – The judicial powers

vested in accordance with the foregoing provisions of this section –

(d) Shall not, except as otherwise provided by this Constitution, extend to

any issue or question as to whether any act or omission by any authority or

person or as to whether any law or any judicial decision is in conformity with

the Fundamental objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy set out in

Chapter II of this Constitution;”

This writer submits that the non-justiciability of the

provisions of Chapter II of the Constitution does not render the entirety of

that Chapter otiose or moot. The provisions of Section 6(6)(c) of the

Constitution only serves to prevent the judiciary – the Courts – from enquiring

into the validity of any act or omission done, or not done, pursuant to the

provisions of Chapter II of the Constitution. In other words, the provisions of

that Chapter cannot be enforced or questioned in a Court of law.

However, this does not mean that the provisions of

Chapter II are hereby rendered academic and of no practical purpose. The Courts

are set up to determine civil rights and obligations of Nigerian Citizens.

(Please see Section 6(6)(b) of the Constitution). However, as earlier

established, sovereignty is vested in the people by virtue of the Constitution

and it is through this Constitution that the Government exercise all authority

and powers which it purports to have. It has also been established that

sovereignty is a fundamental element which every government must possess before

it can purport to operate as a state.

Therefore, this writer submits that any Government

which cannot confidently tick all the important boxes contained in Section 14

of the Constitution is an unconstitutional government. For the avoidance of

doubt, any Nigerian Government which cannot boast of:-

a. being based on the principles of

democracy and social justice or which does not listen to the wishes of the

people; and

b. placing premium on the security

of welfare of the people at all times; and

c. allowing the people to directly

participate in the government in accordance with the provisions of the

constitution;

is an illegitimate government and one does not need

the Courts to invoke its judicial powers under Section 6 of the Constitution to

declare it as such. Another fundamental element of statehood (apart from

sovereignty) is equal recognition by other states. A Government which purports to be an

autonomous government needs to be recognized as such by other sovereign

Governments else that Government will not be seen by the international

community as the machinery of the state through which the will of its people is

formulated. Such a Government which is not afforded sovereign status in the

international community will find it difficult protect the interests of its

people.

Therefore, any Nigerian Government which cannot show

that it can confidently secure the lives and properties of citizens within its

territory has no business in parading itself as an autonomous government. In

addition, when such government is notorious for abusing the principles of

fundamental principles of democracy and social justice, such a government

stands the risks of losing its statehood in the international community.

I am Oluwanonso_Esq on Twitter.

by Legalnaija | Oct 23, 2020 | Uncategorized

The Nigerian Electoral system is a work in

progress, and one of its challenges is voter registration and collection of

Permanent Voters Card (PVC). During the last election cycle, Continuous Voter

Registration (CVR) across the country commenced on 27th April, 2017 and ended on

the 31st of August, 2018. Though the exercise lasted for about 16

(Sixteen) months, many stakeholders and citizens called for an extension of the

exercise.

