Flawed and

insignificant research propagated in advertisements amount to misleading

advertisements. In the same vein, where an advertisement, is based on flawed

and insignificant research or are contradicted by prevailing authority or

research section 43(a) of the Lanham Act

refers to such advertisements as false. In Alpo

Pet Foods v. Ralston Purina Co.[ii]

the claimant brought a claim of false advertising against Purina whose

adverts that its dog food was beneficial for dogs with canine hips dysplasia

demonstrating that the claims was supported by test results conducted by Purina

which showed that the methods used to conduct the tests were inadequate and the

results could therefore not support Purina’s claims.

insignificant research propagated in advertisements amount to misleading

advertisements. In the same vein, where an advertisement, is based on flawed

and insignificant research or are contradicted by prevailing authority or

research section 43(a) of the Lanham Act

refers to such advertisements as false. In Alpo

Pet Foods v. Ralston Purina Co.[ii]

the claimant brought a claim of false advertising against Purina whose

adverts that its dog food was beneficial for dogs with canine hips dysplasia

demonstrating that the claims was supported by test results conducted by Purina

which showed that the methods used to conduct the tests were inadequate and the

results could therefore not support Purina’s claims.

The case involving Purina

is a common re-occurence in Nigeria specifically the Uyo Metropolis in Akwa

Ibom State. Adverts that make claims that have been rebutted by prevailing

scientific authority can be sighted within the city. (Discovery Park ” Eat a Plate of Isi-Ewu or Nkwobi daily its

is good for your health) such adverts pose health risks for vulnerable

consumers especially the elderly. They lure consumers to make decisions

(purchase decisions) that are based on such claims that have been unseated by

superior evidence like the opinion of Ballentyne[iii] which

states that goat meat though healthy should not be consumed daily. Another

popular case of advertisements that makes flawed research claims are the likes

of Iguedo Goko cleanser, Dazzle Shea

butter. These adverts claim to cure all kinds of ailments and make

diagnosis based external symptoms of a person example rashes, heat flushes,

painful urination etcetera which are not enough base medical diagnosis. The

adverse impacts of these advertisements have led consumers into going against

established medical precaution s and placing their confidence in these products

can eventually worsen their condition and send them to intensive care.

is a common re-occurence in Nigeria specifically the Uyo Metropolis in Akwa

Ibom State. Adverts that make claims that have been rebutted by prevailing

scientific authority can be sighted within the city. (Discovery Park ” Eat a Plate of Isi-Ewu or Nkwobi daily its

is good for your health) such adverts pose health risks for vulnerable

consumers especially the elderly. They lure consumers to make decisions

(purchase decisions) that are based on such claims that have been unseated by

superior evidence like the opinion of Ballentyne[iii] which

states that goat meat though healthy should not be consumed daily. Another

popular case of advertisements that makes flawed research claims are the likes

of Iguedo Goko cleanser, Dazzle Shea

butter. These adverts claim to cure all kinds of ailments and make

diagnosis based external symptoms of a person example rashes, heat flushes,

painful urination etcetera which are not enough base medical diagnosis. The

adverse impacts of these advertisements have led consumers into going against

established medical precaution s and placing their confidence in these products

can eventually worsen their condition and send them to intensive care.

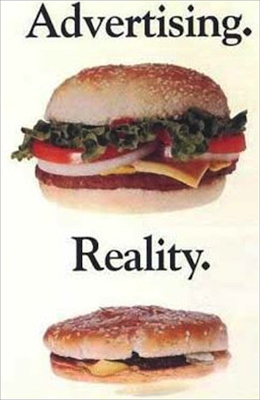

Trade marks

infringement also constitutes false advertisements as it is intended to mislead

and confuse consumers. In Edina Really

Inc. v. TheMLSOnline.com[iv]

the use of a key word in an advert amounted to trade mark infringement and

false advertisement as it was purported to mislead consumers. In Hamzik v. Zale Corps/Delware,[v]

the use of another’s trademark to trigger online advertisements (i.e to

generate traffic) was regarded as a clear cut case of false advertisement and

trademark infringement.[vi]

The case of Polariod Corp v Pzlora

Electronics Corp laid the test for such confusion. False labelling on

products constitutes false and misleading advertisements; it may take various

subtle ways like images that are suggestive, false production origin, false

nutritional value. The Pre-Packaged food (Labelling) Regulations 1995 and

Regulation 18 of The Nigerian Food Products (Advertisement) Regulations[vii]

prohibits false labeling. The Food and Drugs Act 1955 makes it an offence to

give any food exposed for sale a label that falsely describes the food or is

calculated to mislead as to its nature, substance, or quality. Quality was been

defined in the case of Aness v. Grivell[viii]

to mean the commercial quantity and not the commercial description. Quality

also includes nutritional or dietary value of the food and any label construed

to mislead the public on such grounds are misleading advertisements. In Kingston-upon-Thames Royal London Borough

