by Legalnaija | May 8, 2021 | Uncategorized

Is The Law Truly What The Court Says? | Samuel Edeh

ABSTRACT

There is no authoritative definition of law and most certainly, there will never be. Any attempt at giving a universal acceptable definition of law will be akin to forcing a camel through the eye of the needle or forcing a fish to climb a tree. Consequently, theories of law are founded to establish an understanding of the nature of law. These theories allow us to attempt the question as to what is law and what the law ought to be. Now, there are schools of jurisprudence which influences the answer. These theories of jurisprudence include, but not limited to, the positivist theory, realist theory, natural law theory, historical theory etc. The positivist believes law to be nothing more pretentious than what a recognized sovereign authority has enacted. For instance, Section 4 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria vested the National Assembly with the powers to make laws for the Federation. It follows, therefore, that where the constitutional procedure of law making is strictly adhered to, any law emanating therefrom is valid, nothing more, nothing less. The question as to whether it is just or unjust is inconsequential. On the other hand, the realist theory is against this view. For them, what the court says in resolving disputes is the law. In other words, the decisions of courts stand as the law. Therefore, the aim and objective of this paper is simple. It is to demonstrate that the decision of the court stands as the law – and not the provisions of statutes. By so doing, this paper will also show landmark cases wherein the court took the view of the realist. As a result, this topic will be doctrinal in nature, in other words, a desk-based or library-based research. It will rely on available literature and numerous cases on the topic. The topic will also rely on secondary sources, considering that most of the materials in this area of law are secondary sources.

INTRODUCTION

In order to have better understanding of law, it is apt to properly examine the concept called jurisprudence. Jurisprudence is a vibrant discourse in the study of law and its definition abounds.1 In fact, it is as big as law — and bigger.2 The term jurisprudence derives from Latin word jurisprudentia which according to the English Oxford Dictionary means knowledge of or skill in law. Juris means law and prudentia means science or a systematic body of knowledge. Thus etymologically jurisprudence means science of law, the science which treats of human laws in general i.e. philosophy of law. From the Romans, as we learn from Cicero, the study of law must be derived from the depths of philosophy and involves an examination of the human mind and of the human society from which rules of positive law are distilled.

There is no convincing definition of jurisprudence. Dias expresses the same opinion: the answer to the question, what is jurisprudence? is that it means pretty much whatever anyone wants it to mean. But Llewellyn believed jurisprudence to mean:

Any careful and sustained thinking about any phase of things legal, if the thinking seeks to reach beyond the practical solution of an immediate problem in hand. Jurisprudence thus includes any type at all of honest and thoughtful generalization in the field of the legal.

However, the study of jurisprudence in modern legal academia is imperative. It helps the judges in ascertaining the true meanings of the law passed by the legislature by providing the rules of interpretation. Jurisprudence does not teach law, but an examination of the law. This is the big fact in litigation. Armed with the knowledge of jurisprudence the lawyer can think beyond the relish of that statute. It is the critical thinking of what law ought to be that initiates law reforms in society. Otherwise, society will run into danger when we have static laws that draw no good and development.

Conclusively, this overview of jurisprudential purposes is not exhaustive. It can be extended. The conclusion from this survey is clear. Jurisprudence is not fixed. Undeniably, jurisprudential activities reflect countless purposes, they vary over time, they sometimes appear to controvert each other, they are not always possible to describe in detail, and they are occasionally completely implicit.

THE REALIST SCHOOL OF JURISPRUDENCE

An alternative theory to both positivism⁶ and naturalism is legal realism. Legal realists are more concerned with “law in action” rather than with “law in statute books. Legal realist holds the view that law is practical and pragmatic. It is based on the belief that judges neither do nor should decide cases formalistically. Law is not, as the positivist claimed, as system of rules that is clear, concise, consistent and complete. To a realist, statutes and case law are only sources of law, until a judge interprets and reaches a decision in a dispute and state what the law is. A major forerunner of this school of thought is Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. In his famous essay Holmes wrote:

The prophecies of what the courts will do in fact and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by law… We must reject the view of text writers who tell us that law is something different from what is decided by the courts of Massachusetts or England, that it is a system of reason that is a deduction from principles of ethics and admitted axioms or what not, which may or may not coincide with decisions.

The above means that the pronouncement of the court is the law. Therefore, a law that has not be examined in a court is no law, not even the provisions in the statutes. Some proponent of this school believe that there should be no deviation from judicial precedents because it is the law, whereas the second group believe that precedents should not be worshipped and that activist judge can deviate from already made precedents.

Conclusively, for the legal realist, there is always a lacuna between what is and what ought to be. There are interested in what is as it has been pronounced by the court and nothing more pretentious. According to them certainty of the law is a myth until it is addressed in court.

IS THE LAW TRULY WHAT THE COURT SAYS?

In applying the proposition of Oliver Wendell Holmes and other realist proponents, it is my humbly view that in Nigeria and other democratic countries, like the United States, the law is truly the verdict of the court and the provisions in the statute books are just skeleton until given flesh and life-breath by the court.

In Donoghue v Stevenson 3, the Neighbour Principle was formulated by the House of Lords. Here, a manufacturer of ginger beer sold ginger beer in an opaque bottle to a retailer. A boy bought a bottle of the ginger beer from the retailer and treated his girlfriend to its contents. The girl alleged that that she suffered some injury as a result of seeing and drinking the contaminated contents of the beer manufactured by the defendant. The ginger beer, in fact, contained decomposed remains of a snail. Since she had not, herself, been in a contractual relationship with the proprietor, she could not sue him, and she was then forced to sue the respondent manufacturers of the ginger beer. The boy, on his part, could not sue anyone because he did not suffer any injury. The Scottish Court held that they could not find any legal connection between the girl and the manufactures. But when the case got to the House of Lords, a majority of the court held that the manufacturer owed her a duty to take care that the bottle did not contain noxious matter and that he would be liable if that duty was broken. In holding the manufacturer liable the court made tortuous liability to exist in the absence of privity of contract. According to Lord Atkins:

The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyers question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who then, in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be — persons who are so closely and directly affected by my acts that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts of omission which are called in question.

From the above foregoing, the court propounded a new law and applied the newly propounded law to the instant case above. This newly promulgated law is that a person can be liable for tortuous act in the absence of any kind of relationship. It therefore means that a consumer of butter in Nigeria can maintain an action against a Ghanaian manufacturer for breach of the neighbour principle even when there is no contractual relationship between them. This principle has been replicated in some many Nigerian judicial decisions.

The Strict Liability Rule is not as result of legislative framework but as a pronouncement of the court in Ryland v Fletcher.4 Also this decision has been replicated in some many Nigerian judicial decisions.5 The defendant, in this case, employed independent employed independent contractors to construct a reservoir on their land. While carrying out the work, the independent contractors discovered some disused shaft beneath the site of the reservoir which connected their land with plaintiffs mine. They negligently did not block them up because the shafts appeared to be filled with sand. When the reservoir was completed and filled with water, the water escaped down the shafts and flooded the mine of the plaintiffs. The defendants were held liable under the rule of law established by Blackburn J:

We think that the true rule of law is that the person who, for his own purposes brings on his lands and collects and keeps there anything likely to do mischief if it escapes must keep it at his peril and if he does not do so, is prima facie answerable for all the damage which is the natural consequence of its escape.