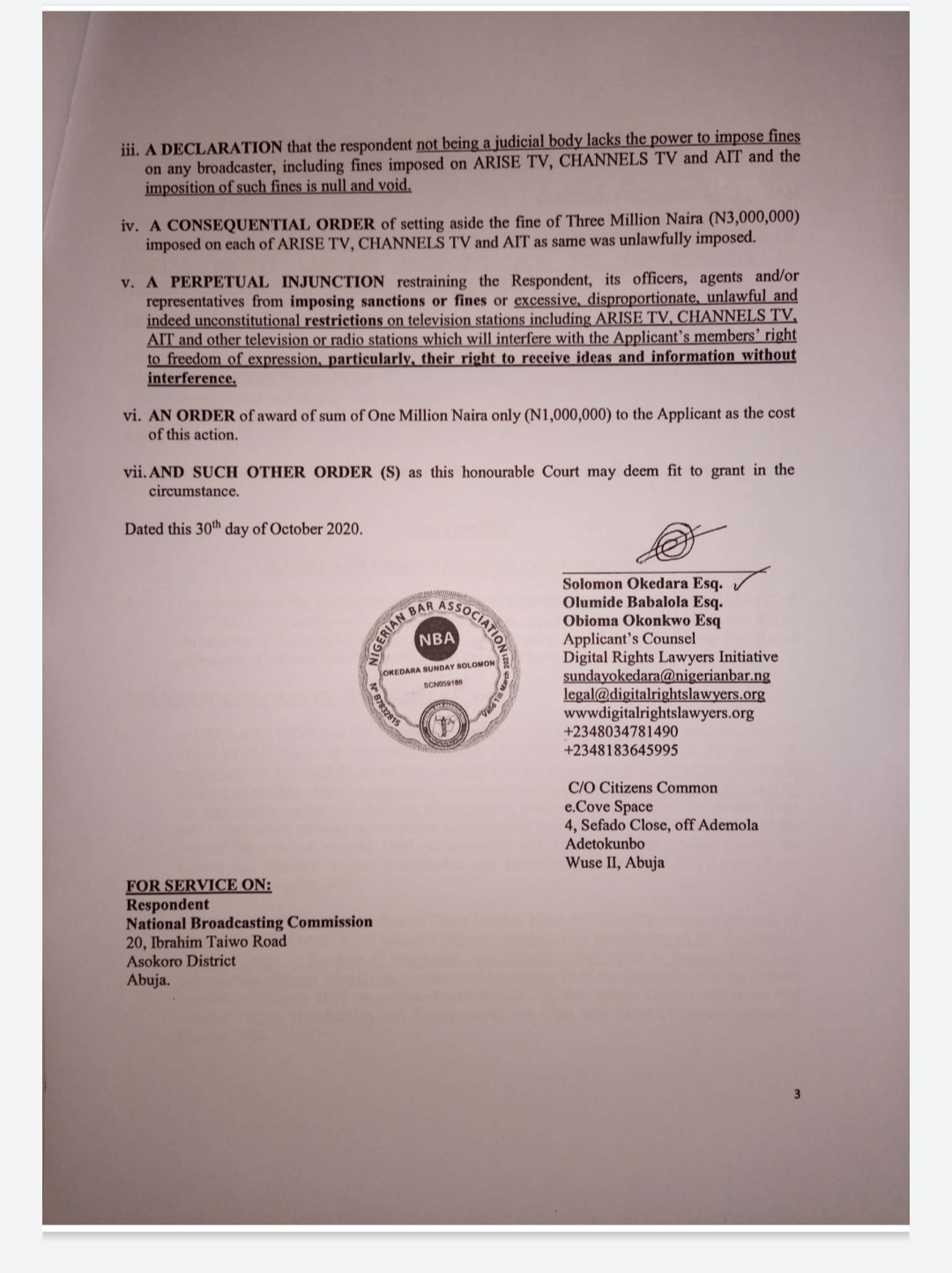

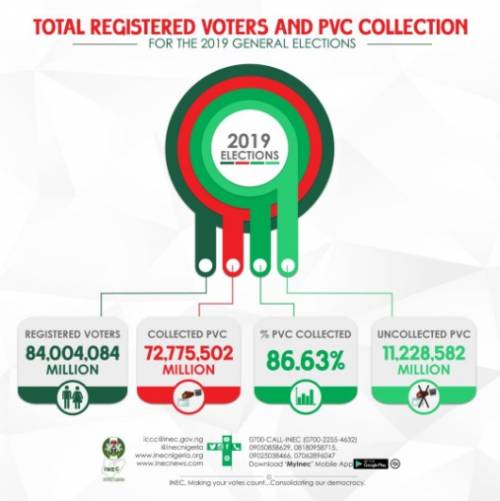

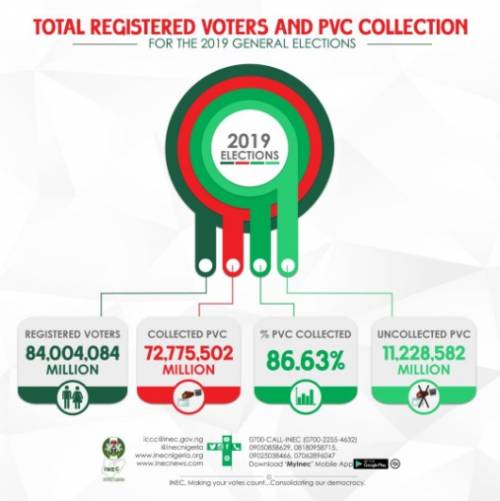

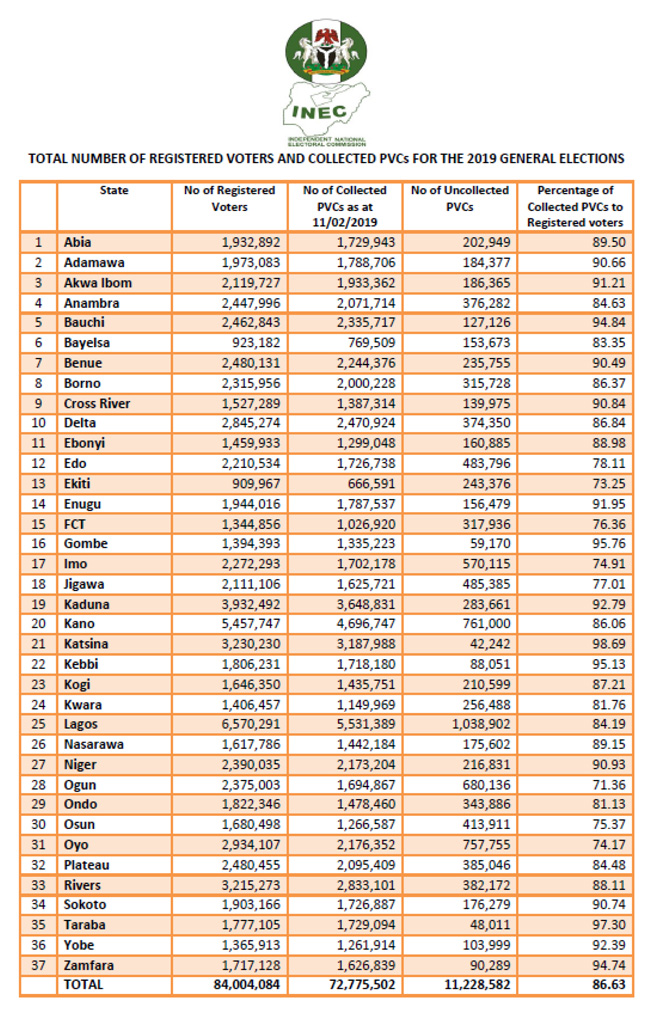

According to the Independent

National Electoral Commission (INEC), as at the 11th of February,

2019, out of the 84,000,484 registered voters, over 11 million registered

voters were yet to collect their PVCs, a figure that represents 13.7% of the

total PVCs produced. Out of this figure, 7,817,905 PVCs were carried over from

the 2014 to 2016 registration exercises, while 3,410,677 are from the last

Continuous Voter Registration (CVR) exercise held between April 2017 and August

2018.

Beginning the process of voter registration

early allows INEC enough time to clean up the provisional register and print

the Permanent Voters Card (PVC) in good time for the general elections. Most

importantly, it allows citizens enough time to be duly registered and obtain

their Permanent Voters Card in order to be eligible to vote. The INEC Chairman

has stated that we are now 848 days from the 2023 Presidential Elections, which

allows INEC 27 months to plan for the election but only about 20 months to

carry out its Continuous Voter Registration, assuming it resumes the exercise

immediately.

If 16 months was not enough time to carry out

a voter registration exercise in 2018, I believe we should be taking advantage

of the remaining 20 months. Moreso, because of the millions of voters who

reached voting age, after the 2019 Elections, and the number of voters who