Council v. F.W Woolworth and Co. Ltd,[ix]

the test of false labeling or advertisement as depends on whether a label

or advertisement falsely described food seems to depend on how an ordinary

individual would interpret the description in question. The publishing, giving

or display of such product is a strict liability offence without the element of

mens rea needed to secure a

conviction as decided in Kat v Diment.[x]

The NAFDAC Guidelines for Advertisements of Regulated Products in Nigeria[xi]

recognises the prevalence of herbal medicine amongst Nigerians. In a bid to

protect the consumer from misleading adverts or labeling of herbal medicines

states that such labels and advert shall include the caveat, “These claims have

not been evaluated by NAFDAC.”[xii]

This is not enough protection especially where most adverts by herbal medicine

dealers are aired on public address systems in the local languages and since

the caveat by NAFDAC only requires that it be stated in English language by

implication, it is this lacuna that herbal medicine advertisers exploit and

deceive consumers. Furthermore the NAFDAC regulation does not foresee the

protection of animals even though that is beyond the scope of this work. The

Medicines Act[xiii]

the United Kingdom counterpart of the NAFDAC Regulation takes a more holistic

definition which includes substances or articles manufactured sold or supplied

to be administered to human beings or animals for a medicinal purpose. The

Medicines Act prohibits the issuance of false advertisements relating to

medicinal products. It also states that an advertisement is false or misleading

only if it falsely describes the medicinal properties of the medicinal product

to which it relates.

infringement also constitutes false advertisements as it is intended to mislead

and confuse consumers. In Edina Really

Inc. v. TheMLSOnline.com[iv]

the use of a key word in an advert amounted to trade mark infringement and

false advertisement as it was purported to mislead consumers. In Hamzik v. Zale Corps/Delware,[v]

the use of another’s trademark to trigger online advertisements (i.e to

generate traffic) was regarded as a clear cut case of false advertisement and

trademark infringement.[vi]

The case of Polariod Corp v Pzlora

Electronics Corp laid the test for such confusion. False labelling on

products constitutes false and misleading advertisements; it may take various

subtle ways like images that are suggestive, false production origin, false

nutritional value. The Pre-Packaged food (Labelling) Regulations 1995 and

Regulation 18 of The Nigerian Food Products (Advertisement) Regulations[vii]

prohibits false labeling. The Food and Drugs Act 1955 makes it an offence to

give any food exposed for sale a label that falsely describes the food or is

calculated to mislead as to its nature, substance, or quality. Quality was been

defined in the case of Aness v. Grivell[viii]

to mean the commercial quantity and not the commercial description. Quality

also includes nutritional or dietary value of the food and any label construed

to mislead the public on such grounds are misleading advertisements. In Kingston-upon-Thames Royal London Borough

Council v. F.W Woolworth and Co. Ltd,[ix]

the test of false labeling or advertisement as depends on whether a label

or advertisement falsely described food seems to depend on how an ordinary

individual would interpret the description in question. The publishing, giving

or display of such product is a strict liability offence without the element of

mens rea needed to secure a

conviction as decided in Kat v Diment.[x]

The NAFDAC Guidelines for Advertisements of Regulated Products in Nigeria[xi]

recognises the prevalence of herbal medicine amongst Nigerians. In a bid to

protect the consumer from misleading adverts or labeling of herbal medicines

states that such labels and advert shall include the caveat, “These claims have

not been evaluated by NAFDAC.”[xii]

This is not enough protection especially where most adverts by herbal medicine

dealers are aired on public address systems in the local languages and since

the caveat by NAFDAC only requires that it be stated in English language by

implication, it is this lacuna that herbal medicine advertisers exploit and

deceive consumers. Furthermore the NAFDAC regulation does not foresee the

protection of animals even though that is beyond the scope of this work. The

Medicines Act[xiii]

the United Kingdom counterpart of the NAFDAC Regulation takes a more holistic

definition which includes substances or articles manufactured sold or supplied

to be administered to human beings or animals for a medicinal purpose. The

Medicines Act prohibits the issuance of false advertisements relating to

medicinal products. It also states that an advertisement is false or misleading

only if it falsely describes the medicinal properties of the medicinal product

to which it relates.