Further, the belief that law is the prophecies of the court was ventilated in the epoch-making judgment of the United States Supreme Court in Obergefell v Hodges6 which legalized same- sex marriage in all 50 States in America. This case marked a defining moment in the history of the United States. It successfully brought to end many years of raging debates over the legality of or otherwise of gay marriage in the United States. The Supreme Court did not base its decision on any statute/law. The Court employed the Individual Autonomy Principle to legalize gay marriage. Justice Kennedy who led the majority judgment of 5-4 has this to say:

Expanding a right suddenly and dramatically is likely to require tearing it up from its roots… This free — wheeling notion of individual autonomy echoes nothing so much as the general right of an individual to be free in his person and in his power to contract in relation to his own labour.

He further stated as follows:

If you are among the many Americans of whatever sexual orientation — who favour expanding same — sex marriage, by all means celebrate todays decision. Celebrate the achievement of a desired goal. Celebrate the opportunity for a new expression of commitment to a partner. Celebrate the availability of new benefits. But do not celebrate the constitution. It had nothing to do with it.

The above dicta clear shows that the decision has not nothing to do with the Constitution but enhances the view that the law is nothing more but the prophecies of the court.

Having meticulously considered the application of the realist theory in foreign cases, it is also mandatory, for the purpose of elucidation, to establish its existence in our legal jurisprudence. Under the Nigerian criminal jurisprudence, a defendant may claim that a certain set of facts or events happened which ought to exonerate him from criminal liability. And such eventualities are called defences. The law is very much settled that any defence to which an accused person is, on the evidence entitled to, should be considered for what it is worth however stupid or unreasonable it might appear to the court. However, from the clear wording of section 318 of the Criminal Code Act it is highly possible to submit that where the defence of provocation succeeds in a charge of murder, the defendant is to be convicted for manslaughter. He is not to be discharged and acquitted. This is settled law.

But, the Supreme Court in Shande v. The State7 made a u-turn. The appellant caused the death of the deceased (her husbands lover). She poured kerosene on the deceased and lit her on fire. She was charged with culpable homicide under the Penal Code Act. She pleaded provocation. She was convicted at the trial court and her conviction was upheld by the Court of Appeal, hence her appeal to the Supreme Court. After holding that the defence of provocation suffices, the Supreme Court went ahead to discharge and acquit her. This is against the position that provocation as a defence does not excuse the offence of murder. And it appears that the Supreme Court had jettisoned such laid down principles of law.

Further, the decision in Rt. Hon. Amaechi v INEC & Ors8 re-enforces our claim that the law is what the court says and nothing more. In 2007, the appellant (henceforth Amaechi) contested in the primary election for the gubernatorial candidate of Peoples Democratic Party (henceforth PDP). Amaechi emerged as the winner of the PDP primaries. His name was transmitted to the Independent National Electoral Commission (henceforth INEC) as the gubernatorial candidate of PDP. Sometime thereafter, Amaechis name was substituted with that of Omehia (who did not event participate in the primary election). Dissatisfied, Amaechi approached the Federal High Court seeking inter alia a declaration that he remained the lawful candidate of PDP for the election because no cogent and verifiable reason was given by PDP for the substitution of his name with that of Omehia as provided under 34(2) of the Electoral Act 2006. The Federal High Court upheld the substitution. Amaechi appealed to the Court of Appeal. Before the appeal was heard, Amaechi was expelled from PDP. On this note, PDP and INEC asked that the Court of Appeal to struck out the appeal on the ground that the Court no longer had the jurisdiction to her the appeal as a result of the expulsion of Amaechi from PDP. The appeal was struck out. Dissatisfied Amaechi appealed to the Supreme Court. But before the Supreme Court heard the appeal on its merit, elections have been concluded in Rivers State and Omehia was declared the winner. And having held that Amaechis name was unlawfully substituted, the Supreme Court was faced with difficulties as to reliefs entitled to Amaechi bearing in mind that election has been held and on the other hand, Amaechi never contested for the gubernatorial election. The central issue was: whether to declare a person who never contested for an election (gubernatorial) winner; which on the other hand is against the spirit of the Electoral Act, 2006. In his augment in the brief filed for PDP, J.K Gadzama SAN argued that Amaechi who had not contested the election could not be declared the winner. He stated that such a declaration would amount to a negation of democratic practice. Adesola Oguntade JSC held as follows:

Am I now to say that although Amaechi has won his case, he should go home empty- handed because elections had been conducted into the office? That is not the way of the court. A court must shy away from submitting itself to the constraining bind of technicalities… it is futile to merely declare that it was Amaechi and not Omehia that was the candidate of the PDP. What benefit will such a declaration confer on Amaechi?

From the above, it follows, therefore, that there may be circumstances where a person who never contested in an election could be declared the winner as was decided above. This led to a jurisprudential war in the Nigerian legal system. The National Assembly did not admire this trend in electoral matters. As a result, they caused an amendment to be made in 2010 to the Electoral Act of 2006. This amendment added a new provision to the Act. It added section 141. It provides as follows: An election tribunal or court shall not under any circumstance declare any person a winner at an election in which such a person has not fully participated in all the stages of the said election.

Hence, if Amaechis case was to be re-litigated under the above provision, he would not have been declared the winner of the election. It is the duty of the legislature, of course, to enact laws for the country. However, it remains the duty of the courts to interpret those laws made by the legislature and a law, as least to a realist, can never by anything other than the prophecies of what the courts will do in fact and nothing more pretentious.

In Gwede v Independent National Electoral Commission9, the Supreme Court was confronted with a case having similar facts with that of Amaechis case because it involves unlawful substitution too. The 2nd respondent, Akpodiete won the primary election of DPP for Ughelli North Constituency II, Delta State. He later withdrew from the election in writing consequent upon which his two-million-naira deposit was refunded to him. DPP substituted him with the appellant and it was published by INEC. Subsequently, INEC substituted the appellant with the 2nd respondent. The appellant brought an action at the Federal High Court challenging the substitution. The Court declined jurisdiction. On appeal to the Court of Appeal, it was held that the substitution of the appellant was unlawful and dismissed all the reliefs sought by the appellant. On further appeal to the Supreme Court, the court in its considered judgment on 24 October 2014 affirmed the candidacy of the appellant but was again faced with the appropriate relief to grant. The Court escaped the handcuffs of section 141 and ordered the certificate of return be issued to the appellant.

The above clearly shows that the decision of the court on this issue is the law and not the provisions of the Act made by the lawmakers. Despite the subsequently amendment of the Electoral Act, the court still went ahead to deviate from such provision. It applied its previous decision (Amachis case) which the purported amendment has abrogated.

In property law, our court has made a significant rule of law on proof of ownership of land. Before the case of Idudun v Okomagba,10 there was dearth or no provision for proof of ownership of land in our statute books. The above case formulated the Proof of Ownership Rule. Thus, a person who is seeking declaration of title to a disputed land, can succeed by proving any or a combination of the following five ways: (1) by traditional evidence (2) by acts of selling, leasing, renting out all or part of the land or far on it or on portion of it (4) by acts of long possession and enjoyment of the land (5) by proof of possession of connected or adjacent land in circumstances rendering it probable that the owner of such connected or adjacent land would, in addition, be the owner of the land in dispute.

On national security and interest, our court has made a judicial pronouncement to this effect. And which is now the law. In Dokub-Asari v Federal Republic of Nigeria, the Supreme Court per Muhammed JSC (CJN Rtd) had the following to say:

Where national security is threatened or there is real likelihood of its being threatened, human rights or individual rights of those responsible take second place. Human right or individual rights must be suspended until national security can be protected or taken care of. This is not anything new. The corporate existence of Nigeria as a united, harmonious, indivisible and indissoluble sovereign nation is certainly greater than any citizens liberty or right. Once the security of this nation is in jeopardy and it survives in pieces rather than in peace, the individual liberty or right may not even exist.