were left unregistered in 2018, it is safe to assume that INEC has its work cut

out for it as we prepare for the 2023 Elections.

So why hasn’t INEC resumed the Continuous

Voters Registration exercise, despite the promises made in 2018, that the

process will resume immediately after the 2019 elections? Are we already

planning to fail at the 2023 elections?

Please sign this petition for INEC to resume Voter Registration ahead

Please sign this petition for INEC to resume Voter Registration ahead

of the 2023 General Elections http://chng.it/tkzkp2JY via

Change.org

Adedunmade Onibokun

Partner, AOC Legal

dunmadeo@yahoo.com

by Legalnaija | Oct 22, 2020 | Uncategorized

My fellow Nigerians,

The last few days have been pivotal in our desire

for a Nigeria, where justice, equity and fairness are the order of the day,

where our fundamental human rights to life, personal dignity and humane

treatment shall be respected. Our leaders, neighbours and the international

community have heard our call to action.

Our biggest achievements however are we have

shown the world our capacity for demonstrating empathy towards each other,

courage, leadership, fellowship and unity. Over the past few weeks not only did

we take responsibility for the growth of our country but we organized ourselves

in a way never before seen by young Nigerians. Most importantly, we were able

to secure the commitment and action from government and the Nigerian Police to

#EndSARS and #Endpolicebrutality in Nigeria.