Advertisements on

weight loss product have also come under scrutiny for being false and

misleading. While some consumers do not live to tell the story, on a daily

basis vulnerable consumers are influenced by the idea of a perfect body sold by

the media to purchase quick weight loss products. In the Indian case of Smt Divya Wood v Ms Gurdeep Kaur Bhuhi,[xiv]

the court decided that a refund be made to a consumer who paid for a body care

programme that promised weight reduction. After payment and undergoing

treatment the plaintiff did not lose any weight. The apex consumer court said

“we entirely agree with this findings recorded by the fora below such

tempting advertisements, giving misleading statements with regard to the

alleged treatment, are increasing day-by-day and are required to be checked so

that persons may not be lured to pay large amounts in a hope that they can

reduce their weight by undergoing the so-called treatment.” In Jody Gorran v Atkins Nutritional Inc,[xv] the plaintiff Jody Gorran lured by the advert

Atkins Nutritional Inc. proceeded to begin their diet as advertised. Rather

than lose weight Jody Gorran gained high cholesterol levels, angina and some

other heart complications that needed emergency surgery to save his life. He

sued Atkins the courts however did not rule in his favour stating that the

Atkin’s diet book did not constitute advertisements. It appears the decision of

the court was based on the fact that safe and effective methods of weight loss

often involve a modification of behaviour, decreased calorie intake and

exercises. This is not particularly appealing as a result some consumers opt

for weight loss products that promise rapid weight loss with little or no

effort.[xvi]

Despite efforts to curb false and misleading adverts, they have continued to

grow in weight-loss advertisements, this is problematic because some vulnerable

consumers base their decision making on advertising, and advertisements with

false and misleading information pose threats to them. Furthermore, if the

entire field of ‘weight-loss’ advertisement is subject to wide-spread

deception, advertising will lose its role in the efficient allocation of

resources in a free-market economy. This is because other manufacturers end up

advertising the impossible in order to compete and the deceptive promotion of

quick and easy weight-loss solutions could potentially fuel unrealistic

consumer expectations.

weight loss product have also come under scrutiny for being false and

misleading. While some consumers do not live to tell the story, on a daily

basis vulnerable consumers are influenced by the idea of a perfect body sold by

the media to purchase quick weight loss products. In the Indian case of Smt Divya Wood v Ms Gurdeep Kaur Bhuhi,[xiv]

the court decided that a refund be made to a consumer who paid for a body care

programme that promised weight reduction. After payment and undergoing

treatment the plaintiff did not lose any weight. The apex consumer court said

“we entirely agree with this findings recorded by the fora below such

tempting advertisements, giving misleading statements with regard to the

alleged treatment, are increasing day-by-day and are required to be checked so

that persons may not be lured to pay large amounts in a hope that they can

reduce their weight by undergoing the so-called treatment.” In Jody Gorran v Atkins Nutritional Inc,[xv] the plaintiff Jody Gorran lured by the advert

Atkins Nutritional Inc. proceeded to begin their diet as advertised. Rather

than lose weight Jody Gorran gained high cholesterol levels, angina and some

other heart complications that needed emergency surgery to save his life. He

sued Atkins the courts however did not rule in his favour stating that the

Atkin’s diet book did not constitute advertisements. It appears the decision of

the court was based on the fact that safe and effective methods of weight loss

often involve a modification of behaviour, decreased calorie intake and

exercises. This is not particularly appealing as a result some consumers opt

for weight loss products that promise rapid weight loss with little or no

effort.[xvi]

Despite efforts to curb false and misleading adverts, they have continued to

grow in weight-loss advertisements, this is problematic because some vulnerable

consumers base their decision making on advertising, and advertisements with

false and misleading information pose threats to them. Furthermore, if the

entire field of ‘weight-loss’ advertisement is subject to wide-spread

deception, advertising will lose its role in the efficient allocation of

resources in a free-market economy. This is because other manufacturers end up

advertising the impossible in order to compete and the deceptive promotion of

quick and easy weight-loss solutions could potentially fuel unrealistic

consumer expectations.

Making false promises

in order to sell a product is another unfair and misleading advertising tool.

Promotional advertisements in general encourage the consumption of these

products in large quantities in avid to win the lucky reward. In the case of Bonn Nutrients Pvt. Ltd v Jagpal Singh[xvii]

a consumer brought a complaint that in order to promote a brand of bread

called “Bonn” the manufacturers announced through advertisements that

each packet will contain a scratch and win coupon. The consumer-complainant claimed

he bought several quantities of the product but every time he scratched the

coupon it read “try again”. The court ruled in his favour and stated

that the advertisements misled the general public and it had not made good on

the statements it made in its advertisements. Cases like “Bonn” exists

howbeit; the regulatory agency saddled with the responsibility is the Nigerian

Lottery Commission. They appears to be only concerned with ensuring that the

lucky prize exists and nothing more. It can be said conclusively that these

regulatory agencies do not provide protection for the consumer who might be

harmed by his efforts to win the coveted prize, however, the efforts include

excessive consumption of the product.

in order to sell a product is another unfair and misleading advertising tool.