The above declaration simply means that the nations security cannot be sacrificed on the altar of individual rights and rule of law. It even appears that the legislature cannot make any law where the individual right of any individual will supersede that of national interest. It is on the basis of this verdict that the Buharis administration is unwilling to release Col. Sambo Dasuki (erstwhile National Security Adverse) and El-Zakzaky (the leader of the Shiite Islamic Movement of Nigeria). President Buhari, while speaking on the 2018 Annual General Conference of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) revalidated the verdict when he said:

Our apex court has had cause to adopt a position on this issue and it is now a matter of judicial recognition that; where national security and public interest are threatened or there is a likelihood of their being threatened, the individual rights of those allegedly responsible must take second place, in favour of the greater good of society.

This is recognition by the executive arm, hence, the law.

There are sometimes where the law will be uncertain, contentious and controversial. It is not the legislature that will clear the contentious matter. It is the court. On the 30 June 2017, the Supreme Court of Nigeria in Skye Bank Plc v Iwu was called upon to interpret the constitutional provisions below. It relates to the appellate jurisdiction of the Court of Appeal over the decisions of the National Industrial Court which was before now shrouded in deep controversy. The constitution under section 243(3) (4) provides:

(2) An appeal shall lie from the decision of the National Industrial Court as of right to the Court of Appeal on questions of fundamental rights as contained in Chapter IV of this Constitution as it relates to matters upon which the National Industrial Court has jurisdiction.

(3) An Appeal shall only lie from the decision of the National Industrial Court to the Court of Appeal as may be prescribed by an Act of the National Assembly ….

The above simply means an appeal emanating from the decision of the National Industrial Court shall lie to the Court to Appeal as of right where it borders of fundamental human rights provisions under the constitution and an appeal shall lie from the decisions of the National Industrial Court to Court of Appeal as may be prescribed by an Act of National Assembly. But the Supreme Court disregarded these provisions. Per Mary Peter-Odili JSC has this to say: [T]he appellate jurisdiction of the Court of Appeal is not foreclosed within matters only related to fundamental right, rather, the appeals from the National Industrial Court all can go on appeal to the Court of Appeal as of right… Again, Per Clara Bata Ogunbiyi JSC, held: I hold the firm view that all decisions of the National Industrial Court are subject to the review of the Court of Appeal.

The foregoing vividly shows that the court has a choice between alternative meaning of the provisions of a law and it may choose to follow it or reach the decision it wishes.

CONCLUSION

This work has done three basic things. First, it made a critical appraisal of jurisprudence as an imperative study in law. Second, it introduced the realist approach from foreign dimension15. And third, it applied it to our contemporary Nigeria. Law is best described as a complex of rules and reactions emanating from legislative direction, native culture, executive actions and public realities, operating either jointly or independently, but they all have little effect on what judges actually do in Nigeria.

Finally, the duty of a judge is not always a pure deductive reasoning and unbending application of the law to the case he has to decide, because in many cases, the law is neither definite nor satisfactory. I shall conclude this paper by saying that law means no more than decisions of judges. Law is best depicted by what happens in court. In other words, the provision of statues does not; and cannot disclose what courts will do when actual disputes call for determination. For Llewellyn, the paper rules or the pretty playthings have little effect on what judges actually do. As replicated above, the law, in my view, is, always been restricted to and will never cease to be restricted to only judicial pronouncements.

References:

- H.H Mensah Jurisprudential Aspects of Law and Punishment in Nigeria [1996] (38) (184) Journal of the India Law Institute; F.S.C Northropt Contemporary Jurisprudence and International Law [1952] (51) The Yale Law Journal 5; <https://www.marrian-webster.com/dictionary/jurisprudence> Accessed 11 May 2019;

- Karl Nickerson Llewellyn Jurisprudence (1961) 373 cited in Ese Malemi The Nigerian Legal Method: The Theories of Law (Lagos: Princeton Publishing Co Ltd) 18.

- [1932] A.C. 562.

- [1865] 3 H.&C. 774; 159 E.R. 737 (Court of Exchequer).

- In Oladehin v Continental Textile Mills Ltd [1975] 11 SC 155, the defendants were held liable for the escape of industrial waste water which damaged the plaintiffs house. See also Shell Pet. Dev. Co (Nig) Ltd v Amaro [2000] 10 NWLR (Pt 675) 248; Machine Umudje & Anors v Shell [1975] 9-11 SC. 155 at 172; NEPA v Alli [1992] 8 NWLR (Pt 259) 279.

- 576 U.S. — (2015).

- [2005] 40 WRN 145; [2005] 12 NWLR (Pt 939) 301 (SC).

- (2008) 5 NWLR (Pt 1080) (SC).

- (2014) 18 NWLR (Pt 1438) 56 (SC).

- [1976] 9-10 SC, Page 227 at 248.

- . E. Samuel Chukwuemeka [2020] Major Theories of Law Explained; <https://bscholarly.com/schools-of-thought-in-law/> Accessed 11 May 2021;

by Legalnaija | May 8, 2021 | Uncategorized

Title: Babalola’s Law Dictionary Of Judicially Defined Words And Phrases (2nd Edition)

Editor: Olumide Babalola

About

Babalola’s Law Dictionary Of Judicially Defined Words And Phrases (2nd Edition) lists over 3300 definitions and cites over 5000 cases. The Dictionary remains a must have for every lawyer, law firm and law student.

Cost: N5,000

Order Link: https://legalnaija.com/product/babalolas-law-dictionary-2nd-edition/

by Legalnaija | May 8, 2021 | Uncategorized

Title: International Arbitration Law And Practice: The Practitioner’s Perspective

Editor: Tolu Aderemi

About

The Practitioners Perspective” is one book every arbitration practitioner or student should have.

The Book is a compendium of scholarly papers that focus on contemporary topics which will deepen the practice of arbitration; whether at a junior or mid-Senior level. This book is a valuable resource tool for Arbitration Practitioners and is a welcome contribution to the body of knowledge on the topic in Nigeria.

Cost: N10,000

Order Link: https://legalnaija.com/product/international-arbitration-law-and-practice-the-practitioners-perspective/

by Legalnaija | May 8, 2021 | Uncategorized

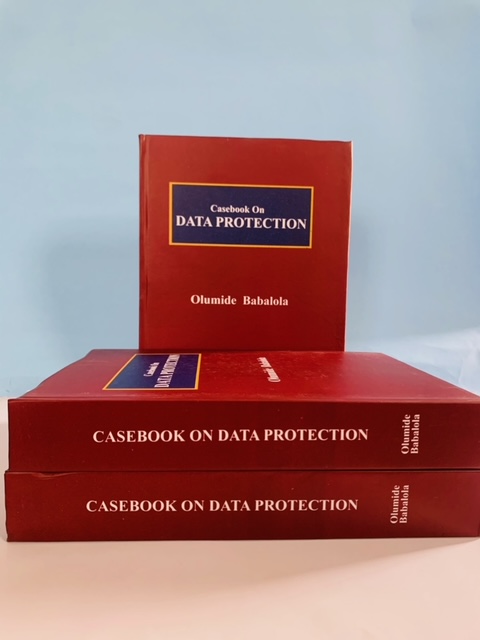

Title: Casebook On Data Protection

Author: Olumide Babalola

About

The book is divided into fourteen chapters. After an introduction that traces the brief history of data protection in Nigeria, separate chapters are devoted to Definitions, Relationship with other rights; Principles of Data Protection; Exceptions and Derogation; Employment Data; Sensitive Data; Transfer of Data to a Foreign Country; Liability of Data Controllers; Data Subject’s Rights; Data Breach; Remedies; Data Property Rights; Supervisory Authority and Appendices that feature the Nigeria Data Protection Regulation and the NDPR Implementation Framework.