However, the events of the last 48hrs has

shown us that we have not achieved our goal, the response of security forces to

the peaceful demonstration of young Nigerians show that the problem is not only

the Special Anti – Robbery Squad but also the need to reform the Nigerian

Police and promote credible and accountable leadership in Nigeria.

The peaceful protests are a start in the right

direction and we must ensure that the legacies of our fellow Nigerians who paid

the ultimate price in our struggle for sustainable governance in Nigeria are

not wasted. That the sacrifice of everyone who participated in the #EndSARS

campaign, sustained injuries and were subject to threats to their lives are not

for nothing.

To achieve this I propose the following –

1.

The #EndSARS Protests

While protests is a

strong way of showing disapproval, as seen from recent events, it is not immune

to manipulation and can easily be turned into a riot. Holding a protest though

the most popular way of showing dissent is only one of the over hundred ways of

non – violent action and I urge young Nigerians to become creative in using the

peaceful protests to send clear messages. Demonstrators should become more

strategic with the protest, they must always be peaceful, organized and not

fall below the recent standards that have been applauded by everyone.

2.

Political Will &

Participation

You will agree with me that political Will is needed to create the type of democracy we want,

however, the political structures of today are in the hands of career

politicians who have led this country since the 70s and 80s and have shown time

and time again that their loyalty is to themselves. It is high time young Nigerians

grab this political structures and we can achieve this by participating

actively in governance and politics. Let us register to vote in huge numbers

and join political parties so we can influence the structures from the inside.

3.

Community Outreach

A lot of

misinformation has been peddled both online and offline. It is our duty to

begin to reach out to stakeholders in our communities and carry them along in

our plans for a better Nigeria. Those touts who are not engaged will be used by

unscrupulous politicians to scuttle any progress that is achieved, so it’s

important that we bring everyone on onboard as well. Like it is said, all

politics is local so we must begin to use our local contacts in asking for accountability

and governance from our leaders.

4.

Facilitators

The #EndSARS movement

has no perceived leadership structure but it has leaders, we successfully crowd

sourced a leadership structure that saw everyone taking responsibility. We had

people like @fkabudu, @moechievous and @adetolaov take up the responsibility of

organizing and in the process built a national legal aid structure. We had

volunteers in teams such as legal, emergency services, security, welfare and

others.

I want to urge everyone

to continue to lead by example. We are all stakeholders in the clamour for a

better Nigeria and the victory of one is a victory for all.

5.

Engagement

We cannot stop

engaging with stakeholders and government representatives as we have been doing

recently. In fact, we must increase our level of engagement at this time. Contact

any and all government representatives you know and engage them on their

respective deliverables. We must monitor and supervise the government and our

elected officials to ensure that they are carrying out their duties and

functions satisfactorily.

In the words of Patrick Lumumba, “The day Nigeria wakes up, Africa will never

be the same again”. Young Nigerians

have woken up and our struggle is not only for a better Nigeria but for a greater

Africa. The world is counting on us, our African brothers and Sisters are in

solidarity with us and it is time we show the leadership that is lacking in our

polity.

Thank you for reading. God bless the Federal Republic of Nigeria. #EndSARS

Adedunmade is a Nigerian Lawyer, Author and

Blogger. Youcan contact him via @adedunmade on social media and via dunmadeo@yahoo.com

by Legalnaija | Oct 21, 2020 | Uncategorized

If you are a friend, visitor

or lover of Nigeria, you are definitely aware of what is going on in the

country at the moment. Young Nigerians who signified their discontent with

police brutality through the #EndSARS hashtag had been staging peaceful

protests all over the country until recently, when the process led to loss of

lives and what is now being described as a full scale massacre of innocent demonstrators,

perpetrated by state agents and security forces.

Yesterday, 20th

of October, 2020, which is now called #BlackTuesday, the Nigerian government ordered

soldiers to open fire on demonstrators, an action which has now resulted into

the loss of tens of lives and also destruction of both public and private

property. Social Media is currently awash with videos and photos of security

agents killing unharmed citizens, some while the citizens were seen fleeing for

their lives.