Promotional advertisements in general encourage the consumption of these

products in large quantities in avid to win the lucky reward. In the case of Bonn Nutrients Pvt. Ltd v Jagpal Singh[xvii]

a consumer brought a complaint that in order to promote a brand of bread

called “Bonn” the manufacturers announced through advertisements that

each packet will contain a scratch and win coupon. The consumer-complainant claimed

he bought several quantities of the product but every time he scratched the

coupon it read “try again”. The court ruled in his favour and stated

that the advertisements misled the general public and it had not made good on

the statements it made in its advertisements. Cases like “Bonn” exists

howbeit; the regulatory agency saddled with the responsibility is the Nigerian

Lottery Commission. They appears to be only concerned with ensuring that the

lucky prize exists and nothing more. It can be said conclusively that these

regulatory agencies do not provide protection for the consumer who might be

harmed by his efforts to win the coveted prize, however, the efforts include

excessive consumption of the product.

END NOTES

[i] Akpan, Emaediong Ofonime is

currently undergoing postgraduate studies at the University of Uyo and majors

in Consumer Protection. She can be reached at akpanemaediongofonime@gmail.com.

currently undergoing postgraduate studies at the University of Uyo and majors

in Consumer Protection. She can be reached at akpanemaediongofonime@gmail.com.

[ii] 913 F.2d 958 (D.C. Cir. 1990)

[iii] D Ballentyne, www.supplementsource.co.ca

accessed 9th January 2017.

accessed 9th January 2017.

[iv] (2006) WL 737064. See also F.T.C v. Sili Neutralceutical 154

F.SUPP 2D 497. And Playboy Enterprises Inc.

v. Netscape Communication Corps 55 F. SUPP 2D 1070 (C.D CAL).

F.SUPP 2D 497. And Playboy Enterprises Inc.

v. Netscape Communication Corps 55 F. SUPP 2D 1070 (C.D CAL).

[v] NO3 : 06-CV-1300

[vi] The Trademark Act CAP T 13 LFN

2004 regulates the use of a trademark. Consequently, the use of a trademark

identical to that of COCACOLA by AJE[vi] to sell an identical

product ‘Big Cola’ amounts to only an infringement of trade mark because the

existing framework’s definition of false advertisement does not bring into its

purview trademarks infringement. Consumers were under the impression that it was

coca cola. One trader noted that she was mislead to purchase ‘Big Cola’ thinking it was Coca

cola, she lost customers who came to purchase coca cola because she sold ”Big Cola’ to consumer unknown to her

that it wasn’t Coca-Cola which the

customer requested.

2004 regulates the use of a trademark. Consequently, the use of a trademark

identical to that of COCACOLA by AJE[vi] to sell an identical

product ‘Big Cola’ amounts to only an infringement of trade mark because the

existing framework’s definition of false advertisement does not bring into its

purview trademarks infringement. Consumers were under the impression that it was

coca cola. One trader noted that she was mislead to purchase ‘Big Cola’ thinking it was Coca

cola, she lost customers who came to purchase coca cola because she sold ”Big Cola’ to consumer unknown to her

that it wasn’t Coca-Cola which the

customer requested.

[vii] 1994 NO.15. S.I 13 of 1996

[viii] (1915) 3KB 685, at p.691.

[ix] (1968) 1Q.B. 802.

[x] (1951) 1 K.B. 34.

[xi] NAFDAC

is empowered by the NAFDAC Act CapN1 LFN 2004 to regulate and control the

manufacture, exportation,

importation, and advertisement of medicines, cosmetic, medical devices, bottled

water and chemicals. The

Advertisement Control Division in the directorate of Registration and

Regulatory Affairs of NAFDAC.

is empowered by the NAFDAC Act CapN1 LFN 2004 to regulate and control the

manufacture, exportation,

importation, and advertisement of medicines, cosmetic, medical devices, bottled

water and chemicals. The

Advertisement Control Division in the directorate of Registration and

Regulatory Affairs of NAFDAC.

[xii]

Regulation 10

Regulation 10

[xiii] 1968

[xiv] (1989) L.P.A No. 646

[xv] No. 2004-CC-006591-MB(Fla. Palm Beach County

Ct.May 26,2004)

Ct.May 26,2004)

[xvi] J

Cawley et all, ‘The Effect of Advertising on Consumption: The Case of Over-the

Counter Wight Loss Products’ (2011)

University of Cornell Law Review

Cawley et all, ‘The Effect of Advertising on Consumption: The Case of Over-the

Counter Wight Loss Products’ (2011)

University of Cornell Law Review

[xvii] IV (2005) CPJ 108 NC.

Akpan, Emaediong Ofonime is

currently undergoing postgraduate studies at the University of Uyo and majors

in Consumer Protection. She can be reached at akpanemaediongofonime@gmail.com

currently undergoing postgraduate studies at the University of Uyo and majors

in Consumer Protection. She can be reached at akpanemaediongofonime@gmail.com

Photo Credit – Here