Cost: N20,000

Order Link: https://legalnaija.com/product/metamorphosis-tales-by-a-lawyer-girl/

by Legalnaija | May 8, 2021 | Uncategorized

*NBA SECTION ON PUBLIC INTEREST AND DEVELOPMENT LAW ANNUAL CONFERENCE: INVITATION TO PARTICIPATE

Dear Colleagues,

You are specially invited to participate in the Annual Conference of the Section on Public Interest and Development Law of the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA-SPIDEL), which will take place from the 23rd -26th May 2021 at the Jogor Event Centre Ibadan, Oyo State. The theme of the conference is *”The Role of Public Interest in Governance in Nigeria.”*

Kindly register through this link http://nbaspidel.ng/nba-spidel-conference/.

Also, attached is a copy of the letter from the Chairman of the SPIDEL Conference Planning Committee – M. O Ubani Esq., detailing amongst other information, the various sub-topics for discourse, array of speakers, list of topclass hotels at discounted rates, membership information etc.

Be assured that the topics of discourse, array of speakers, serene environment will make this year’s NBA-SPIDEL conference a memorable one.

*Dr. Rapulu Nduka*

Publicity Secretary,

Nigerian Bar Association

by Legalnaija | May 5, 2021 | Uncategorized

The world of sport has fast become a billion-dollar entity, morphing from a mere recreational activity to a financial and economic haven. In its own right, sporting activities account for over 3.7% of the aggregate GNP of the twenty-eight EU states. It is also responsible for over 3% of world trade. It employs fifteen million people in the EU, which is about 5.4% of the entire European labor force. In December 2020, NBA superstar Giannis Antetokounmpo agreed to sign a five-year contract extension with the Milwaukee Bucks worth $228.2 million, in what is the largest deal in NBA history today[1]. Barcelona FC conceded in January 2021 that Lionel Messi indeed earned $167 million a year on a 4-year contract he signed in 2017[2].

Evidently, sport is now bigger than it has ever been, in terms of its lucrativeness and the human resource it employs. It is only natural that in an industry with so much money and people, there would exist a barrage of laws. Although there is no defined and distinct ‘sports law’, it is governed by the basic principles found in our civil and criminal laws.

Arbitration is the primary dispute resolution mechanism employed in sport, with the Court of Arbitration for Sports (CAS) the apex Court for this purpose. The CAS recently overturned the UEFA’s club financial control body (CFCB) decision banning Manchester City FC based on allegations that the club is involved in serious breaches of financial fair play regulations. Recent trends in sports have shown that intellectually property is increasingly regarded as a major source of value and revenue and is thereby heavily guarded. This article focuses on these intellectual property considerations in sports law.

IMPORTANCE

Intellectual Property Rights herein referred to as ‘IPRs” play a massive role in the world of sports, especially in terms of copyright and trademarks. This is because they enable the protection of rights and in this regard, sports branding and marketing, which in turn boosts the successful commercialization of Sports events; major sport events like the Olympic games, the FIFA World Cup, WrestleMania among others are built around IPRs.

One could argue that without the IPRs, these events would not hold. Simply because, nobody wants to pay a ton of money to sponsor sports teams, athletes or events, and not have rights to safeguard such investments. IPRs is the recognized law which breeds confidence in investors or sponsors to part with money and invest in sports because they know such rights, will be legally exploitable and also enforceable in cases of breach. IPRs are not only of importance to sponsors but also to athletes, organizations and personalities.

In marketing sports events, IPRs are important for the aforementioned reasons. The issues with marketing sports events in most common law jurisdictions is the fact that a sporting event as a whole cannot be protected, “A spectacle cannot be owned in any ordinary sense of that word.”[3] This means that a sporting event is legally not a property that can be protected on its own rights. What happens therefore in practice is, potential marketers and investors in sporting events would have to focus on properties within the event which can be legally protected.

This element further raises the level of importance attached to trademarks and copyright. Special note should be taken on the importance of registered ‘domain names’ for sports bodies who use this domain names to promote, market and commercialize sporting events, organizations and personalities. In practice, these domain names serve as quasi trademarks and most times, it gives corporate identity with commercial and cultural goodwill[4].

LEGAL PERSONALITY AND GOODWILL

Goodwill generally is an intangible asset in relation to the acquisition of a company or business by another. Goodwill is an essential asset of any enterprise because the core essence of its existence is embedded into it. The spectators and supporters of a sports organization or federation are to a great extent its customers, as their passion for their favorite sports team/event makes them follow with unquestionable enthusiasm. Asides the proprietary interest in goodwill, there are also personality interests. Personality rights are not limited to natural persons, as juristic persons like companies also have personality rights like reputation and identity.

Goodwill as well as reputation is intricately related to identity. Identity entails a wide range of things including specific products of an enterprise and the pattern in which it is packaged. In relation to sports federation as an enterprise, the “product” is the sports events and its identity is echoed in the tournaments, events or matches which uniquely differentiates it from other sports federations or bodies.

For instance, when one thinks of the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA)World Cup, it automatically gives you an image of the FIFA world cup trophy (18carat gold with bands of malachite on its base)[5], the blue FIFA flag with the organization logo in the middle, the FIFA anthem, the grand opening of the ceremony, the idea of it being a football game amongst the member countries, the recognitions and awards, and so on. These are essential characteristics of the identity of FIFA, and same can be said for other sports federations and tournaments they represent. It is these identifications that make it easy for a football fan to differentiate a premier league game from the German Bundes liga.

The identity right of FIFA in the above is breached where another person uses these distinct features which are primarily attributable to the Association for commercial gains without authorization. The core element of this breach is that the use was for a commercial purpose which is solely aimed at promoting a product or service to attract customers. The unlawfulness in this case is mainly vested in the violation of the right to freedom of association and the commercial exploitation of the individual or company.[6]

PROTECTION

Sporting International organizations in most cases explore various avenues to protect their IPRs. For example, the Olympic Charter in Article 7[7] contains provisions which provide strict safeguard for these IPRs. It provides among others that, “The International Organizing Committee (IOC) is the owner of all rights in the Olympic Games and Olympic properties described in this Rule, which rights have the potential to generate revenues for such purposes.

It is in the best interests of the Olympic Movement and its constituents which benefit from such revenues that all such rights and Olympic properties be afforded the greatest possible protection by all concerned and that the use thereof be approved by the IOC”. This point is further buttressed by paragraph 2 of Article 7 of the same Olympic Charter, which provided that “The Olympic Games are the exclusive property of the IOC which owns all rights and data relating thereto, in particular, and without limitation, all rights relating to their organization, exploitation, broadcasting, recording, representation, reproduction, access and dissemination in any form and by any means or mechanism whatsoever, whether now existing or developed in the future”[8]

This provisions show that the IOC have taken necessary steps to protect their brand. This protection goes beyond protecting the basic ‘properties’, but also the cultural goodwill and the commercial viability of the organization. In practice, along with the Olympic Charter, the IOC would need to have legislations passed by host cities to prevent ambush marketing. Host cities are also obligated to implement ‘brand protection programs’[9].