So why should President

Buhari be impeached? If you are familiar with the antecedents of this

government, you will agree that they have cracked down hard on dissent and have

regarded any questions from the people as a direct challenge to their

administration. Take a cue from Sowore, who called for a revolution in the country

and how his fundamental human right were breached by State Agents and the Attorney

– General of the Federation was heard in several interviews saying that any

attempt to replace the government by unconstitutional means will be met with

force. It is evident that this government is incapable of providing the kind of

leadership that this country needs going forward, for instance since the deaths

of Nigerian youths, the President has failed, refused and neglected to address

the nation, despite a call from all areas of the country and most recently by

the National Assembly. President Buhari still remains silent.

A look at our constitutional

provisions, particularly Section 143 (2) states that a President can be impeached

whenever a notice of any allegation in writing signed by not less than

one-third of the members of the National Assembly:- (a) is presented to the

President of the Senate; (b) stating that the holder of the office of President

or Vice-President is guilty of gross misconduct in the performance of the

functions of his office, detailed particulars of which shall be specified.

The above paragraph now begs

the question what can be described as “gross misconduct” under the

constitution? The Supreme Court in Inakoju

& Ors vs. Adeleke & Ors (2007) LPELR – 1510 SC, describes it to

mean “a grave violation or breach of the provisions of the Constitution or a

misconduct of such nature, as amounts in the opinion of the National Assembly

to be a gross violation.

What has President Buhari

done that may be seen as a gross violation of the Constitution?

1. President

Buhari breached the fundamental rights of Nigerians when he ordered the military

to shoot at citizens who were demonstrating for an end to police brutality, in

breach of Section 33 of the Constitution, which provides that; Every person has

a right to life, and no one shall be deprived intentionally of his life, save

in execution of the sentence of a court in respect of a criminal offence of

which he has been found guilty in Nigeria.

2. President

Buhari breached the rights of Nigerian Citizens to lawful assembly as provided

in Section 40 of the Constitution, when he ordered security operatives to disperse

lawful and peaceful demonstrators through violence.

From the above, it is

evident that by President Buhari ordering and/or condoning the shooting of

unharmed demonstrators, the President has directed the very killing of the

citizens he swore to protect and if this is not an impeachable offence, I don’t

know what is.

Adedunmade Onibokun

by Legalnaija | Oct 16, 2020 | Uncategorized

On Tuesday, 13th October 2020, the Federal

High Court, delivered a ruling, setting aside the Garnishee Order Nisi made

against the Central Bank of Nigeria in Suit No: FHC/ABJ/CS/563/2020 between Bendu

Peter Services Nigeria Limited & Anor V. Guaranty Trust Bank Plc & Anor.

Bendu Peters Services Nigeria Limited, instituted a

suit before the High Court of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, challenging

the actions of the Guaranty Trust Bank in freezing, suspending and refusing to

allow cash withdrawal from her account when requested.

On the 23rd of March 2020, the High Court

delivered its judgment and amongst the declaratory reliefs and, consequential

orders granted in favour of the Plaintiff, the court also awarded a judgment

sum of N24,282,017,249.00 (Twenty-Four Billion, Two Hundred and Eighty-Two

Million, Seventeen Thousand, Two Hundred and Forty-Nine Naira) against Guaranty

Trust Bank.

In a bid to reap the fruits of the judgment gotten at

the High Court, Bendu Peters Services Nigeria Limited, instituted garnishee proceedings

at the Federal High Court, Abuja and sought for the immediate attachment of the

sum belonging to Guaranty Trust Bank Plc in the custody of the Central Bank of

Nigeria.

In compliance to the Garnishee Order Nisi, ordering

the Central Bank of Nigeria to appear in court and to disclose by evidence,

reasons why the Order Nisi should not be made absolute against it, in which

circumstance, the counsel to the Central Bank of Nigeria, O. M. Atoyebi, SAN and

other counsel in the matter now before the Federal High Court Abuja, filed all

necessary processes alongside an objection, wherein they also sought the order

of court to set aside the entire proceedings and on the part of the Bank in

particular, counsel sought the order of court to set aside the Order Nisi made

against the Bank.

The court in

considering the application filed before it, held that the failure of the Plaintiff

now Judgment Creditor at the Federal High Court to disclose the pendency of an

application for the stay of execution of the Judgment obtained from the High

Court of the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja on the 23rd of March

2020, deprived the court of its jurisdiction to entertain the garnishee

proceedings and on that rationale, the court vacated the Order Nisi made

against the Central Bank of Nigeria and consequently dismissed the action in

its entirety.

![Visas And Permits Under The Nigerian Immigration Law[1] | KHALID ABDULKAREEM](https://legalnaija.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/khalid-visa2.png)