An instructive case study for this is the series of Intellectual Property cases that both FIFA and the Local Organizing Committee (LOC) of the 2010 FIFA World Cup had to battle against in South Africa, a decade ago. About 450 cases where filed against said offenders of these IPRs[10]. FIFA and the LOC’s campaign for protection of IPRs is probably one of the biggest in Sports history, as an extensive list of trademark registrations was released which demonstrated the paramount importance Sports organizations place on protecting their brands in terms of organization, staging and commercialization.

On the issue of FIFA and World Cups, in preparation for the 2014 World Cup, FIFA had 13,000 trademarks registered worldwide, 1160 of them registered for the World Cup and 400 occurred after the passage of the World Cup Law in Brazil, which was a law passed to prevent this ambush marketing[11]. This protection goes beyond, sports organizations or committee, and includes franchises who can file trademark applications for team names, logos and mascots.

Individual athletes also feel the need to create their own brands, gain endorsements and gain financially from trademarking names, initials, catch phrases or celebrations. In football and basketball, these are known as ‘image rights’, which allows a player employed with an organization to also gain value from the use of their images that is unconnected to their employer’s brand.

LANDMARK CASES OF TRADEMARK IN SPORTS

BARCELONA FC TRADEMARK CASE

In April 2013, Barcelona Football club (Barcelona) applied for the registration as a community (EU) Trade Mark of the silhouette of its crest in relation to a range of goods such as paper goods, stationery, clothing, footwear, headgear and even some sports activities. The Office for Harmonization in International Markets (OHIM) now known as the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), which is the body responsible for the registration of community trademarks, rejected the application on the grounds that the mark lacked distinctiveness, and therefore did not meet the basic requirement for registration. Barcelona appealed until it got to the EU General Court, where they also dismissed the appeal and ruled that:

- The crest silhouette is not capable of attracting the attention of consumers as a sign indicating the origin of the goods/services carrying that mark.

- The silhouette of a crest does not differentiate itself much from the basic shapes generally used in various commercial sectors as a decorative element.

- Therefore, the crest silhouette does not possess the inherent distinctive character[12]

WASHINGTON REDSKINS TRADEMARK CASE

There has been a legal fight which has persisted for about twenty years over the use of the Redskins team name by the Washington Redskins American Football club. The court in a ruling ordered the United States Federal Trademark and Patent Office to cancel several trademark registrations held by the club in respect of this name, on the ground that the name ‘Redskins’ may be reproachful to Native Americans, who have objected to the name for decades, while also citing dictionary entries stating that the name is considered to be offensive.

However, the present ruling does not prevent the club from using the name although the legal implication is that the name would no longer enjoy the full legal protection attributable to a federally registered trademark.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IN THE NIGERIA SPORTS SECTOR

Speaking particularly about the branches of Intellectual Property in Nigeria, we shall begin the discussion with Patents. Patents can be defined as the legal rights vested on inventors of new and useful products and processes, the right to exclude all others from commercially exploiting the invention. It is a right that rewards, ingenuity of thought. It ensures the author of the invention is afforded legal recognition and protection.

Once a patent has been registered in Nigeria and indeed around the world, it prevents those not afforded the rights from exploiting the use of that invention for commercial purposes. Patent protects the authors time, effort and resources used in producing a new invention. The author or patentee then holds the patent to such invention for the next twenty years (Section 7(2) of the Patents and Designs Act)[13]

In Nigeria today, the Sports industry, is still lacking behind the rest of the world in terms of industrialization and technological development. Instead we continue to reap the reward of the invention of others. One can confidently speak on and say that patent is the least utilized IPR in Nigeria. It is also key to state that, Sports people and inventors should not be deterred from being creative. The resources or platform may not be there, but one can never truly know, when his invention is the next best thing.

Copyright is another branch of IPR that seems to not exist in the Nigeria Sports industry. This branch of IPR is not only infringed on, but one might argue it is abused in Nigeria. This is because local markets are field with all sorts of fake jersey’s, scarfs, cups, slippers, boots etc. Essentially copyright is a right which protects the expression of an idea in a definite form and gives rights to the creator or owner the right to sell, produce, reproduce that expression of idea for their commercial benefits. This could be by themselves or another via through a testamentary deposition or grant of license.

The areas of sports where copyright abounds are the merchandise, Television and media rights literature contained in match day programs sold to fans, ticket sales, the software of computer and online games. In Nigeria most of the aforementioned being copied without permission. This also seems to discourage creativity as inventors do not see the means to commercialize their ideas, the protection afforded to them or the penalties for infringement are not stiff enough to encourage inventors.

Another branch of IPRs are Trademark. This along with copyrights are the most popular IPRS. Trademarks has its rights embedded in the very things we see everywhere when it comes to Sports. From logos, team names, league names, sporting goods, broadcasting and apparel. It is essentially anything that gives a brand an identity, such as symbols, crests, logos, catch phrases or anything that distinguishes the products (goods/services) of one business to another.

Trademarks are important as they allow supporters recognize easily the brand they are associated with. Naturally, trademarking would lead to good commercial output. For example, seeing the Nike tick or Puma jaguar would tell one that such product is that of Nike or Puma and they guarantee quality. Various forms of trademarking exist which include registering of nicknames by sports celebrities, catch-phrases, mascots.

It is clear that in Nigeria we are behind most of the world in Intellectual Property rights. The need to develop commercially potent brands that would compete transnationally, is at an all-time high. A major issue with the lack of protection or platform for inventors to develop in Nigeria is the fact that, Nigerian Sport is generally managed and controlled by the government. With that, it is difficult to allow businesses in the industry genuinely grow. At the end of the day, no one wants his/her efforts to be wasted without gains, and this extends to possible investors and stakeholders in the sport industry

The U.S Chamber International IP Index 2021[14], Nigeria ranks 47 of 50 countries in the assessment of economies whose intellectual property systems provide a reliable basis for investment in the innovation and creativity lifecycle[15]. This is a damning report, because it proves most of the aforementioned faults of the legal framework for IPRs in Nigeria. It is a challenging environment for the prosperity of goods and involves a high right of physical counterfeiting and online piracy remains high and public awareness of the value of IP remains low.

Just like in most Common Law jurisdictions, in Nigeria there are statutory protection for regular trademark, and the doctrine of passing off is also applicable. Laws and regulations established for the protection and administration of intellectual property rights include: the Copyright Act[16] , the Patents and Designs Act[17], the Trademarks Act[18], and so on.

The courts have not interpreted the provisions of the Nigerian Trademark Act to include marks from the sporting industry, and this may be likened to the fact that the sports jurisprudence in Nigeria is not as developed as it is in other jurisdictions like Europe and the United States of America. Nevertheless, it merely provides enough general covers that sport brands can explore in order to fully relish the benefits attached to IPRs for stakeholders. In the Nigerian sporting sector, the provisions of the Trademark Act and the Common Law doctrine of passing off must be fully utilized, as they are still vastly underutilized.

It is highly recommended that organizers of sports events should always protect their event marks by adopting the provisions of the Trademark Act which is similar to the provisions of the UK Trademark Act.[19]It is also suggested that every state with a sporting presence should enact a Law that would provide a mirrored protection available in the Federal Act enacted by the National Assembly.

For instance, the Nigerian Premier Football League (NPFL) can have an Act titled ‘The Nigerian Premier League Event Mark and Related Rights Act’ to be adopted by the various state governments. This would serve as the principal protection for all the marks associated with the NPFL throughout the Federation while the Trademark Act serves as secondary or ancillary protection for the football league.[20]

The importance of a proper shield of sports events marks in Nigeria cannot be overemphasized, as it would allow owners to exclusively exploit their marks for economic and financial gains. This can serve as a booster to the confidence of prospective sponsors and business partners, as it gives a sense of security for their investments.

CONCLUSION

With the rising enthusiasm and passion of individuals in the sporting sector, it will be highly disappointing if the full potentials of intellectual property rights in sports activities are not utilized to the maximum. In a bid to achieve this and protect the rights of stakeholders in this sector, it becomes pertinent that professional sport clubs and sport event organizers within Nigeria maintain the global standard.

In addition, the Legislative and Judicial bodies in Nigeria, are advised to amend and adjust our laws to toe the line of international sporting communities while considering our local circumstances, as the legislature governing intellectual property and by extension sports, are somewhat anachronistic.

The judiciary also, do not provide a hasty and less adversarial means of dispute resolution mechanism, hence, more people involved in sports should seek resources in arbitration, and make more use of avenues like the Lagos Court of Arbitration. All these measures would be to the national benefit as the economic and cultural benefits of hosting sporting events in a city or a country are always astronomical.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

STATUTES

Cap C28, Laws of the Federation, 2004

Cap P2, Laws of the Federation, 2004

Cap T13, Laws of the Federation, 2004

- 1 (1) of the UK Trademark Act, 1994

Article 7 of the Olympic Charter

Article 7, Paragraph 2 Olympic Charter

CASES

General Court of the European Union Press Release No 144/15, Luxembourg, 10 December 2015, Judgment in Fútbol Club Barcelona v OHIM, Case T-615/14.

Victoria Park Racing and Recreation Grounds Co Ltd v Taylor [1937] 58 CLR 479

Wells v Atoll Media (Pty) Ltd [2010] 4 All SA 548 (WCC).

ONLINE SOUCRES

Allen Kim (2020) Giannis Antetokounmpo signs largest deal in NBA history with Milwaukee Bucks https://edition.cnn.com/2020/12/15/us/giannis-antetokounmpo-contract-spt-trnd/index.html

Blackshaw I.S. (2017) IP and Sport. In: International Sports Law: An Introductory Guide. Short Studies in International Law. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. https://doi-org.gcu.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-198-2_5

FIFA.com https://www.fifa.com/who-we-are/news/the-fifa-world-cuptm-trophy-517161 Accessed 4th Jan 2021

George Ramsey (2021) Barcelona denies responsibility for leak after report reveals Lionel Messi’s record $672 million contract https://edition.cnn.com/2021/02/01/football/lionel-messi-barcelona-contract-spt-intl/index.html

BOOKS

Owen Dean “Sport as a Brand and its Legal Protection in South Africa”, ‘Global Sports Law and Taxation Reports’, March 2012 pp 41

Ugochukwu Johnson Amadi (2017); Intellectual Property Rights in Sports: African Sports Law and Business Bulletin

[1] George Ramsey (2021) Barcelona denies responsibility for leak after report reveals Lionel Messi’s record $672 million contract https://edition.cnn.com/2021/02/01/football/lionel-messi-barcelona-contract-spt-intl/index.html

[2] Blackshaw I.S. (2017) IP and Sport. In: International Sports Law: An Introductory Guide. Short Studies in International Law. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. https://doi-org.gcu.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-198-2_5

[3] Victoria Park Racing and Recreation Grounds Co Ltd v Taylor [1937] 58 CLR 479

[4] Blackshaw I.S. (2017) IP and Sport. In: International Sports Law: An Introductory Guide. Short Studies in International Law. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. https://doi-org.gcu.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-198-2_5

[5] FIFA.com https://www.fifa.com/who-we-are/news/the-fifa-world-cuptm-trophy-517161 Accessed 4th Jan 2021

[6] Wells v Atoll Media (Pty) Ltd [2010] 4 All SA 548 (WCC).

[7] Article 7 of the Olympic Charter

[8] Paragraph 2, Article 7 Olympic Charter

[9] Blackshaw I.S. (2017) IP and Sport. In: International Sports Law: An Introductory Guide. Short Studies in International Law. T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague. https://doi-org.gcu.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-198-2_5

[10] Owen Dean “Sport as a Brand and its Legal Protection in South Africa”, ‘Global Sports Law

and Taxation Reports’, March 2012

[11] Ibid 11

[12] See General Court of the European Union Press Release No 144/15, Luxembourg, 10 December

2015, Judgment in Fútbol Club Barcelona v OHIM, Case T-615/14.

[13]

[14] Global Investment Journal: U.S Chamber International IP Index https://www.theglobalipcenter.com/report/ipindex2021/

[15] Supra n14

[16] Cap C28, Laws of the Federation, 2004

[17] Cap P2, Laws of the Federation, 2004

[18] Cap T13, Laws of the Federation, 2004

[19] See S. 1 (1) of the UK Trademark Act, 1994

[20] Ugochukwu Johnson Amadi (2017); Intellectual Property Rights in Sports: African Sports Law and Business Bulletin

Written by: TUALE CHARLES AJUYAH and NNADI, EZINNE TOCHUKWU

Written by: TUALE CHARLES AJUYAH and NNADI, EZINNE TOCHUKWU

Tuale and Ezinne are Associate at Omaplex Law Firm.

Tuale, is a sports and entertainment lawyer who represents a wide variety of Nigerian and international clients including television broadcasters, Sport and Entertainment personalities, media companies, sports governing bodies, global brands and buddings musicians.

While Ezinne is a member of the Firm’s Dispute Resolution Team with a focus on intricate Civil Litigation. She has an outstanding experience in contract and business disputes. She has represented major debtors and creditors in high-profile Debt Recovery proceedings.

by Legalnaija | May 3, 2021 | Uncategorized

The Central Planning Committee (CPC) for the eagerly awaited Nigerian Bar Association Section on Public Interest and Development Law (NBA-SPIDEL) Annual Conference has invited exhibitors to add more value to the conference by providing services to conferees.

A statement today by the Media & Publicity Sub-committee said: “We therefore write to invite you to showcase your Company during the conference through exhibition and screen adverts on montage during the conference which will garner over 2,000 participants.” (more…)

by Legalnaija | May 2, 2021 | Uncategorized

You can now order law books and resources on the Legalnaija website.

Some of these books include;

International Arbitration Law & Practice: The Practitioners Perspective, edited by Tolu Aderemi of the firm Perchstone & Graeys https://t.co/D5lxlqe1uR

International Arbitration Law & Practice: The Practitioners Perspective, edited by Tolu Aderemi of the firm Perchstone & Graeys https://t.co/D5lxlqe1uR

Social Media For Lawyers by Adedunmade Onibokun https://t.co/CM9tabT4AX

Social Media For Lawyers by Adedunmade Onibokun https://t.co/CM9tabT4AX

Legal Rights And Obligations Under Nigerian Laws Ebook https://t.co/mWdxjN5Vhr

Legal Rights And Obligations Under Nigerian Laws Ebook https://t.co/mWdxjN5Vhr

For enquiries and book placement opportunities for Authors & publishers, kindly send a mail to hello@legalnaija.com

by Legalnaija | Apr 29, 2021 | Uncategorized

#NBASPIDEL2021: CJN, Governors Makinde, Akeredolu SAN, And Other Special Guests Confirm Attendance

Dear Branch Chairman

It is my pleasure to, on behalf of the NBA Section on Public Interest and Development Law (NBA-SPIDEL), write you and solicit your participation, that of your fellow executives and members of your esteemed Branch in the forthcoming SPIDEL Annual Conference taking place in Ibadan between 23rd and 26th May, 2021.

The theme of the Conference is “The Role of Public Interest in Governance in Nigeria.” Some of the sub-themes are as follows: The Imperatives of Public Interest in Governance in Nigeria; Internal Security: A Prerequisite for National Development; Legality and Efficacy of Public Inquiry Panels by State Governments; Legality and Efficacy of Regional Vigilantes; When the State Truly Defends: assessing the role of the Office the Public Defender Lagos State; Anti-Corruption Model: Assets Declaration and Public Access; Showcase Session for NBA: Public Interest Litigation Committee – Broadening the strategy for NBA’s Intervention in Public Interest Lawyering, and some many others.

The Speakers that have confirmed their attendance and participation include: The Chief Justice of Nigeria, Hon Justice Tanko Muhammad; His Excellency, Engr. Seyi Makinde, Governor of Oyo State; Governor of Ondo State, Rotimi Akeredolu SAN;

Professor Pat Utomi; Professor Festus Emeri SAN; ICPC Chairman, Professor Bolaji Owasanoye SAN; Oyo State Attorney General, Prof. Oyelowo Oyewo SAN; Prof. Chidi Odinkalu; Ogun State Attorney General, Mr. Gbolahan Adeniran; NBA Board of Trustees Chairman, Dr. Olisa Agbakoba SAN; Mr. Austin Alegeh SAN; Mr. Paul Usoro SAN; Dr. Babatunde Ajibade SAN; Chief Bolaji Ayorinde SAN; Mr. Kemi Pinheiro SAN; Mr. Lawal Pedro SAN; Mr Muiz Banire SAN, Mr J.S. Okukpeta SAN, Mr Afam Osigwe SAN, AG of Lagos State, Mr Seun Abimbola SAN, Ms Hafsat Abiola, leading human rights lawyers such as Mr. Femi Falana SAN; Chief Mike Ozekhome SAN; Mr. Jiti Ogunye, and Mr. Ebun Adegboruwa SAN. Others are Aisha Yesufu, Liborous Oshoma, Anthony Ojukwu (Executive Secretary, National Human Rights Commission), and Mr. Opunabo Inko-Fariah. The Legislature is also well represented as follows: Senator Enyinnaya Abaribe, Senator Ike Ekweremadu, Senator Dino Melaye, Rt. Hon. Adebo Ogundoyin (Oyo State House of Assembly Speaker) and his Lagos counterpart, Rt. Hon. Mudasiru Obasa.

Other invited Speakers are Nigeria’s Vice President, Mr. Yemi Osinbajo SAN; Hon Justice Eko Ejembi of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, Speaker of HOR, Mr Femi Gbajabiamila, President of the Senate, Senator Ahmed Lawan Bauchi State Governor, Dr. Bala Mohammed; Ebonyi State Governor, Engr. Dave Umahi; Senator Ibrahim Shekarau and Senator Shehu Sani. The Chief Host is the NBA President, Mr. Olumide Akpata while NBA-SPIDEL Chairman, Prof. Paul Ananaba SAN is the Host.

We have just come back from Ibadan. The ancient city is already wearing a new and beautiful look as a result of the tremendous effort being put by the current administration to deliver the dividends of democracy to the people. Therefore, we are poised to have a beautiful conference in an atmosphere of peace and tranquility. In fact, Governor Makinde has been emphatic in assuring delegates thus: “We will ensure that you have a very good experience.” The Conference venue is the popular Jogor Event Centre which can sit over 3000 guests at once. We will ensure adequate social distancing in strict compliance with Covid-19 protocols. We have also secured top class hotels in the city for our delegates. For those in love with amala, gbegiri, ewedu, ogufe and orisirisi (variety) meats, be rest assured that arrangements are on top gear to satisfy your appetite.

<span;>The Governor of Oyo State, His Excellency Seyi Makinde has also agreed to declare open the conference on 24th May, 2021. To register, please click on this link http://nbaspidel.ng/nba-spidel-conference/.

<span;>To make your stay enjoyable and comfortable in Ibadan, we are partnering with NACO LOGISTICS (08069206814) to facilitate lodging arrangements for delegates. Members and conferees are encouraged to make early hotel reservations. Our partner hotels are as follows:

<span;>1. Kakanfo Inn and Conference Center

<span;>Address: 1 Nihinlola street, off Ring Road, Ibadan.

<span;>Regular room: 35,300

<span;>Signature-48,900

<span;>Suite: 53,000

<span;>Flat rate: 20,000 with breakfast (more than 50% discount)

<span;>No of rooms: 80

<span;>2. Mahogany Hotel and Suite

<span;>Address: 4 Remi Alabi street, by all saints church, Jericho Ibadan

<span;>Deluxe Room: 36,000

<span;>Royal Room: 55,000

<span;>Flat rate: N33,000 with buffet breakfast (40% discount)

<span;>No of rooms: 30

<span;>3. Queen’sway Resort

<span;>Address: 21 Adekoyejo Avenue, Iyaganku GRA, Ibadan.

<span;>Queens Executive: 12,000

<span;>Queens platinum: 16,500

<span;>Queens palace: 18,000

<span;>Queens Blue: 20,000

<span;>*Flat rate: 13,000.* With break fast

<span;>*12,000* without breakfast

<span;>*No of rooms*: 30

<span;>4. Grand Serene Hotel

<span;>Address: Iyaganku, off Ring road Ibadan

<span;>Executive Room: 14,000

<span;>Superior Room: 15,500

<span;>Deluxe suite:20,000

<span;>*Flat Rate: 13,000*(30% discount)

<span;> *No of rooms*: 30

<span;>5. Fawzy Hotel

<span;>Block 7 Adewumi layout, off Akinyemi way, Ring road, ibadan

<span;>Deluxe Room:27,500

<span;> *Discounted Rate: 22,000* with breakfast (20% discount)

<span;>*No of rooms:* 15

<span;>6. Bayse Hotel one place

<span;>Address: plot 14/16 Akinola Maja street opp 3sc/shooting stars FC office, Jericho

<span;>Executive Room: 18,000

<span;>Super Deluxe: 25,000

<span;>*Flat rate*:15,000 without breakfast(25% )

<span;>*No of rooms*: 20

<span;>(7) Joybam Hotel

<span;> Address: off ring road, Osasami Behind liberty stadium complex, Oke Ado Ibadan

<span;>Super royal: 10,000

<span;> *Discounted rate* 9,000 without breakfast

<span;>Executive: 14,000

<span;>*No of rooms: 26*

<span;> (8) Academy Suite

<span;>Address: Osasami Road, near Ibadan Central Hospital

<span;>Standard Deluxe Room: 14,000

<span;>Super deluxe Room

<span;> *Flat rate: 12,000* without breakfast(25% discounted rate)

<span;>**No of room:* 40

<span;>(9) Best Western plus hotel

<span;>Address: 25, Jibowu crescent, GRA Ibadan

<span;>Deluxe Room: 50,000

<span;>Discounted rate: 42,000 with buffet breakfast(18%discount)

<span;>*No of rooms* 40

<span;>(10) Classic Hotel

<span;>*Address:*

<span;>MKO Abiola Way, Ring Road, Ibadan

<span;>Deluxe room: 8,000

<span;>No discount:

<span;> *No of rooms:* 13

<span;>(11) Capital Inn Plus

<span;>*Address:* 8-10 7th Avenue, Oluyole Estate, Ring road

<span;>Diplomatic room: 30,000

<span;>Discounted rate: 22,000 without breakfast.

<span;>25,000 with buffet breakfast(20%discount)

<span;>*No of rooms*

<span;>(12) La Maison Hotel

<span;> *Address:* 23 Jibowu Road, Iyaganku, GRA, Ibadan

<span;>Premium room: 17,500

<span;>Discounted rate: 17,000

<span;> *No of room* 20

<span;>(13) Ashosh Hotel

<span;>*Address:* Ashosh 1st Avenue Iyaganku GRA

<span;>Standard room: 15,000

<span;>Executive room: 21,500

<span;> *Flat rate:* 14,000 without break fast

<span;>(30% discount)

<span;>*No of room* 10

<span;>(14) Rendezvous Hotel

<span;>Address: off Foodco Supermarket, Jericho, Ibadan

<span;>Standard Room: 15,000

<span;>Discounted rate: 14,000

<span;>Deluxe room: 25,000

<span;>Classic room: 27,000

<span;>Executive Room: 30,000

<span;> *Flat rate: 23,000* without breakfast

<span;>*No of room* : 30

<span;>(15) Golden Tulip Hotel

<span;>*Address:* Qtr 781 GRA Jericho Ibadan

<span;>Deluxe room: 48,500

<span;>Executive room: 89,500 with buffet breakfast.

<span;>No discount

<span;> *No of rooms* 40

<span;>NOTE:

<span;>Reservations should be made through NACO LOGISTICS LTD(08069206814) Reservations cannot be confirmed unless a deposit of the first night is made. All payments must be made at least two weeks before the conference which commences on the 23rd of May, 2021. All payments only for the first night should be made to NACO LOGISTICS with the account details below: 0422942749 (GTB), NACO LOGISTICS LTD.

<span;>Contact: LOC/SPIDEL PUBLICITY SUB-COMMITTEE

<span;>If you desire to be a member of SPIDEL, here below are information for your membership.

<span;>Payment of the Section’s Annual Dues

<span;>a. Section Membership above 10years post call – N10,000

<span;>b. Section Membership from 6-10years – N5,000

<span;>c. Section Membership from 0-5years post call – N3,000

<span;>METHOD OF PAYMENT

<span;>Pay all Section dues into the bank account listed below

<span;>BANK: Access Bank PLC;

<span;>ACCOUNT NUMBER: 0775676671

<span;>ACCOUNT NAME: Nigerian Bar Association (SPIDEL ACCOUNT)

<span;>Evidence of payment should be sent to: Edidiong Peter, NBA Programme Officer, Section on Public Interest and Development Law via E-mail: nbaspidel@nigerianbar.org.ng Peter.Edidiong@nigerianbar.org.ng. Tel: 08003331111. Prospective exhibitors are also invited to showcase their products. Please contact Mr. Edidiong Peter (08003331111) or the Local Orgaising Committee (Mr. Olayinka Esan, 08033261598).

<span;>Gentlemen, Ibadan is ready for us. I hereby invite you, your fellow executives and the entire membership of your branch to come to Ibadan to experience the beautiful scenery and the tourist attractions of this ancient city. Trust me, it shall be a memorable experience for everyone who honours this invitation and participates in the conference.

Your Obedient Servant,

Onyekachi Ubani Esq. (MOU)

Chairman, Conference Planning Committee

NBA-SPIDEL Annual Conference ubangwa@gmail.com

by Legalnaija | Apr 27, 2021 | Uncategorized

Oyo State Governor, Engr. ‘Seyi Makinde has promised that the state will host a memorable annual conference of the Nigerian Bar Association Section on Public Interest and Development Law (NBA-SPIDEL) in Ibadan from May 23 to 26.

Speaking while receiving a delegation of NBA-SPIDEL at Government House, Agodi, Ibadan, Makinde assured that the state would also provide a safe environment for the delegates.

He said: “I am glad that you are bringing the conference here because that is what we want to see. We want people to come around and experience what we are trying to do here. We will support you.”

According to Makinde, “We will provide a safe and secure environment for the annual conference. We will ensure that you have a very good experience.”

The Oyo State Governor, who promised to personally declare open the annual conference, also observed that the conference would boost the state’s economy, noting that “some of the money to be spent by the 2000 delegates will trickle down to the business sector.”

Noting that NBA-SPIDEL has a special place in his heart, Makinde said: “The Section on Public Interest is something that is very interesting to us because I always tell people that this government was put in place by the people themselves.

“We did not come in through any godfather. We did not come in because we had federal might. We did not even have local might when we were about to get elected. So, we can only run a government that is sensitive to the yearnings of our people. If we are hosting a conference of Nigeria Bar Association Section on Public Interest and Development Law, we think this is an appropriate place for that to happen.”

According to a statement by a member of the delegation and Head of Media & Publicity for the conference, Mr. Emeka Nwadioke, Makinde expressed worry at the rising unemployment in the country as well as the over-dependence on the Federal Government for allocations, urging lawyers to “let your voices be heard” in resolving the crises of federalism and nation-building.

He said: “My Commissioner for Finance is in Abuja now for FAAC. If we don’t have it, the whole place will probably collapse. But why should that be? If it is a federation, why are we all running to Abuja every month to look for federal allocation? Those are some of the challenges that I know when legal minds come together, they can assist the country on. You can weigh in and let your voices be heard.”

In his welcome address, the Oyo State Attorney-General & Commissioner for Justice, Prof. Oyelowo Oyewo (SAN) said that the annual conference “could not have come at a better time,” adding that the state is noted as a pacesetter which hosts the oldest Ministry of Justice in the country.

The NBA-SPIDEL Chairman, Prof. Paul Ananaba (SAN) in his address said that about 2,000 delegates would attend the annual conference tagged “Ibadan 2021” to brainstorm on issues that border on public interest and development.

He noted the developmental strides of the administration, adding that the fact that a majority of the Cabinet members are lawyers must have contributed positively to Makinde’s success. Ananaba also commended the government for displaying public interest by relocating displaced traders instead of abandoning them.

He stated that the annual conference would hold from May 23 to 26 this year, adding that a surfeit of leading human rights and other speakers have committed to attend the conference to tackle the theme, “The role of public interest in governance in Nigeria.”

The NBA-SPIDEL delegation included former NBA General Secretary and Chairman of Oyo State Independent Electoral Commission (OSIEC), Mr. Abiola Olagunju (SAN); human rights activist and Chairman of the Conference Planning Committee (CPC), Mr. Monday Ubani, and NBA Ibadan Branch Chairman, Mr. Olayinka Esan. The delegation was received by Governor Makinde alongside the Secretary to the State Government, Mrs. Olubanwo Adeosun; Chief of Staff, Chief Oyebisi Ilaka and five commissioners including Prof. Oyewo; Mr. Olasunkanmi Olaleye (Education, Science & Technology); Mr. Adeniyi Farinto (Budget & Planning); Mr. Seun Ashamu (Energy) and Mr. Rahman AbdulRaheem (Lands) as well as the Director General of Due Process, Tara Adefowopo.

Written by: TUALE CHARLES AJUYAH and NNADI, EZINNE TOCHUKWU

Written by: TUALE CHARLES AJUYAH and NNADI, EZINNE TOCHUKWU

International Arbitration Law & Practice: The Practitioners Perspective, edited by Tolu Aderemi of the firm Perchstone & Graeys

International Arbitration Law & Practice: The Practitioners Perspective, edited by Tolu Aderemi of the firm Perchstone & Graeys  Social Media For Lawyers by Adedunmade Onibokun

Social Media For Lawyers by Adedunmade Onibokun  Legal Rights And Obligations Under Nigerian Laws Ebook

Legal Rights And Obligations Under Nigerian Laws Ebook